Ed Asner, actor who played Lou Grant on ‘Mary Tyler Moore Show,’ dies at 91

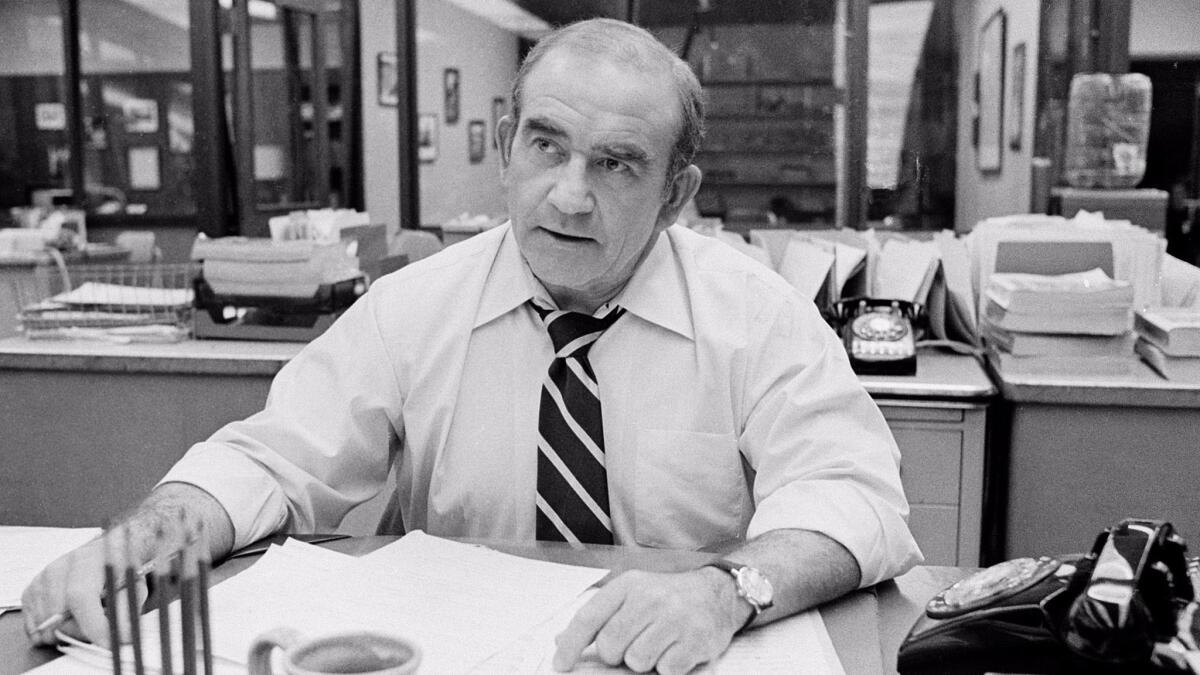

Ed Asner, whose Emmy Award-winning supporting role as the gruff but lovable Lou Grant on the 1970s situation comedy “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” led to his own Emmy Award-winning starring role in the spinoff dramatic series “Lou Grant,” has died. He was 91.

Asner, an outspoken liberal activist who served two controversial terms as president of the Screen Actors Guild in the 1980s, died Sunday in Los Angeles. Asner’s representative confirmed the actor’s death in an email to the Associated Press.

Asner’s official Twitter account included a note from his children: “We are sorry to say that our beloved patriarch passed away this morning peacefully. Words cannot express the sadness we feel. With a kiss on your head- Goodnight dad. We love you.”

Though his career was long and varied, Asner forever called Lou Grant “the greatest character I ever came across.”

In a memorable, character-defining scene in the first episode during which the middle-aged Grant interviews Moore’s perky Mary Richards for a job at WJM-TV in Minneapolis, he says with an admiring twinkle in his eyes: “You know what? You’ve got spunk. I hate spunk!”

Asner described the rumpled Grant, with his rolled-up shirt-sleeves and perpetually loosened tie, as an “everyman.”

“He radiates warmth, generosity and caring, someone who reflects a toughness over a mound of Jell-O, a nice degree of intelligence but a working intelligence as opposed to an arrogant one,” he told The Times in 1977.

Asner’s portrayal of the hard-nosed newsman with the soft center struck a chord with viewers, particularly journalists.

“I guess I was able to achieve that newsroom boss-man image. All the letters say, ‘I once had an editor just like you,’” Asner said in the 1977 interview.

For his work on “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” Asner won three Emmys — two for actor in a supporting role in comedy and one for continuing performance by a supporting actor in a comedy series.

After “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” ended, Asner’s character resurfaced as the hard-hitting city editor of the Los Angeles Tribune on “Lou Grant.”

The hourlong dramatic series, which ran on CBS from 1977 to 1982, won two Emmys and a Peabody Award for its “entertaining yet realistic look at the problems and issues which face those involved in the Fourth Estate.”

The series also garnered Asner two Emmys for lead actor in a drama series, making him the only actor to win Emmys for playing the same character in both a comedy and a drama.

Asner also won two other Emmys — for his roles as the patriarch in the 1976 miniseries “Rich Man, Poor Man” and as a slave-ship captain in the landmark 1977 miniseries “Roots.”

In 1980, while starring in “Lou Grant,” Asner was an outspoken and highly visible Screen Actors Guild member on the picket line during a three-month actors strike. The self-described “union loyalist” was elected SAG president the following year.

Throughout his time as president — he was reelected in 1983 — Asner engaged in a bitter battle with the union’s conservative wing spearheaded by Charlton Heston, a former SAG president. They fought over Asner-supported issues such as merging SAG with the Screen Extras Guild, which was defeated; and Asner’s attempts to involve the guild more in the political arena.

At the time, Asner said that the conservative attack on him began early in his presidency when he and other guild leaders rejected President Reagan, himself a past SAG president, as the recipient of the guild’s highest honor, the Screen Actors Guild Award.

Heston called the rejection of Reagan a “gross blunder, and another example of the radicalization of the guild.”

In February 1982 — four months after his first election — Asner, a founding member of Medical Aid for El Salvador, faced a barrage of criticism after he and a couple of other prominent actors traveled to Washington and presented a fundraising check for $25,000 to be used for medical aid to leftist rebels in El Salvador, who were fighting the U.S.-backed military dictatorship.

“Mr. President, your enemies are not our enemies,” Asner reportedly said on the steps of the State Department.

Although his guild critics said they did not object to Asner’s support of any cause as a private citizen, The Times reported, they strongly objected to his remarks on El Salvador because he did not make it clear that he was not speaking as president of the guild.

In heading off a recall drive over the incident, Asner called a news conference in Hollywood to announce the near-unanimous vote of the union’s board of directors in support of his right to speak out on political matters as a private citizen.

Admitting that he had made “a slight goof, an honest mistake” for not making it clearer that he was not speaking on behalf of the guild during his Washington appearance, Asner said that in the future he would make certain that it was understood whether he was speaking publicly as the guild’s president or as a private citizen voicing his personal views.

“I have an obligation to speak out for the cause of justice and to protest human misery and will continue to do so,” he said at the news conference, adding that neither his sponsors nor CBS had asked him to tone down his views as a private citizen.

In the wake of widespread criticism for his fundraising drive for medical aid to El Salvador, which Asner viewed as “strictly a humanitarian activity,” a campaign urging a boycott of “Lou Grant” sponsors was launched and a few sponsors reportedly pulled their commercials from the show.

In May 1982, three months after Asner’s appearance in Washington, CBS canceled “Lou Grant.”

The network attributed the cancellation solely to the show’s drop in ratings. But Asner saw it differently, saying CBS’ decision to cancel the series at a time when he was under political attack “showed cowardice.”

Although Asner later said, “the price you pay for activism in this town is a big one,” he continued to speak out.

Over the years, he supported a number of political and charitable causes, including Amnesty International, the American Civil Liberties Union, Death Penalty Focus, Defenders of Wildlife and Peace Now.

He also continued to speak out on union issues, including joining other entertainment-industry figures to form a group to lobby producers and networks for more roles for older actors.

“I’m always thought of in Hollywood and surrounding environs as the resident communist,” Asner told The Times in 2010.

Asner received the Screen Actors Guild’s Ralph Morgan Award for distinguished service to the Hollywood branch in 2000. And in 2002, he received the guild’s Life Achievement Award.

News of Asner’s death elicited an outpouring of emotion. “There have been few actors of Ed Asner’s prominence who risked their status to fight for social causes the way Ed did,” said current SAG-AFTRA President Gabrielle Carteris on the union’s website. “He fought passionately for his fellow actors, both before, during and after his SAG presidency. But his concern did not stop with performers. He fought for victims of poverty, violence, war, and legal and social injustice, both in the United States and around the globe.”

Pixar Animation Studios, for whom Asner starred in the Academy Award-winning 2009 film “Up,” posted on Twitter that “Ed was our real life Carl Fredricksen: a veneer of grouch over an incredibly loving and kind human being. Russell, Dug, and all of us at Pixar will miss him terribly.”

Filmmaker Michael Moore tweeted: “Making my 1st film, Roger & Me, I was broke so I wrote to some famous people to ask for help. Only one responded: Ed Asner. ‘I don’t know you, kid, but here’s 500 bucks’ said the note attached to the check. ‘Sounds like it’ll be a great film. I was an autoworker once.’ R.I.P. Ed.”

The son of a junk dealer and the youngest of five children, Asner was born Nov. 15, 1929, in Kansas City, Mo., and grew up in Kansas City, Kan.

In high school, he was an all-city tackle on the football team, worked on the school newspaper and had his first acting experience in a radio class that broadcast a weekly 15-minute program over a local station.

Asner made his stage debut at the University of Chicago as Thomas Becket in “Murder in the Cathedral,” but dropped out of college after two years. Returning home, he worked a series of jobs, including selling shoes and driving a cab. He later worked in a steel mill in Gary, Ind., and on an auto assembly line.

Drafted into the Army in 1951, Asner served in the Signal Corps in France. After his discharge in 1953, he joined the Playwright’s Theatre Club in Chicago, where he acted in 26 plays in two years.

In 1956, a year after moving to New York City, he joined the cast of the long-running Off-Broadway production of “The Threepenny Opera” and played Mr. Peachum for nearly three years. In 1960 he debuted on Broadway in a small part in the short-lived “Face of a Hero,” starring Jack Lemmon.

After moving to Los Angeles in 1961, Asner landed guest roles on TV series and played a supporting role as a veteran newspaper reporter covering the statehouse in the 1964-65 political drama “Slattery’s People,” starring Richard Crenna.

During the 1960s, Asner also appeared occasionally in films such as “The Slender Thread,” “Gunn,” “El Dorado” and “Change of Habit.” Later film credits included “Fort Apache, The Bronx,” “JFK” and “Elf.”

After “Lou Grant,” Asner starred in the 1985 sitcom “Off the Rack,” the 1987-88 dramatic series “The Bronx Zoo” and the 1994-95 sitcom “Thunder Alley.”

In 2009, he toured the country in the one-man show, “FDR.” He continued to make guest appearances on shows such as “The Good Wife” and “Modern Family.”

Fiery until the end, Asner unloaded on the far right in his late-in-life book “The Grouchy Historian: An Old-Time Lefty Defends Our Constitution Against Right-Wing Hypocrites and Nutjobs,” which was published in 2017. The following year, he and coauthor Ed Weinberger — an award-winning television writer — discussed the book at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books.

McLellan is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.