We need a better way to pick FISA court judges

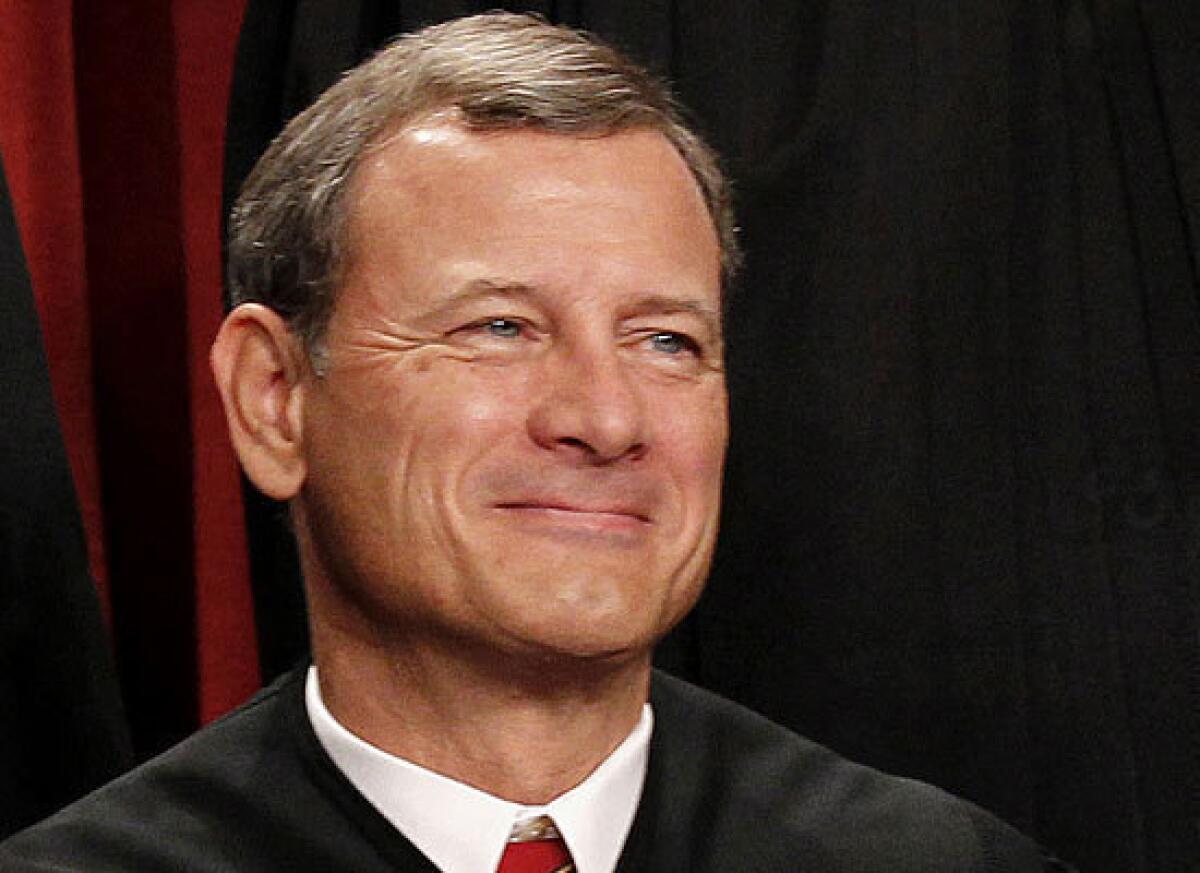

When John G. Roberts Jr. appeared before the Senate Judiciary Committee that was weighing his nomination as chief justice, he was asked about the then-obscure Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, whose members are federal district judges appointed by the chief justice.

The FISA court, as it’s known -- after the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act that created it -- meets in secret to consider requests from the government for electronic surveillance of both suspected foreign agents and terrorists in the United States and foreign “targets” abroad. Among the documents released by NSA leaker Edward Snowden was an order from the court authorizing the collection of telephone metadata of American citizens.

“When I first learned about the FISA court, I was surprised,” Roberts told the committee. “It’s not what we usually think of when we think of a court. We think of a place where we can go, we can watch, the lawyers argue, and it’s subject to the glare of publicity. And the judges explain their decision to the public and they can examine them.”

But now, some civil libertarians fear, Roberts has accustomed himself to the closed nature of the court and is using his appointment authority to “pack” it with judges who will rubber-stamp invasions of privacy.

Without exactly making that argument, Washington Post columnist Ezra Klein noted that “Roberts’ nominations to the FISA court are almost exclusively Republican. One of his first appointees, for instance, was federal District Judge Roger Vinson of Florida, who not only struck down the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate but the rest of the law too.” (I’m not sure what the relevance of the judge’s view of Obamacare is.)

I’m not convinced that Roberts is packing the court with patsies for the national surveillance state. But it is anomalous that all 11 members of this important court are appointed by the chief justice, albeit from a pool of judges nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate for ordinary federal trial courts.

It would be better if its members were chosen specifically for this assignment by the president and confirmed by the Senate. That’s the case with another specialized court, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which hears cases involving patents, intellectual property and international trade.

Presidential nomination and Senate confirmation of judges for the FISA court would allow senators to question nominees about their view of the 4th Amendment and constitutional privacy rights. It would be preferable to a jury-rigged proposal contained in legislation offered by Rep. Steve Cohen (D-Tenn.). His FISA Court Accountability Act would divide appointments to the court among the chief justice, the speaker of the House, the Senate majority leader and minority leaders of the House and Senate. Having members of Congress choose judges -- even from a pool of judges originally named by the president to a different court -- is troublesome from a separation-of-powers perspective.

Whatever the effects of Snowden’s revelations, it’s likely that the FISA court will continue to play an important (and, we can hope, more transparent) role in balancing national security and privacy rights. Its judges should not be part-timers selected by the chief justice. They should be nominated for this special role by the president and confirmed by the Senate.

ALSO:

Latest jobs report makes the case for tax reform

Is Ruth Bader Ginsburg too old to be a Supreme Court justice?

Hawthorne dog shooting: Have some sympathy for the police officer too

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.