Texas gunman’s long slide to mass murder began when he attacked his own family

Reporting from New Braunfels, Texas — Some of those who grew up with Devin Kelley in this sprawling city northeast of San Antonio had seen him change over the years — once just an outsider, he suddenly seemed hostile and argumentative. He wanted to talk about atheism and guns.

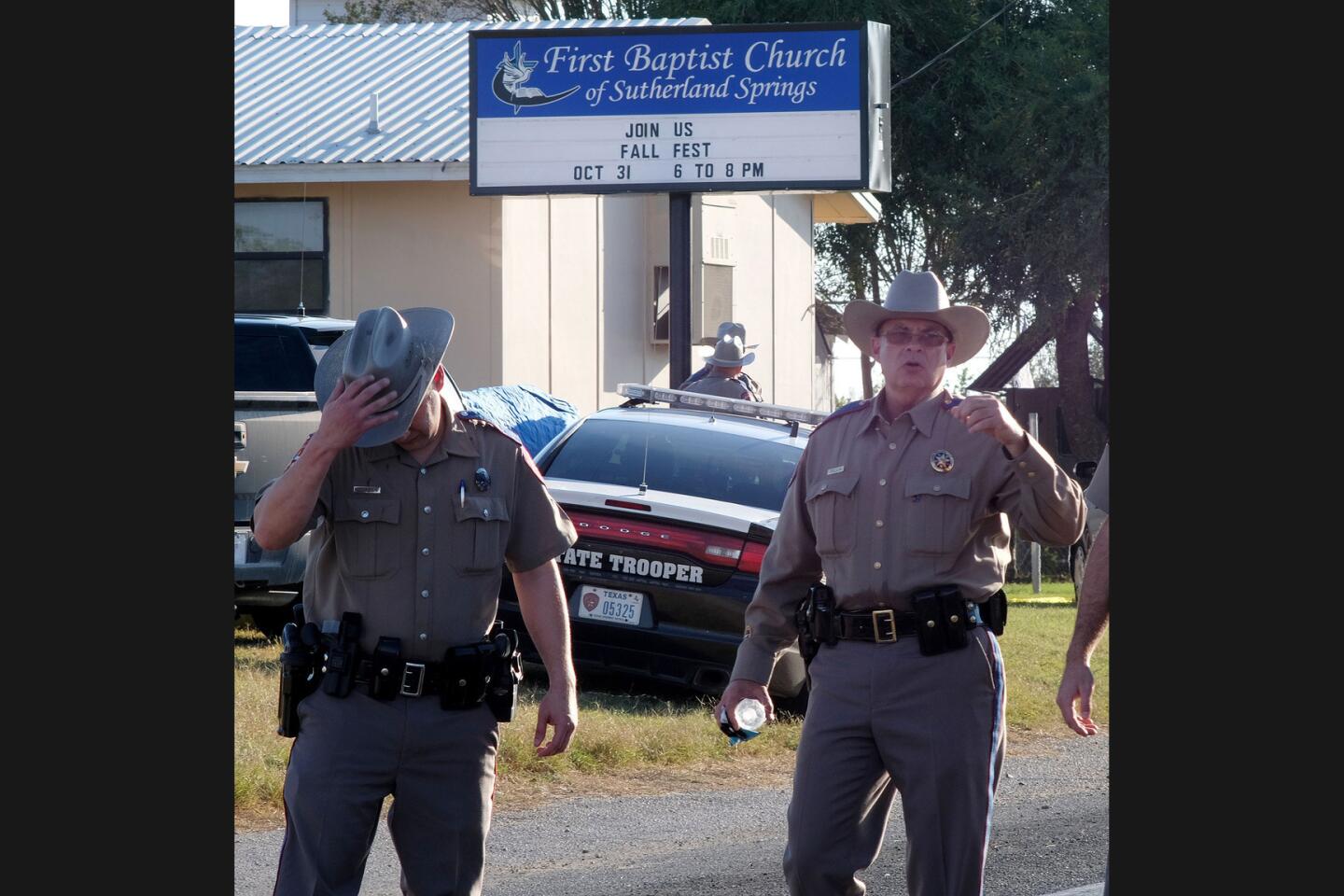

On Monday, a day after authorities said Kelley opened fire in a small church 35 miles south in Sutherland Springs, killing 26 people, there were feelings of shock and sadness here in his hometown, but not necessarily surprise.

“He wasn’t always a ‘psychopath,’ ” Courtney Kleiber, a classmate of Kelley’s at New Braunfels High School, wrote on Facebook. “Though … over the years we all saw him change into something that he wasn’t. To be completely honest, I’m really not surprised this happened, and I don’t think anyone who knew him is very surprised either.”

Former classmates remembered Kelley as an outsider who seemed to have gotten darker after high school. Some said they had blocked him on Facebook after receiving inappropriate notes or tiring of antagonistic posts.

“All atheism and gun posts,” Reid Mosis wrote. “Nothing that led me to think he was about [to] do anything close to this, though.”

“It wasn’t until after high school that he changed and got super creepy,” Emily Elizabeth Robb wrote, noting that she and her friends would talk about the messages Kelley would send them. “Ugh.”

Serving in the Air Force from 2010 to 2014, Kelley showed signs of mental illness, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott told ABC’s “Good Morning America.” He was “a very deranged individual,” he said.

While stationed at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico in 2012, Kelley assaulted his stepson so severely he fractured his skull and also attacked his wife, Tessa. He was charged with two counts of assault, one aggravated.

He admitted striking his wife, choking her, kicking her and pulling her hair, and striking his stepson on the head and body with a force “likely to produce death or grievous bodily harm,” according to military documents.

“For his stepson, it was serious enough that he had broken bones, skull fractures and bleeding on the brain,” said Don Christensen, a retired colonel who was the Air Force’s chief prosecutor. “His son was shaken violently on more than one occasion.”

In November 2012, Kelley was convicted of two charges of domestic assault and sentenced to 12 months in confinement at Naval Consolidated Brig Miramar in San Diego. His first marriage ended in divorce.

He married Danielle Lee Shields, who came from Sutherland Springs, before he left the Air Force on a bad-conduct discharge in April 2014.

Even before they wed, there were signs of problems. In February 2014, sheriff’s deputies were called to Kelley’s parents’ house in Comal County, Texas, to investigate a potential domestic violence case after Danielle complained to a friend of abuse. They were married two months later.

After the couple moved into a mobile home park in Colorado Springs, Colo., Kelley was charged with misdemeanor animal cruelty when a woman complained that he had beaten and dragged his Husky puppy, according to the Denver Post.

“She stated the white male then began punching the dog with a closed fist near the head and neck area,” according to an August 2014 El Paso County deputy report. “She stated she witnessed four to five punches and then the male suspect grabbed the dog by the neck and drug him away.”

By 2017, Kelley had moved back to Texas to live with his parents in the sprawling, 3,711-square-foot home with a swimming pool where he grew up, located on a rural stretch of rolling brushland dotted with prickly pear cactus.

His family lived a comfortable, upper-middle-class life, with his father running a software company that specializes in billings. On the company’s website, Michael Kelley wrote that he and his high school sweetheart moved to the countryside in 1993 to raise their children, of whom Devin was the middle of three.

“Building the company at the same time as our family involved a whirlwind of activity,” he wrote. “Lots of late hours and sacrifice.”

In the last two months, neighbors said they had heard bursts of rapid-fire shots coming from the direction of the Kelley home.

“It was like bop, bop, bop, at random times of the day,” said Gerald Killough, 52, who lives just around the corner. He had never met Devin Kelley or his parents. “People move out here for their privacy,” he said. “You just mind your own business.”

Kelley took a summer job as an unarmed night security guard at Schlitterbahn, a local water park and resort, but he was terminated after just five-and-a-half weeks.

“He was not a good fit,” said Winter D. Prosapio, corporate director of communications at the company.

At the time of Sunday’s shooting, Kelley had worked five weeks at another nighttime security job at Summit Vacation Resort and RV park, a pastoral spot near the Guadalupe River, about 10 miles from his parents’ house.

Working a 4 p.m.-to-midnight shift — mostly alone — he attracted little attention. The only thing anyone seemed to notice was that he didn’t talk much.

“There were no warning signs,” said Claudia Varjabedian, the office manager, who did not realize Kelley was the church shooter until about an hour after he failed to show up for his Sunday shift. “He was very quiet. We didn’t know him.”

Before attacking the church on Sunday, Kelley had sent threatening text messages to his mother-in-law, who sometimes attended the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, officials said. She was not in attendance when Kelley entered the church Sunday.

Across New Braunfels, flags flew at half-staff Monday outside churches, RV parks and gun stores.

Outside the Kelley family’s home, police cars were parked in front of a cattle gate. It bore a sign: “No trespassing.”

Jarvie is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.