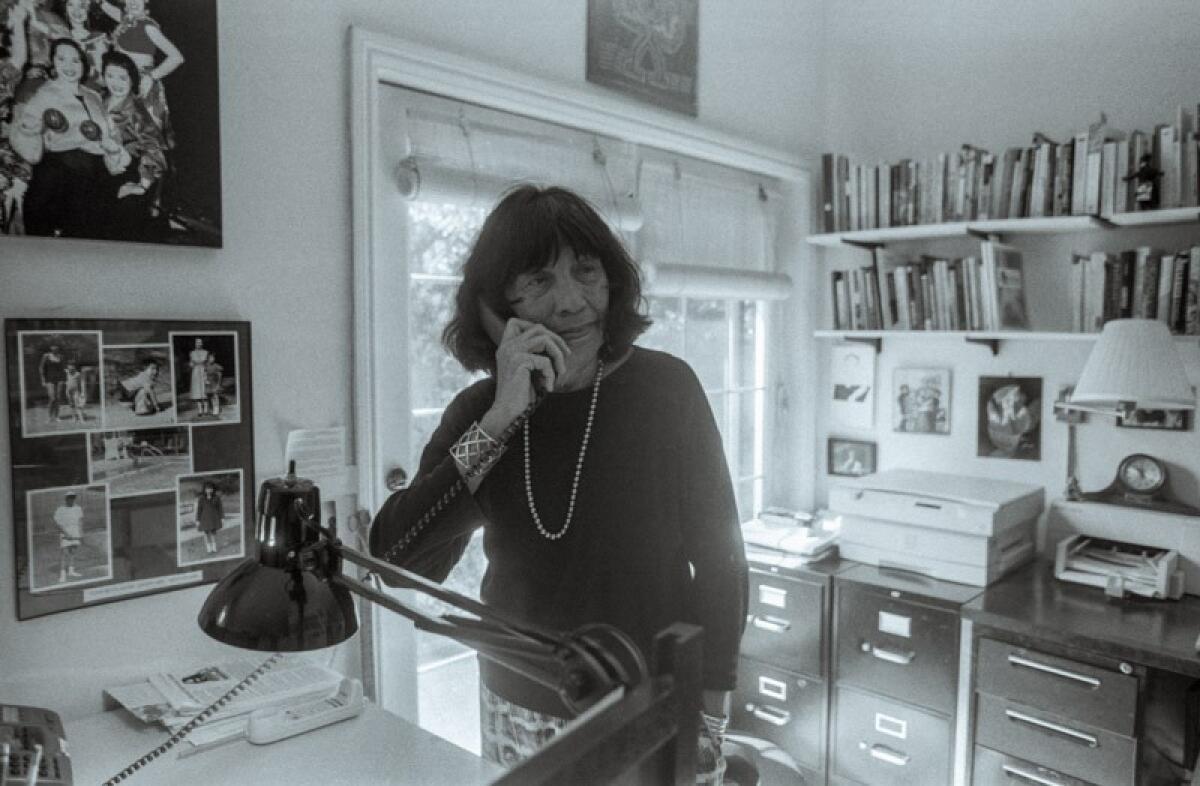

Elizabeth ‘Betita’ Martínez, prolific author and pioneering Chicana, dies

At 21, Elizabeth “Betita” Martínez worked as a clerk, translator and researcher for the newly formed United Nations. As part of her duties, the recent college graduate read reports published by colonial powers, describing how they controlled territories.

It didn’t take Martínez long to realize the link between colonialism and racism. The reports painted a grim reality of neglect and exploitation. In one instance, she learned Belgium provided one doctor for 100,000 people in the territory of Rwanda-Urundi.

Martínez and her boss couldn’t stand the injustice, so they leaked these documents to Third World delegates. Only then could they publicize and embarrass the colonial powers. The Philippines took the bait and announced the damning information during a Trusteeship Council meeting in Geneva.

The United States delegation heard about their scheme and reported her. Martínez’s Yugoslav boss fired her immediately but it was worth it. “That’s the most we could do from sitting inside the U.N., but that was a lot of fun,” Martínez said in 2006.

It was classic Martínez: perpetually overlooked and underestimated as a woman and Latina, but always getting the final word. Her boss rehired her the next day but the moment marked the beginning of a lifelong career in global activism. Weaving in and out of different social justice causes to elevate marginalized people, she focused on racial unity and intersectionality decades before it became essential to do so.

Active until the end, Martínez died early Tuesday at Laguna Honda Hospital in San Francisco, said Tony Platt, a close friend. She was 95.

“She was an example of what it means to not just speak your truth but to live your truth and to be prepared to commit your life to that truth,” said Elena Featherston, an educator and writer who worked alongside Martínez. “She’ll be remembered in a multitude of ways and it’ll be different for people.”

“She was an innovative type of organizer,” Chicana political activist Olga Talamante said. “In all projects, she had a posse of young people working with her. She loved being around young people and they loved being around her.”

Martínez grew up in a segregated suburb of Washington, D.C., the daughter of a Mexican father, a Spanish literature professor at Georgetown University, and American mother, an advanced Spanish high school teacher. She was neither Black or white, and yet she was scolded by her father when she tried to eat with a Black maid in her home. She didn’t know the word for it at the time, but she felt racism all around her.

After college, she strategically dropped her father’s last name for her mother’s middle name, “Sutherland,” to break into New York’s industry. She went on to work at reputable institutions such as Simon & Schuster and made a name for herself that could’ve guaranteed a modest life with a steady income for her and her daughter, Tessa Koning-Martínez.

Instead, Martínez traveled the globe in the name of social justice beginning in the 1960s. She went to Cuba, where she mingled with revolutionaries and was flagged by the FBI. In Mississippi, she used her publishing skills to promote the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the main student civil rights group in the U.S., at the time. And she joined the New York Radical Women, a predominantly white, middle class collective, and contributed to its feminist journal.

The work was taxing and it took a toll on her financial and mental health. The sexism and racism within so-called progressive groups repulsed her but she kept it to herself. Eventually, Martínez felt lonely. “It’s time for me to search for my identity,” she wrote to herself in a memo. “It’s time to go home to my Mexican-Americans.” So she left the East Coast and headed to New Mexico in 1968.

After years of identifying as “Sutherland,” she turned into Betita Martínez in the Land of Enchantment. “A voice inside of me said, ‘you can be Betita Martinez here,‘” she wrote.

She became the founding editor of El Grito del Norte, a pioneering community newspaper that documented the struggles of Hispanos and Mexicans reclaiming land grants from the U.S. government. She taught women how to write stories, encouraged travel to educational conferences and instilled unity among them. Their work gained national recognition from luminaries such as Talamante.

“It’s an incredible thing when you think about a 30-year-old woman really being able to organize teenagers and get them really radicalized and working with them to develop coalitions that produce ‘500 Years of Chicano History in Pictures’ and El Grito del Norte and comic books,” said Sofía Martínez, coordinator of Los Jardines Institute in Albuquerque.

“She had a lot of experience and history but she was always looking up to the next generation,” said Martínez’s daughter, Koning-Martínez. Her mother, she added, thrived on youths’ energy and insight.

It was in New Mexico where she wrote “500 Años del Pueblo Chicano/500 Years of Chicano History in Pictures,” a bilingual photo book with copious captions that illustrated the history of Chicanos in the Southwest. Published in 1976 by the Southwest Organization Project, it quickly became a staple of Chicano Studies classes but also was banned by Tucson Unified School District during Arizona’s war against ethnic studies. She followed that in 2007 with “500 Years of Chicana Women’s History/500 Años de la Mujer Chicana.”

By the final phase of her political life, she moved to the Mission District in San Francisco in 1974 and maintained her jampacked schedule of activities until she no longer could. She joined the women-led Democratic Workers Party, served as editor for the party’s newspaper and even ran for governor on the Peace and Freedom Party ticket in 1982. She fostered alliances among people of color by helping found the Institute for MultiRacial Justice. She also took time for self-reflection as a mother and on the movement, heeding caution on the dangers of hierarchical leadership.

“She was someone that could survive on less sleep than anyone I know. She didn’t make a lot of time for meals,” Platt said.

She also was notorious for calling friends near midnight on any given day. Despite being fluent in Spanish, English and French, oftentimes she required her colleague’s assurance that her Spanish-to-English translations captured the writer’s meaning. “It’s not like we’re working in a company and she’s the supervisor — it was more like, ‘This is Betita,’” Talamante said.

In 2000, the National Assn. for Chicana and Chicano Studies recognized her as scholar of the year. She also received an honorary doctorate from her alma mater, Swarthmore College.

Outside the political arena, she was always the life of the party. She loved her white go-go boots and rocked mini skirts even after her daughter abandoned that style. She enjoyed drinking gin martinis and wine with friends in her backyard, listening and singing to boleros and the Beatles and doting on her dogs.

Martínez is survived by her daughter.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.