Fresh international support for an old U.S. tactic when it comes to Venezuela

Reporting from Washington — The United States has a long history of intervening in Latin America, usually with disastrous consequences and the added burden of alienating other countries.

But the Trump administration’s recognition this week of an opposition leader as president of Venezuela is gathering broad support internationally and on both sides of the U.S. political divide.

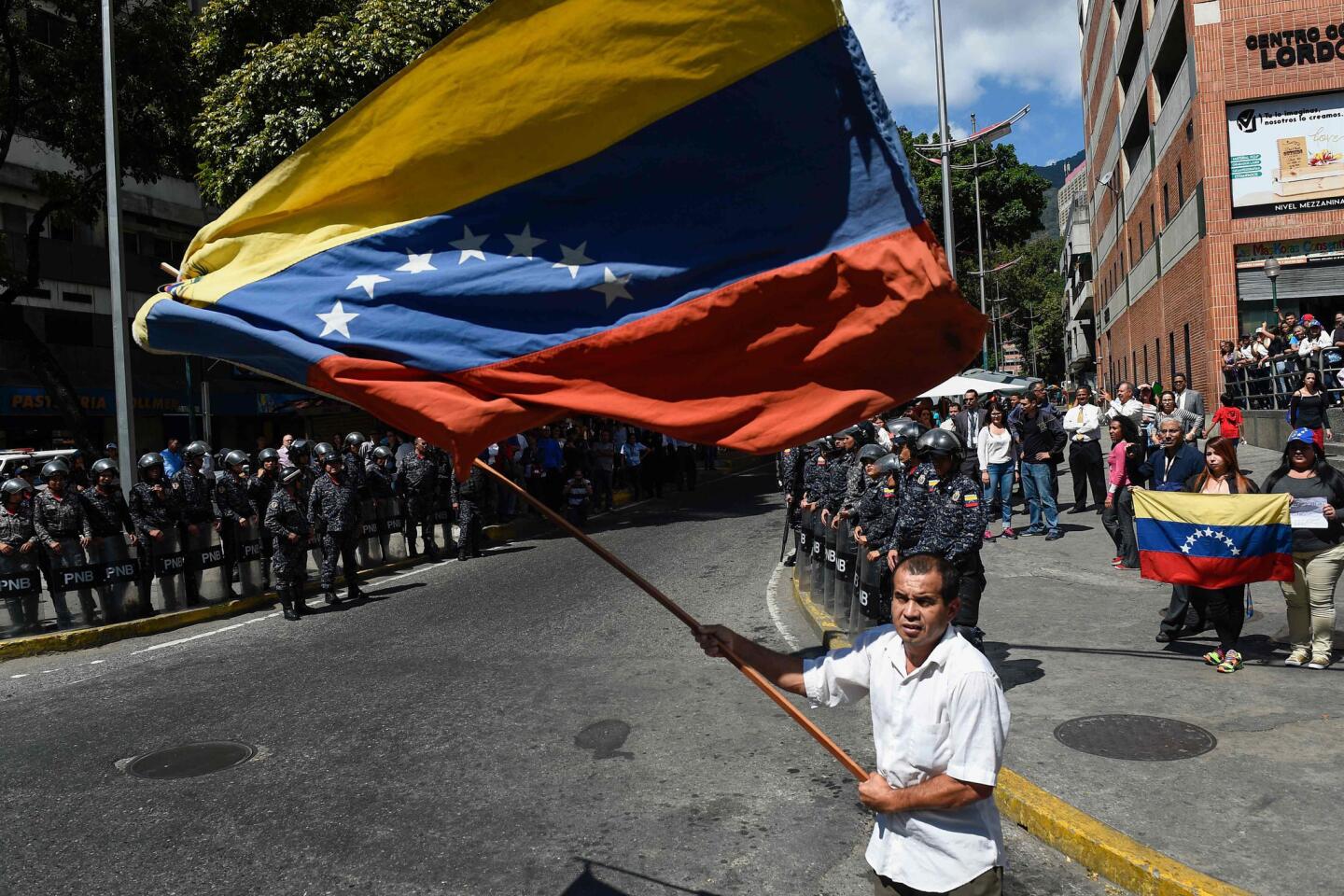

President Trump on Wednesday declared President Nicolas Maduro illegitimate and recognized his main opposition foe, Juan Guaido, as rightful president as tens of thousands of Venezuelans filled streets to protest the Maduro government and the socialist policies that have destroyed the economy.

Trump’s decision was seconded by most of the largest countries in the hemisphere, from Argentina to Canada — but notably not Mexico. Several countries warned of U.S. interventions in the Cold War and before, and accused the United States of attempting to stage a coup d’etat.

The “now-defunct” Maduro regime “is morally bankrupt, criminally incompetent and undemocratic to the core,” Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo told a special session of the Organization of American States in Washington on Thursday.

Pompeo hoped to expand the multilateral coalition dedicated to Maduro’s ouster, but the hemisphere’s principal political body proved sharply divided.

While powerhouses Brazil and Colombia, both led by right-wing governments, and Canada were solidly on board, a half-dozen Caribbean countries called for dialogue and a political solution. They argued that backing Guaido was a violation of international law.

Advocating regime change — or sponsoring it — has long been a feature of U.S. foreign policy in Latin America.

From the 1954 CIA coup in Guatemala that ousted a democratically elected leftist president, to the 1989 U.S. military invasion of Panama to capture Gen. Manuel Noriega, U.S. presidents have toppled strongmen — and installed leaders sympathetic to U.S. priorities — repeatedly over the decades.

So Trump, whose foreign policy is anything but traditional, has followed an old game plan.

Except for his recurring battle with Mexico over immigration, Trump paid little attention to Latin America in his first two years in office.

Venezuela showed up on his radar in large part due to lobbying by Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), who detests leftist governments and went so far as to suggest military intervention to dump Maduro.

In March, John Bolton, another hawk, became Trump’s national security adviser. He pronounced Venezuela, along with Cuba and Nicaragua, a “troika of tyranny” and vowed to isolate and punish them.

The coalition of countries against Maduro has grown in part because several million Venezuelans have fled to neighboring states over the last few years, creating a refugee crisis.

U.S. concerns are more about strategy than human rights, however. Venezuela sits on vast oil reserves yet to be tapped. It also has served as an entry point for Russia, China and Iran to expand influence in the Western hemisphere.

Russia, especially, helped keep Maduro in power by granting him multibillion-dollar loans, investments in oil and gold mining, and arm deals. Last year Russia dispatched a pair of warplanes in what it described as a permanent military presence in the Americas.

As expected, Moscow was most vocal Thursday in condemning Trump’s decision, accusing the president of assuming the “role of the self-proclaimed arbiter of the destinies of other nations.”

“Incitement has nothing to do with the democratic process,” the Russian Foreign Ministry said in a statement. “This is a direct path to lawlessness and bloodshed.”

Mexico was the biggest disappointment to Washington. Its previous government backed the anti-Maduro campaign, but voters last year elected a leftist president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, and he vowed to return Mexico to an inward-looking foreign policy.

“We must conduct foreign policy under the principles of non-intervention, self-determination and peaceful solutions to controversies,” Lopez Obrador told reporters Thursday in Mexico City.

The international community’s attempt to build an alternative government in Venezuela could still turn very ugly.

“The international community means well, but it can’t simply wish a new government into existence,” said Benjamin Gedan, an expert on South America at the nonpartisan Wilson Center think tank in Washington.

Venezuela’s military may yet decide to intervene. The most corrupt generals are likely to stick with Maduro, but lower-level officers and the rank and file who are less involved in corruption might be willing to defect. Guaido has already offered amnesty to army officers.

“The clear regional shift against Maduro has provided energy and political backing to the opposition,” Amanda Lapo, a defense researcher, said for an analysis by the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies. “If it can use this momentum to gain the support of Venezuela’s military, it will have a decisive advantage.”

The Trump administration and the embattled Maduro government were locked in a potentially dangerous showdown Thursday after Maduro ordered U.S. diplomats out of the country by Sunday and Washington refused to comply, saying they would stay put.

Later Thursday, the State Department ordered all “non-emergency” U.S. government employees to leave Venezuela, and urged ordinary U.S. citizens living or traveling in Venezuela to consider leaving.

Maduro cut diplomatic ties with the United States and ordered closed the Venezuelan embassy and all consulates in the United States.

In Caracas, Maduro was drumming up his own support. He lined up institutions that he has filled with his supporters, such as the Supreme Court, to declare their loyalty.

Top military commanders also fell in line, broadcasting a communique pledging allegiance to Maduro. Several of the generals have been blacklisted by the U.S. Treasury Department over allegations of drug trafficking and other crimes.

Maduro appeared at the Supreme Court, bedecked with the yellow, blue and red presidential sash, and vowed to stay in office.

“What is happening in Venezuela is a huge provocation directed by Donald Trump himself who wants to impose a de facto government here, in his craziness of thinking he is the policeman of the world,” Maduro said.

“I’m alive and I will never resign,” he said, adding he had spent 20 minutes talking to Russian President Vladimir Putin on the telephone.

For his part, Guaido spent much of the day tweeting about support he was receiving from the region’s leaders.

“The whole world supports us,” he tweeted.

Wilkinson reported from Washington and special correspondent Mogollon from Caracas. Special correspondent Sabra Ayres reported from Moscow.

For more on international affairs, follow @TracyKWilkinson on Twitter

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.