3 brothers in south Texas, one a Border Patrol agent, charged in drug cartel-linked murder case

Reporting from SAN JUAN, Texas — Joel Luna seemed an ideal Border Patrol hire: south Texas native, high school ROTC standout, Army combat veteran.

Luna worked out of a border checkpoint about 100 miles north of Mexico in Hebbronville, patrolling ranch land frequented by smugglers of humans and drugs. The covert work drew upon his infantry experience.

But now Luna, 31, is preparing to stand trial on a charge of capital murder for his role in what prosecutors say was a cartel drug trafficking conspiracy that left a decapitated corpse floating off the Texas coast during spring break.

To hear prosecutors tell it, the conspiracy is a tale of three Lunas — brothers Joel, Fernando and Eduardo.

Fernando, also known as “Junior,” is the oldest—35, heavyset and bespectacled. The youngest is 25-year-old Eduardo, who sports a shaved head and goatee and goes by “Pajaro,” or “Bird” — a nickname that would play a key role in the case.

Prosecutors say Joel helped Fernando and Eduardo run a criminal family business.

Joel’s attorney says he didn’t kill anyone, that in a region where cross-border families often include a mix of law enforcement and immigrants, it’s Fernando and Eduardo, Mexican citizens in the U.S. illegally, who are to blame for the slaying.

“There’s an argument to be made against my client that’s guilt by association. People get swept up with those who are really guilty. It’s family,” said Joel’s attorney, Carlos A. Garcia. “Associating or going to a quinceañera is not a crime. He was just a family man, a working man. Think about how many Border Patrol members who live on the border have relatives here without visas.”

According to his U.S. birth certificate, Joel was born in San Juan, less than 10 miles north of the Rio Grande, but he was raised south of the border in Reynosa, a Gulf cartel stronghold. Fernando and Eduardo were born in Mexico.

The boys’ parents obtained a Mexican birth certificate for Joel so that he could attend elementary and middle school in Mexico, Garcia said. “This is a common thing along the border. Joel was no different. People who are born here, their families take them into Mexico to attend school up until high school, until they have to pay for it,” he said.

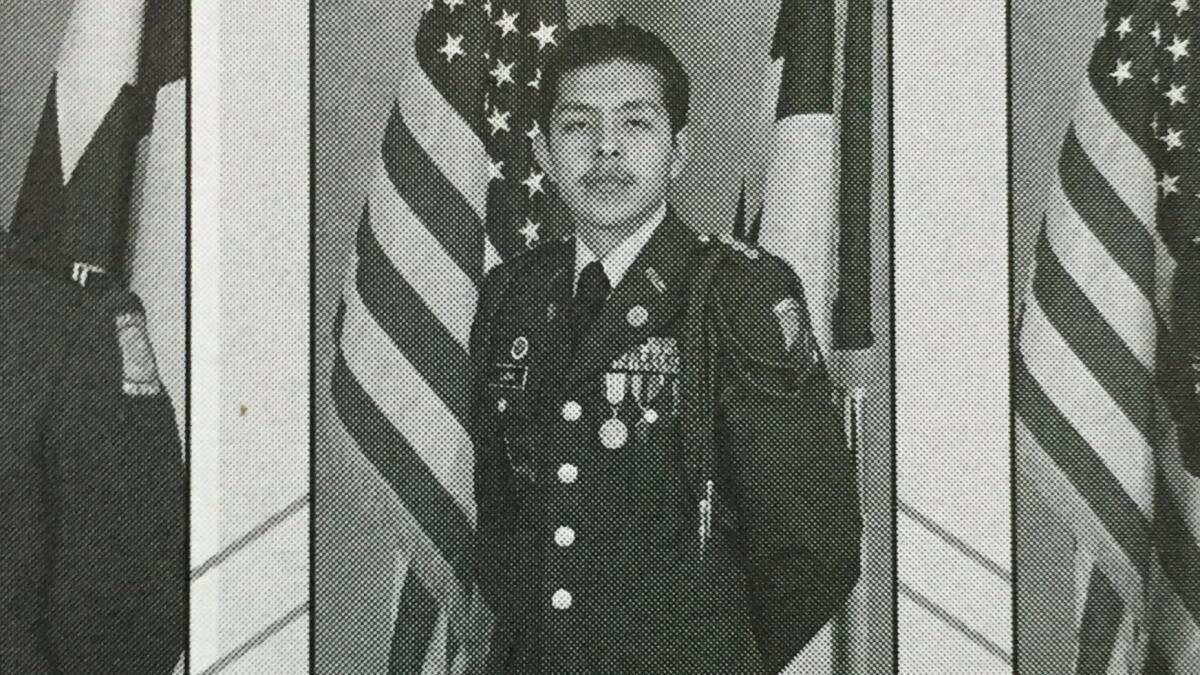

Thanks to his U.S. birth certificate, Joel attended Pharr-San Juan Alamo High School, joined Army ROTC, and became a commander. Yearbook photos show him running laps and posing in uniform, a short, trim figure trying to look serious with the shadow of a mustache.

“He knew what he wanted to do from a young age,” Garcia said. “He wanted to defend his country.”

After graduating, Joel joined the Army in 2004 and served a combat tour in Iraq. In 2008, he was discharged as a specialist to the Army National Guard, serving for four more years in the Rio Grande Valley.

When he joined the Border Patrol in 2009, Joel underwent a background check but was not required to take a polygraph test: It would become mandatory the following year under the federal Anti-Border Corruption Act.

Joel married a local girl, Dulce “Candy” Trevino, now 31, who worked at a doctor’s office, and they soon had a girl and a boy. They drove a Chevy pickup and two SUVs, and shared a three-bedroom ranch house next to his mother-in-law’s at the edge of town where roosters crowed at dawn.

While Joel was building a career, across the border in Reynosa, Fernando worked at Exterran Corp., an oil and gas company, and Eduardo began associating with the Gulf cartel, investigators allege.

It was recently revealed in court that a high-ranking Gulf cartel figure now locked up in Houston told prosecutors he served alongside Eduardo as a cartel “comandante.” One day, Eduardo accompanied Joel to a south Texas Sam’s Club and bought a black steel safe, Joel’s brother-in-law told investigators. Joel kept the safe at his mother-in-law’s house.

In 2013, Joel notified Border Patrol officials that Eduardo had been temporarily abducted by cartel leaders in Reynosa who knew Joel was an agent and had threatened his family there, according to Cameron County Assistant Dist. Atty. Gustavo “Gus” Garza.

Eduardo, Fernando and their families crossed into the U.S. illegally to live at Joel’s house. Luna gave his sister-in-law $42,000 and instructed her to buy a house in San Juan for his younger brother, according to an arrest affidavit. Fernando moved in across the street, Garza said.

Fernando had been laid off and used severance pay to buy Veteran’s Tire Shop, about 20 miles north in Edinburg, according to an affidavit. He hired Eduardo and kept three other employees. Investigators would later argue that the run-down shop, like other businesses in south Texas, was a front for money laundering and drug trafficking.

Joel, meanwhile, projected a law-abiding image. Jose Luis Villanueva, 53, Luna’s wife’s stepbrother, described him as “calm, hardworking,” a quiet presence who never did drugs or even drank alcohol around family.

On March 16, 2015, a boater cruising with his daughters off the coast of South Padre Island spotted a nude, partially decomposed body and called 911. Investigators never found the man’s head, but identified him as one of Fernando’s employees: Jose Francisco “Franky” Palacios Paz, a 33-year-old Honduran living in the U.S. illegally.

Fernando and Eduardo agreed to let investigators search their cellphones. The phones had been erased, but according to an arrest affidavit, investigators recovered text messages Palacios’ wife sent to Fernando the day before the Honduran migrant disappeared.

“This Franky is a ... traitor,” she wrote in Spanish, complaining that Palacios was talking “about drug sales.”

“At any moment he is going to put the finger on you,” she wrote.

Investigators’ records also show that the day Palacios went missing, Eduardo and one of the tire shop workers drove to Port Isabel, just across the causeway from where the headless body was found; their cellphones pinged nearby towers as they called Fernando.

A pickax and stains at the tire shop tested positive for Palacios’ blood. One of the other employees told investigators that Palacios’ head was taken to Mexico to be displayed publicly, or “demonstrated,” a cartel ritual, Garza said.

On June 24, 2015, investigators arrested Eduardo and two shop employees. Fernando was arrested as he was returning from Mexico — in Joel’s white pickup. But Joel was not charged, and remained on the job with the Border Patrol.

Four months later, sheriff’s and Homeland Security investigators raided the house of Joel’s mother-in-law and said they found the black safe containing what would become the basis of their case: more than a kilo of cocaine, more than $89,500 in bundled cash, and a 1911 silver-plated .38 pistol embossed with the gold image of St. Jude, engraved with the words “Cartel del Golfo” and “pajaro” — Eduardo’s nickname.

A ledger documented the sale of drugs, guns and ammunition. Most damning of all, authorities said, was a commemorative Border Patrol badge and documents belonging to Joel Luna, including his work station password and Security Service Federal Credit Union account number.

Joel said he “had no knowledge of the safe,” according to investigators’ dash camera video. He was arrested on various charges, including tampering with evidence and capital murder. In his mugshot, he looked weary.

In January, a grand jury indicted the three Luna brothers on capital murder for retaliation charges, along with the two workers. They all pleaded not guilty.

But last month, Fernando, the eldest brother, pleaded guilty to drug possession in exchange for agreeing to testify for the prosecution. Prosecutors dropped criminal conspiracy and murder charges, and he faces a maximum of three years in prison at sentencing Oct. 19.

Eduardo still faces trial. So does Joel.

Joel’s attorney said the once-promising ROTC commander and Border Patrol agent has declined a plea agreement and will take his chances before a jury.

“The state’s case is built on conjecture and speculation. My client doesn’t have anything to fear from what his brother will say,” Garcia said, adding that he is fighting to have Joel and Eduardo tried separately. Eduardo’s attorney did not return calls or email.

“My client should not be held to account for his brother’s acts,” Garcia said.

Garza, the prosecutor, has his own theory of what happened to the Luna brothers. Their father had died, and Garza suspects Joel felt obligated to help his brothers at first.

“That happens in families all the time,” Garza said. “After that, he was more and more involved. He was up to his ears.”

Twitter: @mollyhf

To read the article in Spanish, click here

ALSO

After Texas high school builds $60-million stadium, rival district plans one for nearly $70 million

New York explosion that injures 29 is called an intentional act, but no link to terrorism is seen

Pocket constitutions and upside-down flags: Ammon Bundy supporters get their week in court

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.