The great test for Trump’s border wall: Texas’ Rio Grande Valley

The moon narrowed to a sliver as several migrants paddled a raft across the Rio Grande to the banks of this small Texas border town and scrambled up well-worn dirt trails through thorny mesquite into a cluster of shabby houses.

There was no wall to stop them. That job fell to half a dozen Border Patrol agents on bicycle and foot patrol last month. Flashlights bobbing, the agents found a pregnant Central American migrant stopped by a Family Dollar parking lot. She surrendered in hopes of applying for asylum. The others had disappeared.

“We do not have control,” said Manual Padilla Jr., the Border Patrol’s sector chief for the Rio Grande Valley. In the area around Roma, he said, traffic has shifted to where the agency does not have sufficient personnel, technology and infrastructure — including a wall.

But where and how to build the wall? That’s the complicated question in the Rio Grande Valley, the busiest stretch of the southern border for migrant apprehensions and marijuana seizures.

When Congress in March approved $1.6 billion for border wall and fencing, it covered 100 miles of barriers in California, New Mexico and Texas. The largest stretch — 33 miles — is expected to rise later this year in the Rio Grande Valley and have the most potential to deter immigrants and drug smugglers. But it’s still not clear where the limited barrier will go.

“Locations … are operationally driven,” Border Patrol officials said in a statement, noting that the agency “considers strategic objectives, border census data, and the feasibility of constructing physical barriers along the border.” Agency officials and experts analyze that material and additional factors — such as risk and intelligence — to decide where to build.

The land along the Rio Grande is perhaps the trickiest stretch of new wall to build. The river winds for 350 miles, and with it the border, a floodplain where construction is restricted by water treaties with Mexico. Residents and businesses own property south of existing border barriers, land that’s still legally part of the U.S., so the Border Patrol adds entrances to allow agents and landowners access south of the wall.

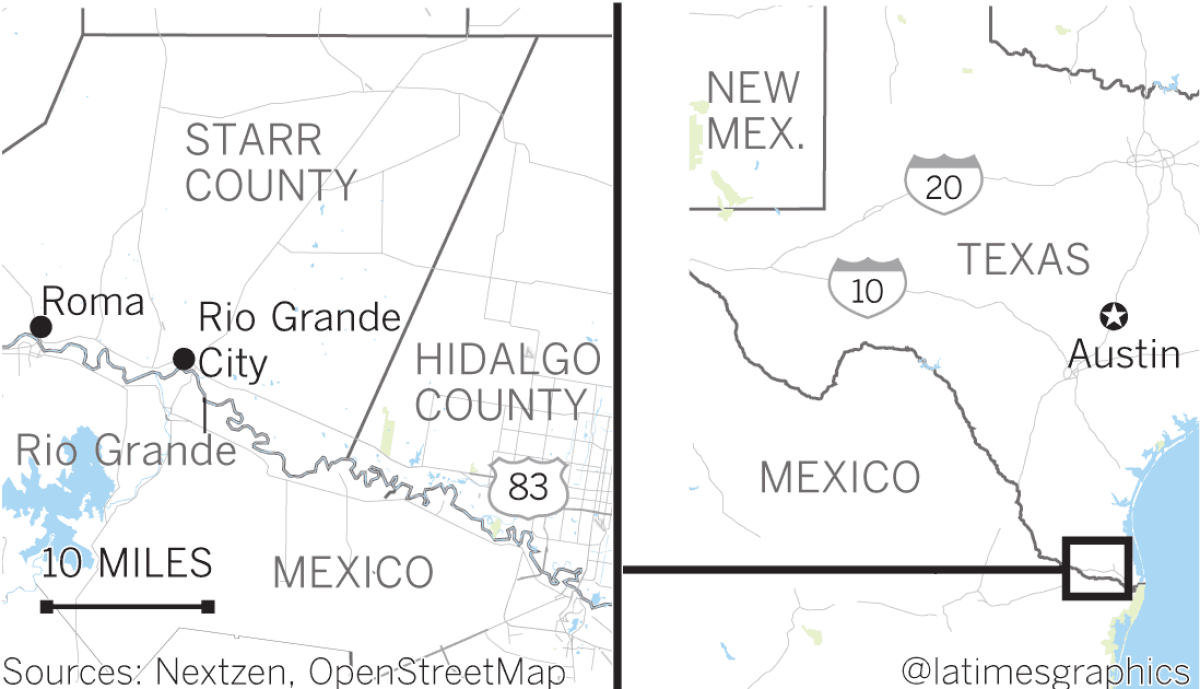

Officials have not released maps of where the new wall will be built, but confirmed that it will be erected in adjacent Hidalgo and Starr counties.

In these counties, Border Patrol agents’ radios are usually abuzz before dawn. One morning last month east of Roma in Starr County they caught a dozen men crossing the river, a family of two in a nearby park, and were about to catch another eight men across from a section of unfenced border — all before 8 a.m.

Agents fanned out north of the river in Hidalgo County on well-worn smugglers’ trails through shoulder-high nopal cacti. They chased the men, a mix of Mexican and Salvadoran migrants, tackled and cuffed them.

“This is the busiest sector in the nation,” Agent Robert Rodriguez said after the chase. “So this is a normal thing.”

In Hidalgo County, 25 miles of fencing will be built atop levees at a cost of $445 million, blocking access to the river except for a three-mile stretch at the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge, where the Sierra Club and others had opposed a wall. Requests for proposals are being issued for wall designs, and Border Patrol officials have already held several meetings with at least one landowner to make accommodations, such as adding concrete irrigation sleeves and enlarging wall gates for farm equipment.

In Starr County to the west, eight miles of similar bollard fencing will be built atop concrete wall at a cost of $196 million. The Border Patrol has yet to determine where the fence will be built, according to Loren Flossman, director of the agency’s Air and Marine Program Management , who has coordinated border wall building for more than a decade. If the project comes in under budget, they may build more wall in Starr County, he said.

“The Rio Grande has a set of challenges nowhere else has in that the wall is not on the border, and there’s some homes we have to accommodate access to,” Flossman said.

Flossman said officials were still doing hydrological studies “to see if there’s a rise in water in the Rio Grande, so that whatever barrier we have does not deflect water into Mexico,” in violation of international treaties. He said it wasn’t clear whether the wall would rise in Roma or farther west in less-inhabited areas.

Flossman makes the final wall-building plans after consulting with Border Patrol officials and local residents. He takes into account possible conflicts with landowners, prioritizing areas where the government can build more easily.

“Where we would start is where the government has an interest and there aren’t other private owners involved,” Flossman said.

Flossman met with valley residents and community groups this month to discuss plans and arrange rights of entry to survey properties now that Congress has funded construction. Such surveys are required to start environmental, design and real estate plans.

“Before, we didn’t have a budget and couldn’t say what we would be doing. Now we can,” he said.

Officials say more walls are needed but acknowledge their limitations.

“We think it will make a big difference here,” said Rio Grande Valley Border Patrol Deputy Sector Chief Raul Ortiz. He added, however, that “when you place infrastructure in one area, it pushes folks to areas where you don’t have that.”

Agents call the phenomenon “the water balloon effect.” Ortiz said the agency plans to secure spaces between the wall with technology like aerostat blimps and towers.

“We’re just not going to leave gaps,” he said.

Rep. Henry Cuellar, a Democrat, said he hopes residents’ feedback is taken into account.

“As someone who has represented border districts for years and years, I understand how my constituents will be directly impacted by the proposed construction of border walls. Border communities like Hidalgo County and Starr County will lose their property, and lives will be disrupted for no other reason than for political theatre,” Cuellar said. “The administration should view border communities and stakeholders as active participants in this process, not as spectators.”

Scott Nicol, co-chairman of the local Sierra Club’s borderlands team, met with Border Patrol officials about wall plans and said the agency seemed to want to build as quickly as possible, regardless of whether the barrier serves a tactical purpose. Opponents persuaded officials not to build in the Santa Ana refuge, and now they’re trying to stop construction at other refuges, including a popular butterfly center.

Nicol said the Border Patrol needs to release maps of potential wall locations in Starr County. “All the people in the path of that deserve to know,” he said. “People deserve to be able to plan.”

The Border Patrol released maps last summer that showed new stretches of wall to the east of Roma in Los Ebanos, a river outpost of several hundred where landowners who would be stuck to the south of a barrier already sued to block the wall.

Shaded by its namesake ebony trees, Los Ebanos is home to a small border crossing served by a hand-drawn ferry founded in 1950, now the last of its kind on the Rio Grande.

Border Patrol boats cruised by the ferry one recent day, as an agency helicopter and aerostat hovered overhead. They’re reassuring sights for resident Sulema Munoz Cantu, who credits agents with decreasing the flow of migrants through town in recent years.

Munoz, 65, and her husband would rather see more agents sent to patrol the area than a wall, which they said won’t stop smugglers.

“It’s nonsense,” said husband Israel Cantu Amador, also 65. “Iron gates, wooden gates — they’re going to come through.”

In Roma, Noel Benavides also opposes the wall that may cross his land.

The federal government already condemned a mile-long, 60-foot-wide swath of his property north of the river after the Secure Fence Act passed in 2006, the last major border building project. The land had been deeded to the Benavides family as part of a Spanish land grant in 1767.

But construction on the wall never started. Benavides still hasn’t heard whether the new wall would be built on his property.

Walking the tract, Benavides said that a wall would be a logistical nightmare in the floodplain, that the Border Patrol would be better off investing the money in manpower. He attended local meetings of the Sierra Club, slapped “No Wall” stickers on his pickup truck and at his western wear store. If the government moves to start construction on his land, he plans to hire a lawyer to stop them.

“I believe in our nation’s safety as much as anyone else — maybe more because I see it every day,” Benavides said. But he also believes a short stretch of wall would not stop the border traffic. “It’s going to go somewhere else.”

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.