Adrianus Kalmijn, biophysicist who discovered sharks have a ‘sixth sense,’ dies

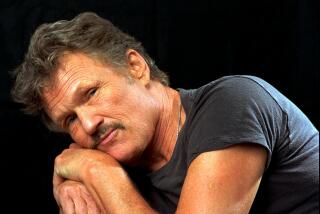

SAN DIEGO — Adrianus J. Kalmijn, the UC San Diego biophysicist who discovered that sharks can detect the weak electric field produced by other fish — giving them a “sixth sense” and a tremendous advantage in hunting prey — has died at 88.

Kalmijn died Dec. 7 in La Jolla from complications of acute myeloid leukemia, according to his son Jelger Kalmijn, a UC San Francisco researcher who often worked on his father’s projects.

The defining discovery of the elder Kalmijn’s professional life came in 1971, when he was a young scientist at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

It was widely known that sharks had an abundance of ways of sensing what was around them, especially through their sense of smell. Even a tiny droplet of blood could be picked up by sharks far, far away.

But Kalmijn and his collaborators took things further, showing experimentally that the tiny pores in the snout of sharks and skates served as receptors that picked up the electric signals of other fish, even if the fish were hidden beneath the sand or in close relation to food, such as chum.

This dazzled scientists, who said Kalmijn had essentially discovered that sharks have a “sixth sense,” one that also helps them in navigation. The finding added to the somewhat mystical reputation of sharks.

“His contribution to shark sensory biology is not just significant, it is monumental,” Kyle Newton, a Washington University of St. Louis researcher, said in a statement.

Kalmijn was born Nov. 7, 1933, in the Netherlands. His father, Joseph, was a high school math teacher. His mother, Johanna Kalmijn-Spierenburg, wrote children’s books.

After attending high school, Adrianus Kalmijn served in the military for about three years, where he learned about radar and signals. That experience helped him take a practical, applied approach to his work when he studied at Utrecht University in the Netherlands.

He later served on the university’s faculty and did extensive shark research at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, before he settled in for the long term at Scripps in the early 1980s.

With support from the Navy and the Keck Foundation, he built a major electromagnetic research facility that was in use for decades. Kalmijn’s findings greatly expanded science’s understanding of how sharks hear, as well as how their other senses work.

“My father felt a deep humility toward animals,” Jelger Kalmijn said. “He felt that they had so much to teach us about the world.”

He is survived by his wife Vera, children Jelger, Thera and Sander, and six grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.