Black scientists respond to Scalia’s suggestion that ‘less advanced’ classes are more suitable

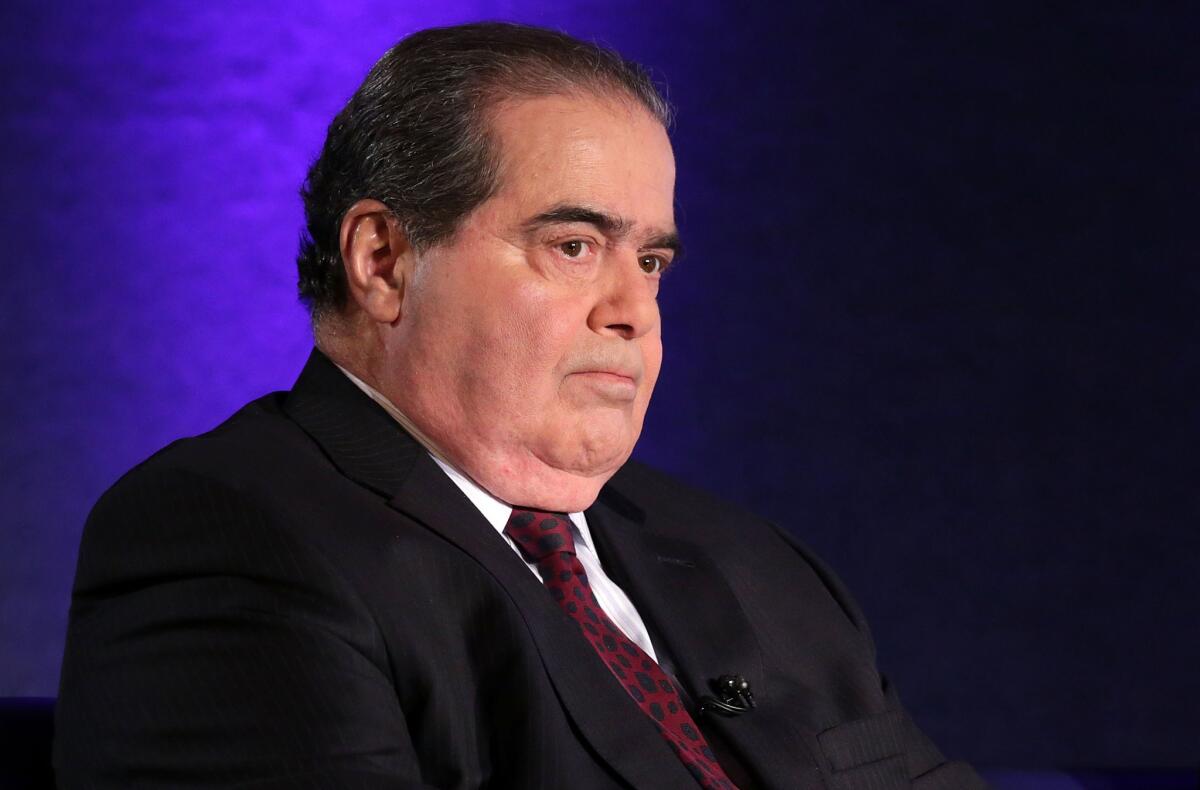

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia suggested during oral arguments Dec. 9 that a school such as the University of Texas was too taxing for black students, and that they might do better at “a less-advanced school, ... a slower-track school.”

When Chanda Prescod-Weinstein left her home in Los Angeles and headed off to Harvard for her freshman year, the undercurrents were both predictable and fierce.

“You only got in because you’re black,” classmates told her. If not for affirmative action, they said, you’d never be a student on a campus like this.

They were wrong.

Prescod-Weinstein went on to write her doctoral dissertation, “Cosmic Acceleration as Quantum Gravity Phenomenology,” at the University of Waterloo in Canada and is now a research fellow studying theoretical cosmology at MIT.

Along with other black students, scholars and scientists across the country, Prescod-Weinstein stands in glaring contradiction to the legal reasoning of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, who in oral arguments in a Texas affirmative action case this week suggested that a school such as the University of Texas at Austin might be too taxing for black students. He said they might fare better at a “less-advanced school ... a slower-track school.”

Speaking from the bench, Scalia went on: “Most of the black scientists in this country don’t come from schools like the University of Texas. They come from lesser schools.”

Scalia’s words drew a sharp rebuke from Prescod-Weinstein and other black scholars who felt stung by the thought that they were somehow unprepared for the rigors of math and science and that affirmative action was just code for a lack of quality.

The Texas case, in which a white student alleges that she was passed over for admission to make room for minority applicants, has again made affirmative action part of the national conversation and has awakened old arguments.

In his comments, Scalia appeared to be referring to the “mismatch theory,” which argues that affirmative action actually harms some minority students by admitting them to schools where they’ll compete against classmates with far higher admission test scores.

Students who enter college under such circumstances, the theory holds, will probably be academically overmatched, potentially contributing to the dearth of black scientists.

Elizabeth Wayne is among those who reject such thinking and believe the challenges for black students run far deeper.

Wayne, a University of Pennsylvania graduate who has a doctorate in biomedical engineering from Cornell University, recalled that if her white classmates performed poorly, professors might offer them tutoring or coveted research opportunities to help get them up to speed. “They would give them the benefit of the doubt,” she said.

She felt she did not have that luxury. “I had to be at the top of my class, or people would think I didn’t belong there.”

Wayne, who discusses race in her podcast called “PhDivas,” fears Scalia’s statements could justify discrimination and erode educational opportunities for minorities.

“What if the admissions officer at University of Pennsylvania had said, ‘She’s black; there’s no way she’ll do well in a physics program at a prestigious university’?” she said. “What if they thought they were doing me a favor by not accepting me?”

Prescod-Weinstein pointed to a 2010 study of MIT faculty that showed that 59% of all underrepresented minorities in science departments came from either MIT, Harvard or Stanford. The University of Texas at Austin, which Scalia suggested was too fast-paced for some black students, was not on the list.

Although a “mismatch” in preparedness may be a small factor for any student struggling in a classroom, the MIT report concludes that a large hurdle facing black science students is that schools simply don’t think they belong there.

More than half of black faculty members at MIT reported being mistaken for support staff, the study found, and nearly half reported being mistaken for a trespasser — someone who didn’t belong on campus at all.

Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of the Hayden Planetarium in New York and host of last year’s documentary series “Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey,” describes the alienation he felt as a black child who showed an interest in astrophysics.

“Teachers would say, ‘Don’t you want to be an athlete?’” he recalled in a video that went viral last year.

Scalia wasn’t the only justice whose comments on the affirmative action case seemed off-key to some.

“What unique perspective does a minority student bring to a physics class?” wondered Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.

Wayne, now a research fellow at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said Roberts’ question could easily be interpreted as: How can white students benefit from having a black face in the classroom?

The remark was ironic to Sylvester James Gates Jr., a theoretical physicist at the University of Maryland at College Park. He has written more than 200 scientific publications and is known for his work in supersymmetry, supergravity and superstring theory.

“The same unique perspective I have and that has apparently allowed my research to create never previously known forms of mathematics … showed up when I was a minority student in a physics class,” he said in an emailed statement to The Times.

He would not be where he is today, he said, without informal affirmative action policies that began in 1969 and helped him gain entry to MIT, where he earned his bachelor’s and doctorate degrees.

“Diversity,” he said, “often contains the seeds of innovation.”

ALSO

Long-distance lottery win throws Oregon officials for a loop, but Iraqi man prevails

Accused deserter Bowe Bergdahl gives ‘gripping’ details of captivity on ‘Serial’ podcast

After terror attacks, Muslim women say headscarves have made them targets for harassment

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.