Jack LaLanne dies at 96; spiritual father of U.S. fitness movement

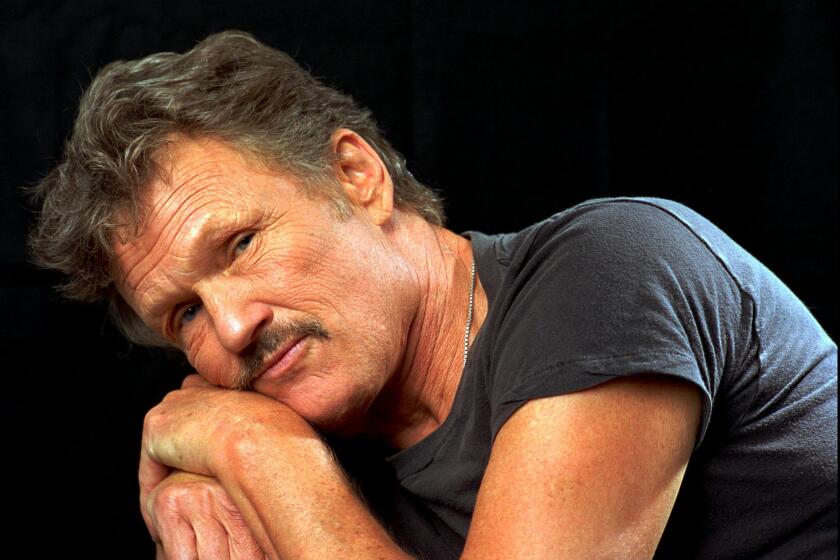

Jack LaLanne, the seemingly eternal master of health and fitness who first popularized the idea that Americans should work out and eat right to retain youthfulness and vigor, died Sunday. He was 96.

LaLanne died of respiratory failure due to pneumonia at his home in Morro Bay, Calif., his agent Rick Hersh said. He had undergone heart valve surgery in December 2009.

FOR THE RECORD:

Jack LaLanne: The obituary of fitness pioneer Jack LaLanne in the Jan. 24 LATExtra section, and a headline accompanying the article online, reported that LaLanne opened what is commonly believed to be the nation’s first health club, in Oakland in 1936. Bodybuilder Vic Tanny, who died in 1985, has been credited with opening an earlier professional gym, in the early 1930s in Rochester, N.Y. —

Though LaLanne was for many years dismissed as merely a “muscle man” — a notion fueled to some extent by his amazing feats of strength — he was the spiritual father of the health movement that blossomed into a national craze of weight rooms, exercise classes and fancy sports clubs.

LaLanne opened what is commonly believed to be the nation’s first health club, in Oakland in 1936. In the 1950s, he launched an early-morning televised exercise program keyed to housewives. He designed many now-familiar exercise machines, including leg extension machines and cable-pulley weights. And he proposed the then-radical idea that women, the elderly and even the disabled should work out to retain strength.

Full of exuberance and good cheer, LaLanne saw himself as a combination cheerleader, rescuer and savior. And if his enthusiasm had a religious fervor to it, well, so be it.

“Well it is. It is a religion with me,” he told What Is Enlightenment, a magazine dedicated to awareness, in 1999. “It’s a way of life. A religion is a way of life, isn’t it?”

“Billy Graham was for the hereafter. I’m for the here and now,” he told The Times when he was almost 92, employing his usual rapid-fire patter.

Another time, he explained, “The crusade is never off my mind — the exercise I do, the food I eat, the thought I think — all this and how I can help make my profession better-respected. To me, this one thing — physical culture and nutrition — is the salvation of America.”

When he started, he knew that most people viewed him as a charlatan. That’s when he decided to do the stunts that made him famous.

“I had to get people believing in me,” he said.

He performed his first feat in 1954, when he was 40 and wanted to prove he wasn’t “over the hill.” He swam the length of the Golden Gate Bridge — underwater. (He carried two air tanks.)

Other feats in his 40s: swimming from Alcatraz to San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf wearing handcuffs; swimming the Golden Gate Channel while towing a 2,500-pound cabin cruiser; pulling a paddleboard 30 miles from the Farallon Islands to the San Francisco shore.

At age 60, he upped the ante by swimming from Alcatraz to Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco, handcuffed and shackled and towing a 1,000-pound boat.

The next year, he did a similar feat underwater. And at age 70, he towed 70 boats with 70 people from the Queen’s Way Bridge in Long Beach Harbor to the Queen Mary — while handcuffed and shackled.

Why attempt such feats?

“I care more than — you cannot believe how much I care! I want to help somebody!” LaLanne explained. “Jesus, when he was on Earth, he was out there helping people, right? Why did he perform those miracles? To call attention to his profession. Why do you think I do these incredible feats ? To call attention to my profession!”

(Italics were essential in re-creating LaLanne’s speech — most writers quoting him also used numerous exclamation points.)

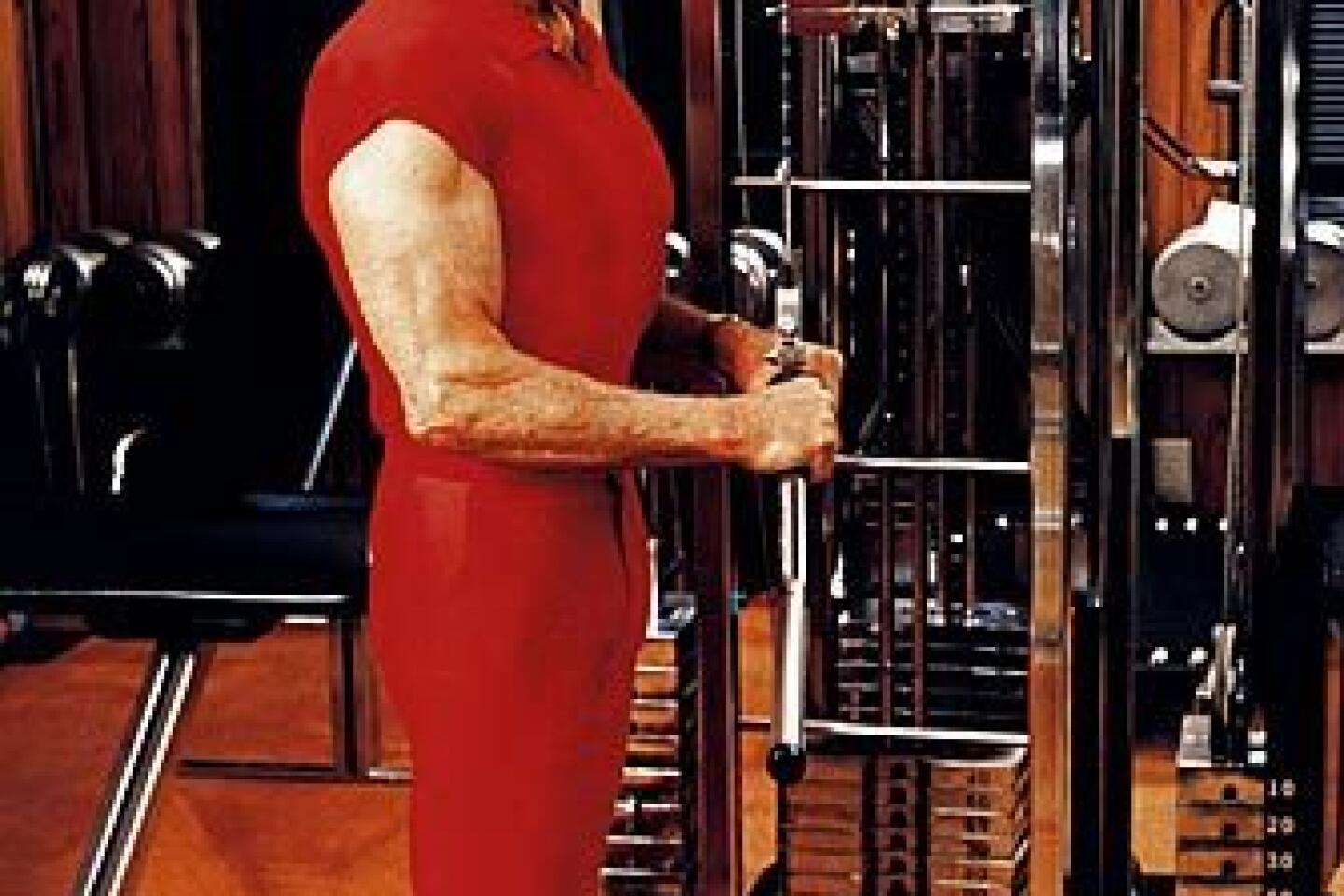

Well into his late 80s, LaLanne continued his personal fitness routine of two hours a day — one hour of weight training and another hour exercising in the pool — beginning at 5 or 5:30 in the morning (a concession to his age; in earlier days, he started at 4 a.m.).

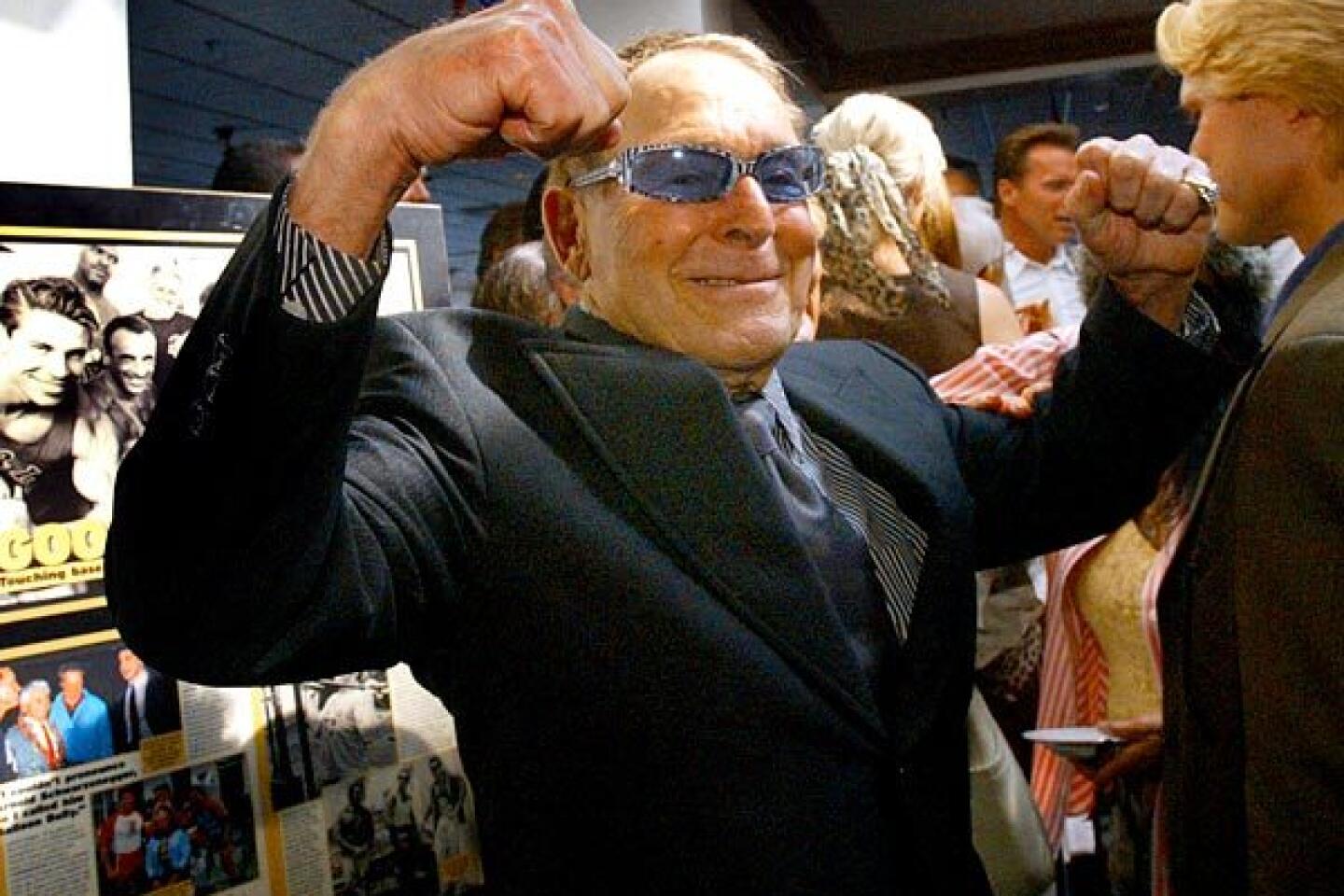

No one — not even Arnold Schwarzenegger — could argue that LaLanne wasn’t the best. Schwarzenegger, who met LaLanne in the 1960s on Muscle Beach on the Venice Boardwalk, said LaLanne would try to see who could match him in numbers of chin-ups and push-ups.

“Nobody could,” Schwarzenegger told The Times. “No one even wanted to try.”

Francois Henri LaLanne (nicknamed Jack by his brother) was born Sept. 26, 1914, in San Francisco to French immigrant parents; his father worked at the telephone company and was a dance instructor and his mother, who was a maid, was a Seventh-Day Adventist, a religion that advocates “eight keys” to good health, including nutrition and exercise.

LaLanne grew up in Bakersfield, where his parents had moved to become sheep farmers, but the sheep contracted hoof-and-mouth disease, and the family moved to Oakland. LaLanne’s father died of a heart attack at age 50.

LaLanne often told the story of how his mother spoiled him, giving him sweets as a reward. By the time he reached adolescence he had become a “sugarholic” with a violent temper and suicidal thoughts.

But that was only the beginning: He was failing in school, his stomach was upset, he wore glasses, he had terrible headaches, he was weak and skinny, he had pimples and boils.

“I was demented! I was psychotic! It was like a horror movie!” LaLanne said of this time of his life.

When he was 15, his distressed mother dragged him to a lecture on healthful living being given by nutritionist Paul Bragg.

“We were a little late getting there and there were no seats available so we started to leave,” LaLanne told What Is Enlightenment magazine’s Andrew Cohen, “and the lecturer saw us and said, ‘Lady with the boy, we don’t turn anybody away! Ushers, bring two seats and put them up on the stage!’ ”

At some point, Bragg asked the young LaLanne what he had eaten for breakfast, lunch and dinner, and LaLanne told him: “Cakes, pies, ice cream!”

“He said, ‘Jack, you are a walking garbage can,’ ” LaLanne said.

But Bragg offered salvation to LaLanne: He could be “born again” and be the healthful and strong person he wanted to be — if he changed his ways.

“That’s what I wanted! I wanted to be an athlete, I wanted the girls to like me, and I wanted to be able to get good grades in school, and this man said I could do all that,” LaLanne said.

LaLanne took Bragg’s message fully to heart. And, by his own testimony and that of everyone around him, he never had cake, pie, ice cream or any sweet from that day forward, nor did he drink a single cup of coffee or tea.

He also started working out with a passion and was a star athlete for the rest of his high school years. All his maladies disappeared; he even stopped wearing glasses.

“I was a whole new human being,” he said of this transformation. “I liked people, they liked me. It was like an exorcism, kicking the devil outta me!”

After graduation from high school, LaLanne started his own business selling his mother’s healthful bread and cookies. He also set up a rudimentary gym and started training police officers and firefighters — “the fat and skinny ones who couldn’t pass their physicals” — in exercise and weightlifting.

“When I first started out, I was considered a crackpot,” he said. “The doctors used to say, ‘Don’t go to that Jack LaLanne, you’ll get hemorrhoids, you won’t get an erection, you women will look like men, you athletes will get muscle-bound’ — this is what I had to go through.”

In 1936, he opened his first real gym — LaLanne’s Physical Culture Studio in downtown Oakland.

But business was slow. LaLanne went to a local high school and picked out the skinniest and the fattest students, offering (with their parents’ permission) to “turn their lives around” the way his had been.

Word of his success spread, and business was good enough for him to open other gyms. In 1952, he went on TV, but because he could only afford time in the early mornings, he found his audience was mostly young children. So he got a dog — Happy — to appeal to the kids, who were encouraged to go wake up their mommies for a workout. The show was eventually syndicated nationwide and ran for 34 years.

LaLanne met his wife, Elaine, whom he called LaLa, in 1950 on the set of a local TV show, where she booked talent. She was initially unimpressed by the 5-foot-6 1/2-inch LaLanne — she ate a doughnut and blew cigarette smoke in his face. But she took a closer look at him when a friend agreed to go out on a date with him. They were married in 1959, and she became an integral part of his business.

LaLanne’s business interests would grow to include a string of gyms across the United States, workout devices like the “Glamour Stretcher” and “JLL Stepper,” vitamins, supplements and several books.

By the time LaLanne was in his late 80s, however, the business consisted mostly of juicers that he advertised on infomercials and his lectures.

LaLanne also knew when to back off. An interviewer described him as “intensely unfussy for being such a fanatic.” And LaLanne once said that one of his best friends was a man who “weighs about 300 pounds, drinks a quart of booze a day and smokes like a fiend. I’ll light someone’s cigarette for them. This bull about changing people — you never change people! Accept ‘em, accept ‘em, accept ‘em!”

For himself, he seemed to live by a there-but-for-the-grace-of-God-go-I philosophy that required him to be hyper-vigilant.

“With my personality,” he said, “I could be a runaway, out with a different woman every night, drunk every night, eating and doing things that — well, you know, you’ve got it in you, we’ve all got it in us. But that’s why you’ve got to take control!”

He had his pleasures — beautiful cars, singing, fine wine and a long and happy marriage that he said was passionate after many decades.

He felt proud every time he fulfilled his promise to himself to never eat between meals or eat sweets. While he was the first to agree that his liquid meals — the least repulsive breakfast was carrot juice, celery juice, some fruit, egg whites and soybean — tasted pretty awful, he didn’t mind. And of his two-hour daily workouts at his home gym, which he called his “cathedral,” he said: “I want to see how long I can keep this up. It’s kind of a macho thing, using me as an example.”

LaLanne retained a high level of energy well into what, for the rest of us, would be dotage. But his feats tapered off after his 70th birthday. Although he talked of swimming underwater to Catalina Island for his 80th birthday, his wife threatened to divorce him if he did. “Let him rest on his laurels,” she said. He vowed to do the swim for his 90th birthday in 2004, but when the birthday rolled around, he told the San Jose Mercury News that he planned only to “tow my wife across the bathtub.” His plans for his 100th were even tamer: “I’d like to have the biggest group I’ve ever had watching me and lecture to them.”

LaLanne was given a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame in 2002, long after he had attained the respect he long craved. But his biggest thrill was to see that what he had been preaching and advocating for more than 50 years was being taken seriously.

“Back then I was a crackpot; today, I am an authority,” he said in 1998.

Besides his wife, LaLanne is survived by Elaine’s son, Dan Doyle, of Los Angeles; LaLanne’s daughter by his first marriage, Yvonne, a chiropractor, of Walnut Creek; and the couple’s son, Jon, of Kauai, Hawaii.

Luther is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.