Homicides down after tougher gun laws adopted abroad

Twelve days after the worst mass murder in Australian history, when 35 people were shot to death at Tasmania state’s Port Arthur tourist mecca in 1996, the government issued sweeping reforms of the country’s gun laws. There hasn’t been a mass shooting since, and suicides, deaths by firearms and robberies at gunpoint have plummeted.

The results of toughened gun rules in Britain after the massacre in the Scottish town of Dunblane that same year weren’t so immediate or impressive. Gun crimes continued to rise until 2003, and despite a steady downturn since then, a dozen people were killed two years ago in Cumbria by a man using legally registered weapons.

Mass murders by gun-wielding maniacs aren’t unique to the United States, although crime statistics show the tragedies to be far more prevalent in a nation that gained its independence by musket and proudly brandishes a constitutional guarantee of a right to bear arms. As the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence attests on its website, in a single year guns killed 17 in Finland, 35 in Australia, 39 in Britain, 60 in Spain, 194 in Germany, 200 in Canada and 9,484 in the United States.

“We are the only developed nation in the world that allows people such easy access to even the most dangerous weapons,” said Adam Winkler, a UCLA law professor and author of “Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America.”

“There are other countries where you can own an assault rifle, such as Switzerland, but they impose strict laws on who can have them and when they can carry them.”

Even idyllic Switzerland hasn’t been immune from mass-casualty gun violence. In 2001, a disgruntled public official in the northern city of Zug killed 14 people at the regional parliament before taking his own life. Swiss voters last year defeated a referendum that would have required all weapons registered to members of its citizen militia to be secured in military depots.

Most foreign countries that have endured gun violence have reacted with tighter restrictions on which weapons can be privately owned, who can obtain them, how they can be licensed and stored and what penalties are imposed on violators. But a review of mass killings abroad over the last two decades reveals a contradictory picture of the effectiveness of strict controls in an age of Internet-based arms trading and global criminal networks.

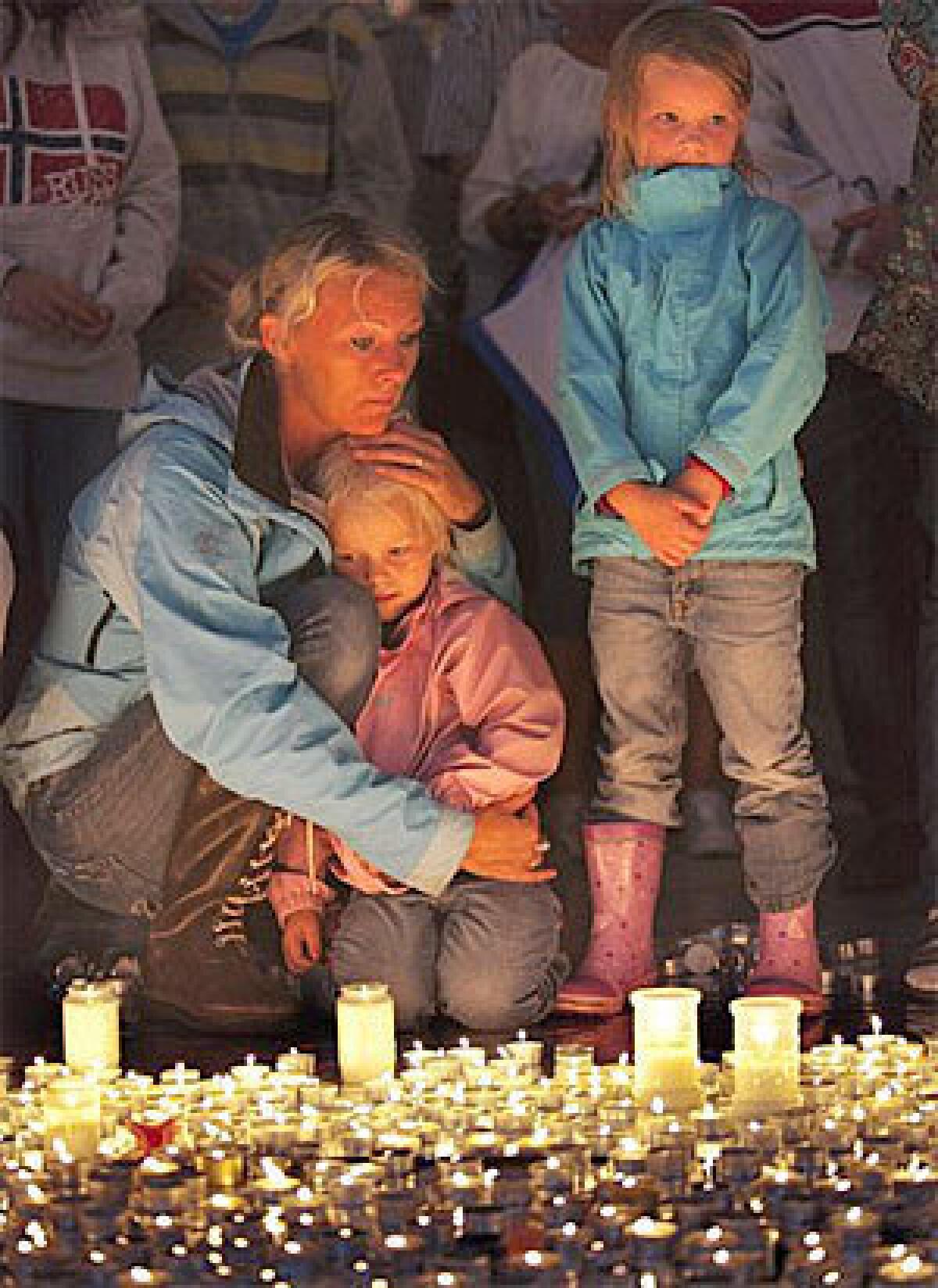

Norway, the scene last year of the deadliest modern massacre by a single gunman, has some of the toughest restrictions on gun ownership in the developed world. Yet Anders Behring Breivik managed to obtain an assault rifle, a high-powered handgun and chemicals used to make a diversionary explosion at the start of his killing rampage that left 77 dead. In his rambling manifesto posted online on the day of his attacks, he boasted that “Ebay is your friend.”

In Germany, another country with strict gun control laws, legislators reacted to a 2002 shooting at a high school in Erfurt with stiffer penalties for negligent storage of firearms after the 19-year-old gunman used a legally registered Glock to kill 16 before taking his own life. Seven years later, when another troubled teen targeted a school in Winnenden, his father was prosecuted for involuntary manslaughter and convicted last year for failing to secure the legally registered 9-millimeter Beretta his son used to kill 16, including himself.

Finland, which trails only the United States, Yemen and Switzerland in per-capita gun ownership, according to the Geneva-based Small Arms Survey, debated tightening gun laws after two school shootings in 2008. Lawmakers concluded two years ago that further legal action was unnecessary.

Still, the consensus among public safety experts is that fewer guns in private hands equates to fewer firearms deaths and gunpoint crimes.

University of Brighton criminology professor Peter Squires attributes the rise in shooting deaths in Britain in the late 1990s to corresponding growth in gang and organized crime activity, a phenomenon that peaked in the early part of the last decade and has since declined year to year.

“There is no act of Parliament, no act of Congress, that can guarantee there’ll never be a massacre,’’ former British Home Secretary Jack Straw, who introduced the ban on gun ownership after the Dunblane killings, commented to British journalists after the eerily similar Newtown, Conn., rampage.

‘‘However,” Straw concluded, “the more you tighten the law, the more you reduce the risk.”

Former Australian Prime Minister John Howard, a conservative who led the bipartisan reforms on banning weapons and the buyback of more than 650,000 guns after the Port Arthur massacre, was visiting the United States this summer when a gunman shot and killed 12 at a movie theater in Aurora, Colo.

Howard argued in a commentary for the Age newspaper in Melbourne that Australia was correct to ban weapons and that the United States would be wise to do the same.

Homicides involving firearms dropped by 59% in the decade following Australia’s gun law reforms, Harvard University researchers reported last year in an analysis of the Australian statistics.

“In the 18 years prior to the 1996 Australian laws, there were 13 gun massacres (four or more fatalities) in Australia, resulting in 102 deaths,” Howard noted. “There have been none in that category since the Port Arthur laws.”

RELATED:

NRA responds to Newtown massacre

White House considers responses to Connecticut shooting

Utah sixth-grader brings gun to school, fearing another Newtown

A foreign correspondent for 25 years, Carol J. Williams traveled to and reported from more than 80 countries in Europe, Asia, the Middle East and Latin America.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.