Latest pastime in an Arizona hippie enclave: Speculating about why Warren Buffett’s son is in town

Reporting from Bisbee, Ariz. — “Electric” Dave Banham slugged back the last of his beer, wiped his lips and resumed his barstool rant about the new rich guy in town.

“What’s he up to? What are those towers? Who is he driving around with?” Banham asked the bartender at the Double P Roadhouse and a couple of whiskery locals nursing cocktails. “What the hell is Warren Buffett’s kid doing down here?”

Ever since Howard Graham Buffett arrived in this hippie enclave in 2013, speculating about his motives has become a local pastime. That he’s rarely seen in public has deepened the mystery.

Each report of a new contribution to the Cochise County Sheriff’s Office — the $1.2-million helicopter, the $4-million encrypted radio network, the new cruisers and drug-sniffing dogs — has unleashed a new round of intrigue.

Compared to the rumors, the truth isn’t very exciting: Buffett is just being Buffett.

Someday he will become the next non-executive chairman of his famous father’s empire, Berkshire Hathaway. At least that’s the family plan. In the meantime, he has focused on running the Howard G. Buffett Foundation, which focuses on improving food security in Africa.

Seeking a North American research farm that mimicked a sub-Saharan climate and landscape, he settled on southern Arizona and bought a 1,400-acre farm to test various growing techniques. He lives for about four months a year on another ranch he bought in the Mule Mountains along the Mexican border.

The foundation, which is based in Decatur, Ill., and spends about $150 million a year on projects, mostly in the developing world, also conducts research on land that Buffett owns in Illinois in Decatur and Macon counties.

In all three places, 61-year-old Buffett has used the foundation to indulge another of his interests: policing.

In Cochise County, where he has donated the most, he gave the sheriff’s office $6 million in 2014 — the most recent year for which records were available — a sizable addition to the $15 million it receives from the county.

That spending has made Buffett a hero to local law enforcement — and a focus of conjecture among conspiracy-minded folk.

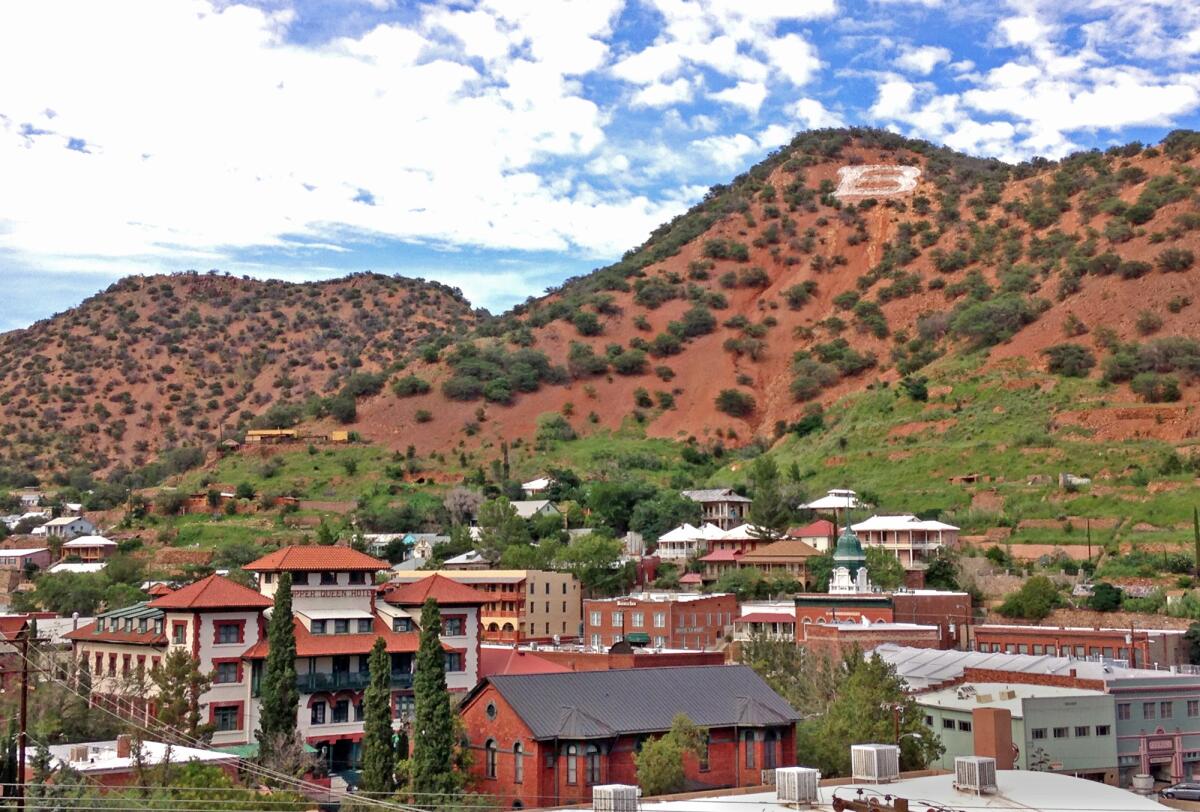

Bisbee’s unofficial motto is: “The World’s Largest Open-Air Insane Asylum.”

For most of its history, the town produced astounding quantities of copper from massive pit mining operations. But the mines died out in the 1970s and the miners moved out.

With the town on the brink of extinction, artists and hippies started moving in. Seeking clean mountain air and cheap living, they found both in Bisbee and transformed the town into one of the few liberal strongholds in Arizona.

It was the first city in the state to approve of civil unions and among the first to have a medical marijuana dispensary.

The people who live here are suspicious of law enforcement, the county government and — owing to the piles of mining waste that surround the town — even their own soil and water.

Nothing related to Buffett has generated as much speculation as what have become known simply as “the towers.”

Shortly after he arrived, 30-foot-tall radio towers sprang up on the hillsides outside Bisbee, including several near the border, surrounded by fencing and warning signs. The towers were part of the radio system he donated.

But nobody explained that to Alison McLeod, who lives in Bisbee and reports on the presence of law enforcement in the area on her own YouTube channel.

When the towers went up, McLeod started driving around to make videos of them. At one point, she used the driveway of Buffett’s ranch in Willcox to turn around.

The next day, McLeod said, the sheriff, Mark Dannels, and his chief deputy, Mark Gentz, came to her house warning her not to trespass on Buffett’s property.

“Here is the No. 1 law enforcement official in the whole county and he’s at my door?” McLeod said. “What kind of a show of force is that? Who has [Buffett] got in his pocket, and what is he going to do with them?”

Ann Kelly Bolten, the president of Buffett’s foundation, said most of what McLeod has filmed is government infrastructure.

“This individual — like the vast majority of people who could be described as our neighbors — is unaware of the hundreds of millions of dollars we spend on humanitarian efforts,” Bolten said in an email. “I’m sure if you talk to her she will have very strong opinions about Howard but they won’t have anything to do with what we are actually doing in Arizona.

“The grants are the story, period,” she wrote.

The story of how Buffett got interested in feeding the developing world started with an interest in agriculture as a boy growing up in Omaha and continued with his extensive international travels.

His interest in agriculture brought him to rural counties, where he bought farms and got to know the local cops. So began a fascination with law enforcement.

“[Life] experience made me realize how easy it is to take rule of law for granted when you have it,” Buffett wrote in response to written questions from The Times, “and how devastating it can be to a society when rule of law is corrupted or missing altogether.”

His involvement in policing goes beyond funding it to actually doing it.

Through training available to any citizen, he has earned his certification to operate as a volunteer deputy in counties in Illinois and Arizona, putting in more than 500 patrol hours since 2013. Additional training included dealing with hostage-takers and leading drug-sniffing dogs.

On patrol, he has participated in stops and arrests alongside a senior officer, but he has never used his gun, he said.

In Arizona, Buffett was granted the title of “deputy commander” and made a uniformed liaison to the ranching community.

“Howard isn’t just looking in, he’s fully here,” the sheriff said in an interview. “He’s committed, and we need more people to do what he does.”

See the most-read stories this hour »

While Buffett’s involvement has endeared him to law enforcement officials, it has also caused him to worry that he could become a target for drug smugglers who haul their product from Mexico into Arizona. Suspected traffickers followed him home one day and noted his license plate number, he wrote to Dannels.

“We just need to keep the connection low right now,” he wrote.

Back at the Double P Roadhouse, Electric Dave Banham wasn’t letting up.

A grey-haired, portly man several stools down was getting annoyed. He turned his head from the bar’s lone television, scowled at Banham, then stood up and left.

“What’s his problem?” Banham asked the bartender, who shrugged.

His problem, Banham said he later learned, was that he was Howard Buffett.

Twitter: @nigelduara

Times researcher Scott J. Wilson contributed to this story.

ALSO

Old and poor: An especially bad combination in this Arizona county

It’s summer in Arizona: Time to come inside

Hours-long lines, goofs with ballot materials. Why can’t Arizona hold elections?

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.