Without elephants, the circus couldn’t go on, Ringling Bros. officials say

Reporting from Palmetto, Fla. — Executives with the parent company of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus said Monday that a decision to remove elephants from the show in response to pressure from animal rights groups instantly affected ticket sales, leading to the decision to close the 146-year-old company.

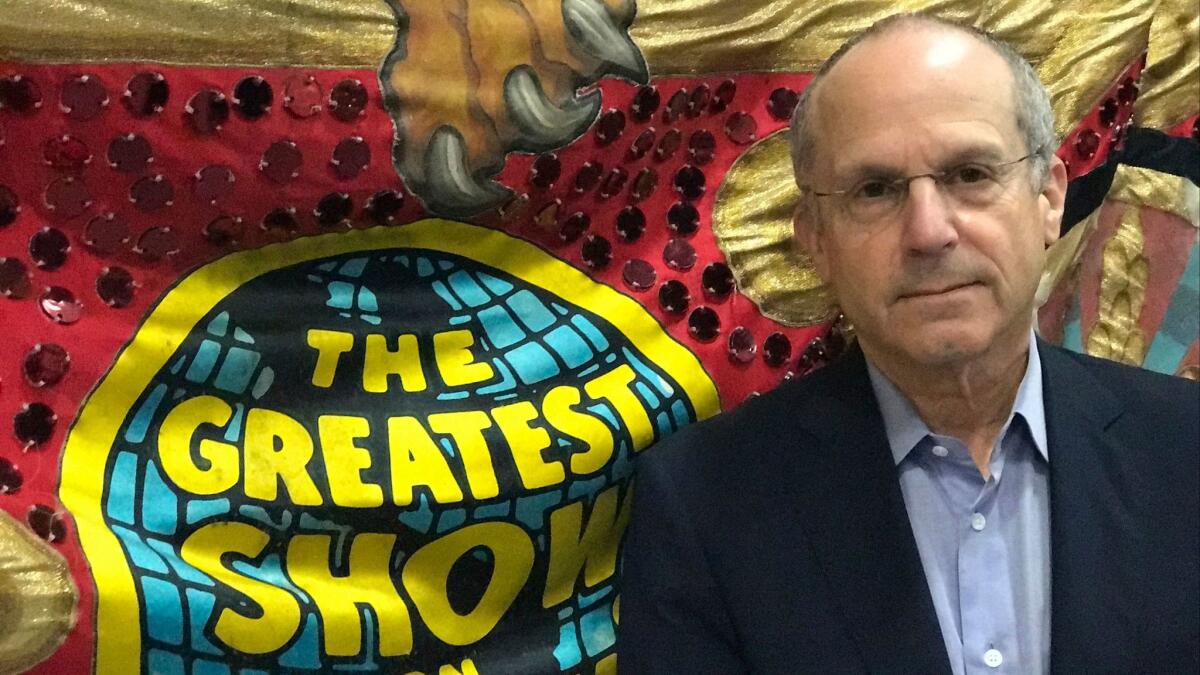

“Since last May, when the elephants were taken off the show, the downward trend was much more severe than had been anticipated,” Kenneth Feld, chairman and chief executive of Feld Entertainment, said at a news conference at the company’s headquarters. “Over the past eight or nine years there’s been a decline, but when the elephants left the show we did not anticipate the impact that would have.”

Feld, along with his daughter and chief operating officer, Juliette Feld, said roughly 60 animals — including tigers, lions, donkeys, alpacas, kangaroos, dogs and horses — would be affected by the closure of “The Greatest Show on Earth,” and more than 400 employees would lose their jobs.

The company announced Saturday night that it was planning to close.

Asked Monday if the shutdown was a victory for animal rights activists, Kenneth Feld paused, then said, “This is not a win for animal rights activists nor is it a win for anyone … because they’re going to have to find some new way of fundraising, I suspect.”

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals issued a statement celebrating the demise of what it called “the saddest show on Earth.”

“All other animal circuses, roadside zoos, and wild animal exhibitors, including marine amusement parks like SeaWorld and the Miami Seaquarium, must take note: Society has changed, eyes have been opened, people know now who these animals are, and we know it is wrong to capture and exploit them,” PETA said.

Feld spoke about the lawsuits through the years accusing his company of inhumane animal training practices.

“We prevailed in court 100% of the time,” he said. But, he added, “obviously, in the court of public opinion we didn’t win.”

The two executives were asked whether they had seen the writing on the wall months before. They had been trying a variety of changes to modernize the show and compensate for the loss of the elephants, Kenneth Feld said, but nothing helped.

Though the battles with animal rights groups were clearly difficult for Ringling to absorb, there also was a sense that the traditional circus — once a central facet of American popular culture in a pre-television, pre-Internet age — had simply outlived its time.

“Today the circus is not in the daily vernacular as it was before,” Feld said.

The CEO said the company would provide severance packages to its employees, along with help finding housing and jobs. The animals still owned by the circus will be provided with care until suitable homes are found for them over the next few months, Juliette Feld said.

Among the equipment being divested: two trains, each a mile long, that the company owns to transport performers, crew and equipment on tours throughout the country.

For decades, animal rights activists targeted the circus, saying it used “dominance training” to break the elephants’ spirit.

“The only reason that an animal like that — of its size and intelligence — would do what they do in circuses is because they would have experienced severe pain and become scared of the man training them,” said Susan Nance, a historian of U.S. show business at the University of Guelph, in Canada, who has written extensively about how circus elephants are managed.

However, a lawsuit filed by a consortium of animal rights groups against Ringling Bros. was ruled to be frivolous, and two of the groups — the Humane Society of America and the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals — ultimately agreed to pay the company a total of roughly $25 million to settle the case.

Still, the animal rights campaigns and a shift in cultural perceptions about the use of animals in circuses ultimately proved too difficult for the company to overcome.

“The show was so stubborn for so long about the elephants,” Nance said. “Even though they won all those lawsuits, I just wonder if they didn’t start to tarnish the brand — so much so that people just started saying, ‘You know what? I don’t want to go see Ringling.’”

Neuhaus is a special correspondent.

ALSO

Who needs the circus when you’ve got politics? Reaction to the pending closure of Ringling Bros.

How these Los Angeles-born pink hats became a worldwide symbol of the anti-Trump women’s march

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.