Richard Glossip’s execution postponed: See how he landed on death row

Richard Glossip didn't personally kill Barry Van Treese in 1997. He wasn't even in the room when his former boss was slain inside an Oklahoma City motel.

On Wednesday, Glossip was set to face death by lethal injection in Oklahoma based almost entirely on the testimony of the man who actually killed Van Treese. But concerns over the drug cocktail that would be used to kill him led Gov. Mary Fallin to decide late Wednesday to postpone his execution once again.

Glossip's scheduled execution, which has been the subject of widespread criticism, had already been delayed twice. The state's Criminal Court of Appeals heard a challenge this month but decided Monday not to grant Glossip a stay.

The state again stalled the execution earlier Wednesday, as it awaited the U.S. Supreme Court's response to a last-ditch appeal. The court ultimately denied Glossip's request for a stay of execution by an 8-1 vote. Only Justice Stephen Breyer would have granted the application, according to the one-page court order.

The case of Glossip, 52, is the latest to draw national attention after a series of botched lethal injections put the death penalty under increased scrutiny. A representative for Pope Francis sent a letter to Fallin asking her to commute Glossip's death sentence hours before the scheduled execution.

The seemingly thin evidence that led to Glossip's conviction has also drawn the attention of celebrities such as Susan Sarandon, George Takei and former University of Oklahoma football Coach Barry Switzer.

Here's a look back at the strange path that landed Glossip on Oklahoma's death row.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day's top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

How was Van Treese killed, and why was Glossip convicted if he didn't carry out the attack?

Glossip worked at the Best Budget Inn, an Oklahoma City motel that Van Treese owned, in 1997. Justin Sneed, a janitor at the motel, used a baseball bat to beat Van Treese to death at the motel, but avoided the death penalty by agreeing to testify against Glossip. Instead, he received a life term.

Sneed told prosecutors that Glossip, the motel manager, ordered Sneed to kill Van Treese because he was afraid Van Treese was about to fire him. Glossip, Sneed said, had been embezzling money and managing the business poorly.

Glossip was twice convicted of ordering the killing, once in 1998 and again in 2004, and sentenced to death both times, according to state Department of Corrections records.

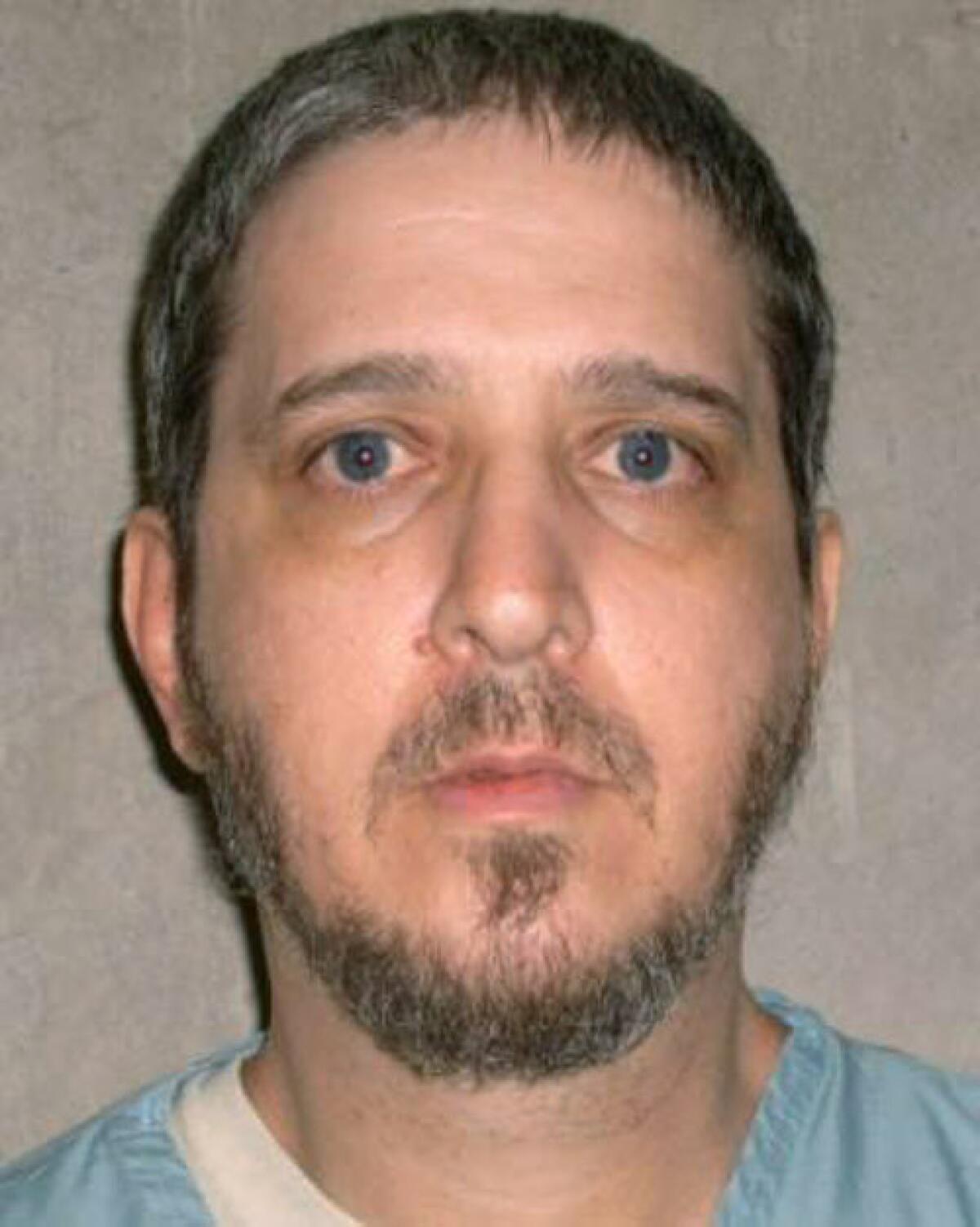

Oklahoma death row inmate Richard Glossip.

Richard Glossip has remained on Oklahoma's death row for more than 15 years. (Associated Press)

The state's case

Prosecutors have long said Glossip arranged for Van Treese to be killed because he feared losing his job.

Van Treese was furious with Glossip over the condition of the motel and because Glossip was not keeping proper records of who had been staying there, a motel employee testified. According to court records, Van Treese also told an employee that he was considering firing Glossip.

So, prosecutors said, Glossip asked Sneed to kill the motel owner.

They said Sneed was completely dependent on Glossip, who was allowing him to stay in the motel and providing him with food in exchange for his services as a handyman on the premises, according to court records.

Sneed told prosecutors that Glossip asked him multiple times to kill Van Treese, finally offering him $10,000 on Jan. 7, 1997, the day of the killing.

Afterward, Glossip told a housekeeper that he and Sneed would take care of cleaning the lower floor of the hotel, according to court records. That’s where Van Treese's body was located.

Criticism of the conviction

Celebrities, opponents of the death penalty and several Oklahoma prisoners have tried to discredit Sneed's version of events. Glossip has maintained that he is not guilty, and his attorneys contend that prosecutors leaned too heavily on Sneed's testimony, which is the only concrete evidence linking Glossip to the killing.

"We know Mr. Glossip did not kill anyone" Glossip's attorneys wrote in an appeal that delayed his execution earlier this month. "The only evidence that he was even involved in a killing comes from Justin Sneed's lips."

The appeal included an affidavit from one of Sneed's former cellmates who quoted Sneed as saying that he had "set Richard Glossip up."

A case summary compiled by Sister Helen Prejean, a famed opponent of the death penalty, also disputes much of the circumstantial evidence raised by prosecutors. Prejean argues that if, as Sneed claimed, Glossip had entered the room where Van Treese died and took money from the dead man's wallet, then Glossip's fingerprints should have been found in the room.

Prejean also has said that Sneed's testimony changed repeatedly during Glossip's multiple trials and appeals.

A host of celebrities have called on Fallin and Atty. Gen. Scott Pruitt to halt the execution and review new evidence, but state leaders have not embraced the idea. "I see no reason to cast doubt on the guilty verdict reached by the jury or to delay Glossip's sentence of death," Fallin said this month.

Early Wednesday, a representative for Pope Francis sent a letter to Fallin asking her to stop the execution. The letter, by Archbishop Carlo Maria Vigano, said a commutation would "give clearer witness to the value and dignity of every person's life."

See the most-read stories this hour >>

The wider debate

Glossip's case is at the center of a larger debate about the drugs used to kill death row inmates in the U.S. After a series of botched executions left inmates gasping for air and writhing in pain in Oklahoma, Arizona and Ohio last year, the U.S. Supreme Court decided to hear Glossip vs. Gross, a challenge to the use of the sedative midazolam, which was used in each of those cases.

Some states switched to midazolam in recent years after foreign pharmaceutical companies began restricting access to pentobarbital, which was often used in lethal injection cocktails. Foreign companies began cutting back on sales because they morally objected to the use of the drug in executions.

Glossip's Supreme Court challenge ultimately failed in late June, when the high court ruled 5 to 4 that Oklahoma and other death penalty states could use the drug. But two of the court's liberal justices also noted they would be open to a legal challenge to the death penalty's constitutionality in the future, meaning Glossip may have opened the door for a separate landmark court case.

The drug cocktail that Oklahoma officials planned to use to kill Glossip led to another delay of his execution late Wednesday. In an executive order, Fallin, a Republican, postponed the execution until Nov. 6 after corrections officials discovered they had received potassium acetate as one of the three drugs to be used in the lethal injection cocktail.

Fallin said corrections officials need to determine whether potassium acetate complies with the state's execution policy, or if officials need to acquire potassium chloride in order to conduct the execution.

Sister Helen Prejean, left, addresses the media outside the Oklahoma State Penitentiary about the case of death row inmate Richard Glossip. With her are two of Glossip’s attorneys, Kathleen Lord and Don Knight.

Defense attorneys Kathleen Lord, center, and Don Knight talk as Sister Helen Prejean, left, speaks to the media outside the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. (Associated Press)

A last legal maneuver

Glossip's execution was delayed earlier this month after his attorneys filed an appeal with the state's Criminal Court of Appeals. His legal team wanted an evidentiary hearing and planned to call several witnesses, including Sneed and his former cellmate, Michael Scott, according to court records.

The state appeals court denied Glossip's motion Monday by a vote of 3 to 2, ruling that most of the new evidence his legal team wanted to introduce simply expanded on previous legal challenges that had already been defeated in prior appeals or at his criminal trials.

Glossip's attorneys petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court on Tuesday morning, but that appeal was rebuffed Wednesday. The lawyers also sent a second letter to Fallin, calling for a 60-day stay of Glossip's execution. In the letter, Glossip's attorneys pointed to a second affidavit they say undermines Sneed's testimony, and highlighted Glossip's struggles with drug addiction at the time of the killing.

"Gov. Fallin, this is the wrong man, and the wrong case to carry out an execution. We know from the outpouring of support that we have seen and from the massive publicity that this case has generated, that the entire world is now watching," the attorneys wrote. "They have passed their verdict in this case and that verdict is not guilty. The world is now watching to see if the state of Oklahoma is actually going to execute an innocent man."

Times staff writer Lauren Raab contributed to this report.

Follow @JamesQueallyLAT for breaking news

ALSO:

Georgia executes woman on death row after several appeals denied

Opinion: Oklahoma should delay the Richard Glossip execution

Court delays execution of Oklahoma man who claims innocence in 1997 killing

UPDATES

4:58 p.m.: Updated with more information about the state's case against Glossip and criticism of the conviction.

2:18 p.m.: Updated with information from an executive order issued by Gov. Mary Fallin delaying the execution.

1:05 p.m.: Updated with the U.S. Supreme Court's denial of Glossip's final appeal for a stay of execution.

12:50 p.m.: Updated with the Oklahoma Department of Corrections' decision to delay Glossip's execution pending a Supreme Court vote.

10:59 a.m.: Updated with information from a letter sent by Pope Francis' U.S. representative to Oklahoma Gov. Mary Fallin.

This article was originally published at 6 a.m.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.