How MLK’s death affected a nation, as told by those who remember it

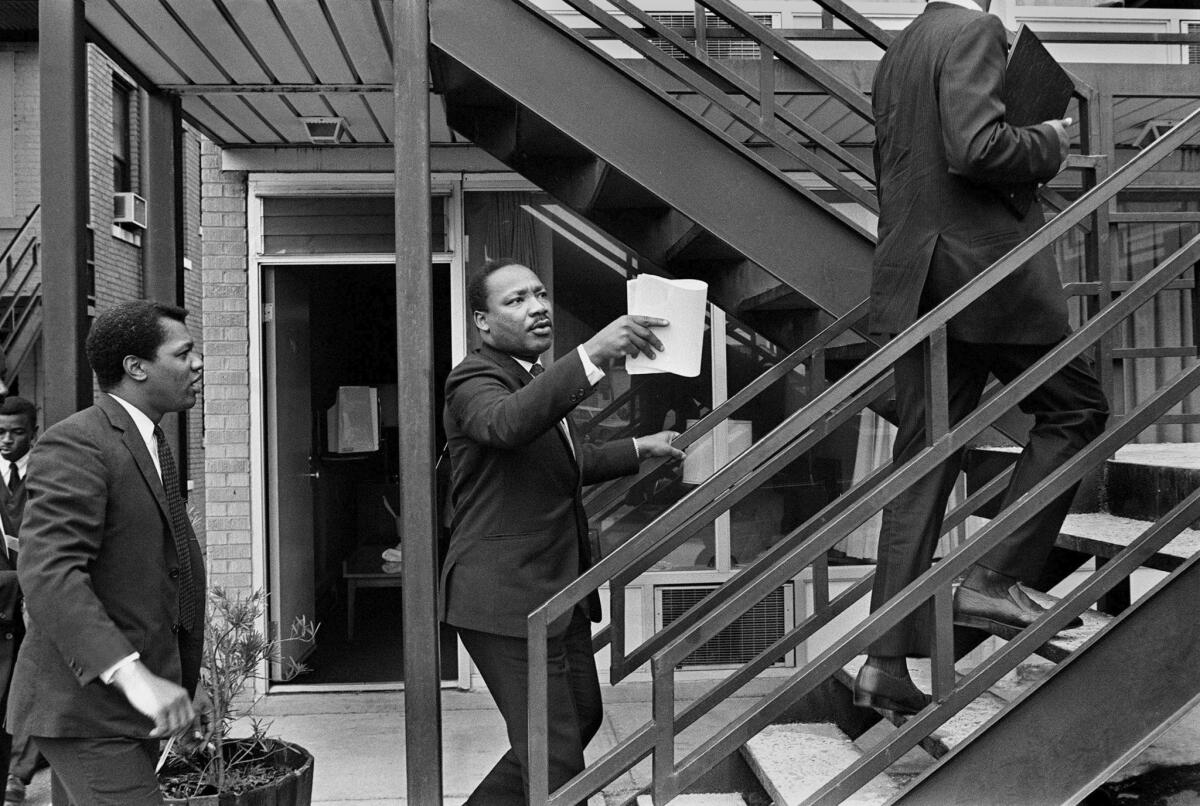

Martin Luther King Jr. had traveled to Memphis, Tenn., in late March 1968 to lead a protest march in support of the city’s striking sanitation workers. Violence had followed, with police descending on the protesters with billy clubs, mace and tear gas.

The next week, King returned to get court permission for another march. Despite the death threats he had received, and the growing concern for his safety, King pressed to hold a nonviolent demonstration.

On the night of April 3, he delivered what became known as the “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech, in which he said:

“Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I have looked over, and I have seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!”

The events of the next day, April 4, 1968, would be seared into the memories of Americans for decades.

Do you remember King's assassination? Leave your memories in the comments section.

A fallen King

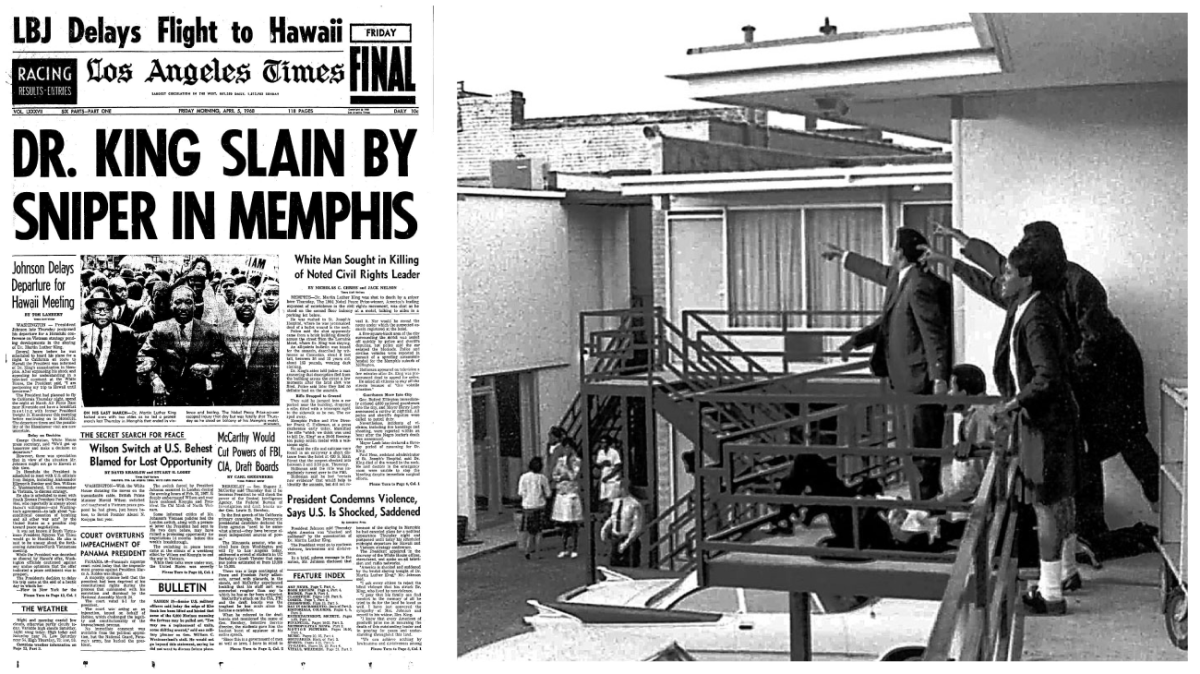

The bullet struck him just before dinner time.

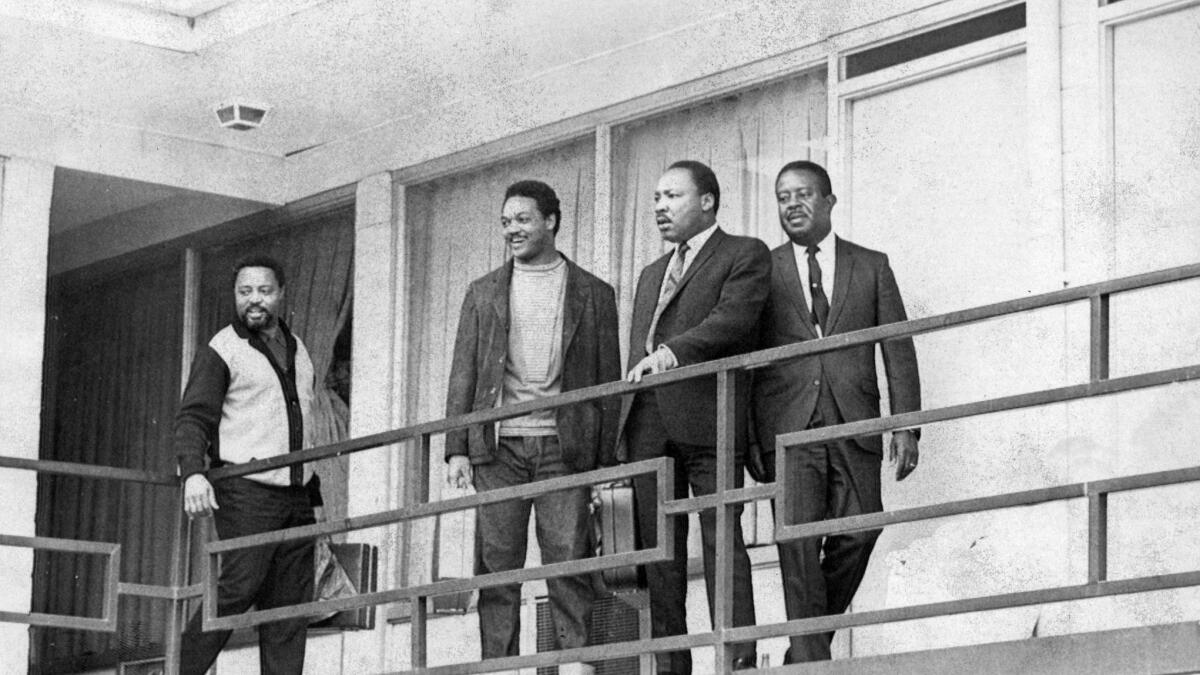

King was standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel and had turned to grab his coat. Moments later, he lay dying.

The sniper shot him from a building across the street. Jesse Jackson, the civil rights activist, saw the blood. Ralph Abernathy, the co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, ran to his side. By the time an ambulance had taken King from the motel to St. Joseph’s Hospital less than two miles away, King was dead.

News spreads

That evening, Abraham L. Davis was asleep in his Atlanta apartment when the sound of his neighbor’s television woke him up. It was a news report.

“I kept hearing Martin Luther King Jr. and his birthdate. As soon as I turned my TV on, it showed King’s picture, his birthdate and the day’s date,” said Davis, 79. “That day is deeply etched in my memory.”

“The next day was very solemn in Atlanta.”

Davis had trailed King at Morehouse College by 13 years. Though their paths didn’t cross as students at the historically black college in Atlanta, they would in the future.

Davis had met King during a protest orientation at an Atlanta church in the early 1960s and saw him again at the March on Washington in 1963.

Years later, he would make another, more personal, connection with the King family when he taught Martin Luther King III in his political science classes at Morehouse. “He took more courses under me than any other professor in his major,” Davis said. Another student had told Davis of King III’s presence, which was a surprise but also reflected family tradition: King’s father and brother also attended Morehouse.

“Martin Luther King III can you raise your hand?” Davis asked him in front of the entire class.

Xernona Clayton, a civil rights activist, had grown close to the King family through organizing events and marches for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. She learned of King's death while dining at an Atlanta restaurant when a waitress brought a note to her table. Clayton, not realizing the message was urgent, ignored it. Then the waitress returned.

"I hate to interrupt,” Clayton recalled her saying, “but I got the news that some harm had been done to King in Memphis.”

Clayton called the King home in Atlanta but the phone lines were busy. She drove to the house, arriving just as Coretta Scott King was leaving for the airport with Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen Jr., accompanied by a police escort. Coretta asked Clayton to stay with Coretta’s parents and children. King’s wife knew he had been shot but not his condition.

“When she got to the airport, she got the message that King had died,” Clayton said. Coretta chose not to fly to Memphis and went back to her children.

When she arrived, the King house on Sunset Avenue was surrounded by well-wishers, reporters and neighbors. “She was such a gracious lady,” Clayton recalled.

“She thanked everyone for their interest and concern."

Clayton, 88, was present when King’s widow received phone calls from President Lyndon B. Johnson and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy. She was there as Coretta tried speaking to her children about their father.

“Coretta did not tell the kids right away that he had died,” Clayton said. “Coretta told the kids King had been hurt. She couldn’t give them the truth just yet.”

Dexter, King’s second son, pleaded for more information about his father. “What will I tell my friends at school tomorrow?” he asked his mother.

Coretta told Dexter he wasn’t going to school the next day. “I think your teacher will understand,” she said.

Clayton also remembers witnessing a scene with Coretta and her first daughter Yolanda, then 13.

“Mommy, we’re not going to cry because we’re big girls and we can handle this,” Yolanda told her mother, sitting together on a bed. “I know you loved him and he loved you. The love will sustain us. We’re not gonna cry at all.” Despite the brave words, the mother and daughter wept.

On the opposite coast, Don Atwater had just placed an engagement ring on his fiance Libby’s finger. They had received a call from the jewelers that morning informing them that the gold ring was ready.

The couple had met at UCLA. As they drove to Atwater’s parents’ house to celebrate, they turned on the car radio. The sounds of chaos in Memphis and news of King’s death met them.

“Much of the joy I felt dissolved as I heard the terrible news,” Libby Atwater, 70, said.

Outrage grows

King’s death ignited widespread fury. Riots erupted, curfews were instated and National Guardsman were deployed. Fires raged in parts of Washington, D.C.

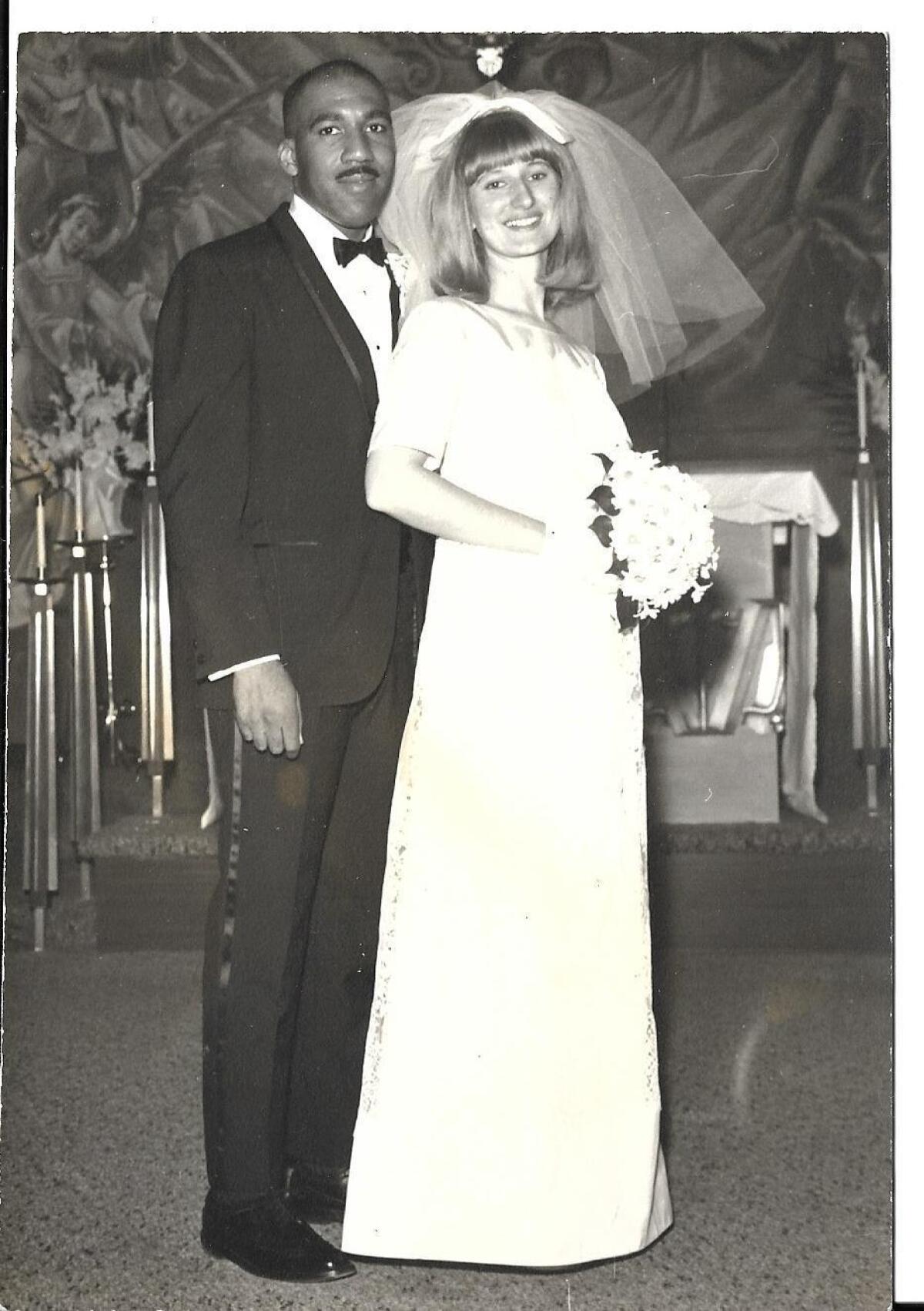

In Chicago, where King had led civil rights marches, a young couple feared for their safety.

Charles, a 28-year-old black man, and Janice, a 25-year-old white woman, were engaged to be married — less than a year after the Supreme Court struck down state laws that banned interracial marriages in Loving vs. Virginia.

The soon-to-be Tylers had already faced discrimination as an interracial couple. As the riots consumed their neighborhoods, a new worry consumed them.

Janice hid in the back of Charles’ car until they arrived at her apartment. They understood too well the racial division that King had tried to mend.

“When King was assassinated it was traumatic — like losing someone who was fighting for the same things,” Charles Tyler, 78, said. “It was a traumatic experience for everyone in the country.”

John Mackerer didn’t expect his first service to the United States to be inside the nation’s capital.

Mackerer, a 23-year-old West Point graduate, was stationed outside Washington with the 6th Armored Cavalry Regiment. As Washington burned, he was deployed.

“For the next days, we defended our capital from our own citizens.”

Two months later, he would be in Vietnam.

A nation mourns

King was laid to rest on April 9, 1968.

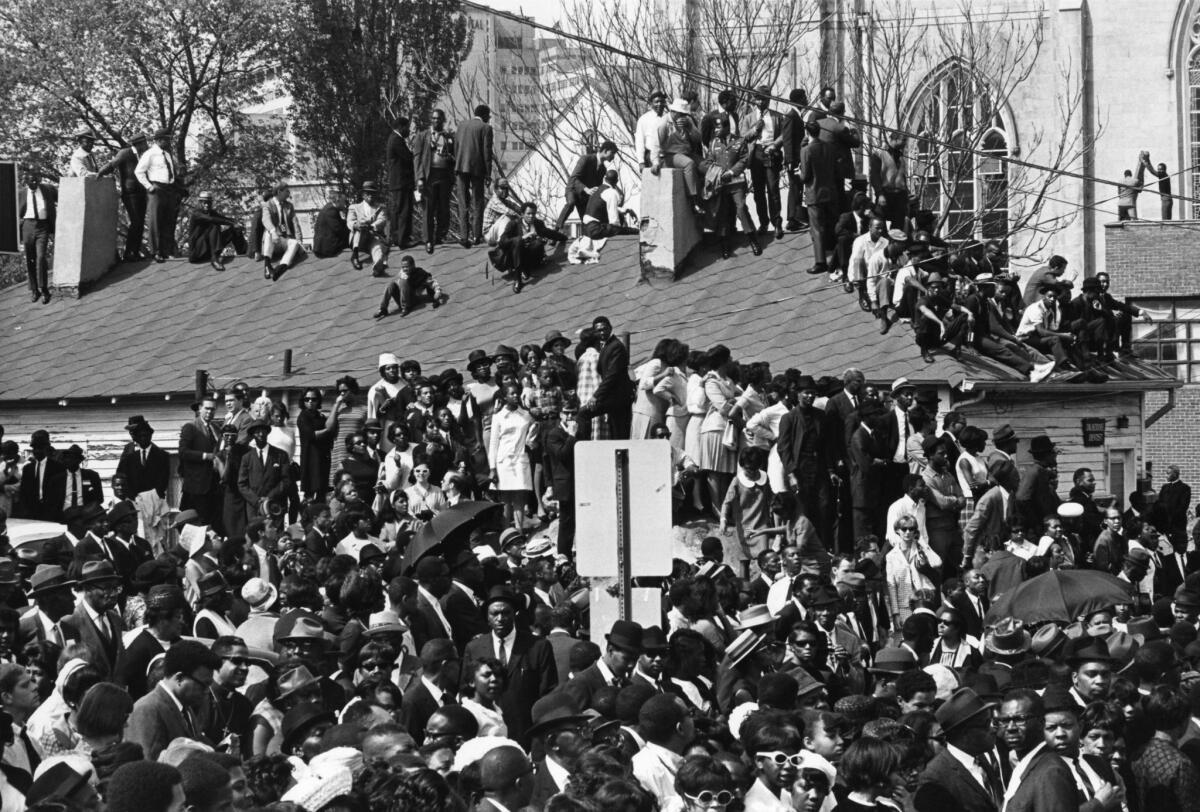

Thousands gathered outside the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, where a private ceremony was held for the civil rights leader.

Inside, several dignitaries joined King’s widow and children at the service.

Vice President Hubert Humphrey sat in the first row with Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. Jacqueline Kennedy, New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, Harry Belafonte and Sen. Edward M. Kennedy attended. As did three men running for president: Sen. Eugene McCarthy, former Vice President Richard Nixon and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, who would be killed just two months later.

Clayton was there as well. She remembers seeing King’s body at a family viewing the night before, and being appalled at the morticians’ treatment to his skin.

He “looked like someone grabbed a whole glob of red clay and slapped it across his face,” Clayton said.

“We all wanted him to look good, look natural and like himself,” she said. “I eased over to the mortician and asked if there was anything you can do to tone down that face. The mortician said, ‘The jaw was blown off! That’s the best I could do.’”

Growing desperate, Clayton mixed together face powder she borrowed from Coretta and Julie Robinson, then the wife of Harry Belafonte. She mixed the brown and white powder, creating something close to King’s complexion and applied it with a handkerchief. “I was trying to make that mark blend in to look more natural. And it worked,” Clayton said.

She would apply the mixture twice more: at midnight before he was taken to the church and the next morning before the private funeral.

During the service, a recording was played of one of King’s signature speeches, “The Drum Major Instinct.” During it, King imagines his own funeral. The speech had been delivered and recorded exactly one month before he was killed.

“Every now and then I think about my own death and I think about my own funeral. And I don’t think of it in a morbid sense. And every now and then I ask myself, ‘What is it that I would want said?’” King is heard saying.

“I’d like somebody to say that day that Martin Luther King Jr. tried to give his life serving others. I’d like for somebody to say that Martin Luther King Jr. tried to love somebody,” he answers.

King eventually is heard giving the often-quoted line: “Yes, if you want to say I was a drum major, say that I was a drum major for justice.”

Among those listening in the congregation were Lawrence G. Campbell and his wife, Gloria. The speech had King’s intended effect.

“It was not an atmosphere of death,” Campbell, 88, said of the funeral. “We felt more confident we would overcome the situations before us. It was a feeling for me and others to rejoice, not because of his death but what he died for.”

King had a profound influence on Campbell’s life.

“When I saw that King wanted to develop Christian leaders in the South, we joined him,” he said. “It gave me the courage and persistence to try to overcome racism.”

Campbell, the co-founder and bishop of Bibleway Cathedral in Danville, Va., remembered how King traveled to Danville in 1963 to show solidarity with protesters who were brutally beaten by police officers on what has become known as Bloody Monday. On June 10, 1963, about 40 protesters in Danville were arrested after marching to the municipal building to demand civil rights. Police went after them with billy clubs and fire hoses. Attendees of a prayer vigil later that day also were beaten by officers. More than 60 people were injured, including Gloria Campbell, who suffered a hip injury when hit with the high-powered spray from a fire hose.

King visited Danville the following month and called Bloody Monday one of the worst moments of police brutality he’d ever seen. After his visit to Danville, Campbell and local leaders took him to a Holiday Inn in Greensboro, N.C. That’s when Campbell saw a reminder of the perils King faced — a scar on his chest.

“He just chose to relax, and when he took off his shirt, we could see it,” Campbell said of the scar.

Seven years earlier, while attending a book signing in Harlem, King was attacked by Izola Curry, who stabbed him with a letter opener. Curry was later diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and lived in mental institutions until her death in March 2015.

King told Campbell that the letter opener was so deep in his chest, “If I had sneezed, I would’ve lost my life.”

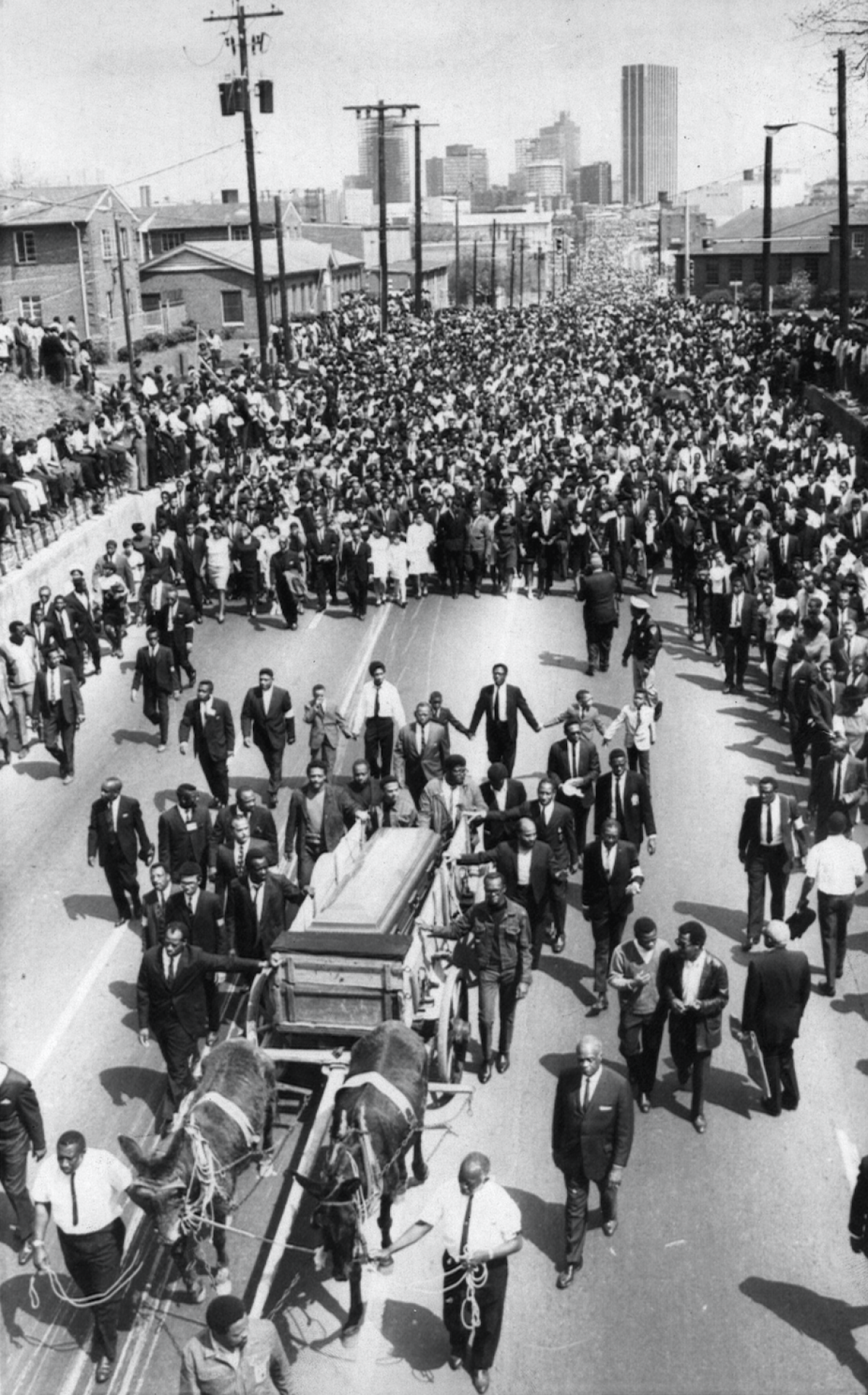

After the service, a simple wooden cart carrying King’s casket was pulled by two mules in a four-mile, two-hour procession to Morehouse College. At the gates, the crowd sang “We Shall Overcome.”

Davis remembers how younger mourners scrambled to view the procession.

“I could see these youngsters climbing the trees so they could get a good spot,” he said.

Davis could hardly move in the crowded campus chapel, where the congregation listened to spirituals and then-university President Benjamin Mays’ eulogy.

“When one woman got to the casket, she just stood there crying,” Davis said.

During Mays’ eulogy, he addressed the unrest that had caused millions of dollars in damage, prompted the arrests of thousands and left dozens dead. “If we love Martin Luther King Jr., and respect him, as this crowd surely testifies, let us see to it that he did not die in vain. Let us see to it that we do not dishonor his name by trying to solve our problems though rioting in the streets,” he said.

Mays acknowledged that the uprisings were a reaction to pain and loss. “Let us see to it also that the conditions that cause riots are promptly removed, as the president of the United States is trying to do.”

He ended his eulogy with a call to action: “Permit me to say that Martin Luther King Jr.’s unfinished work on earth must truly be our own.”

The spring of 1968 was bookended by death.

Mary Ann Solari came home from school to find her mother and neighbor watching a funeral on TV. The 7-year-old Bostonian was confused — hadn’t this program been shown before?

Her mother corrected her.

The first funeral was for King — a man who took on the title of “Dr.” not far from their home at Boston University.

This funeral was for a different man, her mother explained. His name was Kennedy, and he’d grown up just outside Boston.

“Two months separated their deaths, and to this day I remember that somber feeling,” Solari, 57, said.

1968 was a year that rarely gave leave to the disheartened.

Twitter: @cshalby

ALSO:

1968: A timeline of anger, grief and change

How 1968, a year of tumultuous events, continues to shape our world

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.