Tropical Storm Harvey, which destroyed thousands of homes and businesses across southeastern Texas, is now estimated to be one of the costliest disasters in American history, with damages that could exceed $100 billion.

Rebuilding efforts along the Gulf Coast, already expected to take years, will be complicated by the fact that fewer than one in five homeowners in the Houston area are insured against flood damage. Those without it could wait months, or years, to fund costly renovations themselves or receive government relief funds.

Even people with insurance are not in the clear as they will be dealing with a program that is mired in problems: The National Flood Insurance Program is nearly $25 billion in debt and will expire Sept. 30 if Congress does not extend it.

Lawmakers and experts are debating how to improve the program’s long-term financial outlook, which could include requiring more homeowners to buy flood insurance or discouraging people from rebuilding in areas that will see more storms.

Texas is “one of the biggest recipients of relief money, but flood insurance has done very poorly in Texas,“ said Scott Knowles, a disaster historian at Drexel University.

After decades of relatively stability, the flood insurance program fell into debt after paying out nearly $25 billion in claims from Katrina and Superstorm Sandy, which could not be covered through policyholders’ premiums. Today the program has $5.8 billion in borrowing authority from the U.S. Treasury.

Payments from Harvey are expected to far exceed that limit.

1/87

Samir Novruzov wades through water to get to a vehicle after spending the day clearing out his flooded home in Katy, Texas.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 2/87

Melissa Teague, right, instructs her children Andrew and Emily as they clear out their flooded home in Katy, Texas, on Monday.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 3/87

People ride through floodwaters in Katy, Texas.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 4/87

People hop off Chris Ginter’s truck as he helps ferry residents around Katy, Texas.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 5/87

Two men collect a disposed mattress as residents in the Trinity/Houston Garden area of northeast Houston gut their flooded homes.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 6/87

Wayne Christopher, center, weeps as his wife, Helen, looks on during a Sunday service at First United Methodist Church in Dickinson, Texas.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 7/87

Hurricane Harvey severely damaged the First Baptist Church in Rockport, Texas. Worshipers on Sunday brought their own chairs to take part in an outdoor service.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 8/87

Ken Garrett, right, hugs Pastor Jordan Mims after they both delivered prayers on the grounds of the First Baptist Church in Rockport, Texas.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 9/87

University of Houston law professor Johnny Buckles props up an American flag on the debris pile from his flood-damaged home in the Kingwood area of north Houston.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 10/87

Jose Esquivel flags down motorists to visit a parking lot full of donated clothes, supples, water and brisket in Refugio, Texas.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 11/87

Despite heavy damage and no electricity, a homeowner displays his patriotism while clean up and recovery efforts continue in his devastated neighborhood of Rockport.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 12/87

Volunteers from the Ahmadiyya Muslim Youth Association, Yusuf Seager, from left, Rahib Ahmed, Rahman Nasir, and Khalil Nasir help tear out drywall damaged by floodwater in the Westbury neighborhood in Houston.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 13/87

Volunteers from the Ahmadiyya Muslim Youth Association help residents of the Westbury neighborhood in Houston clear debris from their homes. It is also the Islamic holiday of Eid-ul-Adha. (Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times)

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 14/87

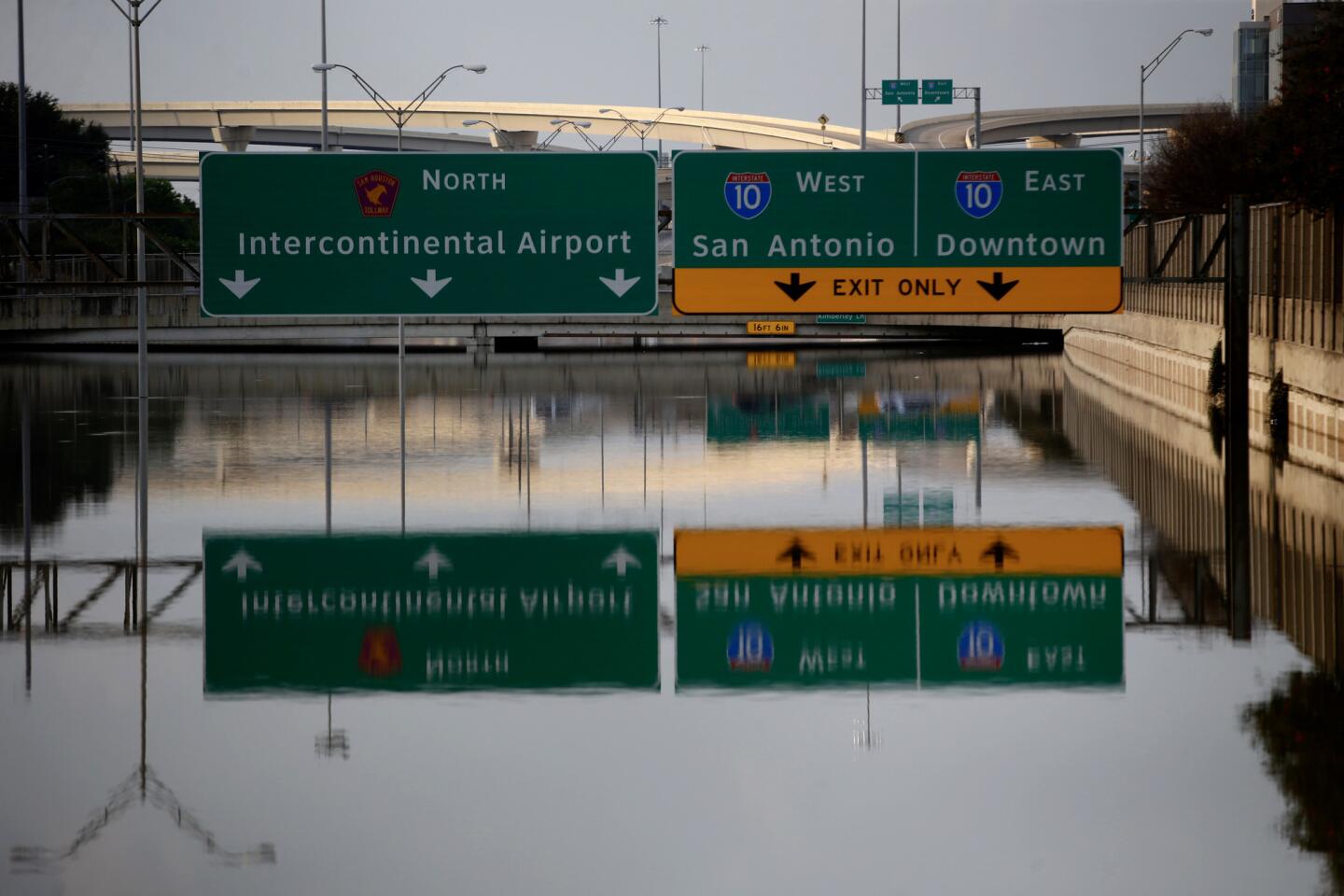

Many roads and Interstates in Texas remain flooded, including this one in west Houston. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

15/87

Jenna Fountain and her father Kevin carry a bucket down Regency Drive to try to recover items from their flooded home in Port Arthur, Texas on Thursday.

(Emily Kask / AFP / Getty Images) 16/87

Lillie Roberts talks with family members as contractor Jerry Garza begins the process of repairing her Houston home on Friday.

(Scott Olson / Getty Images) 17/87

Volunteers from the Ahmadiyya Muslim Youth Association to perform holy prayer as they help local residents in the Kashmere Gardens area of Houston clean out their flooded homes.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 18/87

Volunteers assist Cornell Beasley with repairs to his damaged home in Houston on Friday.

(Scott Olson / Getty Images) 19/87

Katie Estridge organizes hundreds of soaked family photographs on the front lawn of her father’s home in northeast Houston.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 20/87

Wes Higgins wipes sweat from his face after spending five days patrolling flooded Houston neighborhoods in his boat. Higgins, from Knott, Texas, organized a volunteer team of 10 boats to help Houston residents.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 21/87

Members of the California Air National Guard 129th Rescue Wing, Senior Airman George McKenzie, left, and Master Sgt. Adam Vanhaaster, right, help a man carry his infant, who has a serious medical condition, to a hospital in Orange, Texas.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 22/87

A search-and-rescue crew speeds along Maple Rock Drive in west Houston looking for flood victims.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 23/87

A woman and a child are among those rescued by California Air National Guardsmen in Lumberton, north of Beaumont.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 24/87

California Air National Guard 129th Rescue Wing’s Master Sgt. Adam Vanhaaster searches for people in need of help near Lumberton.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 25/87

A man prepares his dinner at home near Lumberton.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 26/87

Boys sit on a damaged railroad track near Lumberton.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 27/87

A woman waves to a California Air National Guard helicopter from her neighborhood near Lumberton.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 28/87

A drop-off point for boat rescues in Lumberton.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 29/87

Baseball fields in Lumberton are inundated.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 30/87

Coca-Cola delivery trucks are trapped by floodwater in Lumberton, Texas.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 31/87

A military search and rescue helicopter refuels mid-flight before resuming nighttime missions over areas flooded in the aftermath of Tropical Storm Harvey.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 32/87

Houston police search a flooded home after hearing that an elderly couple lived there. The house was empty. Police later learned the couple had safely evacuated.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 33/87

West Houston resident Pedro Albiso uses trash bags to protect his shoes and pants as he prepares to cross a flooded street.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 34/87

Patients are evacuated from Baptist Hospitals of Southeast Texas after the city of Beaumont lost its water supply.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 35/87

Fatima Flores, 12, gets her hair done by cousins Shelly Flores, 7, left, and Ashley Flores, 7, as their family takes shelter at Max Bowl, a bowling alley in Port Arthur, Texas.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 36/87

James Benoit, left, and George Clipton sought refuge at Max Bowl in Port Arthur, Texas.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 37/87

June Ayrow spent the night with his oxygen tanks underneath a table at Max Bowl in Port Arthur, Texas.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 38/87

Floodwaters surround homes Thursday in Port Arthur, Texas.

(Gerald Herbert / Associated Press) 39/87

Volunteers rescue patients from the Cypress Glen nursing home where floodwaters trapped dozens of elderly patients in Port Arthur, Texas on Wednesday.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 40/87

Residents lie on sofas as they wait to be evacuated from the Cypress Glen senior care facility in Port Arthur, Texas, which was inundated with floodwaters from Tropical Storm Harvey on Wednesday.

(Matt Pearce / Los Angeles Times) 41/87

Emergency crews help rescue elderly residents from the Golden Years Assisted Living home in Orange, Texas, on Wednesday.

(Gerald Herbert / Associated Press) 42/87

Rescuer workers help a woman from her flooded home n Port Arthur, Texas.

(Joe Raedle / Getty Images) 43/87

Evacuees ride on a truck after they were driven from their homes by the flooding in Port Arthur, Texas.

(Joe Raedle / Getty Images) 44/87

People wait in line to buy groceries at a Food Town during the aftermath of Tropical Storm Harvey.

(Brendan Smialowski / AFP/Getty Images) 45/87

Juan Figueroa removes damaged furniture from his mother’s northeast Houston home where residents begin rebuilding from the devastating effects of the storm.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 46/87

Rafael Minor, left, and Miguel Ramirez remove the contents from a flooded home in northeast Houston on Wednesday.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 47/87

A construction crew cleans out a home that was flooded by Tropical Storm Harvey in Spring, Texas.

(Brett Coomer / Associated Press) 48/87

A flooded residential neighborhood near Interstate 10 in Houston, Texas.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 49/87

A flooded residential neighborhood near Interstate 10 in Houston, Texas.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 50/87

People come out to view the flooded areas near their homes in Houston, Texas.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 51/87

CaroLine Kirkpatrick of Salt Lake City, Utah, is evacuated from the Omni Hotel by rescue worker Adam Caballero in Addicks, a suburb of Houston, Texas.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 52/87

People displaced by flooding fill the shelter at the George R. Brown Convention Center in downtown Houston.

(LM Otero / Associated Press) 53/87

Mark Ocosta and his baby, Aubrey, take shelter at the George R. Brown Convention Center.

(Joe Raedle / Getty Images) 54/87

Frantzy Thenor receives an embrace from a fellow evacuee after he helped her leave from the flooded Omni Hotel, in the Addicks area of Houston, Texas.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 55/87

Storm clouds over Houston skyline.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 56/87

Recreational vehicles sit on their sides in flood water in Houston, Texas.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 57/87

A woman carries a dog above the rising floodwaters near Addicks Reservoir.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 58/87

Eduardo Retiz, 21, drives his elevated pickup truck through a flooded street near Addicks Reservoir.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 59/87

Mike Hoskovec, left, walks to a boat after helping friend Ben Berg, behind, move some photo albums to the second floor of his Nottingham Woods home.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 60/87

Matthew Koser looks for important papers and heirlooms inside his grandfather’s house after it was flooded by heavy rains.

(Erich Schlegel / Getty Images) 61/87

Residents wade through floodwaters as they evacuate their homes near the Addicks Reservoir Tuesday.

(David J. Phillip / Associated Press) 62/87

Larry Koser Jr., left and his son Matthew look for important papers and heirlooms inside Larry Koser Sr.’s house after it was flooded by heavy rains.

(Erich Schlegel / Getty Images) 63/87

Portions of Interstate 10 remain flooded in Houston, Texas.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 64/87

Rising flood waters stranded hundreds of residents of Twin Oaks Village in Clodine.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 65/87

Comfort Morgan is helped to dry land after being rescued from her flooded home in Twin Oaks Village in Clodine.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 66/87

Rising flood waters stranded hundreds of residents of Twin Oaks Village in Clodine, where a collection of small boat owners, including some with pool toys, coordinated to bring most to dry ground.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 67/87

Rising flood waters stranded hundreds of residents of Twin Oaks Village in Clodine, where an collection of small boat owners coordinated to bring most to dry ground.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 68/87

Hundreds of residents of Twin Oaks Village are evacuated in Clodine Monday.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 69/87

Residents are stranded at Twin Oaks Village in Clodine due to rising flood water.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 70/87

Stranded residents of Twin Oaks Village in Clodine are evacuated from the rising flood water.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 71/87

Jan Tullos, 32, searches a flooded home for an injured woman who was reportedly stranded inside in Clodine, Texas. The home was empty.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 72/87

People walk down a flooded Houston street as they evacuate their homes after the area was inundated with rains from Tropical Storm Harvey.

(Joe Raedle / Getty Images) 73/87

Dean Mize holds children as he and Jason Legnon use an airboat to rescue people from flooded homes in Houston on Monday.

(Joe Raedle / Getty Images) 74/87

Dean Mize, left and Jason Legnon carry a person to an airboat as they rescue people in Houston.

(Joe Raedle / Getty Images) 75/87

Evacuees walk down a flooded street after leaaving their homes Monday in Houston.

(Joe Raedle / Getty Images) 76/87

Dean Mize holds a child as he helps evacuate people in Houston as Tropical Storm Harvey continues to drench southeastern Texas and Louisiana with heavy rains and surging floodwaters.

(Joe Raedle / Getty Images) 77/87

People evacuate their flooded homes on Monday in Houston. By Monday morning, 911 operators had received 56,000 calls, city officials said.

(Joe Raedle / Getty Images) 78/87

Adults use a kiddie pool to transport children as they evacuate on Monday.

(Joe Raedle / Getty Images) 79/87

People catch a ride on a construction vehicle down a flooded Houston street.

(Joe Raedle / Getty Images) 80/87

Alexendre Jorge evacuates Ethan Colman, 4, from a Houston neighborhood inundated by floodwaters from Tropical Storm Harvey.

(Charlie Riedel / AP) 81/87

People push a stalled pickup to through a flooded street in Houston on Sunday, as Tropical Storm Harvey dumped heavy rains.

(Charlie Riedel / Associated Press) 82/87

A Houston police officer helps Frank Andrews, 74, into his walking chair after rescuing him from his flooded home in the Braeswood Place neighborhood, southwest of Houston, on Sunday.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 83/87

Wilford Martinez, right, is rescued from his flooded car by Harris County Sheriff’s Department Richard Wagner along Interstate 610 in Houston, Texas.

(David J. Phillip / Associated Press) 84/87

Daniel Gross, 15, is rescued by Houston police after he was stranded on top of his car in southwest Houston.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 85/87

Andrew White, left, helps a neighbor down a street after rescuing her from her home in his boat in the upscale River Oaks neighborhood after it was inundated with flooding from Tropical Storm Harvey.

(Scott Olson / Getty Images) 86/87

Volunteers and officers from the neighborhood security patrol help rescue residents in Houston’s River Oaks neighborhood Sunday.

(Scott Olson / Getty Images) 87/87

Jesus Nunez carries his daughter Genesis, 6, as he and numerous family members flee their flooded home, walking nearly four hours to the safety of a relative’s house on Sunday.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) Harvey swept through a swath of southeast Texas, triggering disaster declarations in 19 counties.

The national forecasting firm Moody’s Analytics estimated total damages of between $81 billion and $108 billion, which would make Harvey the second costliest storm in U.S. history, behind Katrina, which cost $175 billion.

An estimated 400,000 homes and 700,000 vehicles were significantly damaged. More than 32,000 people have been housed in shelters.

The effects will be felt more broadly as they sap momentum from the U.S. economy. Motorists across the country can expect to pay more for gas, at least for a while, and consumer spending overall could fall a bit as well. U.S. exports could see a slight drop from the temporary closure of one of the nation’s busiest ports.

Already, more than 51,000 people have filed claims with the national flood insurance program, a number that will certainly rise. Each policyholder can receive up to $250,000 for repairs to their homes, and up to $100,00 for what’s inside.

That gets to the heart of the problem with the flood insurance program, experts say: Because subsidies have kept premiums artificially low, it can’t pay for itself, particularly as the number of severe storms gets worse.

“Carrying around a deficit that they’re never going to repay doesn’t make any sense,” said Carolyn Kousky, the director of policy research at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton Risk Management Center.

Congress created the National Flood Insurance Program in 1968, three years after Hurricane Betsy devastated parts of Florida and the central Gulf Coast.

Few private firms had offered flood insurance, because costly, simultaneous payouts seen during disasters could easily bankrupt a company. The new federal program aimed to provide some financial stability for homeowners in flood plains.

The program is administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency and today insures about 5 million Americans.

Homeowners in identified flood-risk zones are required to buy insurance through private companies, but the federal government establishes the rates and provides subsidies to keep them down.

FEMA’s maps require policies in areas with a 1 in 100 chance of severe flooding in any a given year. But many people whose homes are not in those areas still face the risk of flooding.

Maps are frequently outdated — the map of New Orleans had not been updated for two decades when Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005 — and don’t factor in the flooding risk from rainfall during storms, which scientists say will happen more regularly in the future.

“The risk of flooding is changing across the entire landscape of the country, and that’s not communicated well to homeowners,” Kousky said. “You get people who are outside the line who think think they’re safe. It doesn’t mean that all.”

In the Houston area, the high-risk zones cover a fraction of the city, typically along the rivers and bayous. The number of policies has dropped over the last five years.

The average annual premium in Houston is $555.

The cheap rates have also confused some homeowners about the risk of flooding in their neighborhood.

“If you had to pay the full cost of a risk, then that might discourage people from living in really risky areas, or building in ways that are risky,” Kousky said. “There are areas, where, frankly, we shouldn’t be building.”

Congress also allowed homeowners to keep older, lower rates, if analysts later find their homes are at greater risk of floods. Critics say that grandfather clause has spiraled into a federal subsidy for risky building on flood plains. Today, up to a fifth of policy holders pay premiums that are artificially low, officials say..

Local areas interested in providing flood insurance for residents are required to craft zoning policies designed to discourage building in flood plains — a rule that Kousky said is essentially unenforceable in Texas because of its size.

In Houston, decades of dramatic growth in the suburbs has crippled the region’s natural drainage system of freshwater wetlands. Water-resistant surfaces such as concrete rose by one-fourth over a 15-year period that ended in 2011, a Texas A&M University study found.

Researchers concluded that the type of development also mattered: Houston’s low-density sprawl increased losses from flood damage, while denser development decreased it.

“A state with very, very lax building codes has managed to access this program and has continued to build in ways that put people at risk,” said Rebecca Elliott, a London School of Economics assistant professor who is working on a book about how the U.S. handles the cost of major floods.

About 1% of the highest-risk homes have received about 30% of funds from the program. More than 30,000 homes across the U.S. are classified as “severe repetitive loss” homes — properties that have been rebuilt with government funds an average of five times.

In Harris County, FEMA has spent $265 million on claims for 1,155 of those homes, according to data from the National Resources Defense Council.

Citing many of these factors, government auditors have classified the program as “high risk,” noting that claims administrators don’t have the information they need to make sound payouts. One way to make the program more sound, auditors said, would be to spend more money on mitigation.

Lawmakers across the political spectrum would like to see similar reforms, but progress has been sporadic .

In 2012, Congress passed a bill aimed at shoring up the flood insurance program’s financial future, only to rescind the changes two years later after homeowners complained that their premiums had soared.

Two years ago, President Obama signed a directive requiring federally funded projects to meet a series of flood-risk standards. That policy was reversed two weeks ago, as part of President Trump’s push to roll back environmental rules to speed infrastructure projects.

“This was an opportunity to do something we see very rarely on the Hill, which is to satisfy fiscal hawks and environmental concerns,” said Knowles of Drexel University. “Congress did something good, then they undid it. Now, they have an opportunity to do something again.”

In Washington, legislators are wrangling over whether to address the issues now, or extend the program without making any changes.

Tom Bossert, homeland security advisor for President Trump, said the administration would like lawmakers to extend the program as is, then debate policy changes later this fall. At least $8.6 billion is available to cover claims from Harvey, he said.

“I don’t think now is the time to debate those things, as we need to help people that have pending claims,” Bossert said at a White House press briefing Thursday.

A package of bills advocating for higher premiums and more involvement by the private insurance market is awaiting a U.S. House vote, but more than 100 members have already said they will not sign it.

[email protected]

Twitter: @laura_nelson

[email protected]

Twitter: @dleelatimes

Times staff writer Lauren Rosenblatt contributed to this report.

ALSO

Muslim volunteers spend Eid helping Houston hurricane recovery

For Texas immigrants, Harvey came at an already tense time

As Harvey moves east, a ‘Cajun Navy’ of volunteers descends on Port Arthur to rescue people