As travel ban goes into effect, debate ensues over who counts as ‘close’ family, and Hawaii files a court challenge

President Trump finally saw his travel ban take effect as U.S. embassies across the globe implemented new restrictions Thursday to block travelers from six predominantly Muslim countries as well as refugees from everywhere.

White House officials tried to assure U.S. residents that there would be none of the disruptions at international airports that occurred the first time the administration tried to enact the ban in January.

But immigrant advocates and civil rights groups said guidelines issued by the government on who would be banned were vague and opened the possibility of chaos as thousands of customs and embassy officials tried to implement the order.

“It’s incredibly confusing,” said Mark Hetfield, chief executive of HIAS, formerly known as Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. “We’re just waiting to see what happens.”

The ban, which took effect at 5 p.m. Pacific time, puts a 90-day pause on travel to the U.S. by nationals of Syria, Sudan, Somalia, Libya, Iran and Yemen and blocks all refugee resettlement for 120 days.

It had been halted by various courts until this week, when the Supreme Court said that it could be put in place with an exception for foreigners with a “bona fide relationship” to American individuals or entities. The court offered limited examples, including students, “a worker who accepted an offer of employment from an American company or a lecturer invited to address an American audience.”

In guidelines issued Thursday, the Trump administration interpreted the order to allow entry of people with “close family” in the U.S., such as a parent, spouse, child, adult son or daughter, son-in-law, daughter-in-law, sibling or in-law parents. It said people with employment and university admission would also qualify.

But it blocked grandparents, grandchildren, aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, cousins, brothers- and sisters-in-law.

That set the stage for a legal showdown over who qualifies as close family.

Late Thursday, the state of Hawaii filed a motion in Honolulu’s federal district court asking a judge who previously ruled against the travel ban to clarify whether the government’s list of unqualified relatives violates the Supreme Court’s order.

Government officials said they based their interpretation on the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act.

But Kevin Lapp, a professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles, said the closest that law comes to defining “close family” is a section that describes “immediate relatives” as children younger than 21, spouses and parents. Those relatives get preference for visas, and the government went beyond that definition with the travel ban rules, he said.

Peter Spiro, a law professor at Temple University, said that “the administration’s definition of family is all over the place.”

He pointed out that the immigration act doesn’t allow preferential treatment for mothers- and fathers-in-law — who were included in the administration’s definition of close relatives — but does give preference to fiances and fiancees — who were initially left off the list and then added in the final hour before the ban took effect.

Caught in the confusion was U.S. citizen Afsaneh Shirazi, a 36-year-old software engineer who lives in San Francisco, whose fiance has been in Iran since November waiting for a visa.

Before the last-minute change, the couple had been thinking about moving to another country to be together.

“It was a hard day and I am a bit relieved now,” she said after it appeared her fiance would not be barred. “I am still worried about administrative processing taking a long time.”

The policy on refugees is another source of confusion.

Refugees scheduled to arrive in the U.S. by July 6 will still be allowed entry. But it was unclear how the order would be applied to thousands of refugees who had been approved for travel but could not get flight reservations before that deadline.

Refugee advocates argue that refugee agencies should be counted as bona fide U.S. connections, allowing resettlement to proceed. But the Trump administration said a refugee’s relationship with a resettlement group by itself was not enough.

“Our understanding is that they are essentially shutting down refugee resettlement,” said Justin Cox, an attorney with the National Immigration Law Center. “... If we can’t work this out, we will be back in court.”

Cox is among a team representing immigrants and refugee groups in a case over the travel ban that the Supreme Court is expected to hear in the fall.

The court, which is also considering a similar case from Hawaii, indicated that its move to partially revive the ban was a temporary compromise before it heard full arguments. Plaintiffs have argued that the ban unconstitutionally discriminates against Muslims.

But the matter could be moot by the fall, because Trump’s executive order says the government needs 90 days to evaluate its vetting procedures before offering permanent proposals to hinder entry from terrorists.

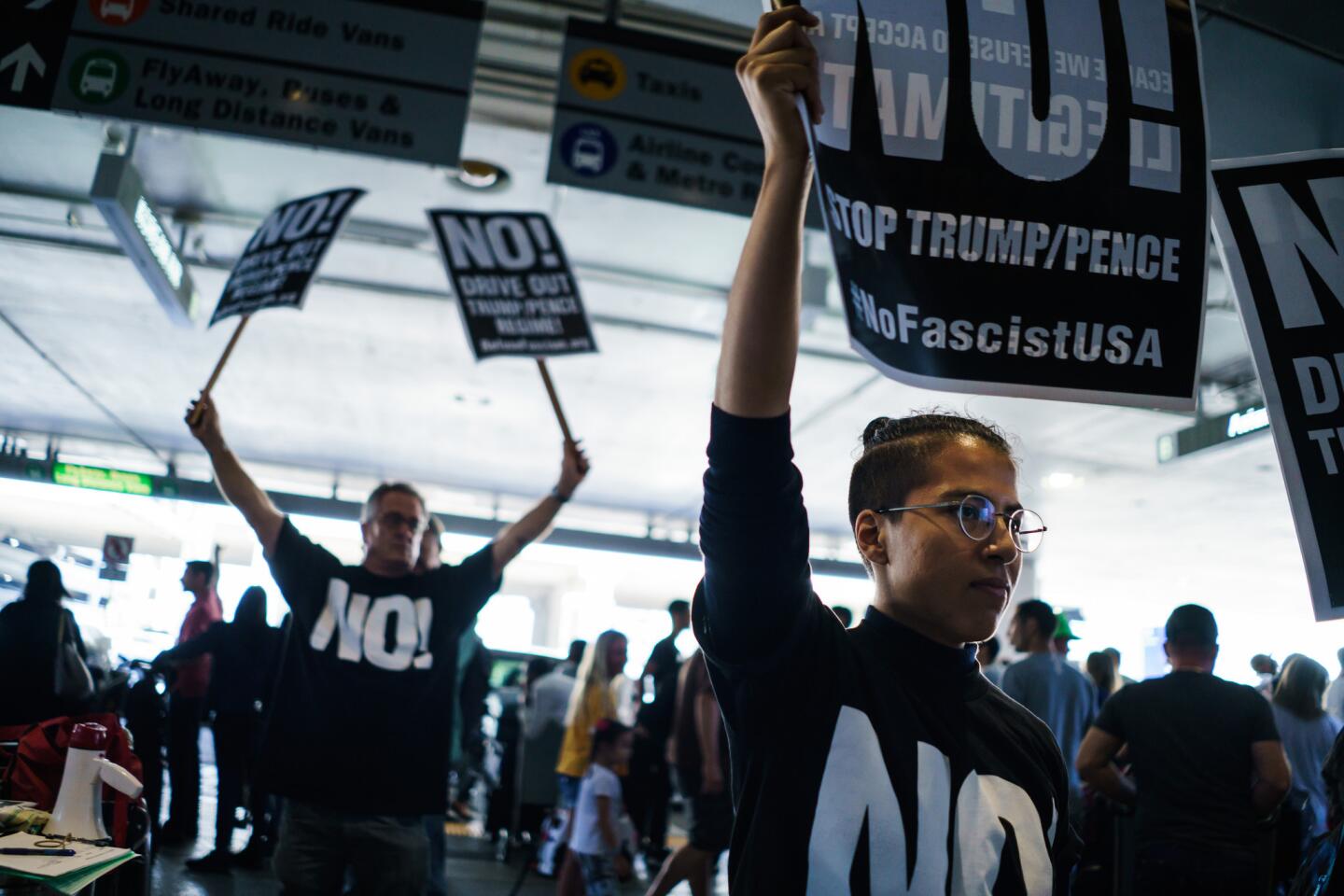

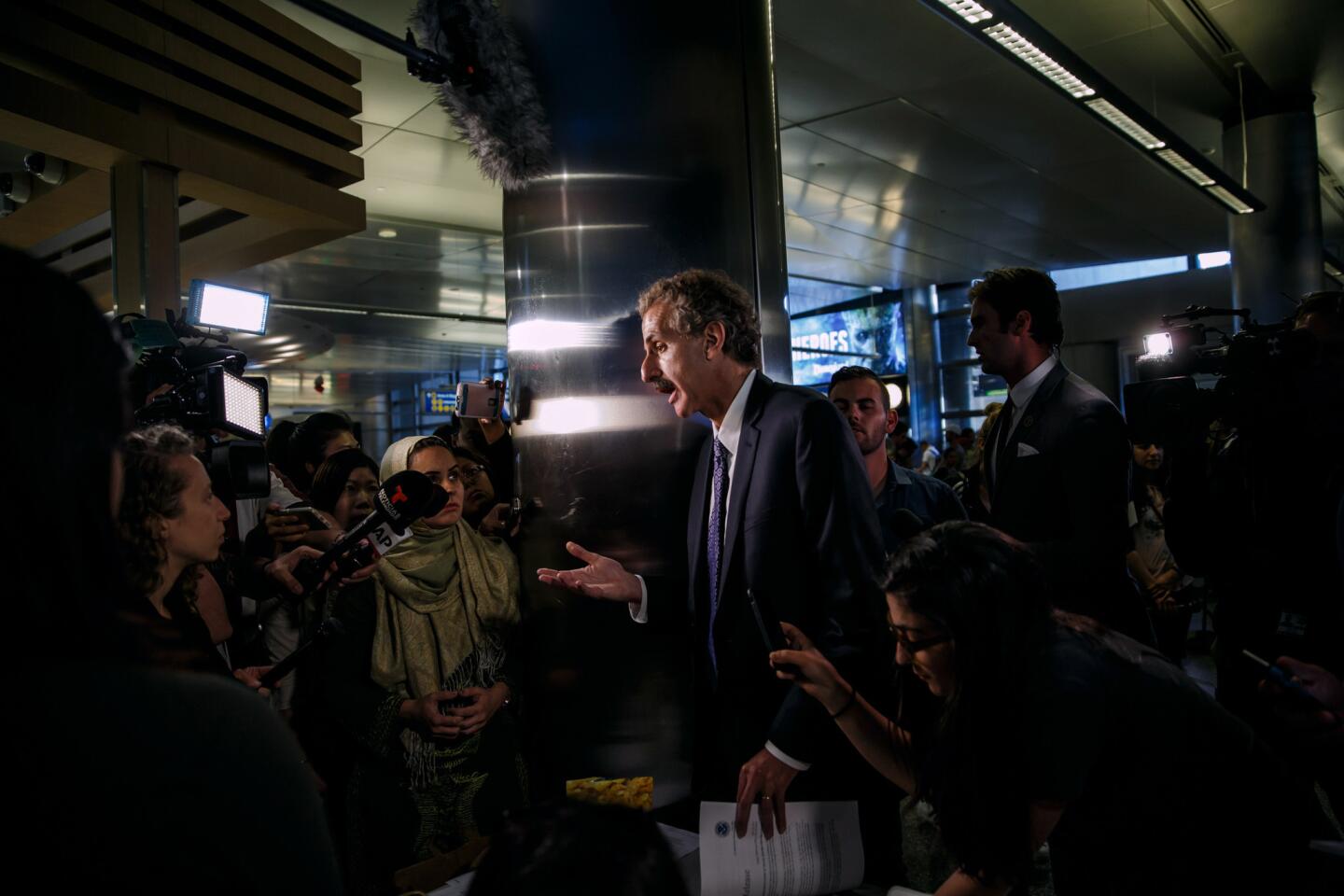

Amid questions about who would be let into the U.S., immigrant advocates dispatched volunteers overnight Thursday to international airports in Los Angeles, Atlanta, New York, Washington and other cities.

“You have kids out of school who expected to see their grandparents this summer,” said Camille Mackler, director of legal initiatives at the New York Immigration Coalition, who was stationed at John F. Kennedy International Airport. “You have U.S. citizens who were planning to get married and can’t bring over their fiances.”

Mackler said she didn’t expect a repeat of the “dramatic scene” that occurred in January when the original ban led to several days of deportations, detentions and thousands of visa cancellations before it was struck down in court.

The chaos led to dozens of lawsuits and months of rants from the president against district and circuit courts that ruled against him.

Trump administration officials said that people who had visa appointments at embassies and consulates should still apply for travel and would be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. They also said consular officials, as before, would have the ability to waive restrictions in individual cases.

Immigrant groups have continued to register their opposition to the ban. The National Iranian American Council said its implementation represented a “new low” by “targeting grandparents of American children.”

“The Iranian community, many of us are first or second generation,” said Jamal Abdi, the group’s policy director. “A lot of our families are still in Iran. A lot of our aunts and uncles are still in Iran…. Many of us can’t go to Iran — now, we see both governments punishing the people who are stuck in the middle and that means families are now being torn apart.”

Nihad Awad, executive director of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, said in a statement that the new travel rules were wrong in “arbitrarily dividing American Muslims from their grandparents and other close relatives overseas.”

“These illogical rules must not stand, nor should any other part of the discriminatory and unconstitutional Muslim ban,” he said.

Times reporters Melissa Etehad and Sarah Parvini in Los Angeles, Tracy Wilkinson in Washington, D.C. and Barbara Demick in New York and special correspondent Jenny Jarvie in Atlanta contributed to this report.

ALSO

Q&A: Trump scores a partial win for his travel ban. What comes next?

Editorial: Trump’s travel ban is back, but it’s still as bad a policy as ever

UPDATES:

6:15 p.m.: This article has been updated to include a legal challenge from the state of Hawaii and the addition of fiances and fiancées to the list of close family members who will not be banned from entry.

5:27 p.m.: This article has been updated to include legal analysis and reaction from immigrants and their advocates.

This article was first published at 10:20 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.