Charlottesville police face critics as a tense city tries to regroup from deadly weekend

Reporting from CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA. — Expressions of grief and solidarity have played out again and again in other American cities struck by tragedy — impromptu memorials of flowers and cards, prayers for the dead and injured, pledges of peace.

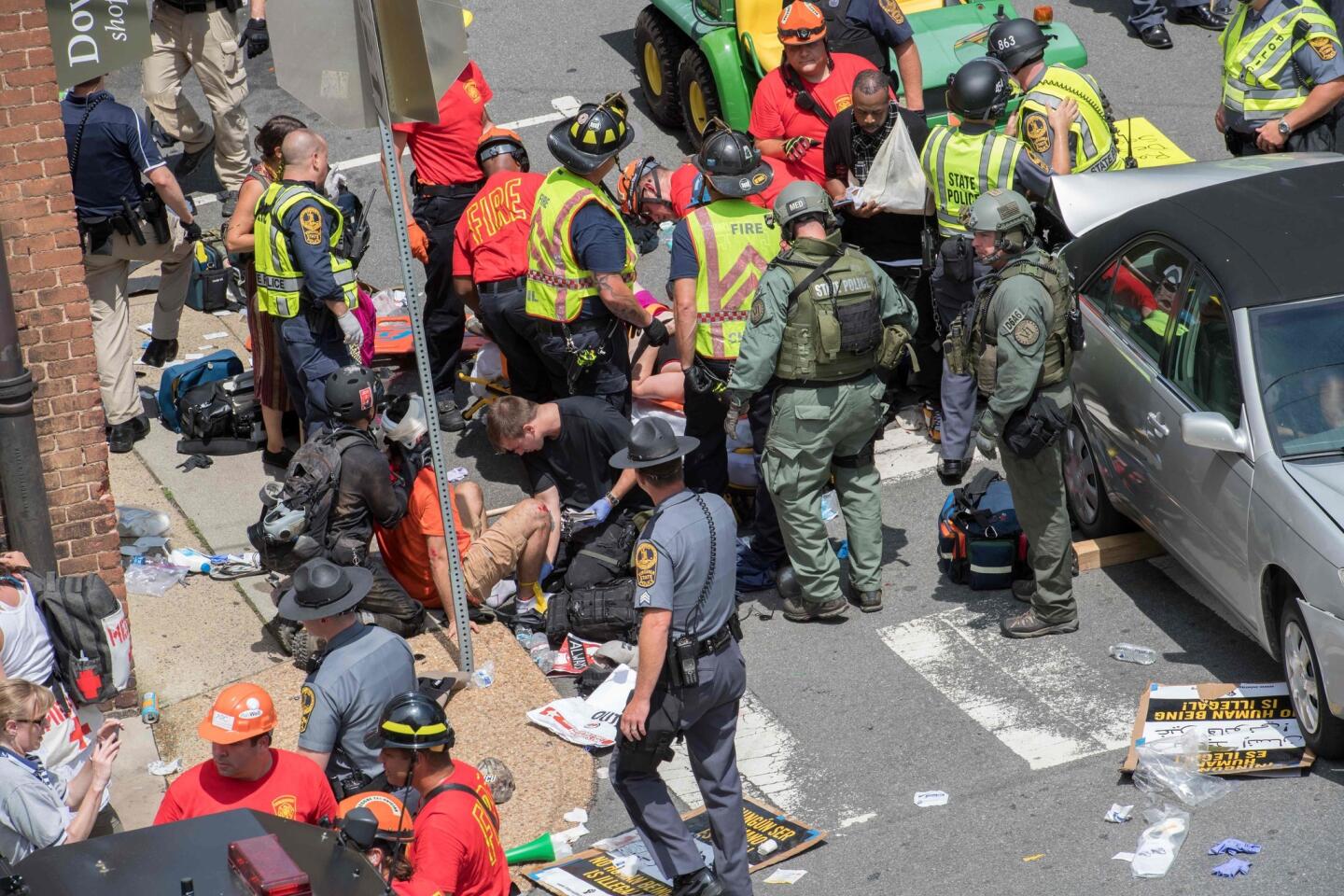

But as Charlottesville police and residents tried to piece together what led to the bloody events at a “Unite the Right” rally of white nationalists, there was the inescapable sense Sunday that the violence that left three dead and dozens injured was somehow different from previous incidents. The chaos that spread at the rally Saturday involved dozens, not just some lone guy with a grudge.

Charlottesville residents were asking whether the city and police had been properly prepared and could have prevented the deadly attack.

As the city tried to heal, officers stood guard in riot gear. Police snipers positioned themselves on rooftops.

A memorial vigil was to be held Sunday night for 32-year-old paralegal Heather Heyer, who was killed when a man said to be infatuated with Nazis plowed his car into anti-racism protesters. She had been known in the city for her civil rights activism. The vigil was postponed because of safety concerns.

Anti-racism activists are questioning why Charlottesville police, who had weeks to prepare for the permitted rally, seemed caught off guard or, in other cases, seemed to ignore violence the city had vowed to prevent. Video clips shared on social media show police standing by in some cases as brawls broke out the morning before the rally was officially set to begin Saturday.

“It’s a joke,” said Larry Engel, a local business owner, who faulted police for not separating white supremacists and anti-racist groups that repeatedly clashed before the car attack. “There was no buffer zone” between opposing groups that gathered on downtown streets and in a city park that has become an ideological battleground because of the presence of a Confederate statue.

Others defended the efforts of law enforcement. Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe, referring to the man accused of driving his car into the protesters, said, “You can’t stop some crazy guy who came here from Ohio and used his car as a weapon. He is a terrorist.”

McAuliffe also addressed those who attended the “Unite the Right” rally, which was preceded Friday night with a torch-lit march in which demonstrators chanted the Nazi slogan “Blood and soil!”

“To the white supremacists and the neo-Nazis who came to our state yesterday, there is no place for you here,” McAuliffe said, drawing an implicit contrast with President Trump, who on Saturday did not single out the same groups for blame. (The White House on Sunday said that Trump was denouncing right-wing hate groups.)

“Shame on you,” the governor said of the white nationalists, delivering his remarks at the Mt. Zion First African Baptist Church, blocks from the site of Saturday’s clashes.

Rallies also took place around the country, from Los Angeles to Miami, in support of the dozens injured in Charlottesville and the three who died, including two state police officers whose helicopter crashed Saturday.

Others, however, were quick to cast blame, including on Trump — who many demonstrators said emboldened white supremacists with nativist rhetoric — as well as on police and neo-Nazi groups.

On Sunday afternoon, angry protesters chased down one of the rally’s main organizers as he attempted to address a throng of reporters outside Charlottesville City Hall.

Members of the crowd shouted “murderer” and “shame” at Jason Kessler, a blogger based in Charlottesville, as a police sniper watched from a nearby rooftop. One man spat on Kessler and another punched him before he darted away with the help of a police escort.

In a statement, Kessler deflected blame and said the violence was “primarily the result of the Charlottesville government officials and the law enforcement officers which failed to maintain law and order by protecting the 1st Amendment rights of the participants of the ‘Unite the Right’ rally.”

Kessler, who organized the demonstration in response to the city’s efforts to take down a statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee in a park, also accused police of not doing enough to keep the two sides apart.

Alex Vitale, a sociology professor at Brooklyn College who studies policing and protests, said the strategies used by law enforcement in Charlottesville played a role in how quickly tensions escalated.

Vitale said it looked as if large numbers of police in riot gear were assigned to guard fixed barriers, which may have prevented them from moving quickly into the street and making arrests.

“They assumed that the crowds would just have their rallies and keep separate,” Vitale said.

Erroll Southers, the director of homegrown violent extremism studies at USC, said because white nationalists have become bolder in recent years, local law enforcement and government officials need to be better prepared to deal with domestic extremism and terrorism.

Southers said tensions in Charlottesville, where debates have raged over the city’s Confederate history and ties to slavery when Thomas Jefferson founded the University of Virginia, had brewed for some time.

The threat of homegrown terrorism will continue to grow, Southers said. “I see this getting worse unless the violence is taken seriously… This was a planned event. It was not a surprise. There are questions that need to be answered.”

The Charlottesville police chief, Al Thomas, declined to speak to journalists Sunday. Miriam Dickler, a spokeswoman for the city of Charlottesville, declined to address specific reports about police interactions.

“Our police officers, the Virginia State Police and other law enforcement agencies were around the area the entire day, responding to more than 250 incidents and assisting people,” she said.

One incident involved De’Andre Harris, a 20-year-old city resident who protested against neo-Nazi groups. As a gang of white supremacists was beating him bloody, Harris said, he thought he might not survive and wondered why police were not rushing to defend him.

A few moments before, he and four friends, all of them African Americans, were screaming curses at white nationalists marching along Market Street on Saturday and carrying neo-Nazi flags and yelling racial slurs.

The verbal confrontation soon turned ugly. Harris, an aspiring hip-hop artist, said he did not know why the marchers singled him out, though he had tied a white towel around his neck on which he had scrawled epithets directed at the Ku Klux Klan and police. As he fled into the nearby parking garage, the men caught up with him, hitting him with their fists and wooden poles.

But a group of police officers only a few yards away did not attempt to break up the fight, according to Harris and another eyewitness.

“They were trying to kill me out there,” Harris said. “The police didn’t budge, and I was getting beat to a pulp.”

After five or six minutes, one officer from a different group of police came to his aid.

Dozens of others were injured Saturday, including 19 people who were hospitalized after the car attack. Ten of those people were listed in “good condition” Sunday at the University of Virginia Medical Center, and nine had been discharged.

The driver — identified as James Alex Fields Jr., 20, from Ohio — was arrested and charged with second-degree murder, malicious wounding and failure to stop at the scene of an accident that ended in death.

His mother, Samantha Bloom, who lives in Toledo, Ohio, said she didn’t know that her son was attending a white supremacist rally.

“I thought it had something to do with Trump,” she told the Toledo Blade, saying she avoided getting “too involved” in her son’s political views. The family moved to Ohio a year ago for the mother’s job, she said.

Derek Weimer, who was Field’s high school history teacher where he grew up in Kentucky, told WCPO-TV in Cincinnati that Fields had been “infatuated with Nazis” and had “radical ideas on race.”

On Sunday, the U.S. Army spokeswoman Lt. Col. Jennifer Johnson said Fields reported for basic military training in August 2015 but was “released from active duty due to a failure to meet training standards” just four months later.

Photos circulating on social media appeared to show Fields posing with members of Vanguard America, a white nationalist group, on the day of the rally. Fields held a black-and-white shield with the organization’s insignia. Vanguard America said Fields was not a member and that shields were distributed widely.

More details also emerged about the two state troopers killed when a State Police helicopter crashed near the city after monitoring the chaos.

H. Jay Cullen, 48, was a veteran of the force who spent years flying the governor around the state. Berke M.M. Bates, 40, was just beginning a career as a helicopter pilot that he had dreamed about for decades. He would have celebrated his 41st birthday Sunday.

Times staff writers Cloud reported from Charlottesville and Kaleem and Etehad from Los Angeles. Times staff writer W.J. Hennegan contributed reporting from Washington, D.C.

ALSO

Opinion: Here’s what UVA did wrong when white supremacists came to campus

‘She died doing what was right:’ Details emerge about those killed in Charlottesville

Hip-hop artist recalls his beating in Charlottesville: ‘They were trying to kill me out there’

UPDATES:

8:10 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details and comments from De’Andre Harris, Jennifer Johnson, Erroll Southers and Miriam Dickler.

3:50 p.m.: This article was updated with complaints about the police’s handling of events as well as with details about the victims and suspect.

This article was originally published at 9:55 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.