Siegfried Fischbacher, of Siegfried & Roy big-cat illusionist team, dies

German news agency dpa is reporting that illusionist Siegfried Fischbacher, the surviving member of the duo Siegfried & Roy, has died in Las Vegas.

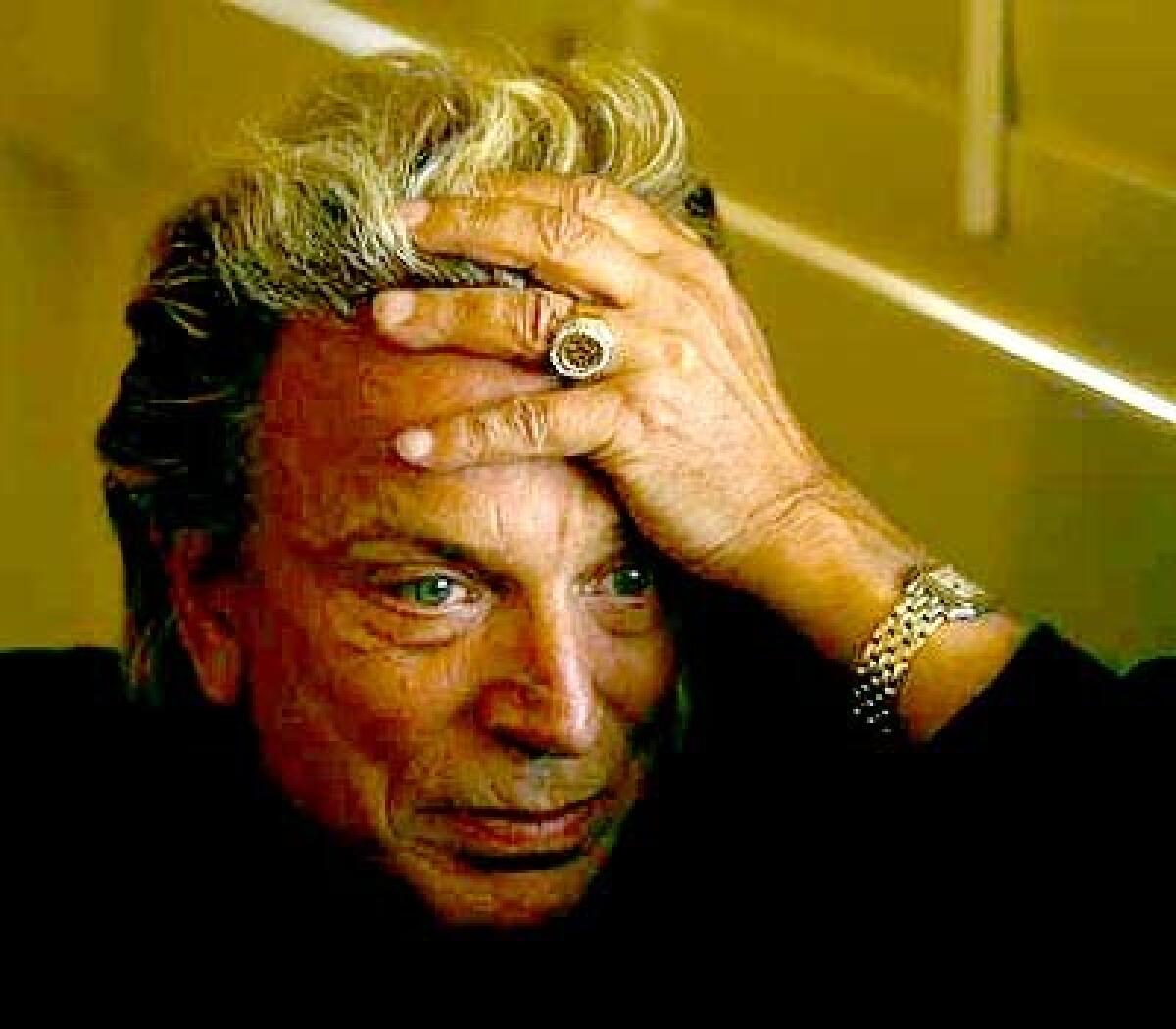

They were the Tiger Kings of Las Vegas before “Tiger King” was a thing. Now, Siegfried Fischbacher, the blond half of the wildly successful big-cat illusionist duo Siegfried & Roy, has died of pancreatic cancer at his home in the desert. He was 81.

The magician’s death late Wednesday comes less than a year after his longtime performing partner, Roy Horn, died from complications of COVID-19.

Born June 13, 1939, in Rosenheim, Germany, Fischbacher was drawn to magic from a young age — he was 8 when he got his first magic book, which he saw in a merchant’s window, according to his official website. He was struggling at the time with a strict father affected by the trauma of World War II.

“I thought that if I could have this magic book, then I could solve the problems at home,” he told The Times in 1999. “When I learned my first trick and showed it to my father, that was the first time in my life he noticed me. So I think magic became a life, and I grew to realize that life is magic.”

The illusionist, whose animal act partner is sidelined by stroke and injury, lives on hope.

He was also inspired by the German illusionist Kalanag, who died in 1963. “It wasn’t so much his illusions that thrilled me. It was his personality and the glamor of the elaborate stage sets,” Fischbacher said on his website.

Fischbacher wound up leaving home at 17, first becoming a dishwasher at a resort in Italy and then signing on as a steward on a cruise ship. Eventually, he began doing his tricks for passengers instead of just for the crew. The act grew in popularity, with props and a second show added.

“Now I had animals, props, lighting cues, music. It was too much for one person, so I decided to ask a steward — anyone would do — to help me,” Fischbacher said on the Siegfried & Roy website. Hustling for an extra hand was how he met Horn, his future performing partner, who was working as a waiter. Horn’s interest in exotic animals had begun in boyhood.

Giving feedback after that first show, Horn asked Fischbacher, “If you can make a rabbit and a dove appear, could you do the same with a cheetah?”

It wasn’t a bad idea — on the next cruise, Horn showed Fishbacher the live cheetah he’d smuggled on board, and the two wound up working the cat into their act. It got them fired, but also resulted in an offer to work on the cruise line’s Caribbean journeys.

The two became partners, with Horn as the dark-haired match to Fischbacher’s bleached-blond presence. Working in the confines of a ship forced Fischbacher to plumb the edges of his imagination as the act progressed. Horn was the beastmaster, wrangling Chico the cheetah. In one illusion, Fischbacher disappeared in the middle of the act and reappeared as the cat.

“[W]hen Roy showed me that cheetah, it made all the difference,” Fischbacher told Vanity Fair. “I can tell you this: When I disappear from the lounge of that ship in the middle of the ocean, and reappear as a cheetah, this is better than pulling rabbits out of a hat.”

The cruise act became a struggling European nightclub act, and they added tigers to the mix. In 1966, they were noticed by Princess Grace of Monaco, and the next year were invited to come to Las Vegas to be part of the Folies Bergere review at the Tropicana. They eventually became naturalized American citizens.

“When we first came to Las Vegas, our welcome was: ‘You’re a magician; we have to tell you, magic doesn’t work in this town,’” Fischbacher told The Times in 1995.

There are those who say vaudeville died in the mid-1930s; others, such as magician Harry Blackstone Jr., believe that it was murdered.

Fischbacher was invited to become a member of Hollywood’s Magic Castle in the 1970s, befriended by the German widow of one of the private club’s co-founders. The club became a second home.

He said being honored by the Magic Castle’s Academy of Magical Arts helped him move up the Las Vegas ladder. “The most difficult thing was to create a demand for what we are doing.”

The demand was there: They became headliners at the Stardust in 1978. In the 1980s, they had a six-and-a-half-year run at the Frontier Hotel. There was a world tour, and a five-year run at the Golden Nugget on the Strip. In 1990 they signed a $57.5-million, five-year contract with the Mirage on the Strip. In 1999 they were honored with a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame and in 2001 they signed a “contract for life” at the Mirage.

There they performed their over-the-top illusion spectacle in the custom-designed, 1,504-seat Siegfried & Roy Theater, entertaining 700,000 people a year. Over 44 years, according to their manager, Bernie Yuman, the duo performed more than 30,000 live shows to close to 50 million people.

Eight years after debuting at the Mirage, Forbes magazine reported that Siegfried & Roy were the highest-paid entertainers in Las Vegas history, earning an estimated $58 million in 1996-97 (with an estimated net worth of more than $100 million).

Steve Wynn, who owned the Mirage from its opening in 1989 until 1997, once called Siegfried & Roy “the entertainment cornerstone of Las Vegas, and the most important single act in town, comparable only to Frank Sinatra.”

Actor-politician Arnold Schwarzenegger, who emigrated from Austria to the U.S., once called the men “the greatest immigration story I know: two guys who came over to this country, starting with nothing, who made their dream come true.”

The elaborate Siegfried & Roy show featured complex stagecraft, liquid smoke, lasers, dozens of dancers and more than 30 exotic cats. In the early 1990s, the finale to their sold-out shows featured Horn “magically” appearing on the back of a white tiger sitting on a mirrored disco ball; his partner and a dozen other animals then joined them as they all levitated skyward.

Roy Horn, the dark-haired half of Siegfried & Roy, raised the white tigers and other animals in the duo’s extravagant shows that were one of the biggest draws on the Las Vegas Strip.

It wasn’t all perfect. Fischbacher was a worrier and became addicted to Valium in the 1970s, and Horn considered spinning off his own act, according to the Washington Post.

The duo, who shared a home for decades — the eight-acre West Las Vegas compound dubbed the “Jungle Palace” — but didn’t talk about their personal life, lived with the animals who appeared in their act. Horn told People magazine in 1993, “we live in completely different parts of the house and go on vacations alone.”

Fischbacher spoke with Vanity Fair in 1999 about Horn’s relationship with the tigers, which they bred on their property. The latter slept with cubs until they were a year old. “I respect it. I am awed by it. I enjoy the whole thing. I am grateful that Roy makes me a part of it,” Fischbacher said. At one point there were more than 60 tigers on the premises.

Their Vegas run screeched to a halt in 2003 after Horn was critically injured by a white tiger named Mantecore, who sunk his teeth into his handler’s neck during a performance and dragged him offstage. Horn suffered a stroke, nearly bled to death and never fully recovered.

The two never blamed the tiger, who died a natural death in 2014. And Fischbacher swore the show would not go on without Horn.

There was one more performance, though, with Mantecore, in February 2009: The two performed a signature illusion at a charity event at the Bellagio. Horn was 75 when he died in 2020.

“Do you know what the secret to Siegfried & Roy was?” a tearful Fischbacher told The Times in 2003, following Horn’s accident. “It was the love — the audience knew it, felt it.”

Former Times staff writer Dennis McLellan contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.