Seattle activist plans mobile drug haven to encourage safe use

Making drug use safer is the goal of the Seattle nonprofit People’s Harm Reduction Alliance.

Reporting from SEATTLE — In booming Seattle, where daydreams typically take the shape of mega-mansions and supersize yachts, street activist Shilo Murphy has managed to lower his expectations.

The techies at Amazon, Microsoft and other millionaire-minting factories can have their Lexuses and Lamborghinis. He’d be happy with a used van filled with heroin addicts, needles loaded and ready to fire.

Traveling neighborhood to neighborhood, with a nurse attendant aboard, the drug mobile would be the equivalent of a narcotics shooting gallery delivered to your doorstep. Let Jeff Bezos’ Amazon drones top that.

“It’s going to happen,” Murphy, 40, insisted, sitting at his desk in the basement of a church in Seattle’s University District, across the street from an entrance to the University of Washington. “We’re in the design stage. Maybe in a few months we’ll be rolling.”

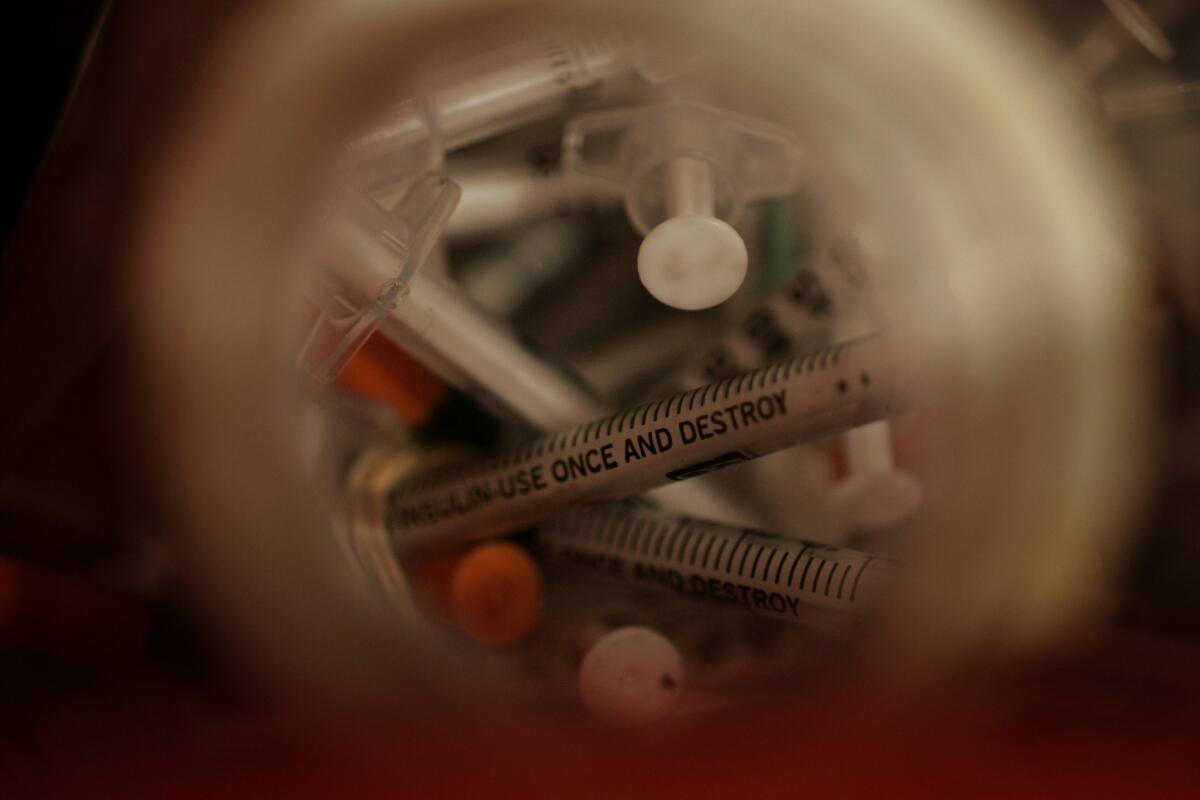

On cluttered shelves and in boxes stacked around him are some of the tools of his trade: new meth pipes, alcohol swabs and needles, needles, needles, all to be handed out free and, in some cases, against state law.

Including the maze of boxes stacked to the ceiling in a storage room nearby, Murphy has about 700,000 syringes. They’ll be gone in a few months, distributed by some of his 200 volunteers. By year’s end, the 25-year-old needle exchange program — largest in the U.S. — will have given out more than 4 million syringes to drug users, helping to protect them against HIV, hepatitis C and other needle-borne threats.

Making drug use safer has been the goal for the eight years Murphy has been executive director, and sole paid employee ($33,000 annually), of the nonprofit People’s Harm Reduction Alliance, dedicated to lowering the risks of drug addiction and controlling the spread of disease. The Seattle-born Murphy tried magic mushrooms at age 13 and eventually ended up with a heroin habit that put him on the streets and into a life of drugs.

Like the bundled figure asleep out on the church doorstep this morning, he came to the program 20 years ago for help, initially to exchange his own needles, then work as a volunteer. Murphy, a big, friendly man in a knit cabbie hat who likes to hug clients and tell them he loves them, remains an active if only occasional drug user — from tequila to heroin, he said.

Drug use by alliance staffers is not only allowed but also mandatory, Murphy said. “Under our bylaws, at least 51% of our employees, volunteers and board must be active drug users,” he said. It’s one of the few workplaces where failing the drug test boosts job security.

Inspired by Insite, a government-supported supervised drug facility in Vancouver, Canada, where addicts go to safely shoot up and obtain support services, Murphy and others planned to open a similar operation — the U.S.’ first safe, public injection site, but without government funding. Now they’re weighing the groundbreaking options of both stationary and mobile sites.

Both would be safe “consumption space” operations, allowing users of all kinds to inject, ingest or inhale the illegal substance of their choice as done at some European safe-use sites, Murphy said. To that end, his alliance is working with a loose coalition of local organizations and individuals, including the Seattle Public Defender Assn.

“A single facility,” said Patricia Sully, a staff attorney at the association, “would be a huge political victory and one we look forward to celebrating. But our goal is much bigger: We hope to bring not just a single safe consumption space to Seattle, but rather to make safe consumption spaces available city- and countywide.”

What do Seattle police think of drug-freedom zones, stationary or on wheels?

“Chief [Kathleen] O’Toole would need to hear more about the research before commenting on the efficacy of safe injection,” her spokesman, Sean Whitcomb, said.

King County Sheriff John Urquhart, however, is ready to give it a try.

“As long as there was strong, very strong, emphasis on education, services and recovery, I would say that yes, the benefits outweigh the drawbacks,” he said. “We will never make any headway in the war on drugs until we turn the war into a health issue.”

Seattle’s Democratic mayor, Ed Murray, and most City Council members are warm to the idea. Among the few to publicly express doubt is conservative KIRO-FM talk show host Jason Rantz, a Los Angeles transplant.

“Why would we normalize this kind of dangerous drug addiction? There’s no dispute in the medical community: Heroin is bad for you. So why normalize the behavior and supervise?” he said upon first hearing of the proposal a few months ago.

He hasn’t changed his mind, he said the other day. “I don’t know if I’d say this enables addiction, but it accommodates it rather than treats it,” he said. “We can call this compassionate, and I suppose it is, but what’s more compassionate and more meaningful is treating the addiction and the root causes.”

Sully said it had never made sense to use the criminal justice system to fix public health.

“If it were the case that without a safe consumption space, people would not use drugs, perhaps a better argument could be made against one,” she said in an email. “But with or without a safe place to do so, people who are chemically dependent on drugs will continue to use, and they will continue to do so in less ideal locations, namely, alleys and bathrooms.”

Besides mobile and stationary sites, the planning includes the possibility of using large, portable shipping containers as havens that can be moved to and from alternate locations. Murphy roughly estimates the startup and initial operation costs at $150,000, with private donors picking up much of the tab, and fundraising events and grants covering the rest.

“The money’s there,” he said. The alliance’s most recent tax filings, for 2013, show almost $183,000 received in contributions and grants that year; other years’ filings show donations twice that amount.

“We’re more Bernie Sanders than Donald Trump,” Murphy said of his donors. “We have a whole lot of $20 check writers.”

Many supporters are active or recovering addicts, a population that nationwide is growing in size and risk. A study by the Trust for America’s Health counted nearly 44,000 overdose deaths from drugs of all types nationwide in 2013, the most recent figures available. In King County, fatal heroin overdoses rose 58% in 2014.

More dramatic, the 314 deaths that year were triple the 99 deaths in 2012. Abetting the trend are the widespread use, abuse and overprescribing of prescription opiates, creating new consumers of widely available, and cheaper, heroin.

“Think of the benefits of a safe injection site,” Murphy said. “No needles on the ground, rapid response for those needing detox, connections to sources and services — and a nurse!”

He will hear from the NIMBYs and doubters regarding his plan, he said. But he added: “We’ve got to try something different. We’ve been here 25 years. It’s a success. We’ve saved untold lives. But if in 25 years it’s no different than it is today, then we’ve failed.”

Anderson is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.