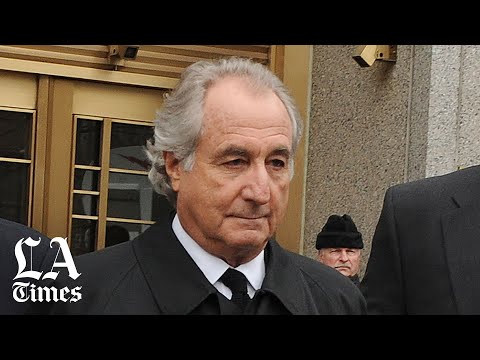

Bernie Madoff, notorious financier who pulled off history’s biggest swindle, dies at 82

Bernie Madoff, who came to epitomize Wall Street corruption with his epic $65-billion Ponzi scheme, has died in prison of natural causes at age 82.

It was one of history’s greatest swindles, a con so audacious and far-reaching that it came to epitomize Wall Street corruption, if not sheer greed itself.

A titan of the stock market once revered for what seemed to be his unfailing Midas touch, Bernie Madoff ran an epic $65-billion Ponzi scheme — unprecedented in size and global reach — that wrought devastation upon deep-pocketed institutions, scores of charities and thousands of investors around the world as the financial system convulsed in crisis in 2008.

In its wake, the nation’s economy plunged into the worst downturn since the Great Depression.

Twelve years into a 150-year prison sentence, the 82-year-old Madoff died early Wednesday of natural causes at the Federal Medical Center in Butner, N.C., according to the federal Bureau of Prisons. In poor health with kidney failure, hypertension and heart problems, Madoff asked last year to be released because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The request was denied.

Madoff’s long-running fraud easily dwarfed all previous scams, including that of Charles Ponzi himself a century ago. Its stunning revelation exposed deep flaws in the federal government’s ability to police Wall Street, deepening investor mistrust and prompting a major overhaul of the Securities and Exchange Commission.

“Not only was it the biggest of any of these schemes, but the amazing thing is that it went on for the better part of two decades,” said Richard Sylla, a financial historian and chairman of the Museum of American Finance.

Once regarded as an elder statesman of Wall Street, Madoff helped usher in an era of computer-driven trading as he took on the powerful New York Stock Exchange. He chaired the all-electronic Nasdaq stock market and even served on the board of the financial industry’s own regulator.

Such stature helped attract investments from politicians, corporate executives, Hollywood celebrities and executives, Florida country club members, nonprofits, pension funds and universities. For years, they all enjoyed double-digit returns that were consistently strong but not exorbitant enough to arouse widespread suspicions.

In truth, Madoff’s investors’ profits came not from trading in stocks or options but from new cash lured into a Ponzi scheme of massive proportions. Among those betrayed were some of the country’s biggest names: talk-show impresario Larry King, Nobel laureate and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel and then-New York Mets owner Fred Wilpon.

Jewish communities were particularly hard-hit. In Southern California, the Jewish Federation of Greater Los Angeles and the Jewish Community Foundation of Los Angeles suffered millions of dollars in losses, as did foundations bankrolled by movie director Steven Spielberg and Hollywood executive Jeffrey Katzenberg.

Many of Madoff’s individual victims suffered extreme personal hardship. Some had to sell their homes after what they thought were conservative investments evaporated; others found themselves forced into looking for work long after they had retired.

Deep depression was all too common, said Ron Stein, president of the Network for Investor Action and Protection, an advocacy group formed after Madoff’s scheme came to light. In one extreme case, a prominent French investor slashed his wrists, killing himself in his midtown Manhattan office.

“It’s terrible,” said Stein, whose wife’s family invested with Madoff. “The sense of frustration, the sense of betrayal, the sense of having given up — it’s mind-boggling.”

The cleanup of Madoff’s fraud added even more pain for many. Hapless investors faced years of grueling litigation by a court-appointed trustee who was tasked with “clawing back” what turned out to be fictitious profits they withdrew from their Madoff accounts.

In the end, Madoff robbed his investors of an estimated $20 billion in cash, excluding the phony paper profits that proved to be a mirage when he confessed to his two sons on the eve of his arrest by FBI agents on Dec. 11, 2008.

“I had been successful in a business, taking on the New York Stock Exchange — so, I figured, why can’t I manage money? Why can’t I do this too?” Madoff told journalist Diana Henriques, who chronicled Madoff’s fraud in her 2011 book, “The Wizard of Lies.” “I never believed that I was stealing. I thought I was taking a business risk, like I did all the time. I thought it was a temporary situation.”

The revelation of Madoff’s Ponzi scheme capped a decade that saw public confidence in corporate America severely shaken. First came the massive accounting frauds at Enron Corp. and WorldCom. Later, the demise of the storied investment bank Lehman Bros. in 2008 sent the stock market into a free fall, prompting the flood of withdrawals by Madoff’s skittish investors that eventually forced him to come clean.

When it came time for Madoff’s punishment, Denny Chin, then a federal district judge presiding over the case, seemed to channel the public’s growing outrage toward white-collar criminals. Chin imposed a symbolic sentence — the maximum — a century and a half behind bars.

“Here the message must be sent that Mr. Madoff’s crimes were extraordinarily evil, and that this kind of irresponsible manipulation of the system is not merely a bloodless financial crime that takes place just on paper but … one that takes a staggering human toll,” the judge said at Madoff’s 2009 sentencing in a packed, ornate, wood-paneled ceremonial courtroom in Manhattan.

But Madoff never explained himself to the satisfaction of government investigators, or attorneys and forensic accountants digging through the wreckage of his firm, Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities. He claimed his fraud started in the early 1990s, whereas the government claimed it stretched back more than four decades.

Madoff offered no justification for his crimes. At his sentencing, Madoff apologized to his victims and said he felt terrible for the harm he caused the financial industry and regulators who failed to catch him. He blamed his own hubris, which led him to dig himself deeper and deeper into a hole he said he could not escape.

“I made an error of judgment,” he said. “I refused to accept the fact that for once in my life I failed. I couldn’t admit that failure, and that was a tragic mistake.”

In subsequent prison interviews with journalists, Madoff said he apportioned some fault to individual investors who he suggested should have been less credulous. He claimed that major Wall Street banks and hedge funds surely must have known something was wrong but simply looked the other way.

JPMorgan Chase & Co., the nation’s largest bank, wound up paying $2.6 billion in penalties to federal prosecutors and regulators over its failures to heed red flags in its dealings with Madoff.

Ira Sorkin, a prominent New York criminal defense attorney who represented Madoff even though his father invested in his scheme, said his client never got enough credit for his remorse. Madoff bore the brunt of public disillusionment with Wall Street as the housing and stock markets plummeted in the throes of the Great Recession.

“He was the easy target. You couldn’t point a finger at Bear Stearns. You couldn’t point a finger at Lehman Bros.,” Sorkin said, referring to two investment banks that collapsed in 2008. “Madoff was easy, and because it was easy to understand, he was the target of the wrath of the press and the public.”

Aiding the fraud was a network of “feeder funds” and outside investment advisors that were a go-between for many investors and Madoff. Prominent among them was Stanley Chais, a Beverly Hills money manager whose clients lost hundreds of millions in Madoff’s fraud. Chais, who died in 2010, maintained he never knew of the scheme.

Madoff’s own relatives, many of whom also entrusted money to him, suffered for years under the glare of intense media and legal scrutiny.

His younger brother Peter, who was Madoff’s longtime chief compliance officer, was his only relative to face prosecution along with 13 other former employees. Peter Madoff spent nine years in prison for helping to conceal the fraud by misleading investors and regulators with phony records. He denied knowing of his brother’s fraud.

Bernard Madoff’s elder son, Mark, hanged himself with a dog leash in his Manhattan apartment in December 2010. His father didn’t attend the funeral.

His wife, Ruth, lost all the trappings of their once charmed life. She lost the couple’s penthouse on Manhattan’s ritzy Upper East Side neighborhood and moved to Florida, where she lived off $2.5 million she was able to keep in a settlement with the trustee overseeing the liquidation of Madoff’s assets.

“What he did to me, to my brother, and to my family is unforgivable,” Madoff’s younger son, Andrew, told “60 Minutes” in 2011. “What he did to thousands of other people, destroyed their lives — I’ll never understand it. And I’ll never forgive him for it. And I’ll never speak to him again.”

Andrew Madoff died of mantle cell lymphoma in 2014.

Bernard Lawrence Madoff was born April 29, 1938, and grew up in a middle-class section of the New York City borough of Queens. His mother worked a clerical job and his father at one point started his own sporting goods business and later started a stock brokerage, Henriques wrote.

Around the time he graduated from Hofstra University, on Long Island, in 1960, Madoff founded his stock-trading firm.

It was a tiny operation at first. He initially used a spare desk at his father-in-law’s accounting firm in midtown Manhattan, Henriques wrote. He later moved his operation to a small office in the city’s financial district.

Madoff’s market-making firm, which specialized in pairing buyers and sellers of stocks, was a pioneer in electronic trading at the dawn of the computer age.

A 1992 account in The Times noted Madoff’s midtown Manhattan office was filled with modern art and 50 traders sitting at their computer terminals quietly monitoring transactions.

By then, Madoff’s market-making business had become a thorn in the side of the New York Stock Exchange, whose old-fashioned trading floor model was increasingly coming under attack by computer-based upstarts.

“I spend a lot of time defending myself, unnecessarily,” Madoff told The Times then. “The NYSE should spend as much time improving their own systems and quality of markets as they do giving out misinformation about their competitors.”

His prestige in the industry helped him climb to the chairmanship of the Nasdaq stock market, then a scrappy, all-electronic rival that was seen as an incubator for smaller companies.

He served on the board of governors of the National Assn. of Securities Dealers, the financial industry-funded watchdog that later became the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, or Finra.

“These were really good covers for a massive Ponzi scheme,” said Sylla, the financial historian. “There was a legitimate business associated with his name. People in the community seemed to respect him enough to give him an honorary chairmanship.”

But separate from his market-making business, Madoff started an investment advisory business. Instead of pairing buyers and sellers, he began to take clients’ money to invest.

Madoff’s investment business first caught the eye of the SEC in 1992. That year, the agency heard of an unregistered operation that offered supposedly “100% safe” investments with consistently high returns, according to a report by the SEC’s inspector general. The agency suspected it was a Ponzi scheme and learned its investments were entirely placed through Madoff.

Over the next 16 years, the SEC received five more substantive complaints raising red flags, including detailed reports by a rival investment manager from Boston named Harry Markopolos. One of his complaints, in 2005, was titled: “The World’s Largest Hedge Fund Is a Fraud.”

Madoff nonetheless escaped three SEC examinations and two investigations. The agency failed to take action after the agency caught Madoff in lies and misrepresentations, according to the SEC’s inspector general. SEC staff also failed to even verify Madoff’s trading records — a misstep that “astonished” Madoff, he would later say.

In his own interview with the SEC’s inspector general in June 2009, Madoff said he wished regulators had stopped him years earlier. He expressed remorse for the damage he inflicted on his investors, and Wall Street.

“The thing I feel worst about besides the people losing money is that I set the industry back,” Madoff said. “It’s a tragedy. It’s a nightmare.”

By early 2014, a court-appointed trustee overseeing Madoff’s wreckage counted more than 16,500 claims filed by Madoff victims. The majority were denied because many victims invested in Madoff through a third party.

In the end, not all of the investors’ money was lost. Of the $20 billion in estimated cash losses in Madoff’s fraud, the trustee, Irving Picard, had secured well more than half through recoveries and settlements as of 2018.

David Sheehan, Picard’s lead attorney in the case, said the magnitude of Madoff’s scheme may serve as a cautionary tale.

“There couldn’t have been a more devastating story for all of the victims than what Mr. Madoff did to them,” Sheehan said. “And yet at the same time, one wonders whether or not today, after people have had the opportunity to absorb the massive nature of his fraud, whether they are thinking soundly enough to protect themselves from being part of something like that again.”

Tangel is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.