This anarchist and ‘anti-fascist’ activist is using facts to go after the far-right fringe

Self-proclaimed anarchist and ‘anti-fascist’ Daryle Lamont Jenkins runs a website called the One People’s Project. Jenkins has published unflattering information he’s gathered on far-right figures since 2000. (March 1, 2017)

Reporting from National Harbor, Md. — The young man practically squealed when he saw Richard Spencer, one of America’s most famous white nationalists, standing in a hallway at the Conservative Political Action Conference.

“Oh my god, oh my god, oh my god, he’s here!” said J.P. Sheehan, a conference attendee in a black “Make America Great Again” hat, hopping up and down. Sheehan held up a maroon T-shirt for Radix, the online journal published by Spencer, who has called for a separate nation for white people.

“He’s literally, like, the coolest guy,” Sheehan said.

But as reporters circled Spencer, a heavyset man in a plaid shirt pointed a phone camera at Sheehan. The young man’s bubbly energy turned standoffish. “Can I help you, Daryle?”

On hearing his name, Daryle Lamont Jenkins, 48, of Philadelphia smiled.

“If you know my name, then you know how you can help me,” Jenkins said, snapping a photo of Sheehan.

Of the thousands of people who visit CPAC each year hoping to network with fellow conservatives and listen to speeches by prominent Republican members, Jenkins is one of its most unusual attendees. Jenkins is an anarchist, and he runs a website called the One People’s Project, where he publishes information he’s gathered on far-right figures since 2000.

It’s a modest operation. Jenkins is not widely known, except among the white nationalists he monitors. He has a couple thousand Twitter followers, and until recently, he was a delivery truck driver. He paid his own way to attend CPAC in Maryland last week.

These are busy times for activists who identify themselves as “anti-fascists,” as Jenkins does. President Trump’s comments on Muslims and immigration have energized white nationalists, and their fringe rhetoric has found a more prominent stage online and in the media.

At the same time, recent months have also shown the limitations of the far-right’s ability to advance safely into mainstream spaces.

The “alt-right” — a loose-knit movement of white nationalists, neo-Nazis and misogynists — splintered after footage went viral showing Spencer receiving Nazi salutes at a conference for white nationalists shortly after Trump’s election in November. In February, the British provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos lost his speaking engagement at CPAC and a book deal after video emerged showing him apparently promoting pedophilia.

In both cases, facts, not fists or firebombs, arguably dealt the biggest setbacks, prompting people and institutions to distance themselves from Yiannopoulos and Spencer (who was asked to leave CPAC shortly after arriving). Jenkins wants to bring that type of damaging information to light, and so he shows up at right-wing events to photograph and document notable attendees — half activist, half reporter.

“That journalism part is really important,” said Jenkins, who says he works with other volunteers but wants to keep their identities secret for their protection. “We have to put out the facts as they are.”

The final product can be an odd mix. Jenkins’ website sometimes veers between dispassionate writing and bombast. The recent death of a Missouri Ku Klux Klan leader bore the headline, “Frank Ancona, Rot in Hell!” But the story that followed was written like a just-the-facts newspaper story.

One of his site’s most notable scoops came in 2009, when he published court records showing that the executive director of a conservative political action committee, Marcus Epstein, had been charged with assaulting a black woman and calling her the N-word.

Epstein pleaded guilty to simple assault in connection with the incident, and the case soon appeared on the website of the Southern Poverty Law Center and in the New York Times. One of Epstein’s supporters, Bay Buchanan, compared the public backlash to a “modern-day lynching.”

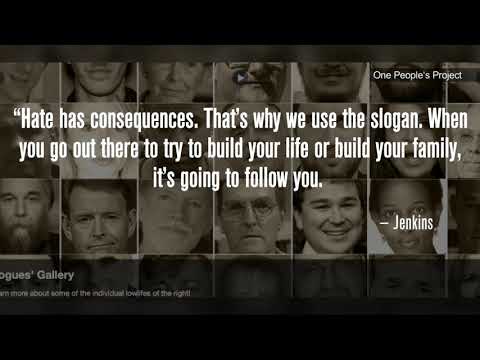

Jenkins believes in shaming with information. Joining the alt-right today could mean getting turned down for a job tomorrow if an employer punches someone’s name into Google and finds it on Jenkins’ website. His slogan: “Hate has consequences.”

“A lot of those folks that are subscribing to the alternative right are relatively young, and they don’t know that this isn’t going to last,” Jenkins said. “When you try to go forward in your career, this is going to come up.”

That’s why Jenkins drove to CPAC, a gathering for Republican activists of varying ideological stripes. He sees CPAC as something more, a chance for fringe types to also network, gossip and raise their visibility.

Toting a black laptop bag, Jenkins patrolled the halls like a leftist Ghostbuster, watching for any budding white-power radicals to reveal themselves among the young conservatives in heels or blue blazers and neat haircuts.

“Where there’s smoke, there’s fire,” Jenkins said.

He looked over at Spencer, the white nationalist, and focused on faces nearby, wondering whether Spencer had brought an entourage. He continued snapping photos.

“Everybody knows who Spencer is, so I look for everybody who’s around him.”

Jenkins sifts through a lot when scanning a crowd. At CPAC, one young, clean-cut conference attendee, clutching his conference badge to his chest — flipped over, so his name wouldn’t show — tried to take a photo of Spencer without anyone noticing.

A fan of Spencer’s or an adversary? When a reporter asked who he was associated with, the young man mumbled that he was just an attendee and walked away, keeping his badge flipped over and his name out of sight.

Jenkins muttered to himself as he spied a woman talking to reporters near Spencer. “What’s this conversation about?” He listened. “She’s defending Milo” Yiannopoulos. Jenkins decided to move on.

He sidled up to a young man with a “Free Milo” sticker on his badge and challenged him in conversation. “I don’t like this confrontation,” the young man said, initially cowed. But Jenkins assured him it wasn’t a confrontation, and the pair carried on a debate about politics, and Jenkins didn’t record him.

CPAC staff also hovered nearby, watching Spencer anxiously.

“They’re trying to figure out what they’re gonna do about this,” Jenkins murmured. “As long as Richard Spencer is around, he’s going to create crowds like this, and he’s going to make the conference look bad.”

Spencer got the boot about 20 minutes later.

“The alt-right does not have a legitimate voice in the conservative movement,” CPAC organizer Matt Schlapp told reporters shortly before a security guard came to kick Spencer out. Jenkins followed behind Spencer, camera in hand, until Spencer left the premises.

Jenkins’ opponents on the far right have criticized him repeatedly over the years, variously attacking him for his weight, for posting phone numbers and addresses, and for “irrelevant posturing” by publishing “‘outings’ of minor costume Nazi and scenester types who revel in the attention,” the far-right site Occidental Dissent wrote in 2010. Yet they seem to agree he is, at minimum, an irritant.

Jenkins said he often received emails from people asking him to remove their names from his website. “Usually I get the email, ‘Please, I’ve grown up. I don’t want this hurting me any further.’” Jenkins said he often removed the information.

“Really, the only condition is that you’re not involved any more,” Jenkins said. “I just want you to stop being a Nazi! Is that too much to ask?”

Jenkins’ site now features a photo of Sheehan, the young Spencer supporter, who was quoted in news reports about his enthusiasm for seeing the white nationalist. The Times decided to ask how he felt about it.

But when a reporter sent an email this week to Sheehan’s chapter of the College Republicans at Western Connecticut State University asking for a way to contact him, a representative, Christy Petriccione, replied, unprompted, that Sheehan had been asked to resign from the group. The college Republicans, she wrote, “disavow and have no relation to him anymore.”

Later, The Times reached Sheehan by email, where he declined to be interviewed. He asked to not even be mentioned. (The Times declined and pointed out that he had previously given interviews to other national outlets, including to Slate at CPAC. In the Slate interview, he said he was 26 years old and defended the alt-right movement as “identity politics for white people.”)

“I’ve already made the mistake of putting my friends through a lot, and so I would really appreciate it if you didn’t mention me,” Sheehan wrote in a message on Monday. “It would only make the situation worse for my friends who do not share my views and don’t deserve to be dragged into this.”

When told Tuesday of the apparent backlash against Sheehan, Jenkins chuckled.

“Hate has consequences. That’s why we use the slogan,” Jenkins said. “When you go out there to try to build your life or build your family, it’s going to follow you. People are going to look you up online … and your career stops right there.”

ALSO

DeVos’ CPAC speech, an L.A. school board voter guide, Apple on Trump: What’s new in education today

Trump lays out ambitious plans for healthcare and immigration in a disciplined speech to Congress

White nationalist leader Richard Spencer booted from Conservative Political Action Conference

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.