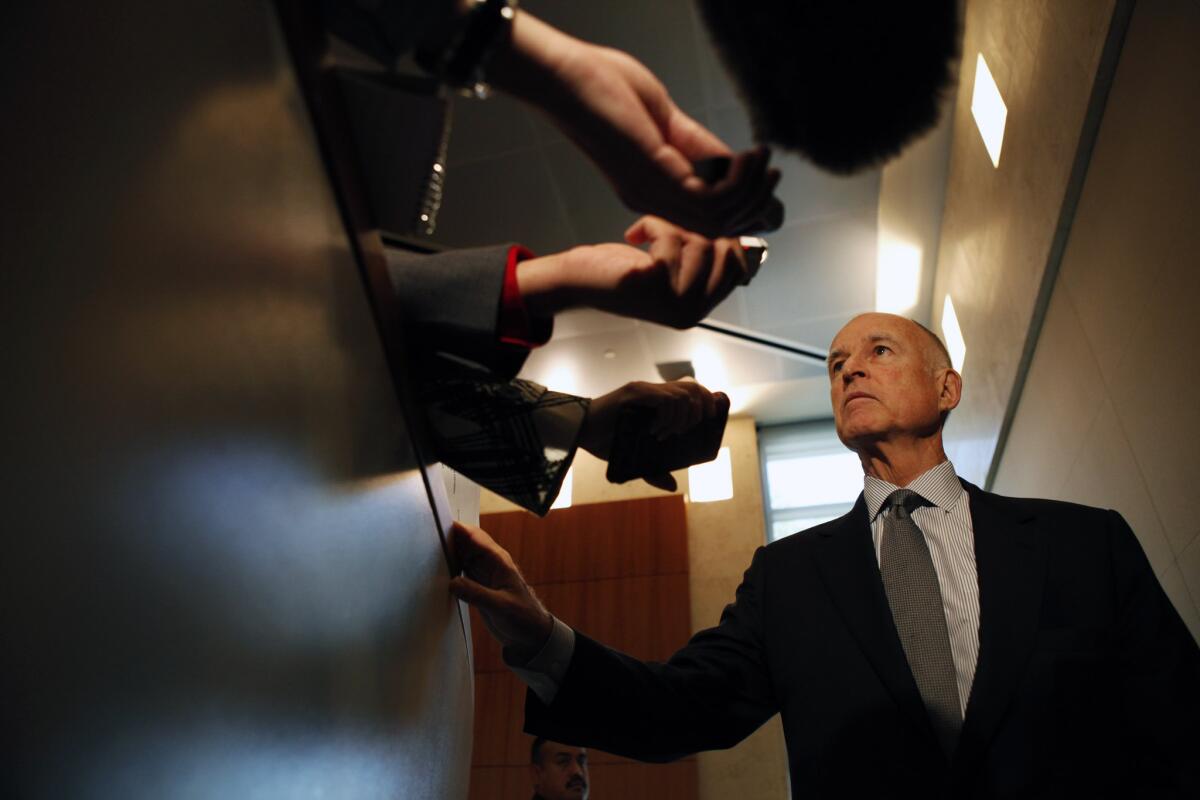

Brown retreats from conditions on university funding

SACRAMENTO — Gov. Jerry Brown has backed off his proposal to tie some money for California’s public universities to such requirements as improving graduation rates, enrolling more low-income students and freezing tuition for four years.

University of California and California State University officials fought Brown’s carrot-and-stick approach to higher education, which the governor had embedded in his budget plan.

Brown wanted to steadily increase funding for universities over the next four years as long as they met specific conditions — ensuring more students finish their degrees on time, enrolling more transfers from community colleges and other measures — and to withhold the money if tuition was raised.

Representatives of the universities said Brown’s proposals were too rigid and unrealistic after years of budget cuts, and key lawmakers agreed. As a result of this week’s budget deal, the universities will be required simply to track the number of low-income students they have, the percentage of students who finish within four or six years, the number graduating with engineering and computer degrees and several other statistics.

The $96.3-billion spending plan scheduled for a vote in the Legislature on Friday contains $250 million more than last year for each university system — and no financial penalties. Both systems said they’re already making progress on Brown’s benchmarks and have agreed to forgo undergraduate tuition hikes for at least the coming academic year.

After that, “we are not etching anything in stone,” said Dianne Klein, a UC spokeswoman. “Plans change from year to year.”

Cal State isn’t planning any tuition increases for the next two years, said spokesman Michael Uhlenkamp.

The stalling of Brown’s quest to overhaul higher education is one of the year’s only setbacks for the governor, who has pushed to reshape the relationship between Sacramento and public universities wary of politicians’ interference. But he still hopes to use the promise of more money to prod the universities to run more efficiently and serve more students.

Evan Westrup, a spokesman for Brown, said that “the governor remains committed to improving the quality, performance and cost-effectiveness of California’s higher-education systems.” He said the requirement for tracking detailed information will “inform the work that’s done moving forward and, ultimately, help improve higher education in California.”

Brown, lawmakers and university officials will revisit his proposals later this year, another spokesman said.

State Sen. Marty Block (D-San Diego), who chairs a budget subcommittee on education, said the Legislature needed more time to consider Brown’s plans, which the governor detailed in April. “This is fairly revolutionary,” he said. “It’s not something we want to force quickly.”

Assemblywoman Susan Bonilla (D-Concord), Block’s counterpart in the Assembly, said resistance to Brown’s plans became evident quickly, and the governor did not appear ready to “draw a line in the sand.”

Brown was already engaged in wide-ranging debates over redistributing school funding to help needier districts, expanding the state’s healthcare program to comport with the federal overhaul and reining in optimistic revenue estimates — all issues in which he largely prevailed.

The budget plan also includes a proposal to help reduce tuition for students from middle-class families, a priority for Assembly Speaker John A. Pérez (D-Los Angeles).

Bonilla said she was concerned that Brown’s higher-education proposal was generated by number crunchers without enough input from educators. During an April hearing, she said the governor made it sound “like we’re talking about a factory” rather than a university.

And universities are in a rebuilding phase, she said: “I don’t think that’s the time to say we’re going to withhold your money.”

Patrick Lenz, UC’s vice president of budget and capital resources, called Brown’s original plan “punitive.”

One element of the budget would change California’s public-records laws, making some requirements for how local governments and agencies handle requests voluntary. Local officials would no longer have to respond to a request for documents in 10 days or provide them in an electronic format.

Administration officials say the change could help the state save tens of millions of dollars in reimbursements to local officials for complying with the laws. But open-government advocates are concerned that the changes would make it tougher for the media and the public to see government records.

Times staff writer Larry Gordon contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.