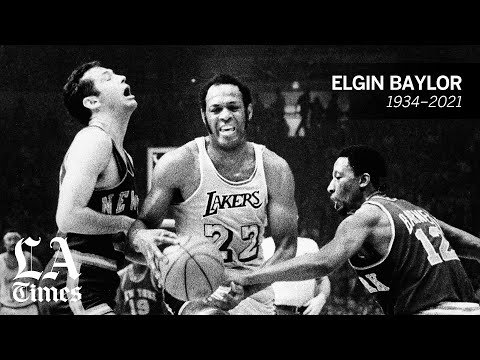

Elgin Baylor, Lakers legend and former Clippers executive, dies at 86

Elgin Baylor, the Los Angeles Lakers’ first superstar and one of the greatest players in NBA history, died Monday, the Lakers announced. He was 86.

For the Lakers, Elgin Baylor came along at precisely the right time.

Still in Minneapolis, where the George Mikan glory years were well past, they used the No. 1 overall pick in the 1958 draft to get Baylor, after owner Bob Short persuaded him to skip his senior year at Seattle University. The Lakers had just finished a 19-53 season with a team that was old, slow and drawing poorly at the gate. Baylor was viewed as the team’s best hope for survival.

“If he had turned me down then, I would have been out of business.” Short told The Times in 1971. “The club would have gone bankrupt.”

With Baylor earning rookie-of-the-year honors in 1958-59, the Lakers went from last in their division to the Finals. After one more season in Minneapolis, Short moved the club to Los Angeles, hoping to cash in on some of the excitement generated by the recently arrived Dodgers. The city, though, seemed largely unimpressed.

But at least the team had a selling point in Baylor, a superstar in the making.

A fixture on the L.A. basketball scene as a player, coach and longtime Clippers executive, Baylor died Monday of natural causes in Los Angeles, the Lakers announced on Twitter. He was 86.

“Elgin was THE superstar of his era — his many accolades speak to that,” Lakers President Jeanie Buss tweeted.

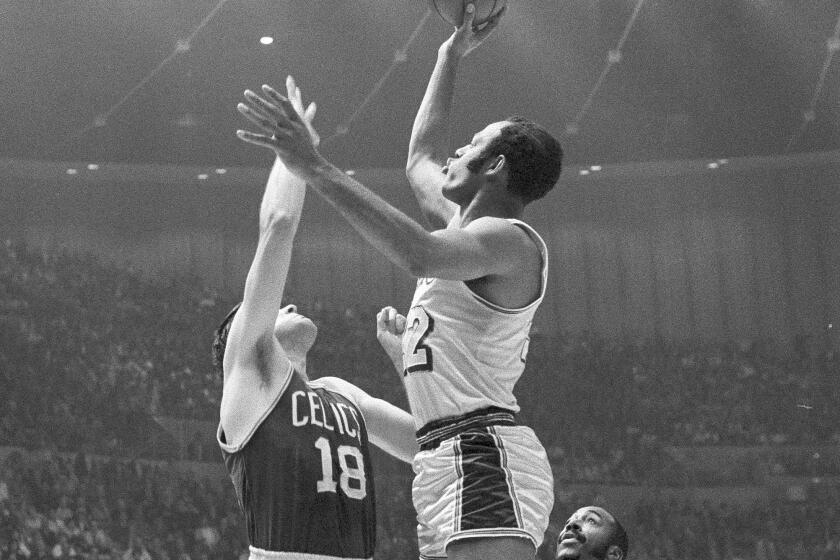

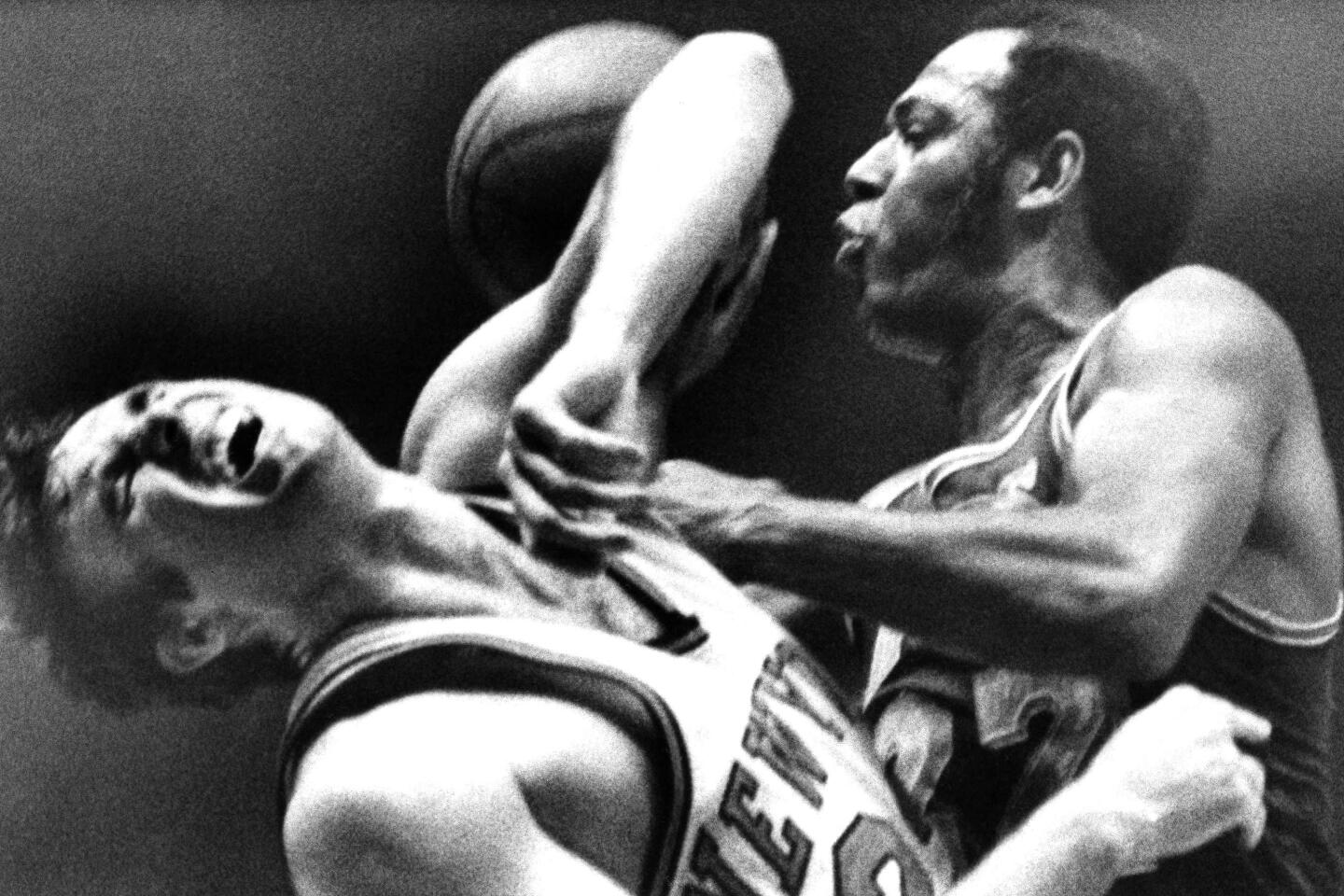

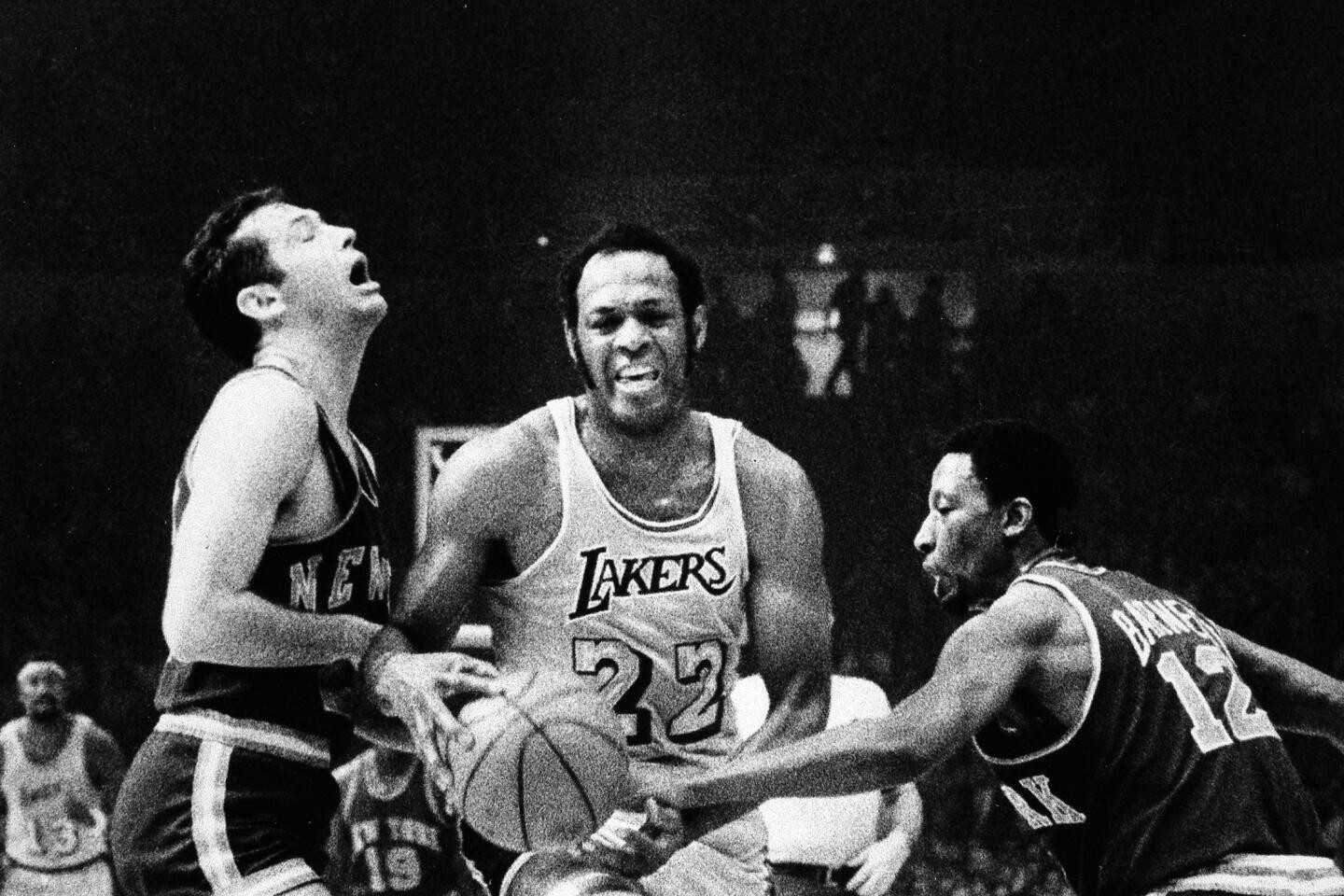

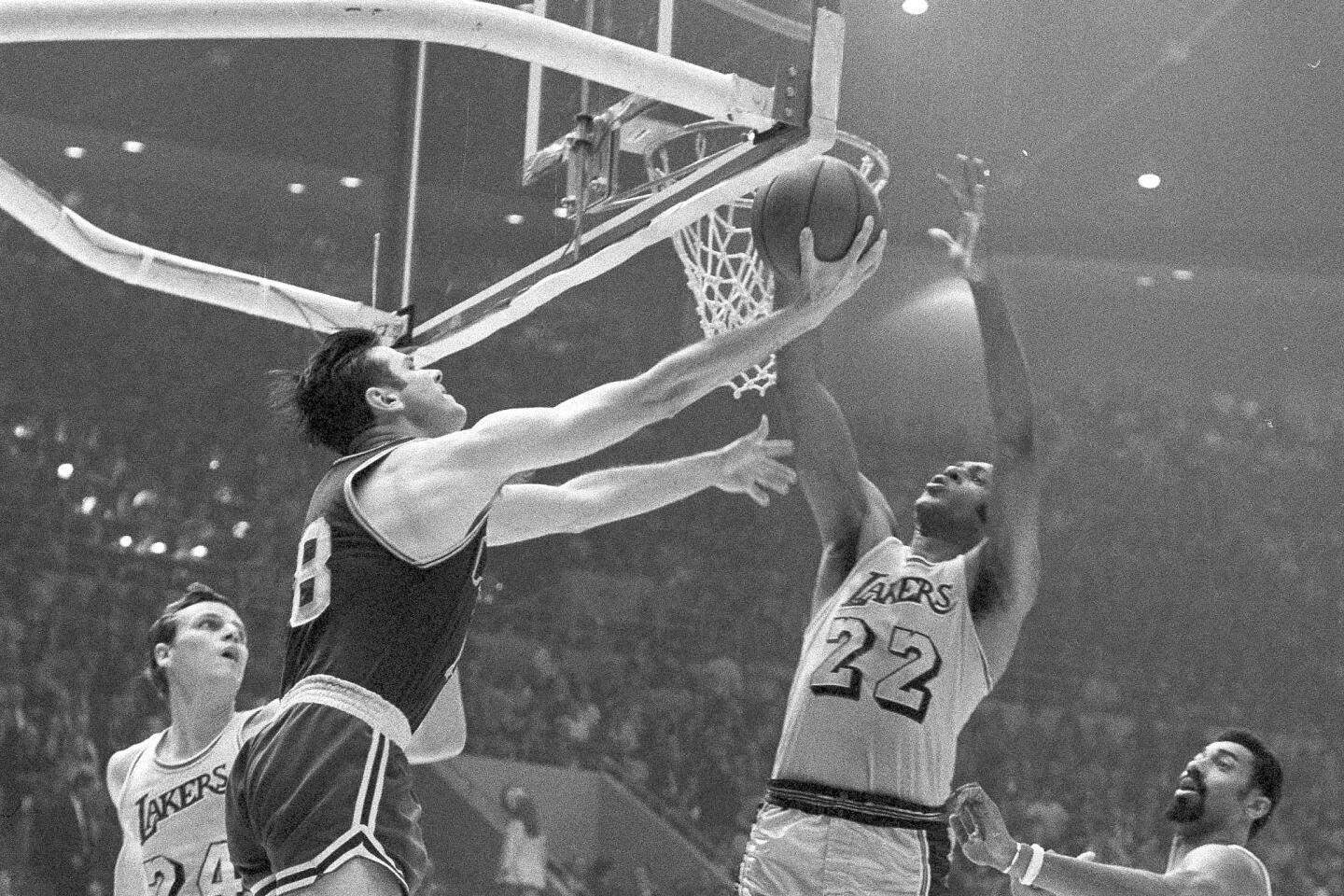

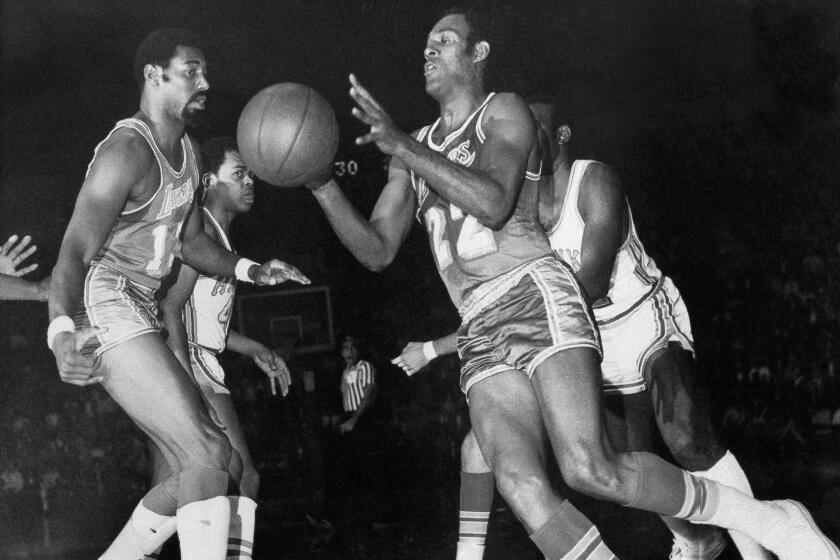

An undersized power forward at 6 feet 5 inches, Baylor dazzled with a variety of athletic moves that often left defenders flat-footed as he sailed by for one of his signature running bank shots or pulled up for a hanging jump shot.

Richie Guerin of the New York Knicks once griped, “Elgin Baylor has either got three hands or two basketballs out there. It’s like guarding a flood.”

Observed Oscar Robertson, a contemporary of Baylor’s and himself no stranger to NBA stardom, “As a shooter, as a dribbler, Elgin Baylor had no match. The greatest game I ever saw was a Los Angeles playoff game in Boston when the Celtics double-teamed Elgin and Jerry West, and Elgin still scored about 60 points.” Sixty-one, actually.

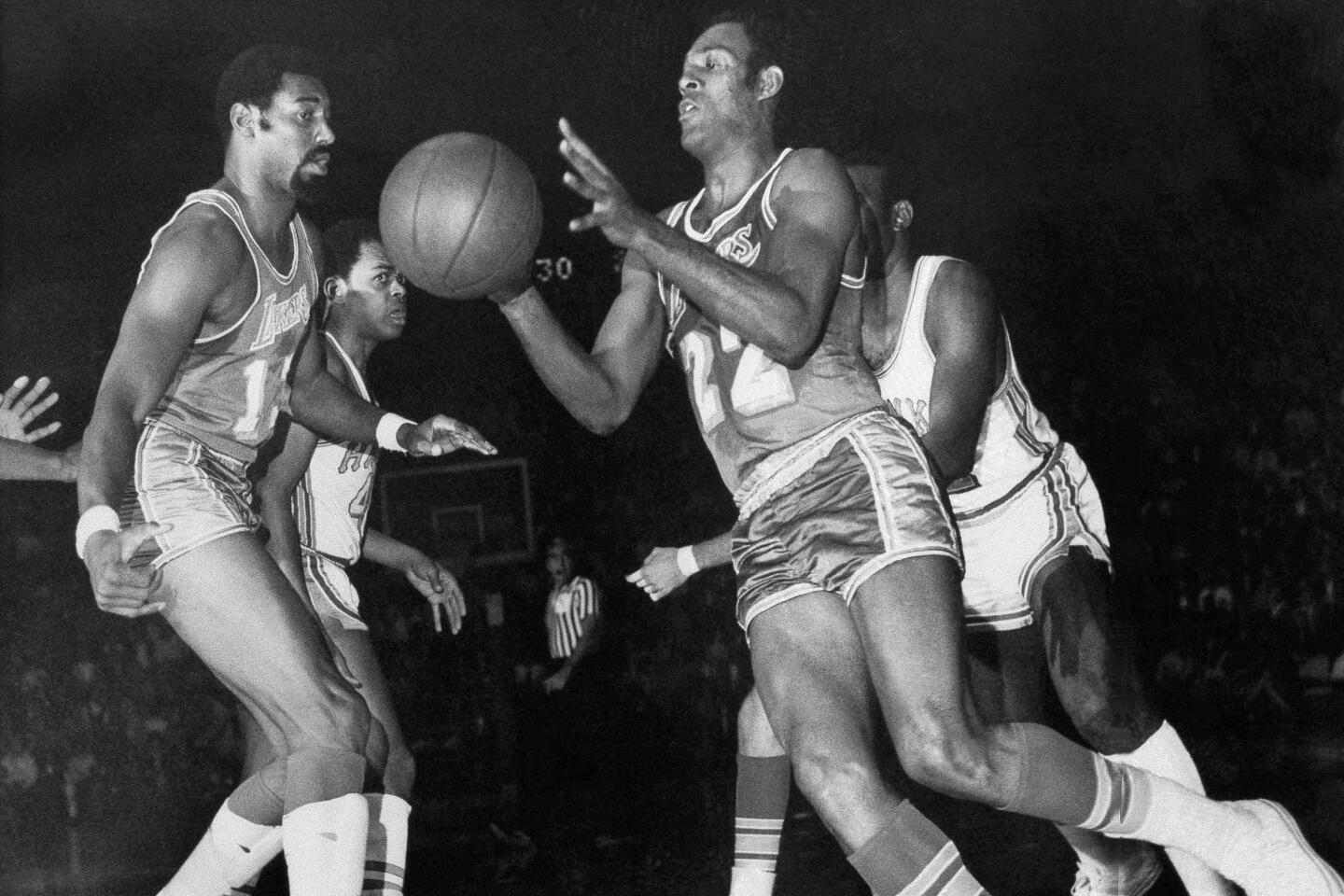

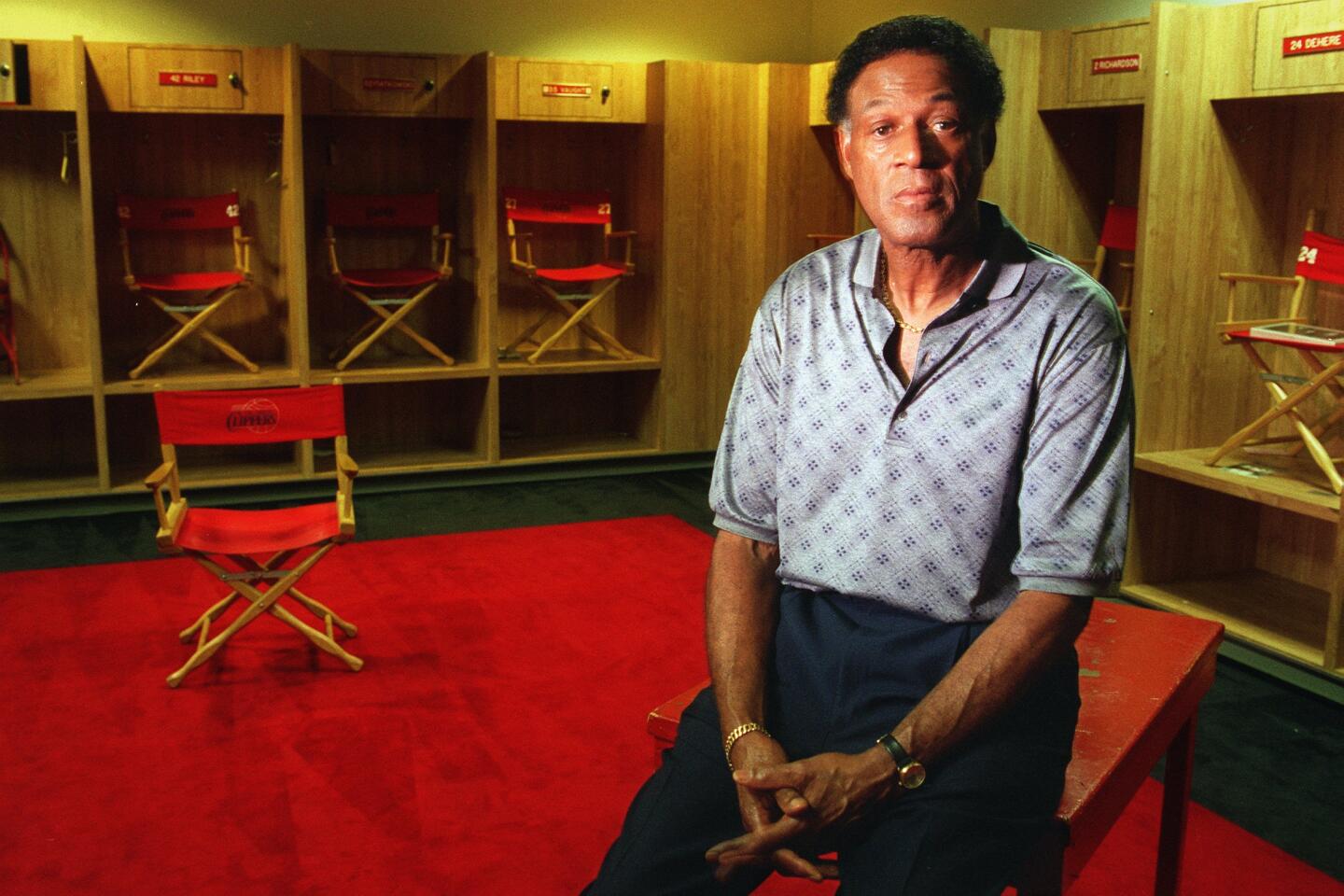

A look at the life and playing days of Lakers Hall of Famer Elgin Baylor, who would become an executive with the Clippers.

A 10-time All-NBA first team selection and 11-time All-Star, Baylor was elected to the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in 1977. Although primarily a scorer, he was nonetheless a complete player, finishing his career with 23,149 points, 3,650 assists and 11,463 rebounds in 846 games, all with the Lakers in Minneapolis and Los Angeles.

He scored a then-record 71 points against the Knicks during a regular-season game in 1960, and his 61-point game against the Celtics in Game 5 in 1962 still stands as an NBA Finals individual record.

The duo of Elgin Baylor and Jerry West made the Los Angeles Lakers a power in the NBA. West recalls his relationship with Baylor, who died Monday.

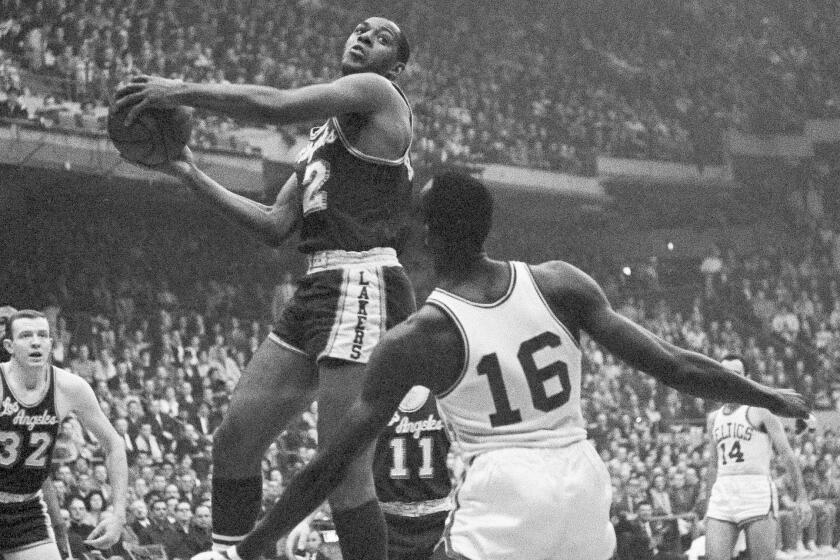

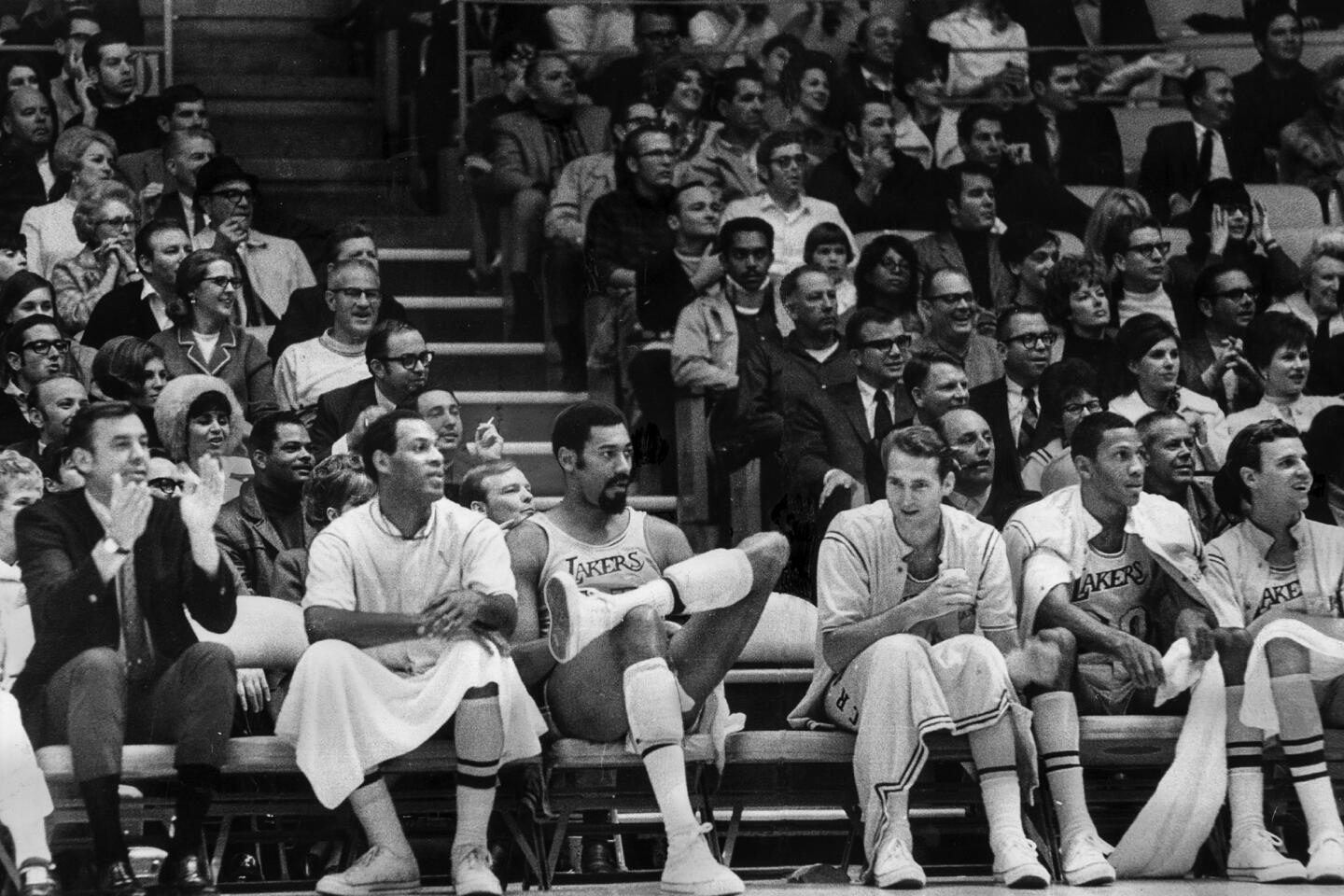

Baylor and Jerry West, then a promising rookie guard from West Virginia, meshed beautifully and in only their second season in Los Angeles, the Lakers were back in the Finals. During Baylor’s career, the Lakers were beaten seven times in the Finals by the Celtics and once by the Knicks, leaving one of the NBA’s greatest stars without a championship ring. Worse, in the eyes of many, Baylor, plagued by bad knees and trying to come back from surgery for a torn Achilles tendon, retired nine games into the 1971-72 season, the season the Lakers finally went all the way, beating the Knicks for L.A.’s first NBA championship.

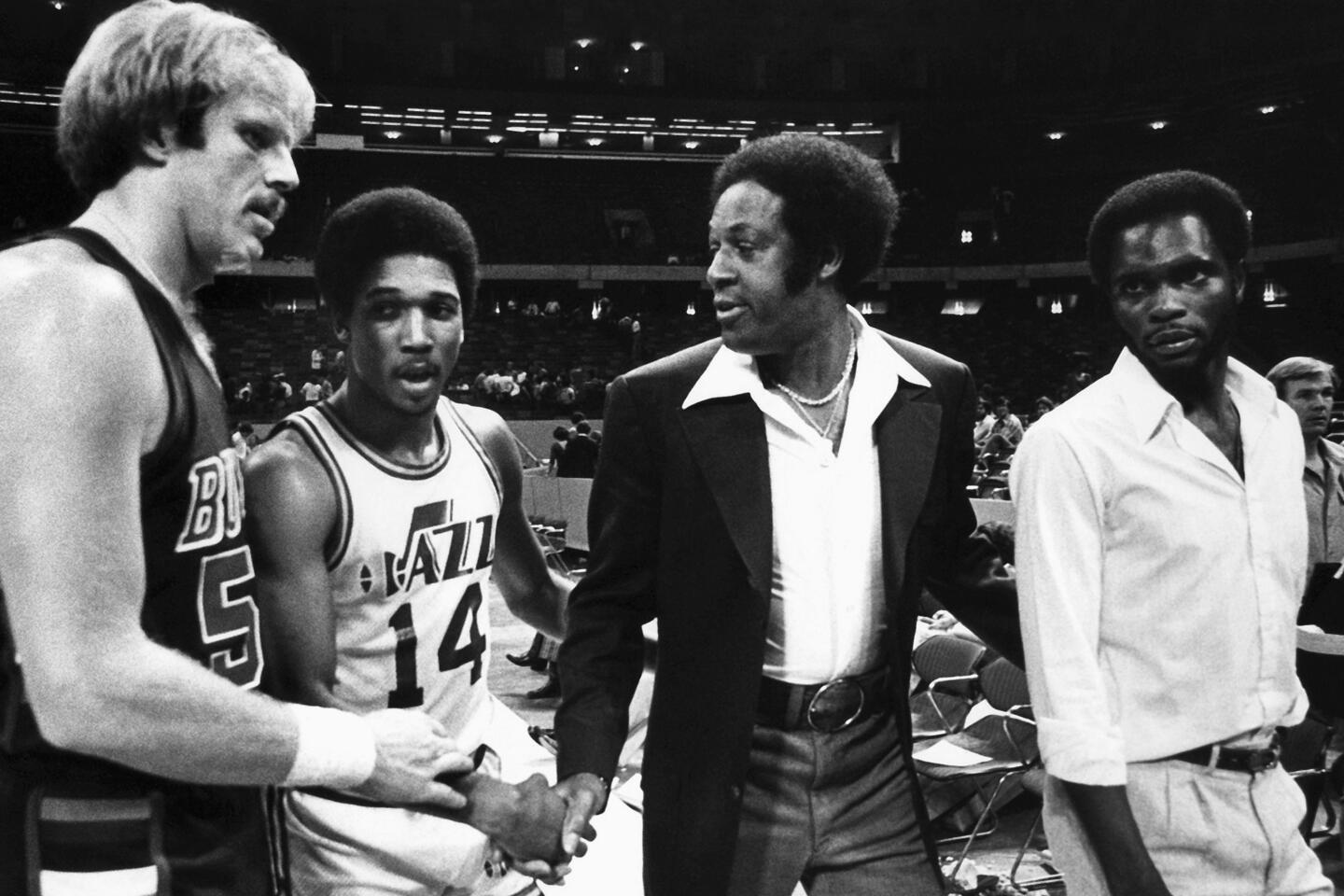

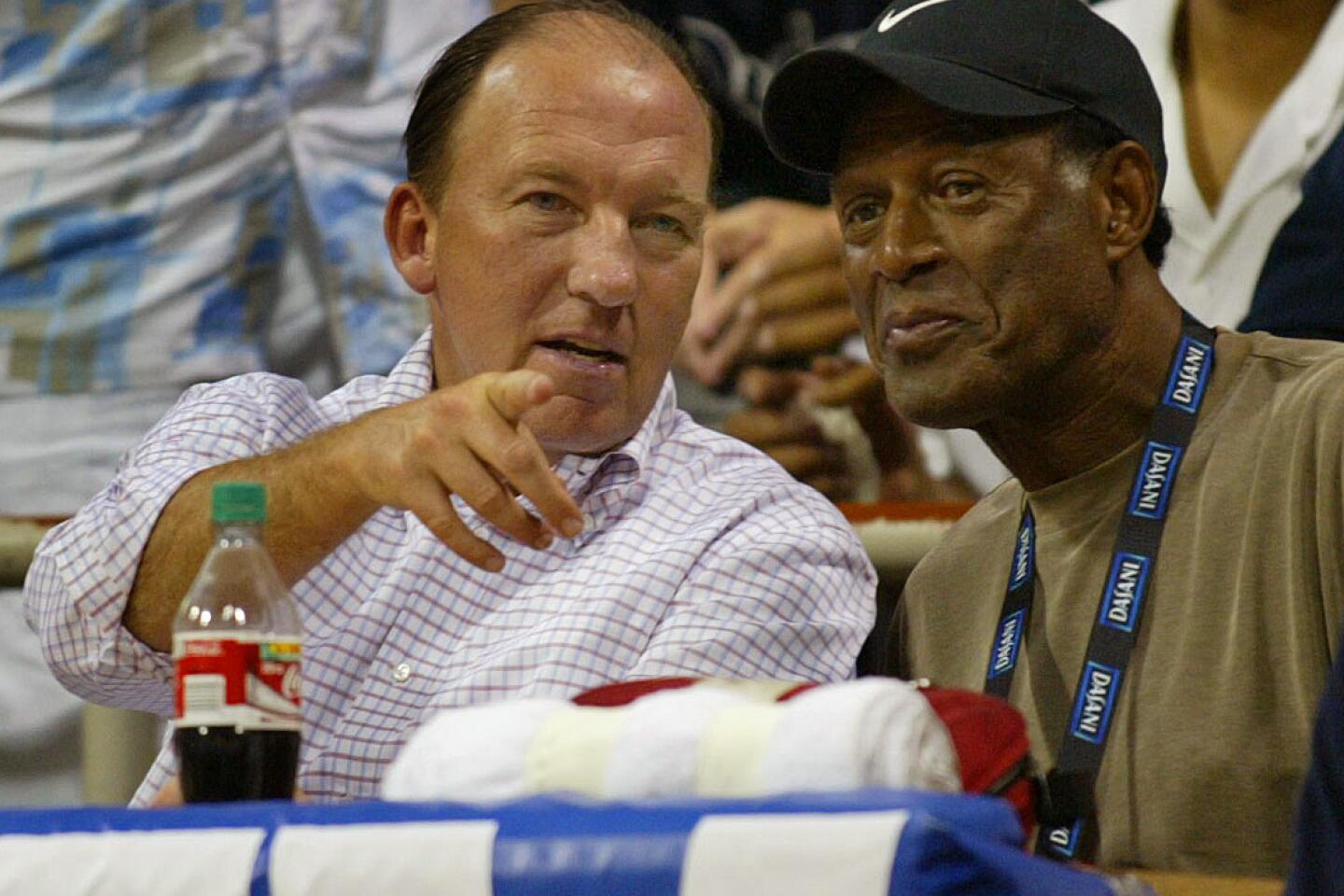

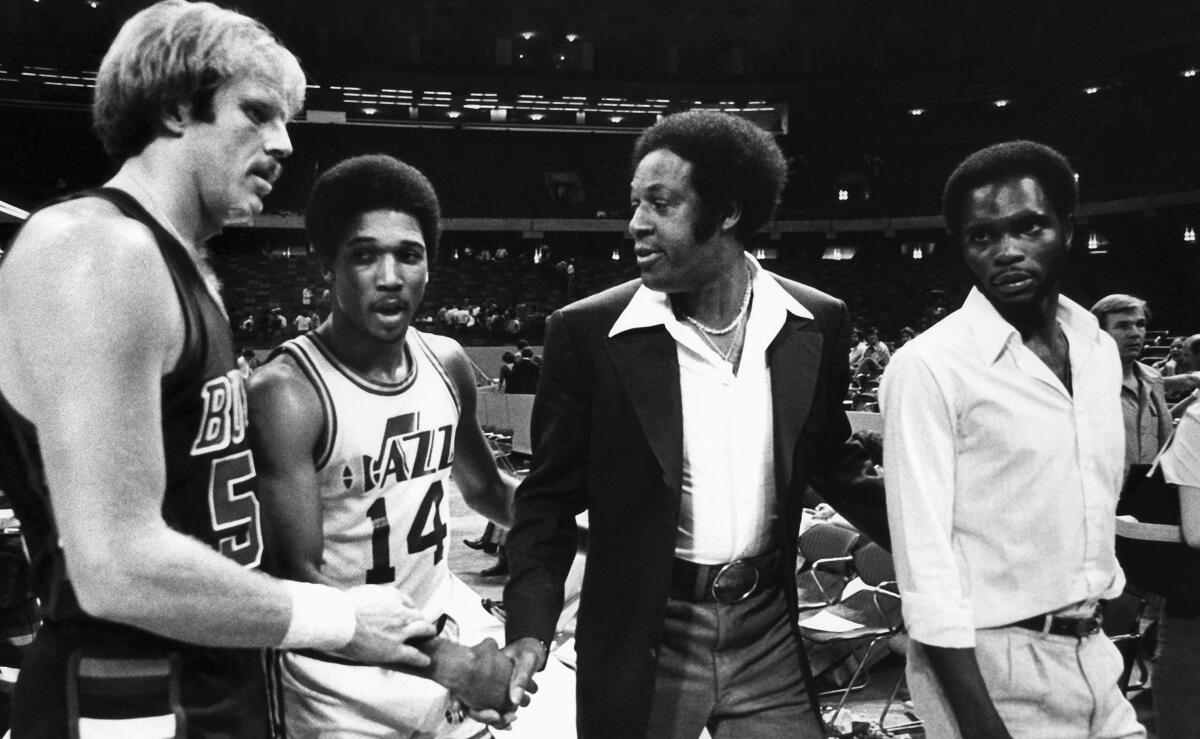

Baylor’s prowess on the court didn’t quite carry over to his duties as general manager and vice president of basketball operations with the Clippers. He was named NBA executive of the year in 2006, after the team had advanced to the second round in one of its then rare playoff appearances, but during his 22 years with the team, the Clippers had a .349 winning average — 619 games won, 1,153 lost — made the playoffs only four times and ran through 10 head coaches.

While West, Baylor’s former teammate, was taking the Lakers to unprecedented success as their general manager, the Clippers struggled for mediocrity, and although Baylor’s Clippers tenure ranked among the longest for an NBA general manager, it ended acrimoniously in the fall of 2008, when the 74-year-old Baylor was either fired (his version) or resigned (the Clippers’ version).

Amid accusations of racism, age discrimination and a hostile working environment against owner Donald Sterling and the Clippers, Baylor sued the club for nearly $2 million in 2009. Baylor, who accused Sterling of having a “plantation mentality,” withdrew the racism claim as the case went to trial in the spring of 2011 and a jury of seven men and five women eventually rejected Baylor’s other claims, finding in favor of the Clippers.

Years later, when the NBA banned Sterling for his racist comments about Black players, former Laker great Magic Johnson said it appeared Baylor was right about Sterling.

“Everything that he said is coming to light today,” Johnson told The Times in 2014.

Baylor always felt that comparison of the rich and successful Lakers and the always-struggling Clippers was not quite fair. “It’s like in a poker game,” he said. “We start with the same stakes, then see how we end up. Don’t start someone off with a million dollars and give me a thousand dollars.”

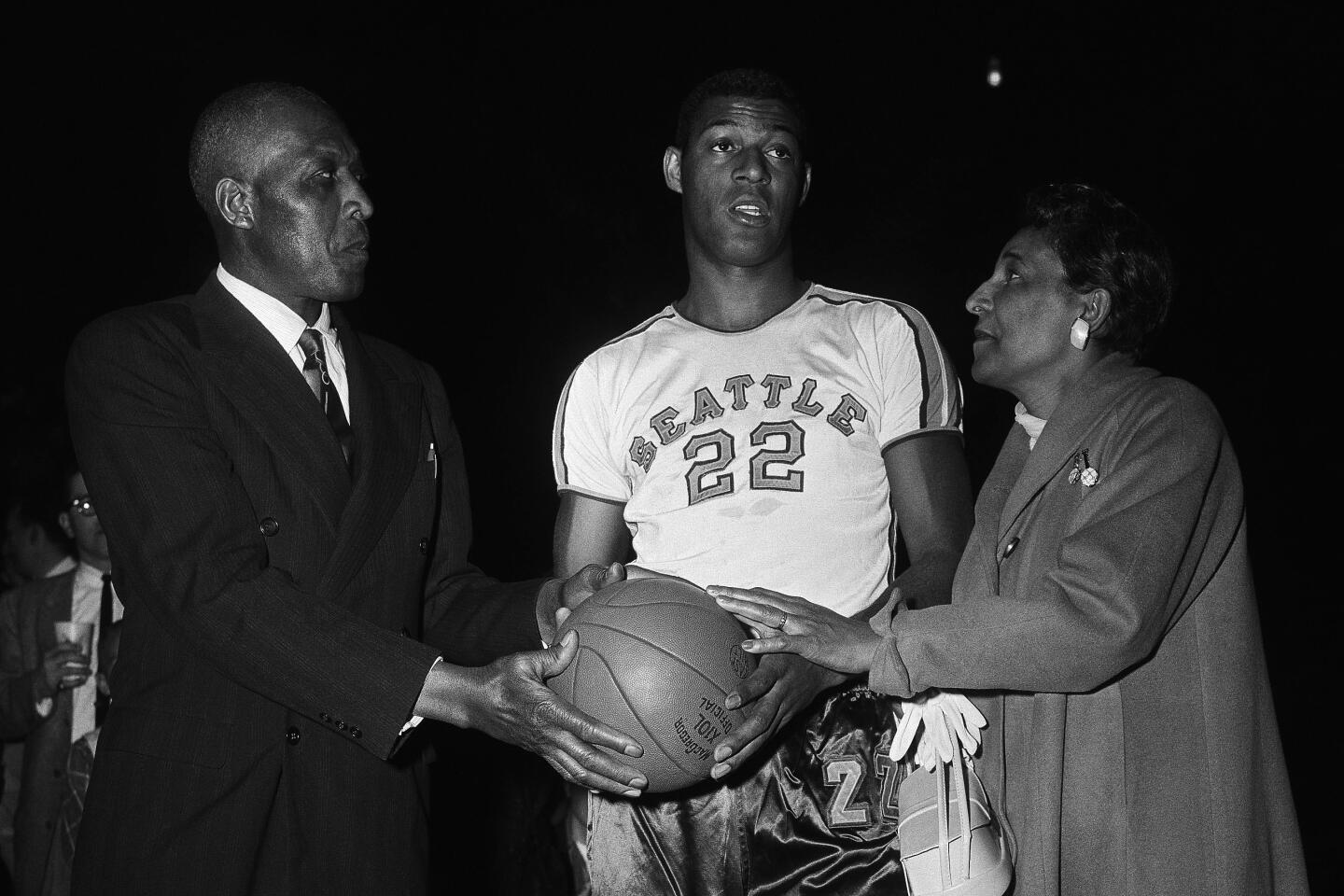

Baylor was born Sept. 16, 1934, in Washington, D.C., and later told how his father, John, consulted his pocket watch to mark the time of birth, noted that the watch was an Elgin and thought that would be a fine name for his newborn son. Unlike so many athletes, Baylor did not grow up playing the game that made him famous. D.C. playgrounds were closed to Black athletes at the time, so Baylor didn’t find basketball until he went to high school, where he became a three-time All-City player.

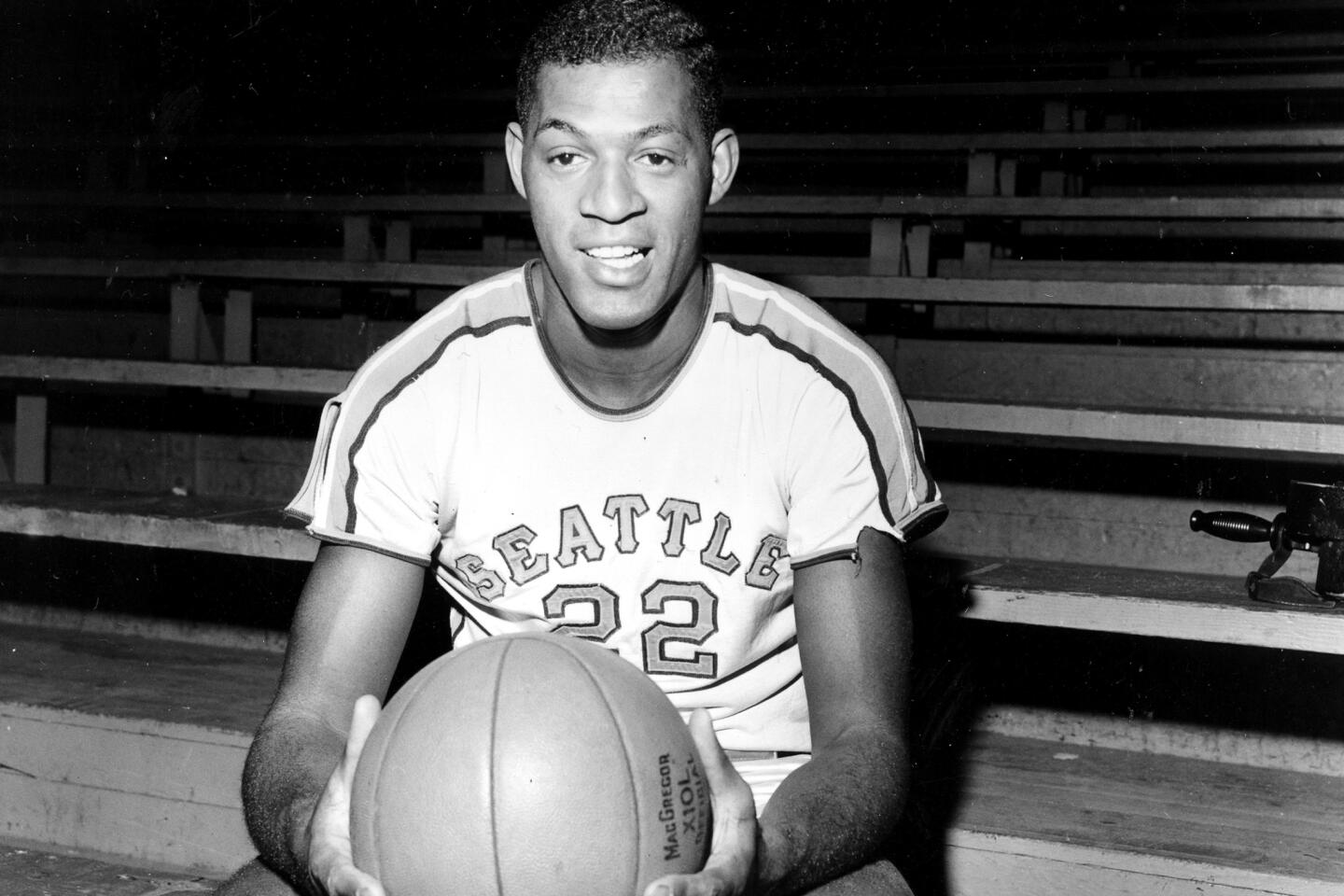

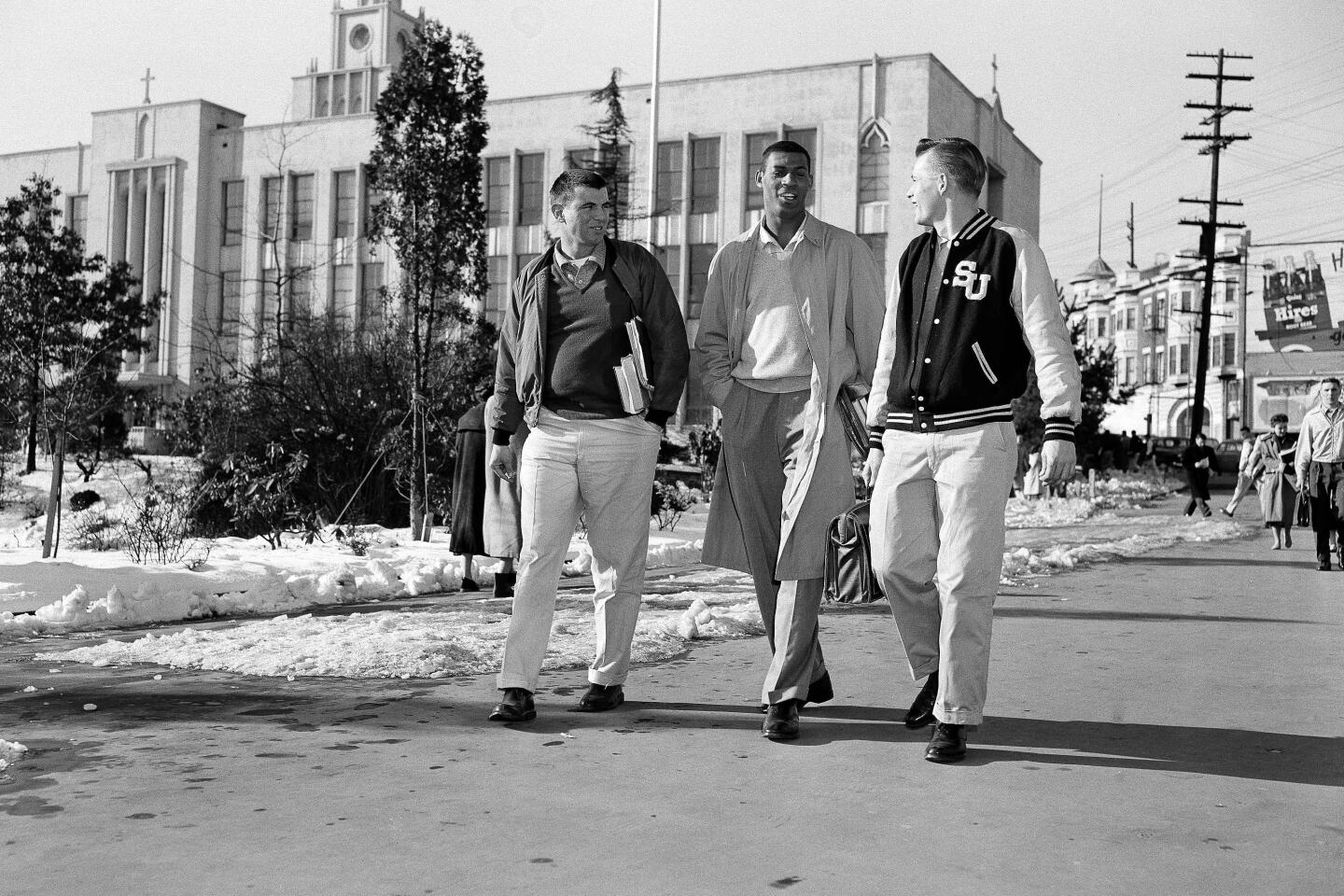

After one year at the College of Idaho, Baylor enrolled at Seattle University and sat out a season, as then required of a transferring athlete. He followed with two productive seasons for the Chieftains, earning second-team All-American honors in the first and first-team All-American in the second and taking the team to the Final Four in the NCAA tournament in 1958. The team ultimately lost to Kentucky in the championship game.

Elgin Baylor never received the level of adulation from Lakers fans that other team legends received. He was a pioneer in a town with a short memory, Bill Plaschke writes.

Having sat out a season, Baylor was eligible for the NBA draft as a junior. Short offered to pay him $20,000, a handsome sum at the time, to play for the Lakers. Though on his way to a remarkable career, he was initially skeptical that he was ready for the pros.

“When I went to training camp and saw all those big guys, I wondered if I really could make it,” he once recalled. “But right after the first practice, I could sense that I was as good as they were.”

Better, in fact, combining body strength and fluid moves with a wicked head fake to draw opponents off balance. He averaged 24.9 points and 15 rebounds in his first season. He had a single-game high of 55 points.

So important to the Lakers was Baylor that when, after his rookie season he was sent to Ft. Sam Houston in Texas for active duty with his Army Reserve unit, the club moved its training camp to San Antonio so he wouldn’t miss preseason workouts.

Again in 1962, where Baylor went, the Lakers went. Recalled to active duty for part of the 1961-62 season, Baylor received permission from the NBA to play regular-season games whenever he could get weekend leave. When they made the playoffs, the Lakers set up camp in Tacoma, Wash., where Baylor was serving at Madigan General Hospital, for three days. They went all the way to the Finals that spring but couldn’t beat Bill Russell and the Celtics, another note in a recurring theme.

As good as he was on the court, Baylor was equally good with the language, keeping the locker room loose with discussions, arguments, observations, jokes and his puckish sense of humor. He dubbed West “Zeke from Cabin Creek” and once answered a phone call from legendary Times sports columnist Jim Murray with, “Sherwood Forest, Robin Hood speaking.”

He had his serious side, though, and bristled at the racial slights he suffered.

When the Lakers checked into a hotel in Charleston, W.Va., for a neutral-site game against the Cincinnati Royals, the desk clerk said that the white players could register but the Black players would have to find lodging elsewhere. So the entire team went elsewhere and Baylor refused to play in front of the hometown fans that night.

“I’m a human being,” Baylor said. “I’m not an animal put in a cage and let out for the show.”

Baylor’s anger grew when the city’s mayor demanded he apologize to the city for sitting out the game.

“He was a very proud man,” said the late Rod Hundley, who had played at West Virginia University and understood what Baylor and the league’s other Black players had to struggle against. Hundley would go on to become Baylor’s teammate with the Lakers.

It was Baylor, too, who backed down Bob Short in a labor dispute. Looking for a pension plan, NBA players threatened to strike before the 1964 All-Star game. Celtics stars Bob Cousy and Tommy Heinsohn were the organizers, but Short came pounding on the locker room door, demanding to see Baylor and West. Baylor came out and spoke with the team owner. After the conversation, Short went back to the other owners and they agreed to accept the players’ demands.

The beginning of the end occurred April 3, 1965. It was Game 1 of the Western Division finals against the Baltimore Bullets and Baylor pulled up for one of his deadly jump shots, then came down writhing in pain. He had separated the upper part of his kneecap. Doctors later removed part of the kneecap, along with tendons and ligaments, and scraped out loose pieces of calcium.

Baylor was back for the next season but was a mere shadow of his former self, averaging 16.6 points and, for the first time, failing to make first-team All-NBA.

“It was like watching Citation [1948 Triple Crown winner] run on sprained legs,” longtime Lakers announcer Chick Hearn later said.

Baylor pushed himself hard after that disappointing season and was back among the NBA’s elite, averaging at least 24 points in the next four seasons, but the torn Achilles tendon limited him to two games in the 1970-71 season. And after vowing to come back in ’71-72, he realized that he could no longer depend on his old skills and decided to retire.

“I hoped to end my career after one last successful season,” he said at the time. “Out of fairness to the fans, to the Lakers and to myself, I’ve always wanted to perform on the court up to … the standards I have established throughout my career. I do not want to prolong my career to the time when I can’t maintain those standards.”

The day after Baylor’s retirement, the Lakers posted the first of 33 consecutive victories, a winning streak unmatched in pro sports, as they marched to their first championship in Los Angeles.

In 1983 his jersey number — No. 22 — was retired and in 2018, a bronze statue of Baylor was installed in front of Staples Center, alongside the statues of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Jerry West, Magic Johnson, Shaquille O’Neal and the person who helped bring them all to life — Hearn.

Baylor is survived by his second wife, Elaine; their daughter, Krystle; and a son, Alan, and daughter, Alison, from a previous marriage.

Mike Kupper is a former Times staff writer. Times staff writer Steve Marble contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.