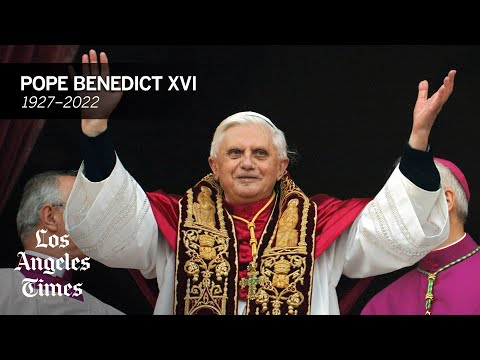

Former Pope Benedict XVI, conservative pontiff who was first in 600 years to resign, dies

Former Pope Benedict XVI, who will forever be remembered as the first pontiff in 600 years to resign from the job, dies at 95.

Benedict XVI, the former pope who spent years in the Vatican upholding conservative Catholic teaching but who upended centuries of tradition by resigning as pontiff, died Saturday, the Vatican announced. He was 95.

The German-born Benedict lived out his final years in a converted monastery at the Vatican, giving rise to the anomalous situation of two popes in one place, which later inspired the 2019 film “The Two Popes.” But his successor, Francis, accorded him great respect and never appeared fazed at having a possible rival in such close proximity.

Bookish and shy, Benedict withdrew to a life of study and prayer “hidden from the world” after announcing in February 2013 that he would step down from the throne of St. Peter. The shock decision — the first time a pope voluntarily abdicated in nearly 600 years — followed a decline in his health amid the strain of continued scandals within the Vatican and criticism from without.

He spent his eight-year papacy trying to turn back the rising tide of secularism in Europe, defending the church’s response to widespread allegations of clerical sexual abuse and, toward the end, dealing with the embarrassing leak of his private documents by his personal butler.

He also hewed unswervingly to strict Catholic orthodoxy, a theological absolutism he honed and enforced during his years as guardian of church doctrine under Pope John Paul II, with a zeal that earned him the nickname “God’s Rottweiler.”

He always seemed more comfortable in such a role, behind the scenes, rather than out in front of the adoring masses. Benedict’s diffident public manner contrasted starkly with the hearty, open-armed, people-loving style of both the pope who reigned before him, John Paul, and the one who came after, Francis.

Indeed, Benedict once compared his election as pope to having the guillotine fall on him, a prospect that made him feel “quite dizzy.”

“I told the Lord with deep conviction, ‘Don’t do this to me. You have younger and better [candidates] who could take up this great task with a totally different energy and with different strength,’” he told a group of German pilgrims soon after his inauguration as leader of the world’s 1.2 billion Catholics.

“Evidently, this time he didn’t listen to me,” Benedict added with a touch of the humor he displayed in private but seldom in public.

He had just turned 78 when his fellow cardinals picked him on April 19, 2005, a choice that pleased traditionalists but dismayed liberals who had hoped for a new direction on such issues as women’s role in the church, divorce and homosexuality. As he himself half-predicted, age began to catch up with him; the nonstop stress of visits to foreign lands, audiences with dignitaries, management problems in the Vatican and authoritative papal writings wearied him.

By the time he announced his intention to resign, Benedict was 85, frail and careworn, and had cut down on his public appearances. One visitor said later that the already-diminutive pope seemed thin and “halved in size,” and the Vatican revealed that Benedict had fallen and bloodied his head during a 2012 trip to Mexico.

“After having repeatedly examined my conscience before God, I have come to the certainty that my strengths, due to an advanced age, are no longer suited to an adequate exercise of the Petrine ministry,” the pope told a group of listeners Feb. 11, 2013, stunning those who understood the import of his remarks, which were delivered in Latin.

Some months later, Benedict revealed that he had decided to resign because “God told me to” during a months-long mystical experience, which had deepened his desire for a closer relationship with the divine. Seeing the galvanizing effect of his successor, Francis, on the church only strengthened his conviction that he had done the right thing, Benedict said.

In many ways, his short papacy was a coda to that of John Paul, whom he had faithfully served. Benedict kept the church on the same conservative path and eased restrictions on elements such as the Latin Mass. He appointed many of his and John Paul’s protégés to the College of Cardinals, ensuring that the upper ranks of the church were filled with men from the same theological mold.

But he took a different evangelistic tack from his globe-trotting, glad-handing predecessor, who had happily played up the church’s international profile and reached out to other religions. Benedict focused on trying to shore up Christianity in his native Europe, which he saw perilously adrift on a sea of godlessness, libertinism and moral indifference.

“We are moving toward a dictatorship of relativism, which does not recognize anything as certain and which has as its highest goal one’s own ego and one’s own desire,” he told cardinals at a Mass in St. Peter’s Basilica shortly before his election as pope.

He warned against following “the waves of today’s fashions” and exhorted devotees to embrace “an adult and mature faith” that enabled them “to judge true from false.”

God’s blessing and the church’s revival could be achieved by calling the faithful back to basics and promoting theological purity, Benedict believed.

Yet his attempt to rejuvenate the Roman Catholic Church in its own backyard failed by most measures, even as the church grew in faraway places such as Africa and Asia. Europe was the only region of the world where the number of Catholics declined between 1990 and 2010. The pews continued to empty; in France, fewer than 1 in 10 people reported attending Mass.

For many, disenchantment was fueled by what they considered the Vatican’s belated and inadequate response to the avalanche of allegations of priestly sexual misconduct dating back years, sometimes decades. Although Benedict met privately with victims and pledged greater cooperation with civilian authorities, his hesitation in disciplining bishops who covered up incidents of abuse angered those who saw the church as more concerned about its image than those hurt by its representatives.

In addition, the Vatican’s conservative teachings on sex, gender and family life struck many Europeans as increasingly retrograde. Despite Benedict’s vocal opposition, country after country moved to legalize same-sex marriage during his brief tenure as pope, including Spain, France, Portugal and Britain.

His emphasis on fundamental Christian values and the primacy of the Catholic Church also led to friction with Muslims and the first major crisis of his papacy.

In a 2006 speech at a German university where he once taught, Benedict cited a disparaging medieval quotation on Islam to illustrate the incompatibility of religion and violence. But his failure to mention Christianity’s own bloodstained past and the description of Muhammad’s teachings as “evil and inhuman” ignited a storm of criticism and protest in the Muslim world, including the killing of an Italian nun in Somalia.

He eventually apologized twice for his injudicious remarks but never retreated from his wider point, an example of what one person described as the “timid but stubborn” side to his personality.

Although he visited the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Blue Mosque in Istanbul, the pope criticized the way that he believed extremists had perverted Islam and argued for “reciprocity,” saying that if Muslims expected to worship freely in Christian lands, the reverse should also be true.

Benedict’s passionate faith was formed during his youth in southern Germany under the lengthening and darkening shadow of Nazism.

He was born Joseph Aloysius Ratzinger on April 16, 1927, in the Bavarian village of Marktl am Inn, the third child of a police officer and a cook who had met through a want ad in the local newspaper.

After the family moved to the nearby town of Traunstein, Joseph and his older brother, Georg, enrolled in a nearby seminary. But Catholicism was soon under threat from the Nazis, who held rallies in the local square. Crucifixes were removed from classrooms; Catholic youth groups met in secret. Fascist-leaning teachers began showing up in the seminary.

The Ratzingers despised the Nazis, biographers say.

“The family moved a lot because the father was not a sympathizer of the National Socialist Party and could not get ahead in the job, so they were always poor,” the auxiliary archbishop of Munich, Engelberst Siebler, told reporters in 2006.

But fearing retribution, Joseph joined the Hitler Youth, as did many other teenagers, and was assigned to an antiaircraft brigade. (Jewish groups later forgave him his membership, saying he had signed up out of fear, not conviction.) At 18, he was drafted into the army to dig trenches, but he deserted in 1945, just before Germany’s defeat, and was briefly held as a prisoner of war by U.S. forces.

The war helped instill in him the notion of the Catholic Church as a bulwark against evil that would prevail with God’s help.

“No one doubted that the church was the locus of all our hopes,” Ratzinger wrote in a memoir before he became pope. “Despite many human failings, the church was the alternative to the destructive ideology of the [Nazi] rulers; in the inferno that had swallowed up the powerful, she had stood firm with a force coming to her from eternity.”

He was ordained a priest in 1951, earned a doctorate from the University of Munich two years later and gained a reputation for deep erudition. In 1966, Ratzinger took up a teaching post at Tuebingen University, where he witnessed what he believed was another assault on Christian values, this time from Marxism and growing social liberalism.

Marxist student agitators would burst into his classroom, heckling and whistling. Ratzinger saw their disrespect and unruliness as part and parcel of a general societal descent into moral decay, materialism and atheism.

He was well on the path to theological conservatism when a fellow European, Pope John Paul II of Poland, noticed his talents and summoned him to join the Curia, the Vatican administration, in 1981. By then, Ratzinger had risen to become archbishop of Munich and a cardinal, one of the red-hatted “princes” of the church.

John Paul named him as head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the Vatican department responsible for enforcing Catholic orthodoxy.

It was an appointment rich in irony. The congregation was reorganized in the 1960s by Pope Paul VI to replace the church’s former anti-heresy office, in response to a report that Ratzinger had helped to write, a scathing critique of the office as a throwback to the Inquisition. Yet under John Paul and Ratzinger, the congregation was almost as harsh as it had been under their predecessors in its crackdown on any deviation from church dogma, branding dissent and liberal innovations as erroneous and corrupt.

Priests and nuns who questioned the official line on remarriage for divorced Catholics, celibacy for clerics or the prohibition on women as priests were silenced or reprimanded.

Most famously, Ratzinger helped censure his friend Hans Kung, a Swiss theologian skeptical of the concept of papal infallibility. He also clamped down on the Marxist-tinged liberation theology movement sweeping through Latin America and defined homosexuality as a “tendency ordered toward an intrinsic moral evil,” a position he bolstered as pope by frowning on gay men as candidates for the priesthood.

In some ways, as chief enforcer, Ratzinger served as bad cop to the good cop played by John Paul, who charmed the world with his humor and warmth.

“Ratzinger’s job is a thankless one,” a high-ranking Vatican official told The Times in 1986. “It’s inevitable that he would be seen as the fall guy. General civility within the church would avoid an overly blunt, personal attack on the pope.”

When John Paul died in April 2005 after 26 years at the helm of the church, few Vatican experts put odds on Ratzinger to succeed him, in part because of the white-haired cardinal’s age, in part because of his reputation, deserved or no, as God’s Rottweiler. His brother, Georg, who died in July 2020, worried his sibling’s health would suffer if he were elected pope and fretted that they’d no longer spend as much time together.

Yet in retrospect, Ratzinger was the obvious choice, the front-runner from the start. Traumatized by the beloved John Paul’s death, many of the cardinals sought continuity and comfort; Ratzinger offered that, having already taken charge of much of the Vatican during the pope’s long decline and delivering a moving eulogy at his funeral.

Inside Michelangelo’s magnificent Sistine Chapel, the cardinals elected Ratzinger in near-record time on the second day of their conclave. At 78, he was the oldest man to be made pope in 300 years.

Thousands of pilgrims in St. Peter’s Square cheered at his unveiling as Benedict XVI, a name chosen in honor of the pope who sought peace during World War I and of one of Europe’s patron saints, who pioneered Western monasticism and was “a powerful reminder of the indispensable Christian roots” of Europe, the new pontiff explained later.

That signaled the emphasis he would place on trying to revive Roman Catholicism on its home turf. He also brought back some of the trappings of his office, including the famous papal red shoes symbolizing martyrdom.

But just as Benedict the man could sometimes surprise people in private with his gentle humor, his fondness for Mozart and cats, Benedict the pope also sometimes surprised the flock. Belying his stern image, his first encyclical, the most authoritative form of papal writing, centered on love, one of three treatises he planned to write on the cardinal virtues of love, hope and faith. (The last one turned out to be a joint production with Francis.)

“In a world where the name of God is sometimes associated with vengeance or even a duty of hatred and violence, this message is both timely and significant,” Benedict wrote in the 71-page document, titled “Deus Caritas Est,” or “God Is Love.” “For this reason, I wish in my first encyclical to speak of the love which God lavishes upon us, and which we in turn must share with others.”

Benedict made two dozen official trips as pope, from the Americas to Australia, but the pace tired him.

So did the turmoil inside headquarters, where factionalism was rife, culminating in one of the biggest security breaches in Vatican history. The pope’s personal butler, Paolo Gabriele, was convicted in October 2012 of stealing thousands of internal documents that he then passed on to a journalist, whose account of infighting and allegations of corruption deeply embarrassed the Vatican.

Just four months later, Benedict announced his intention to resign, a decision he had managed to keep remarkably secret. While some Catholics protested that only God can remove a pope, others saw it as an act of grace that helped avoid a repeat of the increasing incapacitation suffered by John Paul II and that paved the way for future pontiffs to step down at the right time.

On Feb. 28, 2013, in a well-choreographed departure, Benedict left the Vatican and was flown by helicopter to the papal summer retreat of Castel Gandolfo outside Rome, a journey televised live around the world. At 8 p.m., his papacy officially ended, and he assumed the novel title of “pope emeritus.”

He pledged “unconditional reverence and obedience” to his successor, an effort to ease concerns over two competing pontiffs. Francis heartily welcomed Benedict back to the Vatican, where the former pope moved into his newly renovated quarters on the Vatican grounds to take up a life of contemplation, seclusion and writing, adding to his impressive output of more than 50 books.

“I’m fine. I pray and read. I live like a monk,” Benedict told a visitor. It was the ending he wanted.

Times staff writer Tracy Wilkinson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.