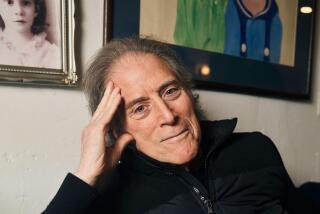

Norman Lloyd, a Hitchcock villain who later saved lives on ‘St. Elsewhere,’ dies at 106

Norman Lloyd, who memorably fell to his death from the Statue of Liberty as the villain in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Saboteur” in the 1940s but became best known four decades later as kindly Dr. Daniel Auschlander on TV’s “St. Elsewhere,” has died at his home in Brentwood.

Lloyd, who was also a director and producer, died Tuesday, said Dean Hargrove, a television producer and longtime friend. He was 106 and was generally considered to be the world’s oldest living film actor, working into his 90s.

On “St. Elsewhere,” the medical drama set in the seedy St. Eligius Hospital in Boston, Lloyd played Dr. Auschlander during the show’s six-season run, from 1982-88.

The hospital’s veteran physician was fighting a battle with liver cancer and was supposed to die in the show’s fourth episode.

“But somehow the character caught on,” Lloyd told the AP in 1985. “The joke around the show is that he’s got the longest remission in history.”

Lloyd said his character’s illness generated great public interest. “I get a lot of mail from people who have a terminal illness or whose relatives do,” he said. “It’s like they’re reaching out for an Auschlander.”

Lloyd later played Dr. Isaac Mentnor on the 1998-2001 science-fiction TV series “Seven Days.”

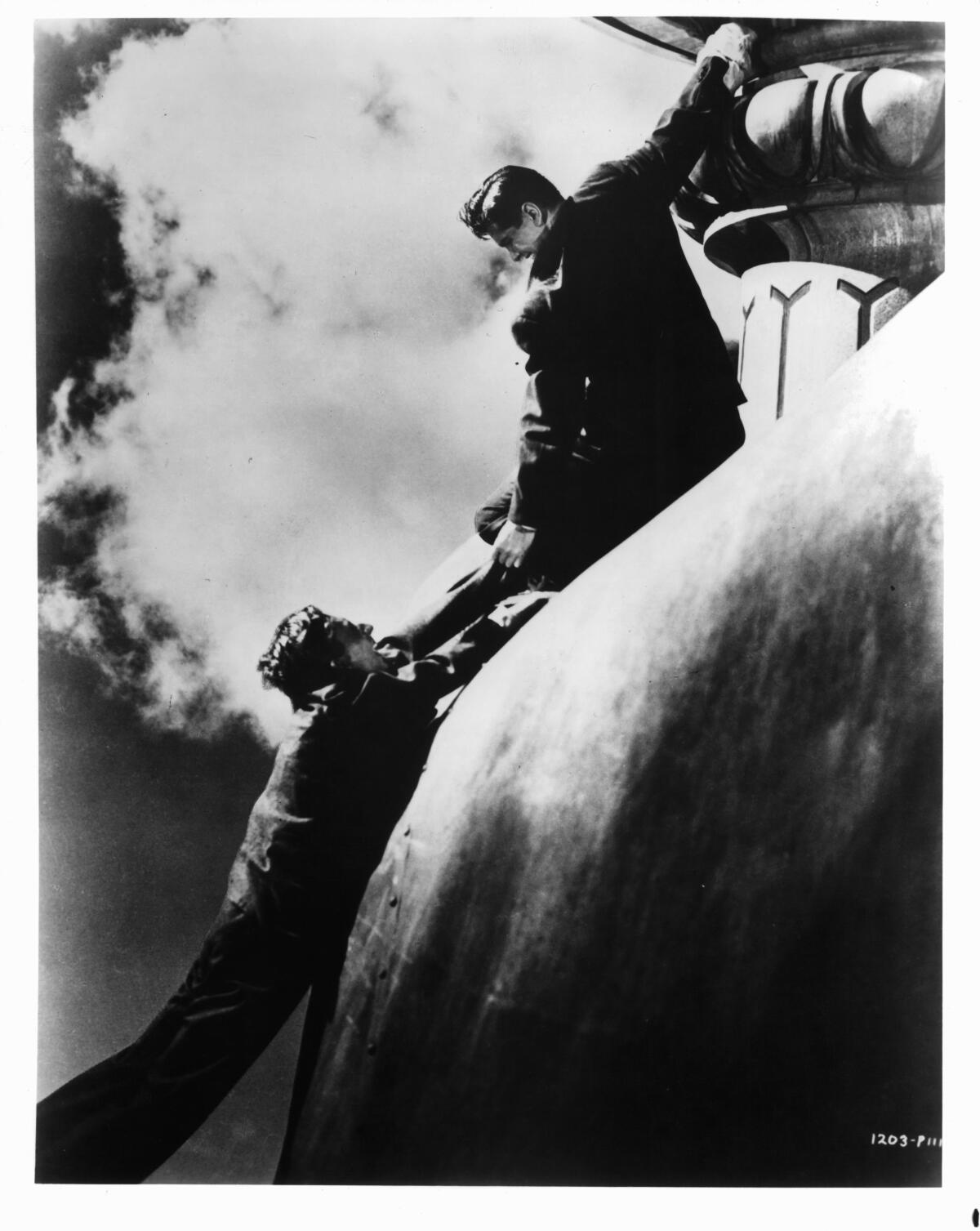

Film buffs, however, remember him as the furtive villain in Hitchcock’s “Saboteur,” the 1942 wartime thriller starring Robert Cummings as a Los Angeles aircraft worker who evades arrest after he is unjustly accused of sabotage.

Lloyd played Frank Fry, the real saboteur, whom Cummings’ character, Barry Kane, pursues across the country to clear his name. They wind up on the small balcony outside the crown of the Statue of Liberty for one of Hitchcock’s most stunning climaxes.

When Cummings’ Kane pulls a gun and gestures toward Lloyd’s Fry with it, Fry panics. He goes over the balcony railing but manages to hold onto the area between the statue’s thumb and forefinger with both hands. Because Fry must be taken alive to be persuaded to talk, Kane climbs down the forefinger to try to rescue him.

Kane then pulls on the dangling Fry’s coat sleeve to bring him closer. But the seam of the coat begins to rip, and when the sleeve parts from the coat, Fry falls to his death at the base of the statue.

Amazingly, the dramatic shot of the fall, which began with a close-up of Fry, was done without a cut.

In “Stages: Of Life in Theatre, Film and Television,” his 1990 book based on his oral history for the Directors Guild of America, Lloyd explained that the shot was done at Universal Studios with mock-ups of the statue’s thumb and forefinger attached to a platform. The platform, with a hole cut in it for the camera, was on counterweights and rigged to the top of the soundstage.

Beneath the platform was a saddle-like device on which Lloyd sat, on a pipe about 4½

feet high, based on a black cloth.

On cue, the camera started with a close-up of him, then went up in the air to the grid, “together with the set piece of the thumb and forefinger, leaving me behind; thus giving the effect of falling.

“This was shot at different speeds, while I did movements of falling rather slowly and balletically. By the time the camera got to the top of its move, it had gone from an extreme close-up to a very long shot of my apparently falling figure. The small saddle was not visible; the pipe and black cloth, which were seen, were later painted out in a traveling matte shot.”

Of Lloyd’s performance on the statue, Hitchcock once dryly commented, “No one could have dangled better than Norman.”

The mellifluous-voiced actor’s more than 70-year career spanned theater, film, radio and television.

As a young New York actor in the 1930s, he was a member of the Theatre of Action, the Federal Theatre, the Mercury Theatre and the Group Theatre — and worked with legendary directors Max Reinhardt, Joseph Losey, Elia Kazan and Orson Welles.

After making his film debut in “Saboteur” in 1942, Lloyd played character parts in 21 films over the next 10 years, including Hitchcock’s “Spellbound,” Jean Renoir’s “The Southerner,” Losey’s “M,” Charles Chaplin’s “Limelight” and Lewis Milestone’s “A Walk in the Sun.”

In the early 1950s, Lloyd frequently directed productions at the La Jolla Playhouse. He also turned his attention to directing for television. His credits included “Mr. Lincoln,” five half-hour films written by James Agee that aired on the acclaimed cultural series “Omnibus.”

But Lloyd discovered he was a victim of the Hollywood blacklist when producer John Houseman tried to cast him in the 1953 film “Julius Caesar.” He returned to the theater until Hitchcock wanted him for a job as associate producer of his TV series “Alfred Hitchcock Presents.”

“The network told Hitch, there’s a problem with Lloyd, and he simply said, ‘I want him.’ They all could have done that,” Lloyd told the New York Post in 2007, his voice rising in anger. “But they were cowards. It was Hitch who freed me.”

From 1957-62, Lloyd served as associate producer of “Alfred Hitchcock Presents,” for which he also directed 19 episodes. He went on to produce and then executive produce “The Alfred Hitchcock Hour” from 1962- 65.

“While Hitchcock oversaw production, Lloyd and fellow producer Joan Harrison were largely responsible for the creative quality of that show,” Mark Quigley, manager of research and study center for the UCLA Film and Television Archive, told The Times. “Lloyd’s artistic sensibilities are incredibly sophisticated for a network TV series.”

In the 1970s, Lloyd was executive producer — and served as a producer and a director — of PBS’ acclaimed dramatic anthology “Hollywood Television Theater.” He also produced and directed episodes of the 1979-88 TV series “Tales of the Unexpected.”

Returning to the big screen as an actor in 1977, Lloyd appeared in “Aubrey Rose” and “FM” a year later. He went on to play the stern headmaster in Peter Weir’s “Dead Poets Society” and the upper-class family lawyer in Martin Scorsese’s “The Age of Innocence.”

More recently, in his 90s, he played the blind retired literature professor who asks Cameron Diaz, as an assisted living center aide, to read to him in the 2005 comedy-drama “In Her Shoes.”

Born in Jersey City, N.J., on Nov. 8, 1914, and raised in Brooklyn, the red-haired Lloyd began taking elocution lessons by age 7. Those were followed by dancing and singing lessons, and for a time he occasionally did a song-and-dance act at benefits in theaters and at civic clubs.

After graduating from high school at 15, he entered New York University as a general arts major. He dropped out after his sophomore year in 1932 and auditioned for — and was accepted as one of 25 young men — an apprenticeship at Eva Le Gallienne’s Civic Repertory Theater in Manhattan, opening the doors to his future career.

A rabid baseball fan, Lloyd saw Babe Ruth play in the 1926 World Series, watching as the Sultan of Swat ripped the seat of his pants sliding into second base. Ninety-one years later, at age 102, he finally got to attend another Fall Classic, this time in Dodger Stadium, where he watched his beloved Dodgers take on — and lose to — the Houston Astros in 2017.

“It is wonderful to be at a World Series again,” Lloyd said as he settled into his left-field seat.

Lloyd’s wife of 75 years, actress Peggy Craven, died in 2011.

McLellan is a former Times staff writer. Staff writer Christie D’Zurilla contributed to this story.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.