Syria mother nurtures a hope that her detainee son is alive

Opposition member Abdullah Suood had said he would rather die than return to Syrian government detention and torture. He hasn’t been heard from in more than a year.

On the windowsill next to a photo of her four sons, Ahlam Suood kept her cellphone in the same spot, where the reception was best.

Throughout the day she would run to the phone, thinking she had heard it ring, worried she had missed a call.

"You can't even leave the phone, you keep checking it, maybe someone called," Suood said. "Any unknown number that rings, I call it back — maybe it's Abdullah."

She last saw her son Abdullah more than a year ago, when the 24-year-old university student was taken away by security forces.

The family was forced to flee their city of Maarat Numan in northern Syria's Idlib province late last year, and Suood stayed awake at night worrying that Abdullah would be released and then be unable to find her if he returned to the family home.

She refuses to even think about joining the growing exodus of Syrians who are leaving the war-torn country. Here, even in a town not her own, she feels closer to her son.

"I won't leave before Abdullah gets out," she said. "I'm not worth more than my children; I'm not worth more than Abdullah."

The Syrian civil war, now in its third year, has left more than 100,000 people dead, according to the most recent United Nations figures. About twice that number have disappeared inside government prisons or other security detention facilities where they languish in inhumane conditions, according to the opposition Syrian Network for Human Rights.

About 70,000 have not been heard from since they were taken, said the group's spokesman, Sami Ibrahim.

For families, the lack of information can foster hope that the detainee will eventually be released. On the other hand, the relatives may wait forever for closure.

Mothers like Suood live from one bit of news to the next.

Almost a year ago, a man was freed from prison and sent word to the family that Abdullah was alive and was expected to be released soon. Then, nothing. No release and no further news.

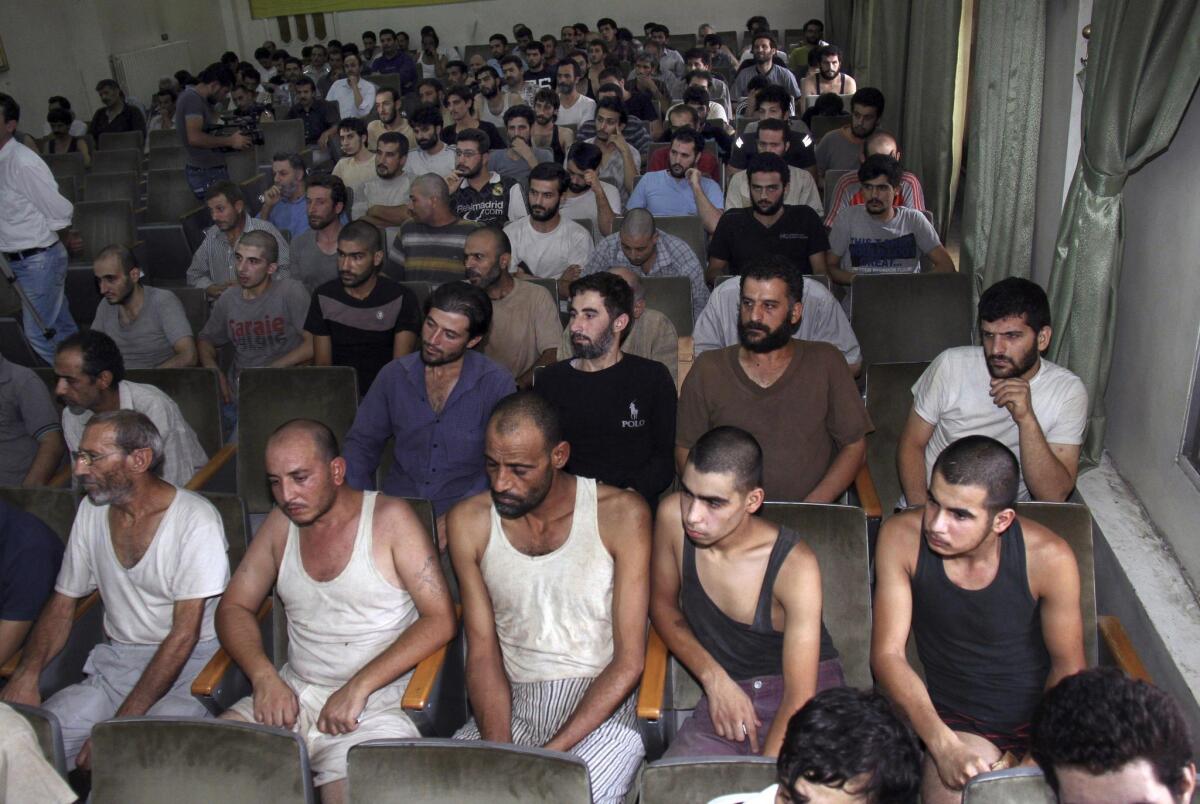

Syrians detained for taking part in antigovernment protests sit in a Damascus courtroom before their release last summer. (Bassem Tellawi, Associated Press)

Whenever Suood heard of a newly freed detainee in Idlib province, she would make the trip to congratulate the man and his family and inquire about her son. It is a largely futile practice repeated by other families desperate for any word of a loved one.

In late May, a rebel fighter contacted the Suood family and told them he had been with Abdullah in a Damascus intelligence compound known as the Palestine branch.

The fighter, released as part of a prisoner swap for government soldiers, said Abdullah was in relatively good health despite the difficult conditions. But even that bit of good news was laced with the ominous.

In the Palestine compound, the freed fighter said, prisoner executions had become regular occurrences. At times, he told them, the hallways flowed with blood.

But Suood's hope persists.

"You dream every day that tomorrow he's going to be released," she said, wringing her hands. "When my [other] sons come, I dream that it's going to be him ringing the doorbell."

When you first fall into the hands of the security forces, you don't know what your fate is or where your destiny lies. You know you can die in any way."— Abdulrahman Suood

Abdulrahman Suood can't remember his experience in government detention without thinking about his older brother Abdullah.

"When you first fall into the hands of the security forces, you don't know what your fate is or where your destiny lies," the 22-year-old said. "You know you can die in any way."

The brothers were crammed into 13-square-foot cells that held dozens of men. They were regularly beaten, but nothing was worse than the degradation, he said.

Once when Abdulrahman was undergoing a strip search and interrogation, a guard asked him where he was studying.

He said he was a mechanical engineering sophomore at Aleppo University, a public university.

"You're studying with us and you're coming out in protest against us," the guard said, and then spit on him.

Their days were filled with interrogations and waiting in rooms so crowded with detainees that they had to take turns sleeping.

"The wait is very hard. Every night I would pray that the next morning I would hear my name and I would be released," he said.

In April, Human Rights Watch visited state security and military intelligence facilities in Raqqah province, now under opposition control, where they found documents, prison cells, interrogation rooms and devices consistent with the torture former detainees have described.

A photo released by Human Rights Watch shows a torture device on the floor of a government security building in Raqqah, Syria. Rights activists visiting abandoned government prisons there say they have found evidence of detainee abuse. (Bryan Denton, Associated Press)

Since the beginning of the uprising in March 2011, the rights group has documented the systematic patterns of abuse and torture, which it says amount to crimes against humanity. The group has urged the U.N. Security Council to refer the situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court.

The last time Abdulrahman saw his brother was on April 20, 2012, when they were taken out of their cells in Damascus to be interrogated.

When he was released after three months, Abdulrahman at first couldn't believe it. He still doesn't understand why he was let go and Abdullah wasn't.

"I can't forget what happened. I try not to think about it, but there are some things that you keep remembering," he said. "Abdullah doesn't leave my mind at all."

When Abdullah Suood was released after his first detainment, he vowed never to be taken alive again.

"Let them kill me rather than detain me," he would say.

Before the uprising began, Abdullah was one of many online activists trying to organize protests to emulate the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt. He went to Aleppo three times in February 2011 for planned protests that never materialized.

On his fourth trip, just before demonstrations broke out across the country, Abdullah was arrested and held for two months, enduring what he described as regular beatings and electric shocks.

A Syrian man in Aleppo, released after being held by government forces, shows the marks of torture on his back. (James Lawler Duggan, AFP/Getty Images)

It was Abdullah who inspired his family to join the uprising. His father, a doctor, volunteers in the field hospital and two of his brothers work in Maarat Numan's media office. Ahlam Suood knits scarves and sweaters in the colors of the opposition flag.

"He wasn't afraid," Suood said of her son.

But his time in prison changed him.

He began carrying a handgun wherever he went in case he was caught again. He didn't plan to use it against the security forces, but to make them kill him once he brandished the gun.

But a twist of fate robbed him of the gun in February 2012.

Abdullah and Abdulrahman were on their way from their hometown to Aleppo to attend upcoming protests. They were halted on the highway by Bedouin thieves who took the gun, their money and their cellphones.

After the robbery, the brothers continued to Aleppo. At a gas station there, they were stopped by security officers.

In his pocket, Abdullah had a list of activists and the phone number for Col. Riad Assad, then head of the rebel Free Syrian Army. Abdullah was accused of being an opposition coordinator, a media activist and a source for Al Jazeera news channel, viewed as pro-opposition.

From there he disappeared into the labyrinth that frightened him more than death.

Follow Raja Abdulrahim (@RajaAbdulrahim) on Twitter

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.