Goldberg: Egypt’s ‘moderate’ despot

What do you call a leader of a theocratic and cultish movement with a deep and clear disdain for democracy who suddenly assumes dictatorial powers? A “moderate,” of course.

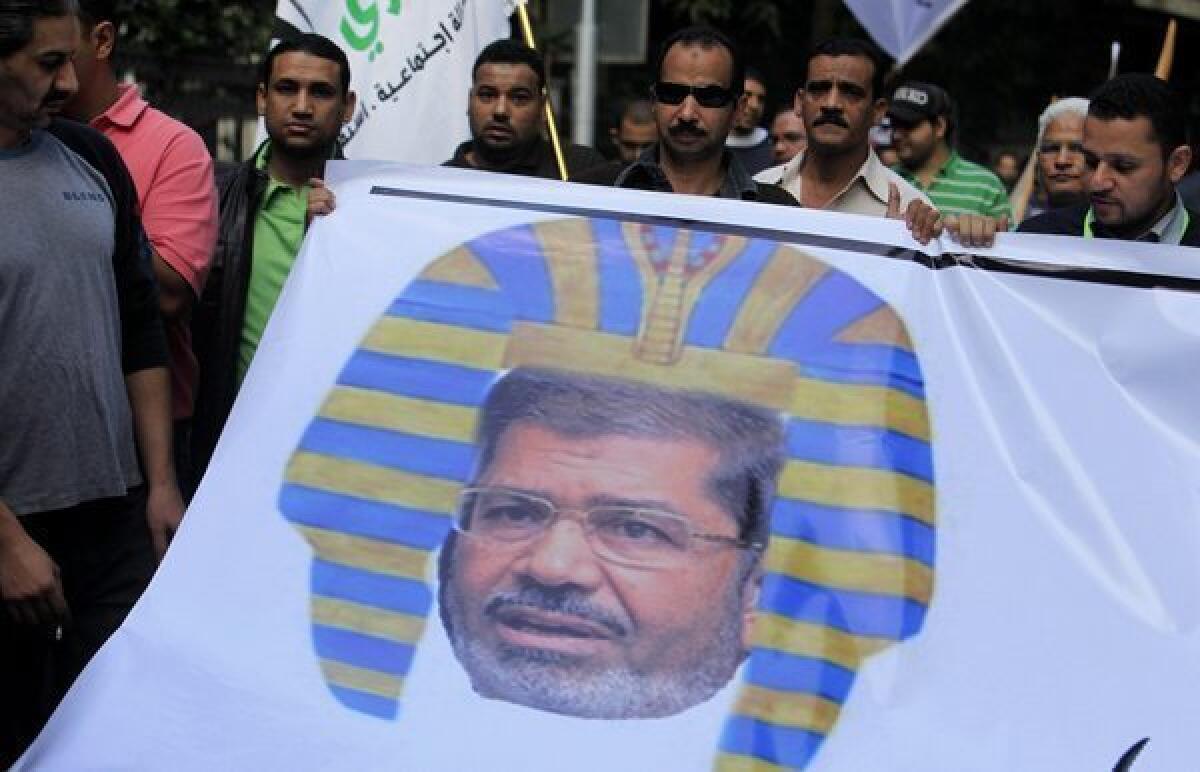

Ever since the Muslim Brotherhood broke its promise to stay out of Egypt’s presidential election in the aftermath of the revolution, many Western observers have been in denial about what has been going on. In less than half a year, Mohamed Morsi has deftly built the apparatus of despotism.

Much as the Nazis brilliantly cast themselves as reformers sweeping away the corruption of the Weimar Republic, Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood have been using the effort to clean up the detritus of Hosni Mubarak’s dictatorship as an excuse to consolidate power.

In August, when Islamists attacked Egyptian soldiers in the Sinai (in an apparent effort to force Egypt into a confrontation with Israel), Morsi used the incident as an excuse to replace Mohamed Hussein Tantawi — a Mubarak-era holdover who headed the military and guarded its independence — with officers more pliable to the Brotherhood.

“Are we looking at a president determined to dismantle the machine of tyranny,” Alaa Al Aswany, a popular novelist and democratic activist, asked at the time, “or one who is retooling the machine of tyranny to serve his interests?” That question quickly became, at best, rhetorical.

Morsi proceeded to purge scores of newspaper editors and publishers, declare himself in charge of the drafting of the new constitution and all but wore a sandwich board with the words “I’m becoming a dictator!” on it.

As if to hammer it home, last week Morsi announced that his rule was immune to judicial oversight of any kind. He used the failure of the courts to adequately punish Mubarak-era holdovers as an excuse. It was just that — an excuse, not an explanation.

Morsi softened his language Monday, but aides insisted his edict stood. And the Brotherhood’s position remains clear. “If democracy means that people decide who leads them, then [we] accept it; if it means that people can change the laws of Allah and follow what they wish to follow, then it is not acceptable,” the Brotherhood explained on its website in 2005.

Before Morsi was announced the winner of June’s election, the Brotherhood massed in Tahrir Square to make its expectations clear. As one Brotherhood member explained to Eric Trager of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, “We win or we die.” Not a particularly democratic motto.

Morsi did have another excuse for seizing power last week: The timing was good. Because he helped broker a cease-fire between Hamas and Israel, the White House lavished praise on him. Morsi immediately cashed in that political capital.

On the New Republic’s website, Trager posted a devastating condemnation of Morsi’s apologists under the headline “Shame on Anyone Who Ever Thought Mohammad Morsi Was a Moderate.” Trager’s one error is he assumes that, after Morsi’s latest power grab, no one could possibly still think Morsi’s a moderate after Thursday’s decree.

But that’s exactly what many still believe. For instance, on ABC’s “This Week” on Sunday, Time magazine’s Joe Klein spoke for many inside the Beltway when he celebrated Morsi’s role in the cease-fire as a “wonderful sign for the future” because it showed he and the Muslim Brotherhood are “moderates.”

Bear in mind that even as Morsi was pocketing praise from the West, Mohammed Badie, the leader of the Muslim Brotherhood, made it clear that war to liberate Palestine remained its goal, once Muslim unity is achieved. “Jihad is obligatory.”

Apparently, “moderation” in the Middle East has been defined down to not wanting to wage war on Israel right now.

On Monday, a Brotherhood-affiliated TV network announced that Morsi allegedly agreed to limit his power grab, while maintaining that the constitution being drafted by Morsi’s pet Islamists will remain immune to judicial review. That the Egyptian people aren’t lying down for the Muslim Brotherhood’s steamroller is heartening, but that doesn’t mean Morsi’s intended goal is any less obvious.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.