For Jimmy Carter, a more personal mission

PLAINS, GA. — Jimmy Carter still spends much of his time injecting himself into the nastiest spats on the planet. But most Sundays, the 83-year-old former president manages to be back here in the tiny city where he was raised. He does not like to skip Sunday school.

He gives his Bible lessons at Maranatha Baptist Church, an unassuming red-brick chapel on the outskirts of town. Carter estimates that he has given more than 450 of them since leaving the White House in 1981.

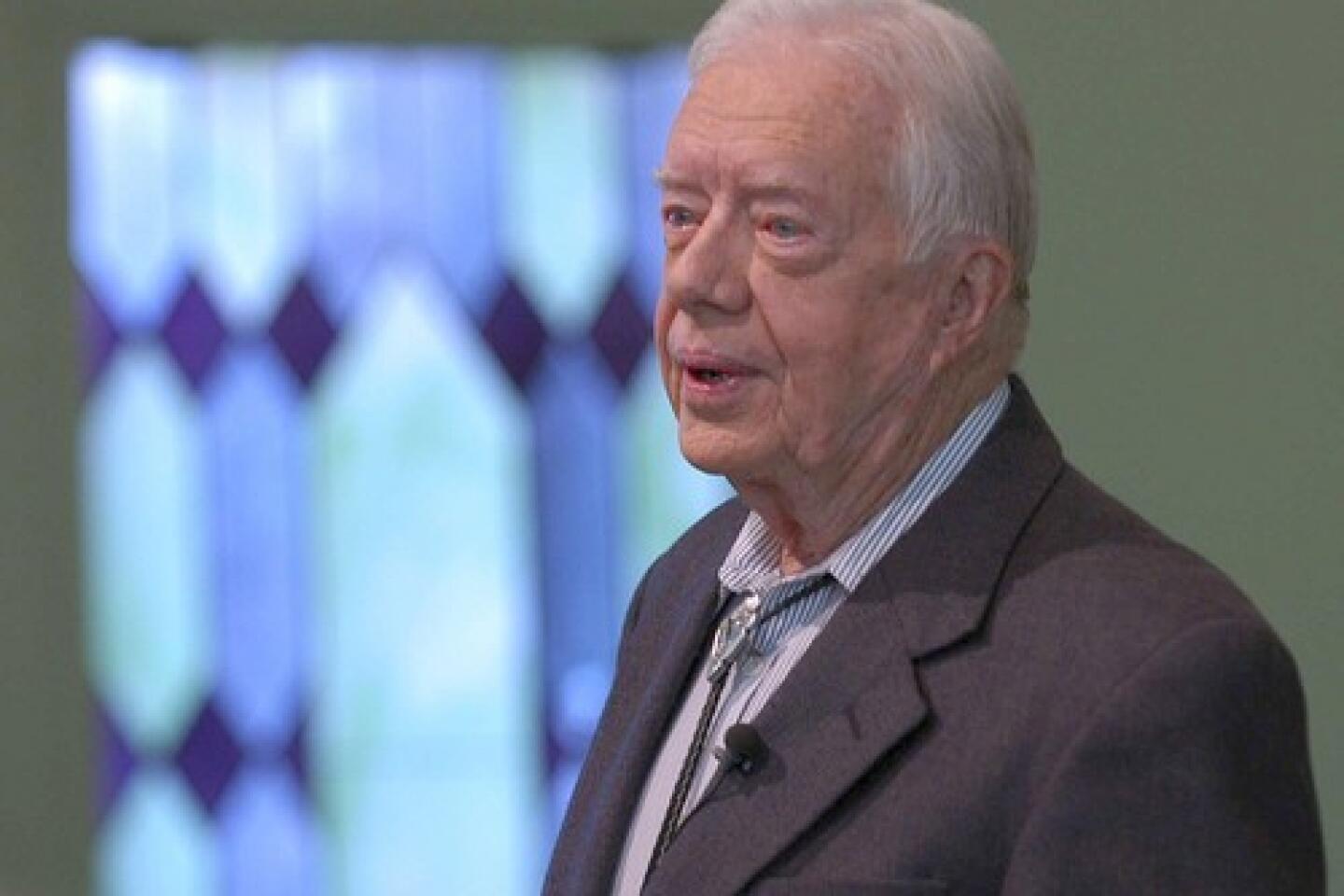

On a recent bitter-cold morning,the chapel crowd was a typical one -- mostly out-of-towners, with a sprinkling of locals and stone-faced Secret Service agents. Carter appeared at 10 a.m. in a gray blazer and bolo tie. His hair was thinning and white, his face withered and creased. But that plush, toothy smile flashed like old times, and his voice was clear and firm.

He spoke about Christ’s insistence that people love their enemies.

“It is one of the most difficult things for human beings to do,” Carter said. “But Jesus said this because he meant it.”

That directive has driven Carter to try his hand at healing the rifts between the great antagonists of the last half-century: Arab and Jew, Cuban and American, Hutu and Tutsi. For his efforts, he has been honored with the Nobel Peace Prize and derided as a quixotic fool.

But there is one divisive row that is perhaps the most personal for Carter, and his failure to heal it has haunted him for years. It is the rift between liberals and conservatives within his own religion -- a battle that has left him estranged from the Southern Baptist Convention, the Protestant entity that once nurtured and defined him.

“It really grieved me to see my own depository of religious faith . . . being ripped apart,” Carter said. “It was very deeply troubling. And I have felt, maybe unjustifiably, a personal obligation to try to do something about it.”

With more than 16 million members in 50 states, the Southern Baptist Convention is the largest Protestant group in the United States. But for many white Southerners of Carter’s generation, it was more than a denomination.

Southern Baptist churches inspired young Christians like Carter to harvest unsaved souls on far-flung missions. The convention’s bureaucracy offered ambitious Baptists like Carter a venue outside of government where they could slake their desire to lead.

It was superstructure for a culture -- a world of covered-dish casseroles and church homecomings and “Are You Washed in the Blood?” sung from old hymnals. It was almost a tribe.

“The curse and the genius of the Southern Baptist Convention for Carter’s generation is that it inculcated a sense of Baptist identity that is so deep in people that it was hard to give up,” said Bill Leonard, dean of the divinity school at Wake Forest University and a liberal Baptist. “It shaped your spirituality -- but also your own sense of who you were.”

Carter remembers that culture as being tolerant of divergent viewpoints. But when he left the White House in 1981, a conservative faction within the convention had begun to take over, and liberals like him felt spurned. Many left the fold: Carter and his wife, Rosalynn, publicly distanced themselves from the convention in 2000.His latest attempt at a rapprochement resulted in an ambitious meeting of Baptists of all stripes this week in Atlanta. The meeting, which concludes today, is called the Celebration of a New Baptist Covenant, and it has united strains of Baptists who went their separate ways years ago. Among them are the Northern Baptists, who split with Southerners over the slavery issue in 1845, and black Baptist groups that have organized separately since the Civil War.

But the Southern Baptist Convention leadership refused to attend. In May, President Frank Page, whom Carter personally invited, denounced the meeting’s “smoke-screen left-wing liberal agenda.”

He argued that Carter and other organizers were calling for unity after spending years disparaging their conservative brothers. Page said Carter once equated the rise of the Baptist conservatives to the rise of Iran’s Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. It was an apparent allusion to a chapter in Carter’s 2005 book, “Our Endangered Values,” which was highly critical of the Christian right.

In this peace effort, Carter is not a disinterested third party.

Thousands flock to Plains each year to hear Carter speak at Maranatha. Pastor Jeff Summers said it was the only church he knew that performed worldwide missionary work “without going anywhere.”

Visitors can have their picture taken with the president and former first lady, but only after sitting through Carter’s 45-minute Bible class and the hourlong church service that follows.

“You get a reward, I guess,” Summers said, smiling.

Plains, with 634 residents, remains a working farm town, but it is also a sort of Jimmy Carter amusement park. Its rail depot and high school are now Carter museums, and the downtown is permanently festooned with Carter campaign signs, in a sort of eternal 1976.

Carter’s home is here too, on a road out of town, set inconspicuously behind a heavy automatic gate and a Secret Service outbuilding. The house is a modest ranch, lived-in and cozy. After Sunday school, Carter sat in the front parlor, where he discussed, with more care than candor, his troubled relationship with his former denomination.

His father, a farmer, was a Sunday-school teacher and deacon at Plains Baptist Church, which was affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention. Though blacks were not allowed to worship in white churches when Carter was a boy, he remembers it as a time of harmony. The church, he said, “comprised Christians of all basic theological or political persuasions. I mean, there wasn’t any distinction.”

After serving as a Navy officer, Carter returned home in 1953, where he ran his family’s peanut business and taught Sunday school. In 1966, after losing the governor’s race, his faith wavered, but it was restored by mission work. He can still recall the number of souls he and a man from Texas saved -- 48, to be exact -- during a weeklong excursion in Lock Haven, Pa. He was eventually elected to the convention’s commission that governed men’s mission activities.

“It was a big deal for somebody from Plains, Ga.,” he said.

It was during Carter’s presidency that the conservative tide began rising in the Southern Baptist Convention, part of a broader national backlash against the ideas and attitudes of the 1960s and ‘70s.

A campaign had emerged to promote the idea that the Bible was entirely without error, even in matters of history and science. Some feared that more liberal theological positions were being taught in the convention’s seminaries.

In June 1980, the conservative faction chose its second president, an Oklahoma evangelist named Bailey Smith. At the same convention, resolutions were passed opposing abortion and the Equal Rights Amendment. Soon after his election, Smith declared, “God almighty does not hear the prayer of a Jew.”

In August, he visited the White House. In “Our Endangered Values,” Carter recalls Smith saying, at the close of their meeting, “We are praying, Mr. President, that you will abandon secular humanism as your religion.”

“This was a shock to me,” Carter later wrote. “I considered myself to be a loyal and traditional Baptist, and had no idea what he meant.”

Carter met with the pastor of his moderate Baptist church in Washington, and they discussed the positions he had taken that had likely offended the ascendant Christian right -- his appointment of women to positions of power, accepting the Roe vs. Wade decision legalizing abortion, supporting public schools, calling for a Palestinian homeland.

After being defeated by Ronald Reagan -- a close ally of the convention’s conservative wing -- Carter retreated to Plains, and the stately, twin-steepled church of his father. Like many Southern Baptist churches at the time, it was struggling with racial integration. A faction with liberal racial attitudes broke off to form the Maranatha church, and Carter and his wife eventually joined them.

During this time, many liberals were defecting from the convention, and some were being drummed out of its institutions. Liberals charged that the church had grown too cozy with the Republican Party, and alleged that conservatives were stymieing academic freedom in the seminaries by insisting that teachers adhere to a strict set of beliefs.

Carter wanted to do something about it.

“I had been loyal to the Southern Baptist Convention all my life, and I was a former president,” he said. “I thought I had some influence -- which I did.”

In 1997 and 1998, Carter called conservative and liberal Baptists to the Carter Center, the nonprofit located next to his presidential library in Atlanta. Participants recall he treated them like any warring parties from abroad.

“Just like the Palestinians and Israelis,” Leonard said.

Tensions were high. Carter met first with a group largely made up of liberals and moderates, then with a conservative faction. It was an echo of his work at Camp David two decades earlier, when he shuttled between the cabins of the mistrustful rulers of Israel and Egypt.

The leaders of the two groups signed an accord promising to work together. But the goodwill did not last. In 2000, Carter was upset by an alteration of the convention’s creed that he saw as substituting Southern Baptist leaders for Jesus as the interpreters of Scripture.

“Since then, the Southern Baptist Convention has become increasingly narrow in its definition of who is welcome,” Carter said. “They now have decided that women can’t teach men, and that women can’t be deacons, and women can’t be pastors, and women can’t be missionaries, and so forth.”

The peacemaker seemed to catch himself. “Which -- I’m not criticizing them. That’s their prerogative.”

It is the kind of statement that doesn’t help matters.

The Southern Baptist Convention indeed thinks women should not be pastors, and it discourages women from serving as deacons. But Roger “Sing” Oldham, a church spokesman, said there were many female missionaries and Sunday-school teachers in convention churches.

It wasn’t just Carter’s rhetoric that soured church leaders on this week’s meeting. They were also worried about the liberal lineup -- including former President Clinton and former Vice President Al Gore, who gave a speech on faith and the environment. Former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee, a former Southern Baptist minister, said he would attend, then backed out, fearing the agenda would be “political rather than spiritual.”

A former president of the convention, Paige Patterson, noted that schisms were not all bad. The Baptist faith was founded in 1609 by dissenters who thought that people must be old enough to make a conscious choice to accept Christ before they were baptized.

An enduring emphasis on reason and free choice has led to numerous splinterings, and a flourishing of separate Baptist groups with differing opinions on theology and politics. Put two Baptists in a room, an old saying goes, and you’ll get three opinions.

Patterson said the current split boiled down to “an epistemological question: How do you know what you know you say is true?”

“We believe that we know what we know because God has flawlessly revealed to us in the Bible what his will and thought and purpose is,” he said. “They do not believe that.”

Carter, who did graduate work in nuclear physics, doesn’t necessarily disagree. “There’s no doubt in my mind that the Bible was written by, almost exclusively, men, who were limited in their knowledge of science.” Today’s biblical literalists, he said, “might believe that the universe was created in 4004 BC. I don’t believe that.”

But why try to bring such divergent brands of Baptists together? Carter said he was partially influenced by the religious divisions he had witnessed in other parts of the world -- divisions that sometimes led to hatred and violence.

More important, he said, bickering over “temporal” issues poses a threat to the health of the modern church, the same way it threatened the early church in the days of Peter and Paul.

Homosexuality, contraceptives, the role of women, the role of church and state -- “all of those things are deeply felt beliefs on the part of human beings,” Carter said. “I have deep feelings on all those subjects of my own.

“But I don’t see why those beliefs should separate you from me, if both of us believe in Christ and believe in furthering God’s kingdom.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.