Egypt’s presidential election looks set to be a one-man affair

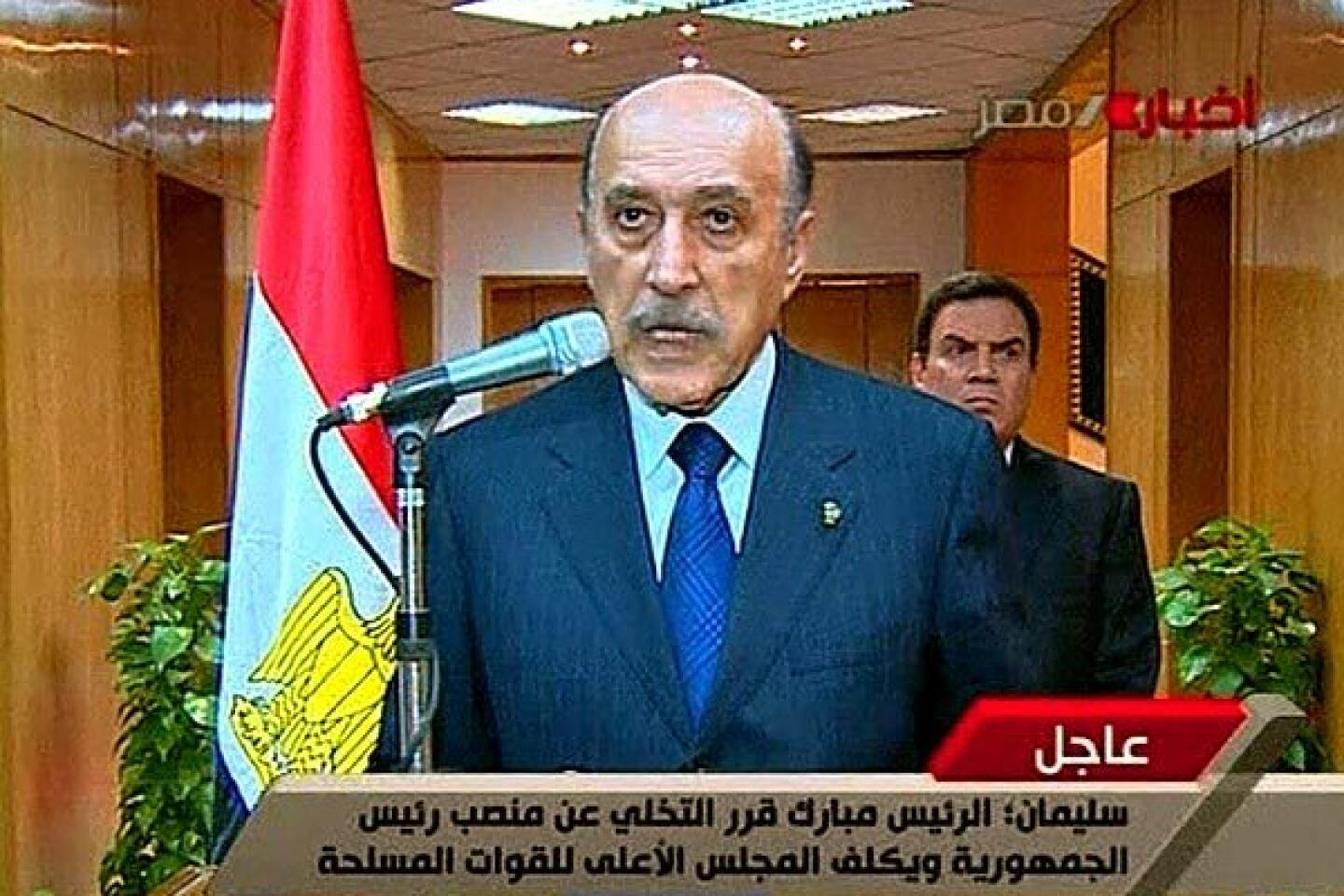

Seven years after massive street protests in Cairo that toppled longtime dictator Hosni Mubarak and galvanized “Arab Spring” revolts across the region, Egypt’s field of hopefuls in its presidential election has essentially dwindled to one: President Abdel Fattah Sisi.

And for supporters of the former field marshal, that’s a bit embarrassing: Even if Sisi scores a near-unanimous victory at the ballot box, as he did in a previous vote, many in his camp would like him to have at least a symbolic opponent. But critics say it is the president’s backers who have engineered a string of abrupt bowings-out by potential rivals.

With the nationwide vote set for late March, Egypt is in familiar territory: furiously denying claims by democracy advocates, and a prominent U.S. senator, that the country has lurched backward into repression that is reminiscent of Mubarak’s three decades of harsh rule.

Those accusations would be bolstered if the vote is little more than a rubber-stamp referendum on the rule of Sisi, 63, who has received little in the way of pushback from the Trump administration over accusations of widespread human rights abuses.

With the last of Sisi’s main rivals having exited — and the president officially in the running — here is a look at Egypt’s upcoming vote and the personalities and issues surrounding it.

What are the requirements for entering the race?

The deadline for candidates to declare and qualify is Monday. Candidates need the stated support of at least 20 lawmakers, or petition signatures from 25,000 eligible voters in 15 governorates, or states. The initial round of voting is set to take place March 26-28, with a second round to be held the following month if no candidate wins a majority.

Who has thought about running, only to drop out?

One of Sisi’s best-known potential challengers was Ahmed Shafiq, a former prime minister, Cabinet minister and air force commander. Living in self-imposed exile in the United Arab Emirates, where he fled after losing a presidential election to Islamist Mohamed Morsi, Shafiq had announced his candidacy in November — only to be detained and deported back to Egypt, where he briefly disappeared. Upon resurfacing, he declared on Twitter that he was “not the ideal person” to try to run the country.

Another hopeful who emerged only to find himself behind bars was Col. Ahmed Konsowa, who threw his hat in the ring back in December, but was arrested soon after and sentenced to six years in prison after trial by a military court. The French news agency Agence-France Presse quoted his lawyer as saying that the sentence was for “political opinions contrary to requirements of public order.”

Did that scare off other potential candidates?

This month, a nephew of assassinated Egyptian President Anwar Sadat said he would not jump into the race as expected, citing an atmosphere of fear and intimidation. Mohamed Anwar Sadat, a former lawmaker, was expelled last year by parliament.

Then last week, Khaled Ali, a prominent human rights lawyer, also decided against entering the race. He had been critical of official roadblocks to formally getting on the ballot, including a suspended jail sentence for what he said were trumped-up charges. At a news conference Wednesday announcing his decision, Ali declared that the “opportunity for hope” in connection with the vote was gone.

Also last week, another contender, former army chief of staff Sami Annan, was detained — a move that drove him out of the race and was seen as evidence Sisi was willing to move even against other members of his own milieu: active or retired members of Egypt’s military establishment.

Critics say not only potential presidential challengers, but their supporters as well, face serious dangers. Annan backer Hesham Geneina, a corruption whistleblower, was physically assaulted last week by unknown assailants, leaving him with broken bones and knife wounds, according to his lawyer.

How has the opposition responded?

Egypt’s political opposition tends to be highly fragmented, but five opposition figures, including Sadat and two of Annan’s former campaign aides, have banded together and called for a boycott of the March vote. In a statement issued Sunday, they said the outcome would not be credible.

Is Egypt bothered by criticism of its electoral process and Sisi’s policies?

It would seem so. Strict laws limit public protests, civil society organizations are under heavy pressure and access to dozens of news websites has been blocked. Egypt’s Foreign Ministry reacted angrily to a statement issued last week by Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.). In it, McCain criticized the human rights crackdown that has taken place under Sisi. The senator pointed to the imprisoning of tens of thousands of dissidents, many of them young people, and said recent years had seen Egypt “lurch dangerously backwards.” The ministry retorted that McCain’s statement included “unfounded accusations” and “fallacies.”

How did Sisi take power?

After a period of upheaval following the revolution that toppled Mubarak, the country held its first democratic elections in 2012, and Morsi was elected. But a year later, he was ousted from office and jailed by Sisi, with the backing of Egypt’s military, and the former military officer then moved ahead with a broad crackdown on Morsi’s movement, the Muslim Brotherhood. In 2014, Sisi garnered nearly 97% of the vote against a lone opponent.

Might someone still make a last-minute run against Sisi after all?

In what could be a face-saving scenario for the president, weekend news reports in Egypt said the Wafd Party, which had stated its support for Sisi, was seeking to put forth its leader, Sayed Badawi, as a candidate. But as of Sunday, the party appeared to be wavering on that plan.

Twitter: @laurakingLAT

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.