Egypt’s students of democracy

As the Egyptian military bowed to millions of demonstrators in the streets to end the presidency of Mohamed Morsi, familiar naysayers reemerged to claim that the protests and the coup show the futility of seeking democratic reform in Egypt and, by extension, the rest of the Arab world. They could not be more wrong. Quite the contrary, the Egyptian people have proved extraordinarily adept students of democracy.

It’s true that deposing an elected president after just one year in office is hardly ideal. And the military’s open reengagement in Egyptian political life is unnerving for those who saw the abuses of power under successive military governments before Morsi’s election. But given the alternatives, the Egyptian people acted wisely.

Events in Egypt are starkly different from those in Algeria a generation ago, when the military’s cancellation of an election that Islamists were poised to win sparked a long, bloody civil war. No popular outcry led to that military intervention; very much the opposite: Algeria’s Islamists went to war because they could only conclude that they had no peaceful, democratic path to governance.

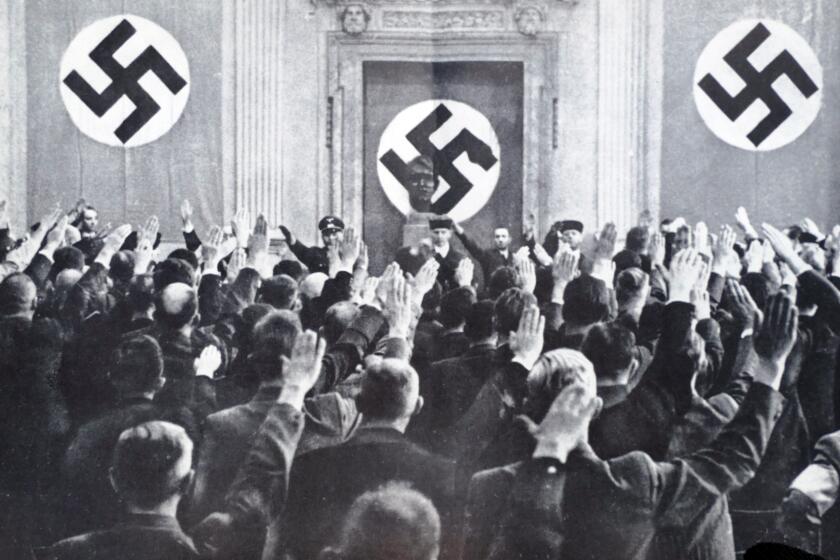

PHOTOS: Massive protest against President Morsi in Egypt

Morsi’s problems, by contrast, were with the Egyptian people. The military, eager to repair a reputation badly damaged during the long dictatorship, has belatedly sought to align itself with the people — just as the Muslim Brotherhood did in 2011 once it became apparent that the revolution was going to succeed.

Islamists represent perhaps a quarter of Egyptian voters, according to noted Egyptian sociologist Saad Eddin Ibrahim. A skewed election law and the secular democrats’ disorganization (with many of their leaders in prison) allowed the Brotherhood to take almost half the seats in a parliamentary election 18 months ago, an election the courts later held was unlawful.

Morsi’s presidential win pitted him against other Islamists, figures from the old government and a leftist Nasserite. The old government’s election commission refused to allow secular liberal candidates to run. Indeed, the run-up to the election was marked by intense repression of secular democrats by the military government that replaced Hosni Mubarak: arrests and torture of nonviolent activists, military courts giving bloggers long prison sentences for insulting the government, and armored military vehicles driving into groups of peaceful demonstrators.

So although Morsi did receive a (narrow) mandate over the old government, he had none over secular democrats and thus had no basis for demanding that they honor the results of an election from which they were largely barred.

Time and again, Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood had opportunities to establish the democratic legitimacy that their tainted election victory lacked. But instead, they put the narrow interests of their political machine over those of the nation.

The Brotherhood’s defenders argued for “honoring the constitution.” But rather than seeking broad participation and consensus from all segments of society in writing that constitution, the Brotherhood was able to pack the drafting commission with its members and ram the result through over the vehement objections of secular democrats, Coptic Christians and others.

It’s true, as the Brotherhood has argued, that the judiciary remains dominated by the old dictatorship’s appointees. But when given the chance to appoint judges and prosecutors, Morsi favored Brotherhood partisans over respected neutrals.

It’s also true that much of the hardship that ordinary Egyptians are experiencing can’t be blamed primarily on Morsi; it’s the result of decades of economic mismanagement and corruption under the Mubarak dictatorship. But in other countries, similar national emergencies have led to national unity governments. The Brotherhood, however, rebuffed numerous appeals from secular democrats for such a coalition.

Morsi and the Brotherhood have expressed legitimate worry about the corrosive effects on a democracy of political violence. Those concerns should have been heeded when Brotherhood thugs beat and killed nonviolent anti-Morsi protesters during the last year. (Fortunately, this week’s demonstrations have been mostly peaceful.)

The Muslim Brotherhood could have shown a commitment to democracy by appointing an impartial election commission, passing an election law to ensure transparency and allowing Egyptian voters to replace the parliament that Egypt’s Supreme Court held was unlawfully chosen. Morsi could have reformed the dreaded security police and released political prisoners. Instead, he retained the illegitimate (Islamist-dominated) parliament and presided over continued repression, including a high-profile trial in which several dozen members of nongovernmental organizations were convicted of doing voter education work without a license, much of it supported with U.S. aid.

The Egyptian people clearly gave Morsi a chance. In the months following his inauguration, turnout for demonstrations against ongoing repression declined significantly as people returned to their daily lives. Continued economic mismanagement, and the Muslim Brotherhood’s clear preference for machine politics over democracy-building, brought Egyptians back to the streets in force.

[Updated: 1:45 p.m. July 5: The military’s action looks remarkably unlike a standard coup. The defense minister, chosen by Morsi, met extensively with a broad cross-section of society before acting. He was joined, and immediately supported, in his announcement by leaders of secular and other Islamist parties and by the senior Muslim and Coptic clerics in Egypt.

The military announced an independent, broad-based committee of experts to a new constitution based on the essentially secular constitution of 1971 (which predates the Mubarak dictatorship). It set out a brisk timetable for new elections.

And, perhaps most important, it did not seize power for itself but rather made the head of the Supreme Court interim president. Chief Justice Adly Mansour, recently elevated to that position by Morsi, was a holdover from before Mubarak began to stack the high courts with his cronies. By drawing an interim leader from the most independent and respected governmental institution in the country rather than its own ranks, the military suggests that rebuilding Egypt (and its own reputation) is its priority, not seizing power for itself.

Reports of scattered violence are troubling, but so far the military seems to be taking great pains to emphasize that the Muslim Brotherhood, like all Egyptians, retains the right to peaceful protest.]

No democracy can long endure unless the electorate is proficient at ridding itself of self-serving politicians who betray the public trust. By turning on Morsi, and by extension, the Brotherhood, Egyptians are showing that they have learned that crucial lesson. The Brotherhood now will have to spend time in the political wilderness, learning the lessons of its fall much as overreaching parties the world over do. And if the military exceeds its popular mandate and seeks to reclaim power for itself, the Egyptian people will have an answer.

David A. Super, a law professor at Georgetown University, is active in Voices for a Democratic Egypt.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.