Q&A: Could Russian hackers mess with the U.S. election results? It wouldn’t be easy

Reporting from Washington — The recent Russian hack into the Democratic National Committee’s computers and subsequent FBI warning that two states’ elections databases had been victims of cyberattacks are raising fears that a foreign power might penetrate U.S. systems and try to alter the outcome of November’s vote.

Though possible, such an unprecedented foreign election-day hacking would be hard to pull off, experts say. Here are some answers to common questions:

How realistic is the threat that hackers could break into U.S. election systems and alter vote tallies?

Not very, thanks mostly to the fact that even presidential elections are highly decentralized and often still rely on old-fashioned systems rather than cutting-edge technology.

First, there are more than 8,000 separate local jurisdictions where voters cast ballots for president, and each one is largely free to use whatever methods, technology and vendors they deem appropriate, based on varying local or state rules and guidelines. There are few federal mandates on how to conduct elections, and the mechanics of voting have been left to the states. For would-be hackers, that means there’s no easy, one-stop target.

Secondly, about 75% of all votes this cycle will be cast on paper, said Pamela Smith, president of Verified Voting, which tracks election systems nationwide And many results are still conveyed by telephone, fax or hand delivery.

Even in cases where results are tallied or transferred electronically, if someone were to try to surreptitiously alter official results, there are built-in redundancies — such as following up an email with a phone call, fax or hand delivery. And with paper, a hand recount is always possible whenever in doubt.

Very few voting machines are directly connected to the Internet, where they might be targeted by hackers based in foreign countries, said Denise Merrill, secretary of state of Connecticut and president of the National Assn. of Secretaries of State.

For hackers to infiltrate voting machines not connected to the Internet, they would need to individually install a bug or virus, presumably by hand, and then hope that one machine spreads the virus to another, or to a computer that tabulates the results. It’s possible, and experts note that most voting machines are usually left unguarded on election eve in schools, town halls and other polling places. But it’s not likely, particularly on a scale that would make a difference.

“I think it is highly improbable that anything that has been suggested could happen,” Merrill said. “There are thousands upon thousands of polling places, each operated independently, by nonpartisan people. It is all broken into such small units, it is just hard to imagine someone hacking into them and being able to make much of a difference in the outcome.”

James B. Comey, the FBI director, reiterated that view during a security forum in Washington on Thursday, saying that the U.S. election system’s antiquated nature is beneficial from a security standpoint.

“The voting system is dispersed among 50 states. It’s clunky as heck,” Comey said.

Didn’t many jurisdictions move to computerized voting after the disputed 2000 election?

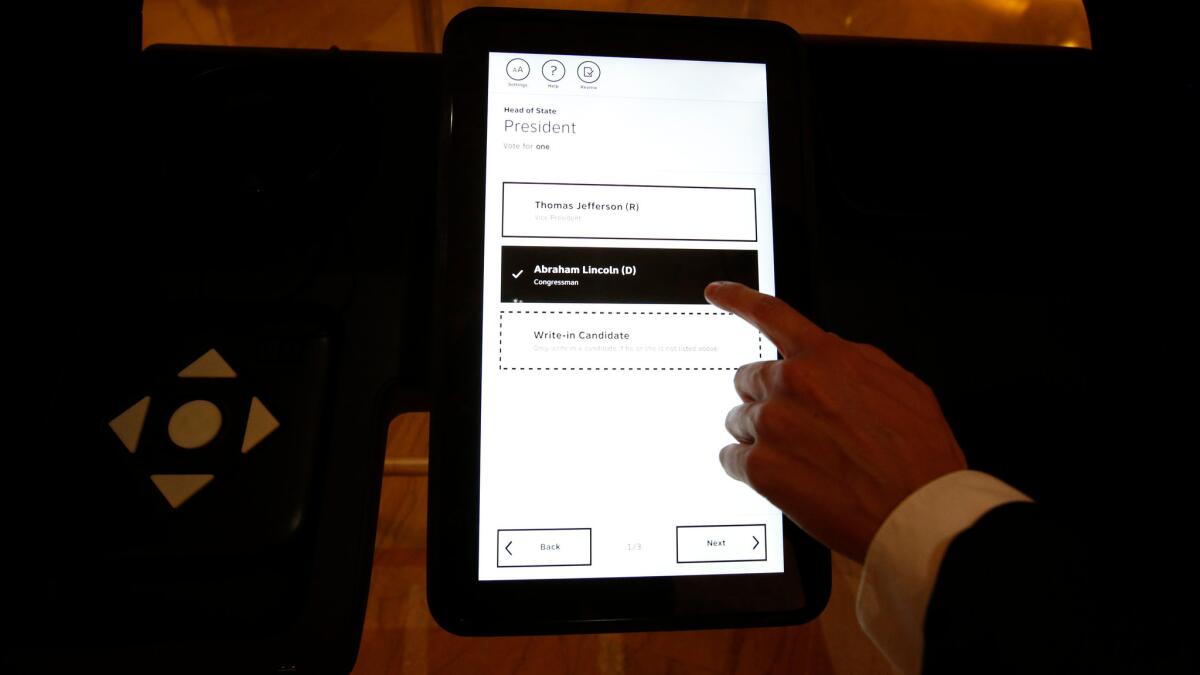

After Bush vs. Gore there was a push to modernize and computerize. In 2002, Congress established a $4-billion fund to help states upgrade their voting machines and systems. Many raced to buy and install touch-screen digital devices in the hopes they would eliminate controversy surrounding paper ballots — remember Florida’s “hanging chads”?

But as states soon discovered, digital machines can break down and are more vulnerable to hackers, software bugs and calibration errors than ones based on paper ballots. Many of the early digital machines did not keep paper backups or receipts of votes cast, making it difficult to audit results.

Over the past decade or so, states have been junking purely digital machines in favor of those that spit out paper receipts or keep a paper record of a vote.

Now most cybersecurity experts are pushing states to embrace optical scanning systems, in which voters fill out bubbles or boxes on paper, and then ballots are then scanned by machines. (Remember those Scantron tests from high school?) This method has two major benefits — paper ballots can be checked against the computerized results, and the machines tabulate votes much faster than poll workers counting by hand.

Where are hackers most likely to strike?

Battleground states. If a hacker wanted to tip the election for GOP nominee Donald Trump, he or she would not try to flip California, a strongly Democratic-leaning state, into Trump’s column because such a result would immediately raise suspicions.

If hackers penetrated the machines or voting systems in swing states such as Ohio or Pennsylvania -- which deploy digital machines, for example — to affect just a sliver of the votes, they might change the outcome in a close election.

“In a battleground state, a small nudge may have a big impact,” said Dan Wallach, a Rice University computer science professor. He urged battleground states to step up measures to guard against attacks and to upgrade to optical scanners.

Couldn’t someone hack into a state’s election results website and alter numbers as they were being reported?

They could, and it might result in some initial confusion, but it would almost certainly be detected once local jurisdictions compared their results with the state’s tally and noticed discrepancies. “That kind of hack would be caught very quickly,” said Merle S. King, executive director of the Center for Election Systems at Kennesaw State University in Georgia.

But it illustrates a bigger problem of credibility. In an election where Trump has already warned that results might be “rigged,” even an unsuccessful attempt to alter tallies could open the door to conspiracy theories and fuel questions about the election’s legitimacy for years to come.

Aren’t some votes cast online?

A small percentage of votes cast by U.S. citizens and military service members stationed and living overseas are transmitted over the Internet and thereby more susceptible to hacking. However, Merrill said those ballots are first filled out by the voter and then emailed or sent electronically to elections officials who print and then count the ballots.

While there was once a push to permit widespread online voting, election and security officials have resisted, warning it would make hacking and manipulation far easier. In light of recent hacks, the prospects for Internet voting have greatly dimmed.

Sounds like there is nothing to worry about.

Not quite. A bigger concern is that hackers might infiltrate voter-registration databases, which are frequently connected to the Internet. They could theoretically delete names, hoping to create delays or confusion on election day.

In recent months, hackers believed to be from Russia penetrated voter registration systems in Illinois and Arizona. They made off with personal data on about 200,000 people from the Illinois, forcing officials to close the registration system for 10 days, Yahoo News reported. The hacks spurred the FBI to issue a flash bulletin warning about the dangers of hacking.

“Those systems have some vulnerability because they are more connected to the Internet than voting systems,” said King. “Hacking those systems and disrupting something would certainly satisfy the goal of undermining confidence in the election, but it would not alter the course of the election.”

Election officials noted that even if a voter’s name does not appear on the rolls, federal law requires they be offered a provisional ballot and allowed to vote. Once the voter’s eligibility is confirmed, those votes must be counted. However, if a hacker managed to purge a swath of voters from the voting rolls, the resulting lines and chaos may discourage others from casting ballots.

“It doesn’t require much imagination to ponder what could happen,” Wallach said. “If you selectively disenfranchised voters that you didn’t like, you could cause havoc. Yes, provisional voting allows voters to say, ‘Your data is wrong. I need to vote.’ But they are filling out affidavits. The system is meant to handle dozens and hundreds of voters — not millions.”

What’s being done to protect against cyberattacks?

In addition to the FBI alert, Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson in an Aug. 15 phone call reminded state officials that the Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology and the U.S. Election Assistance Commission have made recommendations for securing election equipment, such as disconnecting electronic voting machines from the Internet while voting is taking place.

Election officials were also told they can call on cybersecurity experts from the Homeland Security Department’s National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center to check voting systems for vulnerabilities.

Johnson said he was so concerned about the possibility of a hack he was examining whether to declare certain parts of the election system to be “critical infrastructure,” which would free up funding and resources to help secure ballots, according to a description of the meeting released by the Homeland Security Department.

[email protected] | Twitter: @delwilber

[email protected] | Twitter: @ByBrianBennett

ALSO

‘I’m just lost.’ Voters find it hard to commit to Clinton or Trump

Obama tells voters to reject Donald Trump’s ‘outright wacky ideas’

UPDATES:

1:10 p.m.: This article was updated with comments from FBI Director James B. Comey.

This article was originally published at 8:15 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.