‘Whitey’ Bulger, notorious Boston mobster-turned-fugitive captured in Santa Monica, is dead at 89

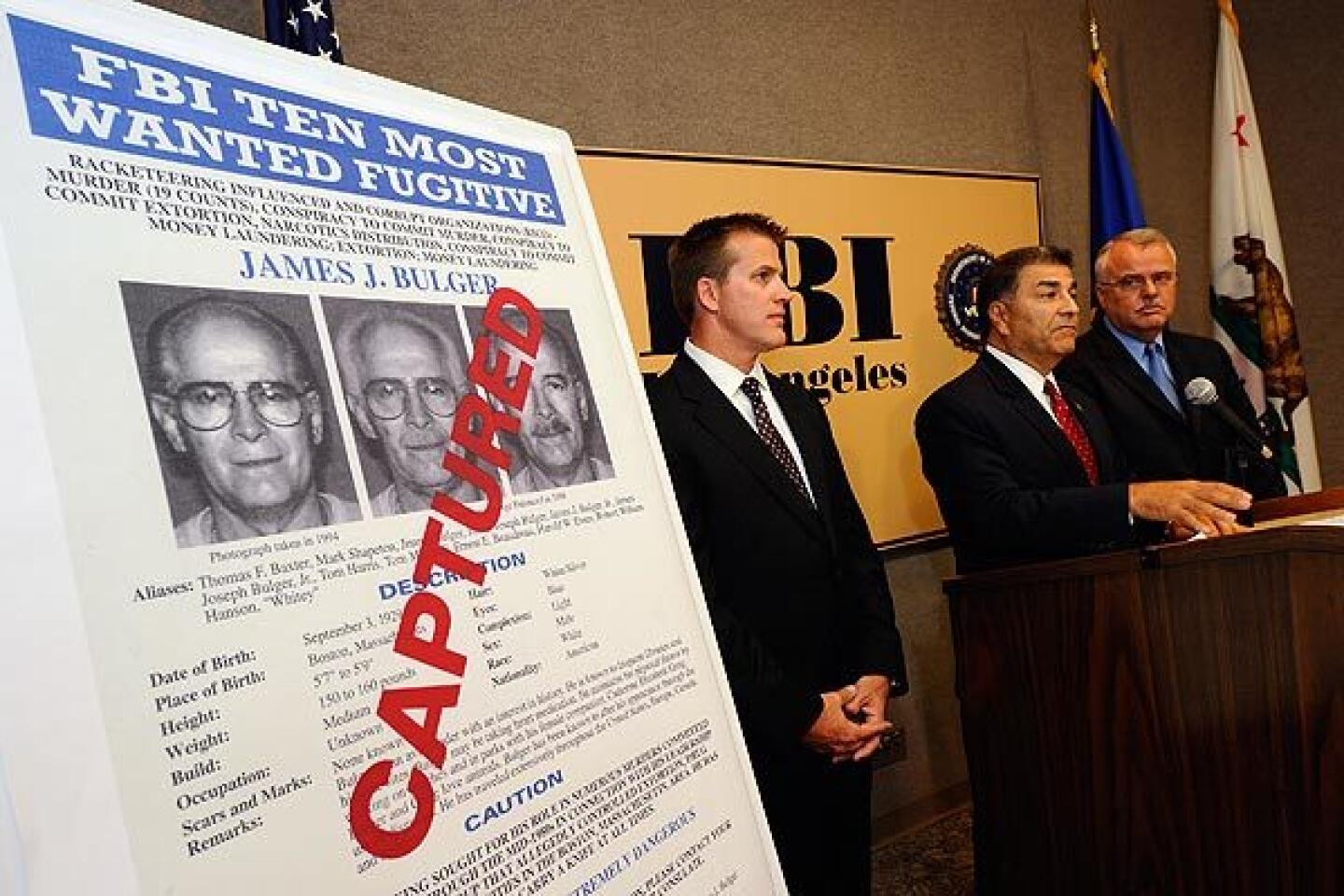

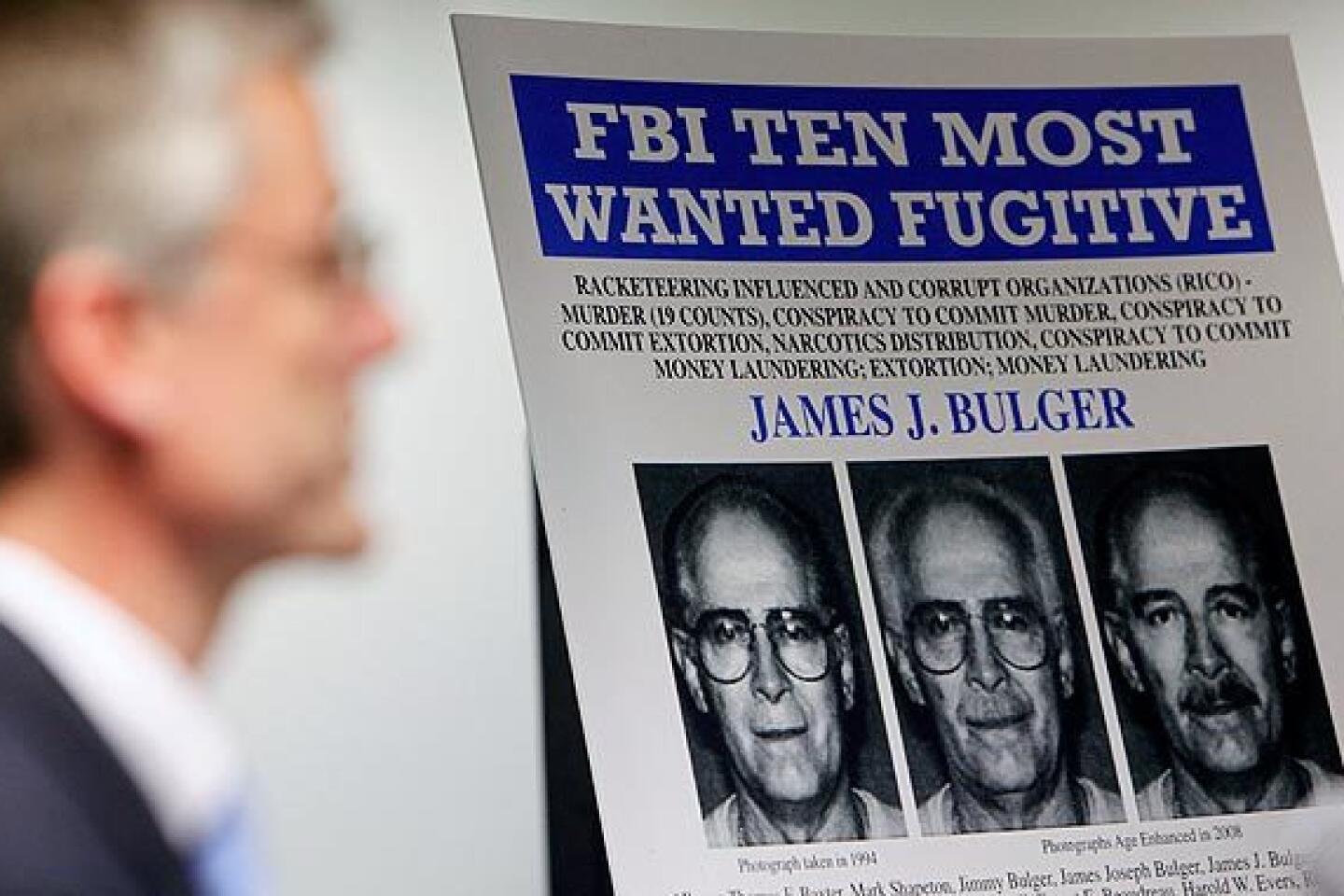

James J. “Whitey” Bulger Jr., the ruthless Boston mobster who topped the FBI’s most-wanted list and was found quietly living as a fugitive near the ocean in Santa Monica in 2011, has died in prison, according to the Federal Bureau of Prisons. He was 89.

Bulger was found unresponsive early Tuesday in his prison cell at United States Penitentiary Hazelton, a high-security prison in West Virginia where the aging mobster had been moved just the day before. A prison union official said Bulger’s death is being investigated as a homicide. The FBI is investigating.

Bulger and his longtime girlfriend, Catherine Greig, lived under assumed names for nearly 16 years in a two-bedroom apartment near Santa Monica’s Third Street Promenade. They were known as Charlie and Carol Gasko, and their acquaintances thought they were retirees from Chicago.

In fact, Bulger had been the subject of a global manhunt since fleeing Boston in 1995 after he was tipped off to his federal indictment by a former FBI agent. Bulger claimed after his capture that federal authorities had secretly granted him immunity from prosecution for all crimes past and present, but his argument was thrown out of court in 2013 and a Boston jury found Bulger guilty of 11 murders and numerous counts of extortion and racketeering.

His case was the subject of a congressional inquiry on whether FBI agents in Boston enabled their underworld informants to do whatever they felt advanced their illicit businesses, including murder. John Connolly Jr., Bulger’s main FBI handler, was later sent to prison for his role in Bulger’s flight and in a Florida killing.

Born in Boston on Sept. 3, 1929, James Joseph Bulger Jr. was raised in tough South Boston and dropped out of school in the ninth grade. He served in the Air Force and later did time at Alcatraz and other federal prisons for bank robberies. His brother William Bulger became one of the most powerful politicians in Massachusetts, serving 18 years as president of the Massachusetts Senate and eight years as president of the University of Massachusetts.

Bulger inspired many TV and movie productions, including the 2006 Academy Award-winning film “The Departed.”

Bulger managed for 16 years to elude federal authorities, who had targeted him with a $2-million reward and tracked down false leads of his fleeting presence on nearly every continent. When Osama bin Laden was killed in 2011, Bulger moved to the top of the FBI’s most-wanted.

Two years later, Bulger was convicted in Boston of 11 murders as well as extortion and racketeering schemes that allegedly netted him more than $25 million. Greig was sentenced to eight years in prison for helping Bulger in his flight. An additional 21 months was added to her sentence in 2016 when she refused to testify before a grand jury.

Since 1996, Bulger had hidden in plain sight as Charlie Gasko, an avuncular geezer who handed out miniature flashlights to neighbors but also warded them off with a “Do Not Disturb” sign on his apartment door.

Bulger as Gasko was cantankerous, but friendly enough to give a black Stetson hat to his guitar-playing apartment manager. He loved to stroll Santa Monica’s busy Third Street Promenade and he was lucky enough to rent an affordable apartment just blocks away.

Ultimately, the charismatic hoodlum who ran a criminal empire under the nose of federal authorities and whose lavish gifts to FBI agents were exposed in criminal and congressional hearings, was brought down by his girlfriend’s concern for a stray cat.

In 1995, Bulger and Greig fled Boston after former FBI agent Connolly, an old family friend who grew up in Bulger’s tough South Boston neighborhood, tipped him to his coming federal indictment.

Traveling around the country for more than a year under various aliases, the couple found their apartment in a Santa Monica building called the Princess Eugenia. Agents who raided Apartment 303 on June 22, 2011, found 30 guns and more than $822,000 in cash stashed in holes Bulger had cut neatly in the walls. An unfinished memoir was on the nightstand.

Bulger had been featured 15 times on the “America’s Most Wanted” TV show. An FBI task force had sought him for years. But in 2011, when authorities ran daytime TV ads that focused on Greig, an acquaintance named Anna Bjornsdottir responded immediately. Bjornsdottir, a yoga instructor and former Miss Iceland, knew Greig as Carol Gasko, the nice woman from across the street who befriended an abandoned tabby named Tiger. She knew Bulger as Charlie Gasko, a sour, bigoted old man who dropped no hints about his past.

Bulger’s story had epic qualities. He grew up poor in a family that became one of the most powerful in Massachusetts. Younger brother William was forced out of his university post by his fugitive brother’s notoriety.

Meanwhile, Whitey, whose nickname reflected his boyhood shock of blond hair, had become a bank robber and served time in Alcatraz. Drifting back to the neighborhood after his parole in 1965, he was seen by some as a kind of Robin Hood, a criminal who protected his weaker neighbors and stole mostly from those who were thought not to deserve deserve their good fortune.

“You had a husband giving a wife a hard time, that’s the stuff you went to him for,” Peggy Davis-Mullen, a Boston City Council member from Bulger’s old neighborhood, told The Times in 1999. “You knew that he was a guy involved in organized crime but you also had — I’ve got to be honest with you — regard for the man. I don’t know what he did when he was doing his business, whatever his business was, but I know that he was a guy on the street and that he was good to people who were poor.”

The portrait of him that emerged at his 2013 trial wasn’t quite so exemplary.

Bulger was convicted of fatally shooting rival gangsters, suspected informants and bystanders who simply got in the way. He chained alleged jewel thief Arthur “Bucky” Barrett to a chair, interrogated him about hidden cash and then shot him in the head. He strangled Deborah Hussey, the daughter of his henchman Stephen Flemmi’s girlfriend, because he thought she had a big mouth and would implicate him in crimes.

In testimony and court filings, witnesses described Bulger’s murders not only as business decisions but also as acts that he relished, sometimes taking a nap while Flemmi yanked out the teeth of the dead to make identifying them more difficult.

Others spoke of threats: Bulger telling a restaurant owner that he’d cut off his ears and stuff them in his mouth if he didn’t come up with his loan payments; Bulger taking over a South Boston liquor store after plunking his gun on a table, hoisting the owner’s 2-year-old daughter onto his lap, and saying it would be a shame to not see her grow up.

Over the years, Bulger’s cinematic life story drew interest from Hollywood. With Jack Nicholson portraying a Boston mob boss based partly on Bulger, “The Departed” won four Academy Awards in 2006, for best picture, screenplay, editing and directing by Martin Scorsese. In 2015, Johnny Depp played the Bulger-inspired character in “Black Mass.”

Bulger was the son of a laborer who lost an arm hopping a train. As a boy, Bulger fought constantly and broke into homes. A year after he left reform school in 1948, he enlisted in the Air Force and, despite a spotty disciplinary record, was honorably discharged in 1953.

Back on the streets, he robbed banks in Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Indiana, and did time in several federal prisons, including one in Atlanta where he participated in a researcher’s LSD experiments. He served nine years of a 20-year sentence, securing an early release with the help of his brother William, then a Massachusetts state representative, lobbying U.S. House Speaker John McCormack, according to Dick Lehr and Gerard O’Neill, authors of a 2013 biography, “Whitey: The Life of America’s Most Notorious Mob Boss.”

Returning to Boston, Bulger became a leading light in the underworld. According to court testimony, he gave information to Connolly about New England’s entrenched Mafia families. When it came to Bulger’s illicit dealings, Connolly and other agents looked the other way.

“Informants like these come along once in a lifetime,” Connolly told the Washington Post in 1999. “And I’m sorry, they’re never going to be angels. They’re going to be sociopaths.”

Connolly, who accepted a diamond ring, a $10,000 retirement bonus and other gifts from Bulger, said his superiors allowed Bulger and Flemmi to run gambling, loan-sharking and extortion operations without interference. “But not serious violence,” he said. “You know — violence violence.”

In 2002, the retired FBI agent was convicted of racketeering and obstruction of justice for helping Bulger flee. In 2008, he was handed an additional 40-year sentence for giving Bulger information that led to a Florida killing.

At his own trial, Bulger never took the stand. During a jury break, he told U.S. District Judge Denise J. Casper that she had made the proceedings a “sham” by throwing out his main argument: a purported deal with a federal prosecutor that granted him immunity for all crimes past and present in exchange for information that had saved the prosecutor’s life.

The judge declared that such a deal would have been illegal. Besides, she said, there was no evidence of the arrangement Bulger claimed he had struck with U.S. Atty. Jeremiah O’Sullivan, who died in 2009.

As Casper handed down Bulger’s sentence for acts of “almost unfathomable depravity,” she bristled over the admiration he had drawn in the past.

“You have over time and in certain quarters become a face of this city,” the judge told him. “That is regrettable.… You, sir, do not represent this city.”

UPDATES:

4:05 p.m.: The article was updated with additional information about Bulger’s death.

12:35 p.m.: This article was updated with information about the circumstances of Bulger’s death.

This article was originally published at 10:10 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.