Hits, but mostly misses, are in the trading cards

Collectors hoping to unseal a victory take their chances on boxes of cards on trading night at Spokane Valley Sportscards in Washington state.

At Spokane Valley Sportscards, collectors come once a month for their version of a poker night, breaking open factory-sealed boxes of cards, looking for what they call a hit. They may have different teams they favor, but they're all after big-name players, the ones whose cards could command hundreds of dollars.

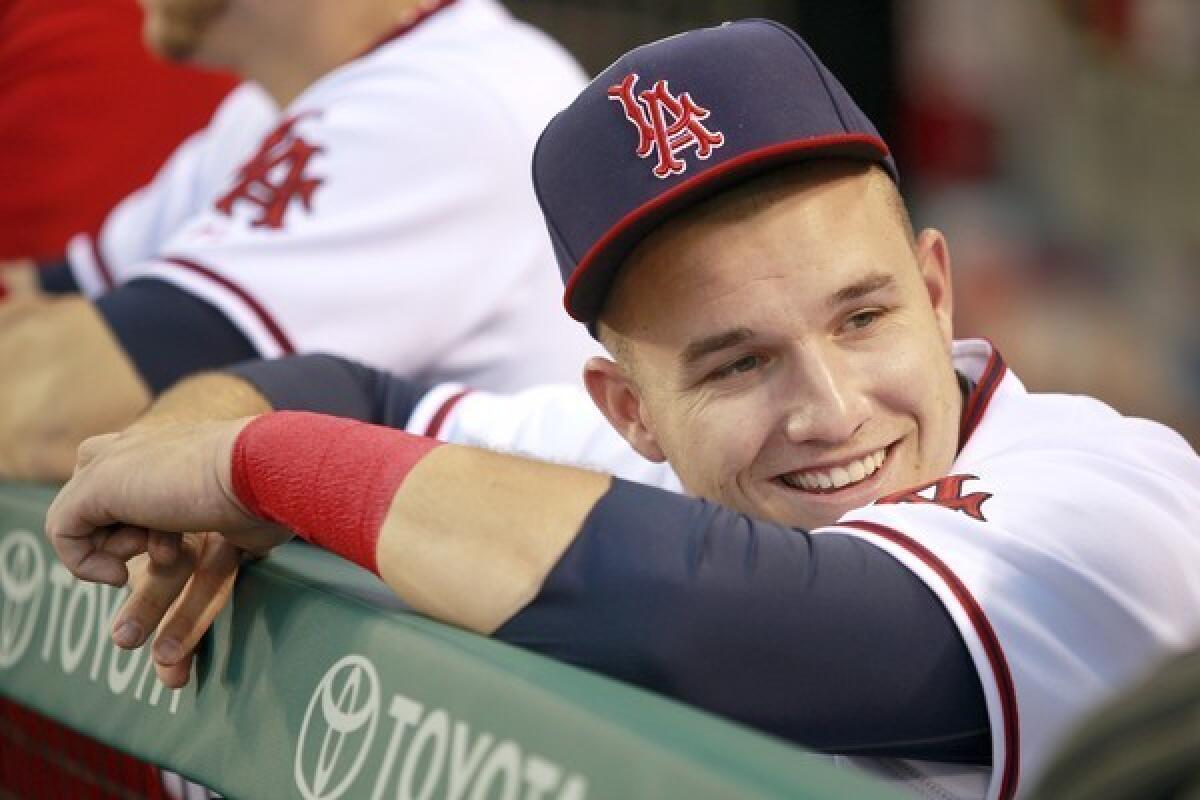

Among the regulars, Joseph Branda is known as the risk-taker.

He's the one who once bought a $600 box of basketball cards, the kind that comes in an intricate wooden chest. He's the one with the collection that's potentially worth as much as a decent car. On this Saturday, as the others hold back their spending, he's the one who just asked for another box of football cards, wagering $140 on coming away with a prized addition to his collection.

Leaning over a counter, Branda, 22, quickly sorts through the box. He rips open six packs, each holding six cards, and flips through a lineup of professional football players.

He tosses aside most of them, even an autographed card of Denver Broncos running back Ronnie Hillman that he'd later sell for $10 online, and one of Minnesota Vikings offensive lineman Matt Kalil he'd sell for $5.

Then Branda's eyes widen. He tilts his head back and breaks into a stunned smile.

"RG III!" he calls out.

It's a hit. He's scored Robert Griffin III, a Heisman Trophy winner and starting quarterback for the Washington Redskins. The limited-run card is autographed. It also has a swatch of his jersey attached to it.

All conversation in the room stops, and several of the others huddle around him. They gawk at the card.

"Whoa!"

"Oh, that's awesome!"

The shop's owner, Alan Bisson, looks up the value: $150.

Bisson takes the card held in Branda's trembling hand. He slips it into a plastic cover to protect it.

"That's what I'm looking for!" Branda says. "Every hit from here on out is profit."

The third Saturday of each month is trading night, when baby boomers gather alongside college students and kids too young to have seen Michael Jordan play basketball.

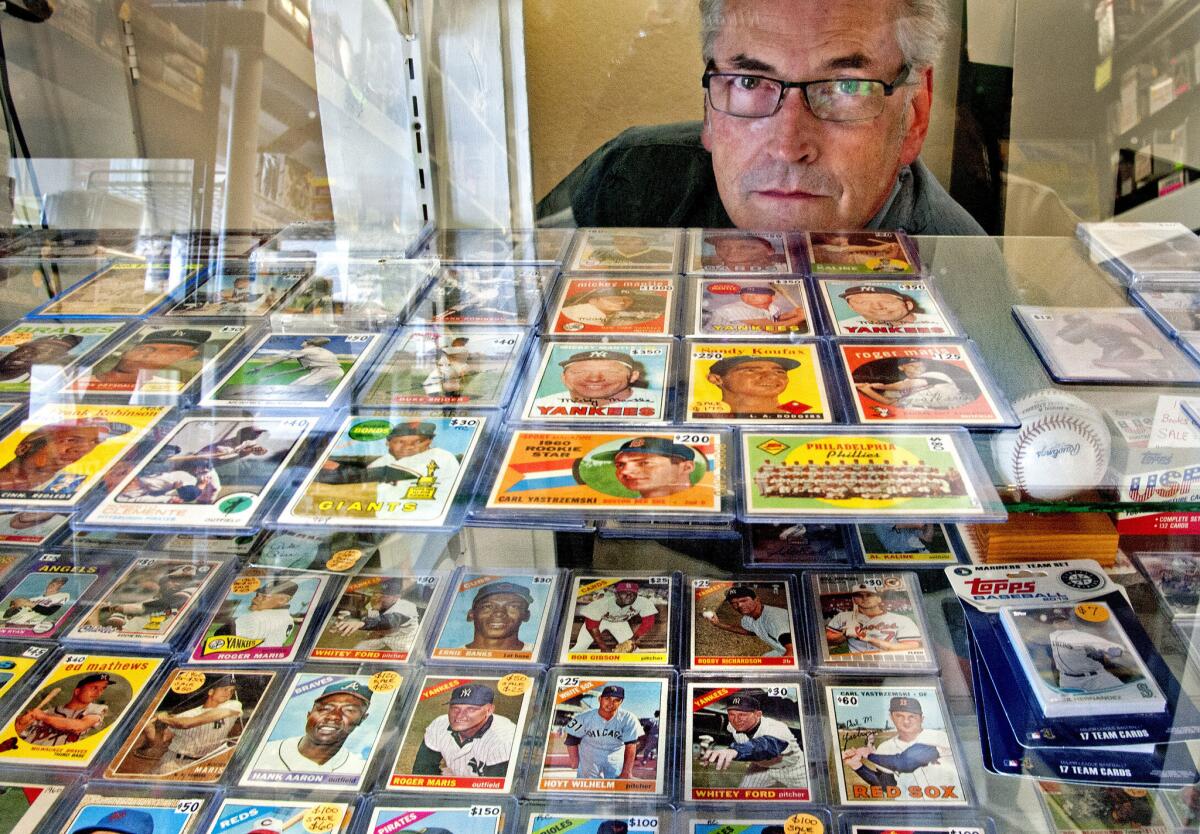

"It's like pulling the handle on a slot machine," Alan Bisson says of buying sports cards. "It's the chance of pulling the big one." (Dan Pelle / Spokesman-Review) More photos

The regulars who come to Bisson's shop — a group of no more than a dozen, sipping on the root beers he sells for 50 cents a can — are not very interested, however, in making trades.

They've been lured here by the thrill of the hit. They come month after month, hoping they will turn up one of the cards conceived as collectibles, with limited quantities inserted into random packs. Some are affixed with pieces of the player's bat, jersey, even helmet to bump up their worth.

"It's like pulling the handle on a slot machine," says Bisson, 60, who admits that he's one of his own best customers. "It's the chance of pulling the big one."

His passion (or vice, depending on how you look at it) is what drew him into this business. Twenty years ago, the salesman at the shop where Bisson bought his cards wanted to branch out on his own. He asked a few of his patrons — including Bisson, then working as a photographer — to go in with him.

Bisson's the only one still in the business. He runs the store — which focuses on sports memorabilia but also carries political collectibles — from an old ranch-style house in this Spokane suburb.

In what was once a cozy living room, racks of card boxes block the windows, and the fireplace is hidden behind shelves of merchandise, including a football autographed by Barry Sanders, and mini-helmets signed by William "Refrigerator" Perry and Russell Wilson. In the den, a worn, sea-green sofa faces a wall overtaken by Bisson's version of a library card catalog, where the cards of almost any athlete a collector might be looking for are organized in alphabetical order: Troy Aikman. Kobe Bryant. Jay Cutler.

It's a better hobby than doing drugs and being in a gang. So they approve of that."— Scott Brewster, on how family and friends, especially wives and girlfriends, view the trading-card hobby

On good days, maybe a dozen people walk in. There are many days, though, when it's just Bisson, propped on a stool behind the case of baseball cards that serves as a counter as he sorts and prices his inventory.

A number of those who show up are looking to sell rather than buy. Their collections usually date to the early 1990s, when sports cards were a fad. Now they've got boxes of overproduced memorabilia that is as good as garbage, as Bisson tells one man who lugged in his collection one afternoon.

"You can't give them away," he tells the disappointed man. "I hate to say it's junk, but that's what they're considered."

Still, before the man leaves, Bisson sorts through every last card. Odds are he won't find anything. But he never passes up an opportunity — no matter how unlikely — to search for a hit.

Most of the card business, Bisson says, has moved online. He has a little studio set up in the back to photograph memorabilia. It's just not the same. The serendipity of the experience isn't there; neither is the sense of community.

He could have walked away, like his former partners and the owners of other shops in the area. At the moment, trading night keeps the shop afloat.

Many of the regulars were about Zach Croall's age when they started collecting. Zach, 9, may be the youngest, but he's just one of the guys.

When he runs to tell the others of his hit — a card for Detroit Lions quarterback Matthew Stafford, numbered 17 of 25 — they root him on. "Oh, gorgeous!" one of them says. The card is worth about $60.

Alan Bisson, left, and his trading night customers open packages of sports cards in hopes of scoring valuable cards, known as hits. (Christopher Anderson / For The Times) More photos

Zach has been coming since December, driven by a passion for sports that he picked up from his father, a New England Patriots fan.

"Instead of watching cartoons in the morning," Zach says, "I get up and watch 'Sports Center.' "

His father, John, says he originally came for his son, but now he's as invested as Zach, if not more so. He wants to build a collection of Patriots memorabilia that he can pass on to his children.

At some point, many kids outgrow the hobby. Branda has inherited many of his friends' collections. He has about 400,000 cards of football, basketball and baseball players, organized in plastic bins that stack to the ceiling of his bedroom.

The regulars say their family, their friends — wives and girlfriends, especially — don't get it: Why would they spend so much money on cards?

"It's a better hobby than doing drugs and being in a gang," says Scott Brewster, a 20-year-old junior at Washington State University. "So they approve of that."

Their expensive hobby also has the potential for profit. Branda, who has ambitions of attending business school and becoming a general manager of a pro team, is quick to sell cards and invest the money into buying new ones. He would sell the Griffin card for $90.

He has also sold a card featuring the autographs of eight Yankees who played in the 1996 World Series — the second of two made — for $750. Brewster made $300 in profit on a card with the autographs of the NBA's San Antonio Spurs Tim Duncan and David Robinson he bought for $25 at a yard sale.

As trading night winds down, Branda buys one final box of baseball cards.

A customer flips through cards on trading night in search of a winner. (Christopher Anderson / For The Times) More photos

Brewster thought he was done for night, but he decides to split the $90 box with Branda and two others. He's dipping into his rent money now. Each collector gets a division and the cards are doled out accordingly.

Branda says he started collecting because of his grandmother. He has always been an athlete, but she wanted him to have another hobby as well. Collecting cards, he says, seemed at the time almost as good as playing a sport.

"Oh, yes!" Brewster calls out.

He's got a hit. This time it's one of sentimental value. It's Conor Jackson, a former outfielder for the Arizona Diamondbacks. Brewster has rooted for the team since it won the 2001 World Series, when he was living in Yuma, Ariz.

The regulars finish the box, and the night.

Bisson writes their charges on slips of paper and adds up the tab. One of his better customers racks up a tab so big — $643.50 — that he doesn't want the amount printed with his name for fear of reprisal from his wife.

For Branda, it's $260. For Brewster, $140. He pays some of it with his debit card, a little more in cash. He will take care of the rest when he's back next month, flush with more money and ready to try his luck again.

Follow Rick Rojas (@RaR) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

In Mexico, she fights crime, runs afoul of the law

She had more right to be the leader because she has more guts than any man."

Some Syrians rebuild amid the ruins

They are rebuilding with faith in God and hope in the revolution that soon it could be over."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.