Knocked sideways by Florence, New Bern rushes to get back on its feet

Reporting from New Bern, N.C. — All through the night as Hurricane Florence began hammering this city near the North Carolina coast, Paul Canady’s phone buzzed and beeped with messages from members of Christ Episcopal Church, where he serves as rector.

A collapsed tree leaned against a nearby house where a husband and wife live. A family huddled in their attic to escape the rising floodwaters. There was no electricity anywhere.

But by Saturday morning, the water was receding, the rain had abated and Canady’s flock appeared safe. So he drove downtown to see how the church itself had weathered the storm.

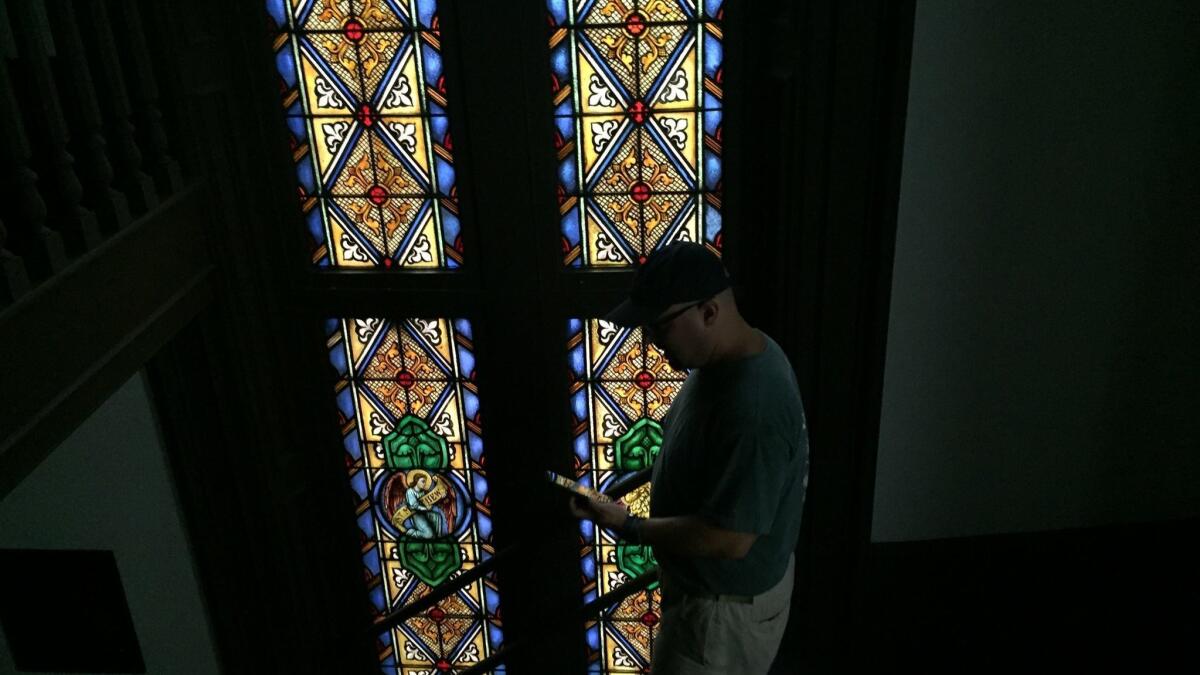

Besides the daylight shining through the stained-glass windows, the building was pitch black. Canady walked to the base of the bell tower, the highest point in New Bern, and climbed two metal ladders with a small flashlight. The wooden floorboards were damp, but everything appeared intact.

“We’re always grateful when the church can come through unscathed,” Canady said.

Across New Bern on Saturday, storm-weary residents were beginning to assess the damage from the worst hurricane in recent memory. Florence may have made landfall nearly 100 miles south, but this city of 30,000 was among the hardest hit in North Carolina.

Downtown businesses flooded, and hundreds of people needed to be rescued from their homes. Some neighborhoods remained underwater.

“I’ve seen a lot of hurricanes,” said Dana Outlaw, the city’s 64-year-old mayor. “And this is the big one.”

Founded in 1710, New Bern was once North Carolina’s largest city, prized for its location at the confluence of the Neuse and Trent rivers. Because the state lacked natural deepwater ports like its neighbors Virginia and South Carolina, ships from Europe would unload at nearby Portsmouth Island and transfer their goods to barges that would pass through New Bern on their journey inland.

But the location has also proved to be a vulnerability. During hurricanes, ocean water surges up the rivers and spills over the banks, inundating businesses and homes.

A pole on the site of the former colonial governor’s mansion, near where the two rivers meet, displays the high-water marks from previous storms. Florence will probably be one of the worst after delivering more than 10 feet of water, placing it nearly on par with Hurricane Ione from 1955.

“New Bern needs the prayers of all Americans,” Outlaw said. “It will take a team effort to restore our city.”

Although the storm has barely passed, that work has already begun.

Near the river, people were clearing out a seafood market and restaurant that had flooded. Wooden chairs, bags of hamburger buns, ketchup packets and scrap metal were piled on the sidewalk.

The owner, Ed McGovern, 61, had to swim through 6 feet of water to reach the store the previous day. Now he predicted it would reopen by Tuesday, maybe even Monday.

“I’ve got no choice,” he said. “I’ve got to stay busy. I’ve got to make money.”

There was a similar determination around the city as people seemed eager for some semblance of normalcy after being hunkered down the previous two nights.

Gas stations were reopening for business. A line of cars at the Smithfield’s Chicken ‘N Bar-B-Q drive-through snaked around the restaurant, out of the parking lot, down the street and up the highway offramp, causing a culinary traffic jam.

Al Sibley, 85, had waited for an hour in his vehicle, along with his wife and their small yapping dog, for a pound of barbecue, a pound of coleslaw and an order of hush puppies.

“This is the first time we’ve been out of the house,” he said.

One of the city’s Piggly Wiggly grocery stores lost its facade in the storm, the metal crumpled like discarded wrapping paper in front of the building.

But Danny Creel, 52, the store’s manager, seemed relieved. The roof was intact and the store had barely lost power, meaning the perishables were mostly safe. Workers were on the way to haul away the metal, and he planned to reopen the next day.

“I’m already smiling,” Creel said. “It could have been a lot worse.”

A few blocks from the store, closer to the Neuse River, some people were still being rescued from flooded houses.

Jerry and Denise Railling had spent the entire storm in their home, refusing to heed evacuation orders even when the water rose to their knees. They huddled on their bed with their dog, Snookie, and their cat, Booboo Kitty.

“The box spring was wet, but the mattress was dry,” Jerry, 72, said.

But on Saturday, volunteers from as far away as Texas and California reached the home by personal watercraft to warn that there was probably sewage in the water. It wasn’t safe to stay.

Jerry, Denise and Booboo Kitty came out first. Then one volunteer returned to fetch Snookie, who was placed in a life jacket for the ride.

Over the previous two days, the city was the site of some of the most intense emergency work in the state, and Outlaw said roughly 400 people had been rescued from the flooding. Some were plucked off their rooftops with boats. Others waded through floodwaters to giant National Guard trucks.

A fire station near downtown had been a hub of activity, with out-of-state crews and local teams cycling in and out to answer distress calls. Rescue workers napped in darkened rooms between shifts, and firefighters grilled ribs over a large barbecue to fuel the long days.

Darren Sumner, 50, evacuated his home with his wife and his daughter during the storm, but the shelter at a nearby school wouldn’t take dogs, so he left behind Lightning, the family’s 160-pound Alasakan malamute.

Lightning was safe when Sumner finally returned home, and on Saturday morning he took the dog for his first walk since the evacuation.

“He’s his nice, friendly self,” Sumner said. “He’s probably a little mad at me, though.”

On the outskirts of town, Chuck Warren, 56, a heating and air conditioning technician, stood outside his home in his bathrobe. The storm had stripped shingles off his roof, and rain started leaking in.

“I fought it with buckets as long as I could,” he said. “Until the ceiling collapsed.”

After that, he got on top of his house with plastic sheets, which he pinned to the roof with plywood as the wind threatened to blow him off.

Warren can count himself lucky. A tree toppled onto his neighbors’ roof, splitting it like an ax. Several years ago Warren had pulled nearly three dozen trees from his front and back yards, fearing something exactly like that could happen to him.

He thinks the worst is over for New Bern, but he pointed at a fractured branch dangling precariously above a power line leading to his house.

“There are still issues to come,” he said.

Twitter: @chrismegerian

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.