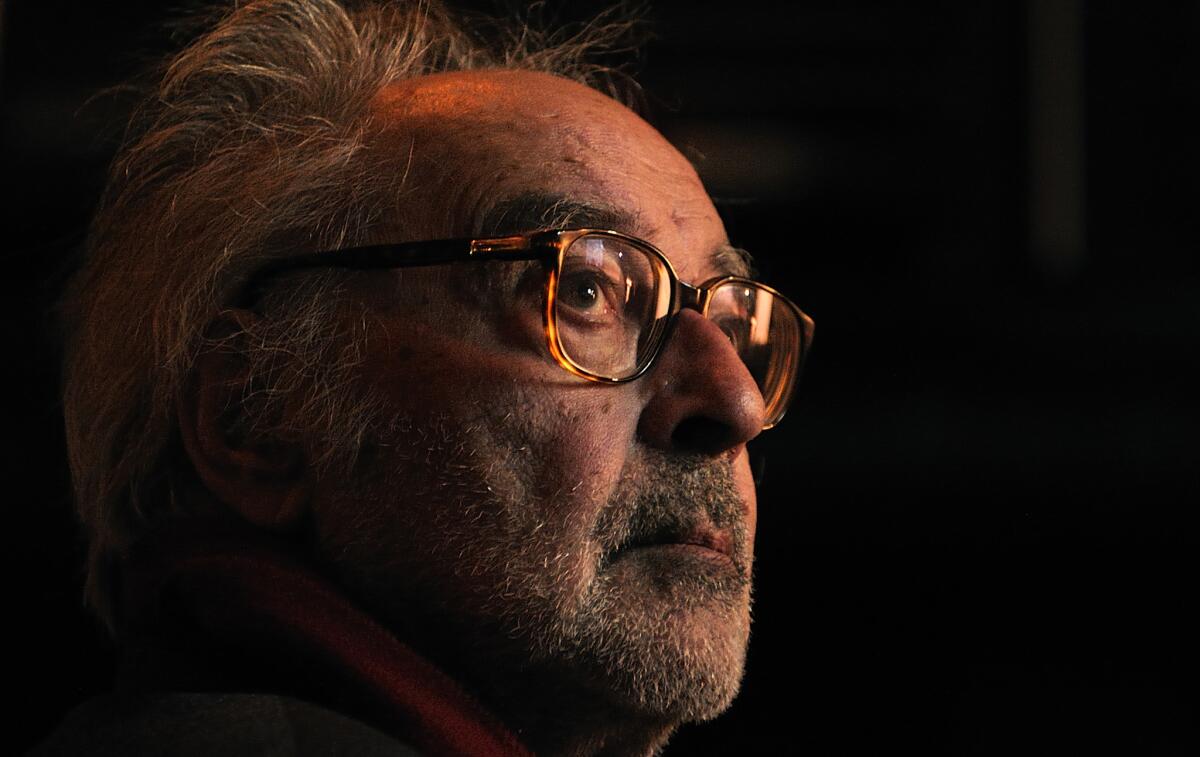

Jean-Luc Godard, deeply influential French New Wave filmmaker, dies at 91

Jean-Luc Godard, the influential French New Wave writer-director who broke new ground in cinematic expression in the 1960s with films such as “Breathless,” “Contempt” and “Weekend” and became a guiding light to fellow filmmakers throughout his more than six-decade career, has died. He was 91.

Godard died Tuesday morning at his home in Rolle, Switzerland, surrounded by his close relatives, his longtime legal advisor Patrick Jeanneret said.

“As he was affected by multiple medical conditions making his life difficult, he requested the suicide assistance which is allowed under Swiss law,” Jeanneret said in a statement to The Times. “He died in total dignity as he wished. There will be no official ceremony.”

The French news outlet Libération quoted an unnamed family member as saying Godard “was not sick ... he was simply exhausted.”

French President Emmanuel Macron hailed Godard as a “national treasure” who “invented a resolutely modern, intensely free art” with his pioneering works.

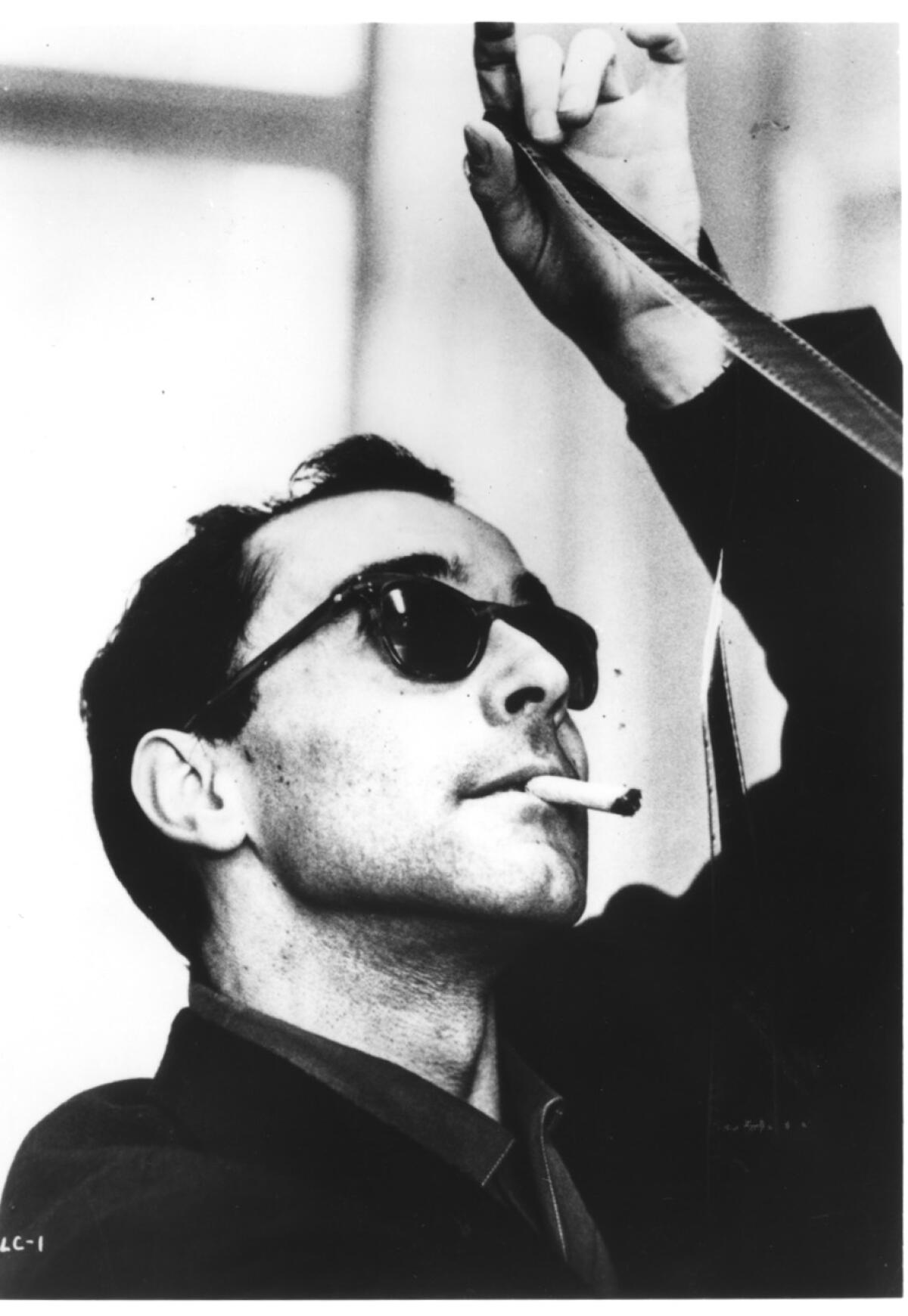

Forever content to forgo commercial success in exchange for artistic freedom, Godard was the most inventive and radical of the directors of the French New Wave, which upended European cinema in the 1950s and ’60s by reflecting their personal visions and challenging traditional filmmaking conventions.

Like fellow New Wave directors François Truffaut, Éric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette and Claude Chabrol, the movie-obsessed Godard came to filmmaking after being a critic. He was among the earliest contributors to the influential French film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma, the birthplace of the auteur theory, which asserts that the director can be the “author” of a film, in the same way a writer is the author of a novel.

“Godard was one of the inventors of the auteur theory and perhaps the most rigorous of the New Wave filmmakers in putting that idea into practice,” film critic David Sterritt told The Times in 2006.

“Every one of his films and videos is intensely personal to him and represents his own utterly unique views of the world and the people in it,” Sterritt said.

Jean-Luc Godard is nowhere to be found at the Swiss apartment building where he lives and works.

Godard had already directed several short films when, at 29, he captured international attention in 1960 with his first feature film, “Breathless,” a boldly innovative homage to American gangster B-movies.

Shot on location in Paris, the low-budget romantic crime-drama starred Jean-Paul Belmondo as an amoral young thug with a Humphrey Bogart fixation who is on the run after stealing a car and killing a cop. His love interest is an American girl, played by Jean Seberg, who winds up betraying him.

“Breathless” became famous for its rule-breaking use of hand-held cameras that circled the action, natural lighting, direct sound recording, jump-cut editing and sense of spontaneity — as well as for its unabashed references to Hollywood films.

“Modern movies begin here,” the late Chicago Sun-Times movie critic Roger Ebert wrote of “Breathless” in 2003. “No debut film since ‘Citizen Kane’ in 1942 has been as influential.”

Michel Hazanavicius can imagine what people think. I mean, he’s heard what people think.

During the 1960s alone, Godard directed nearly 30 shorts and features, including “Le Petit Soldat,” “A Woman Is a Woman,” “My Life to Live,” “Les Carabiniers,” “Band of Outsiders,” “A Married Woman,” “Alphaville,” “Masculin Féminin,” “Pierrot le Fou,” “2 or 3 Things I Know About Her” and “Weekend,” which famously features a tragicomic seven-minute tracking shot of a traffic jam created by a horrific crash.

By the late ’60s, Godard had embarked on what Sterritt called his “ultra-radical political phase” as a filmmaker.

As Julia Lesage wrote in her 1979 bibliography, “Jean-Luc Godard: A Guide to References and Resources”: “Godard seemed to be searching both for the best way to make a political film and the best way to integrate his métier, filmmaking, with militant Marxist-Leninist political activity.”

By the late 1970s, Sterritt said, Godard had returned to filmmaking geared slightly more to a theatrical audience, although the films remained artistically radical.

Anna Karina, who died Saturday in Paris at age 79, danced her way through a few of the seven films she made with Jean-Luc Godard.

“The important thing about Godard is he broke all the rules, and he showed that everything could be cinematic if your conceptualization — your ideas — were bold enough,” Marsha Kinder, a professor of critical studies at the USC School of Cinematic Arts, told The Times in 2006.

“No matter how apocalyptic or bleak his vision might be, his films made me feel hopeful because his brilliance and inventiveness were so dazzling,” Kinder said. “He just redefined what kind of pleasures cinema could give you.”

But for audiences, Kinder acknowledged, the rule-breaking Godard “could also be very exasperating.”

Indeed, Godard was well known for challenging his audiences.

“I don’t really like telling a story,” he once said. “I prefer to use a kind of tapestry, a background on which I can embroider my own ideas.”

And beginning with ideas, Godard said in a 1995 interview with The Times, “doesn’t help with the audience. But I still prefer a good audience. I’d rather feed 100% of 10 people. Hollywood would rather feed 1% of 1 million people. Commercially speaking, my way is not better.”

Godard’s films influenced countless filmmakers, including Martin Scorsese. While watching Godard’s movies as a film student in the ’60s, Scorsese said he was taken with the “sense of freedom, of being able to do anything — there was a kind of joy that burst into me when I saw the movies.”

This article was originally on a blog post platform and may be missing photos, graphics or links.

Another well-known fan, director Quentin Tarantino, named his production company A Band Apart after the French title (“Bande à Part”) for Godard’s 1964 film “Band of Outsiders” and heeded one of Godard’s maxims when he filmed “Pulp Fiction”: “A movie should have a beginning, a middle and an end, though not necessarily in that order.”

The late director Bernardo Bertolucci put it simply: “We all wanted to be Jean-Luc Godard.”

“There is no one like him in the whole history of cinema,” said Kinder. “He took his vengeance against Hollywood. He never stopped really attacking the dominance of Hollywood cinema, and he never stopped expanding the language and subversive possibilities of cinema.

“This makes him, I think, one of the greatest filmmakers in the history of world cinema. He made everything possible.”

One of four children, Godard was born in Paris on Dec. 3, 1930. His mother was the daughter of a wealthy Parisian banker, and his father was a Swiss physician who divided his work between Paris and Switzerland.

In 1933, Godard’s family moved permanently to Switzerland after his father landed a position at a clinic near the village of Gland. Five years later, they moved to Nyon, Switzerland, where they lived during World War II.

After the war, the 15-year-old Godard moved to Paris to study at the prestigious Lycée Buffon, a school that focused on the physical and biological sciences. He returned to Switzerland to attend a college in Lausanne in 1948, but a year later he was back in Paris, where he registered at the Sorbonne for a certificate in anthropology.

By then, however, Godard was so taken with cinema that he paid scant attention to his studies.

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

He said he had been a casual filmgoer until he began attending a Left Bank film club run by critic André Bazin, where he met future New Wave directors Truffaut, Rohmer and Rivette. He and his friends also regularly frequented Cinémathèque Française.

“We systematically saw everything there was to see,” he told Jean Collet, author of the 1970 book “Jean-Luc Godard.”

In 1950, Godard, Rohmer and Rivette co-founded the short-lived La Gazette du Cinéma, which published their film criticism; it lasted only five issues. After Bazin co-founded Cahiers du Cinéma in 1951, Godard started publishing essays there. He also began to learn filmmaking by acting in his friends’ short films.

For several years, Godard was also a petty thief, who stole repeatedly to support himself and was frequently caught, according to Colin MacCabe’s 2003 book, “Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at Seventy.”

Godard, MacCabe wrote, claimed to have financed Rivette’s first short film by stealing from an uncle. And in the early ’50s, after working for a company constructing dams in the Swiss Alps, Godard spent three days in jail after stealing from the Swiss television service he was then working for in Zurich.

After Godard was released from jail, his father convinced him to go to a Swiss mental clinic that specialized in psychotherapy.

After several months in the clinic, Godard returned to the construction company in the Alps, where he shot his first film, a 20-minute documentary on the construction of the dam, “Opération Béton.” He then directed a 10-minute comedy short in Geneva before moving back to Paris.

In 1961, Godard married Anna Karina, who starred in “A Woman Is a Woman,” “My Life to Live,” “Band of Outsiders” and other Godard films during the ’60s. His marriage to Karina ended in divorce — as did his marriage to Anne Wiazemsky, who starred in several of his films, including 1967’s “La Chinoise.” Godard later began a longtime relationship with his collaborator, Anne-Marie Miéville. The two moved to Switzerland in the ’70s.

Even setting aside her acclaimed work in the 1960s with the filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard, actress Anna Karina has a formidable career that includes working with directors Luchino Visconti, George Cukor, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Jacques Rivette, Tony Richardson and Jonathan Demme.

In recent decades, Godard worked in both film and video. And, Sterritt said, “what some consider his magnum opus, the crowning achievement of his career,” is Godard’s “Histoire(s) du Cinéma,” a multisegment video work launched in 1989. His later films included “Goodbye to Language,” a fragmented film in 3D about a young couple who communicate through their pet dog. His final feature, the 85-minute nonfiction “The Image Book,” premiered at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, where Godard was awarded the fest’s first Special Palme d’Or. In his review of the film, Times critic Justin Chang called it “a swirling, dazzling, maddening frenzy of disconnected sights and sounds.”

Late in life, Godard seemed pleased but baffled that critics were still examining his work. He conceded, however, that the audience for his films had grown small.

“I never understand why I’m remembered,” he once told The Times. “I always wonder why I’m still known because nobody sees my movies now. Well, almost nobody.”

McLellan is a former Times staff writer. Staff writers Christi Carras and Jen Yamato contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.