Enrique’s Journey | Chapter Three: Defeated Seven Times, a Boy Again Faces ‘the Beast’

Enrique wades chest-deep across a river. He is 5 feet tall, stoop-shouldered and cannot swim. The logo on his cap boasts hollowly, “No Fear.”

The river, the Rio Suchiate, forms the border. Behind him is Guatemala. Ahead is Mexico, with its southernmost state of Chiapas. “Ahora nos enfrentamos a la bestia,” immigrants say when they enter Chiapas. “Now we face the beast.”

Painfully, Enrique, 17, has learned a lot about “the beast.” In Chiapas, bandits will be out to rob him, police will try to shake him down, and street gangs might kill him. But he will take those risks, because he needs to find his mother.

When he was 5 years old, she left him in Honduras and joined hundreds of thousands of women from Central America and Mexico seeking work in the United States. An estimated 48,000 youngsters go north alone every year, many to search for their mothers.

This is Enrique’s eighth attempt to reach El Norte. First, always, comes the beast. About Chiapas, Enrique has discovered several important things.

In Chiapas, do not take buses, which must pass through nine permanent immigration checkpoints. A freight train faces checkpoints as well, but Enrique can jump off as it brakes, and if he runs fast enough, he might sneak around and meet the train on the other side.

In Chiapas, never ride alone.

In Chiapas, do not trust anyone in authority and beware even the ordinary residents, who tend to dislike migrants.

Once the Rio Suchiate is safely behind him, Enrique beds down for the night in a cemetery near the depot in the town of Tapachula, tucking the “No Fear” cap beneath him so it will not be stolen. He is close enough to hear diesel engines growl and horns blare whenever a train pulls out.

The cemetery is a way station for immigrants. At sunup on any given day, it seems as uninhabited as a country graveyard, with crosses and crypts painted periwinkle, neon green and purple. But then, at the first rumble of a departing train, it erupts with life. Dozens of migrants, children among them, emerge from the bushes, from behind the ceiba trees and from among the tombs.

They run on trails between the graves and dash headlong down the slope. A sewage canal, 20 feet wide, separates them from the rails. They jump across seven stones in the canal, from one to another, over a nauseating stream of black. They gather on the other side, shaking the water from their feet. Now they are only yards from the rail bed.

On this day, March 26, 2000, Enrique is among them. He sprints alongside rolling freight cars and focuses on his footing. The roadbed slants down at 45 degrees on both sides. It is scattered with rocks as big as his fist. He cannot maintain his balance and keep up, so he aims his tattered tennis shoes at the railroad ties. Spaced every few feet, the ties have been soaked with creosote, and they are slippery.

Here the locomotives accelerate. Sometimes they reach 25 mph. Enrique knows he must heave himself up onto a car before the train comes to a bridge just beyond the end of the cemetery. He has learned to make his move early, before the train gathers speed.

Most freight cars have two ladders on a side, each next to a set of wheels. Enrique always chooses a ladder at the front. If he misses and his feet land on the rails, he still has an instant to jerk them away before the back wheels arrive.

But if he runs too slowly, the ladder will yank him forward and send him sprawling. Then the front wheels, or the back ones, could take an arm, a leg, perhaps his life.

“Se lo comio el tren,” other immigrants will say. “The train ate him up.”

The lowest rung of the ladder is waist-high. When the train leans away, it is higher. If it banks a curve, the wheels kick up hot white sparks, burning Enrique’s skin.

He has learned that if he considers all of this too long, then he falls behind--and the train passes him by.

This time, he trots alongside a gray hopper car. He grabs one of its ladders, summons all of his strength and pulls himself up. One foot finds the bottom rung. Then the other.

He is aboard.

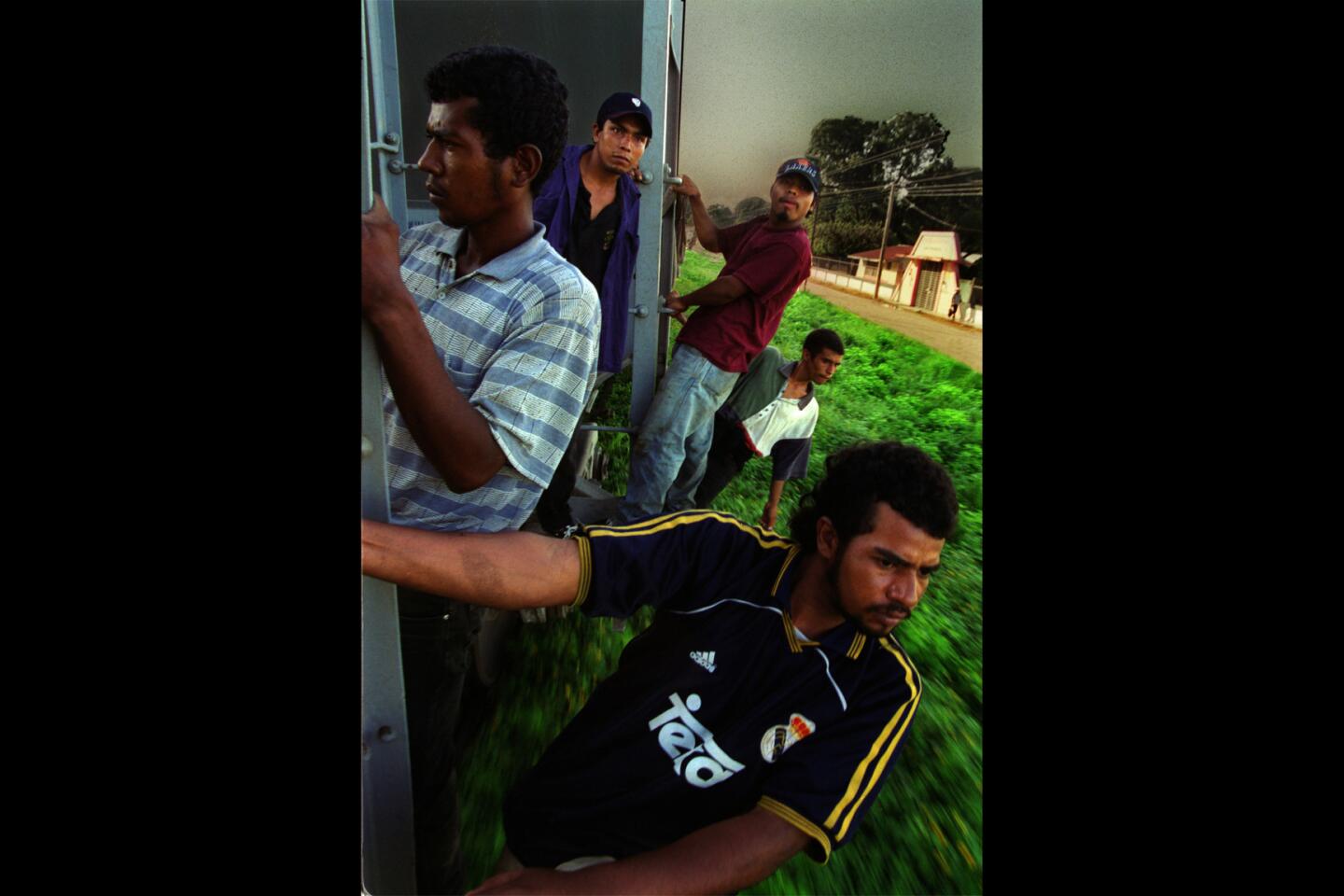

Enrique looks ahead on the train. Men and boys are hanging on to the sides of tank cars, trying to find a spot to sit or stand. Some of the youngsters could not land their feet on the ladders and have pulled themselves up rung by rung on their knees, which are bruised and bloodied.

Suddenly, Enrique hears screams.

Three cars away, a boy, 12 or 13 years old, has managed to grab the bottom rung of a ladder on a fuel tanker, but he cannot haul himself up. Air rushing beneath the train is sucking his legs under the car. It is tugging at him harder, drawing his feet toward the wheels.

“Don’t let go!” a man shouts. He and others crawl along the top of the train to a nearby car. They shout again.

The boy dangles from the ladder. He struggles to keep his grip.

Carefully, the men crawl down and reach for him. Slowly, they lift him up. The rungs batter his legs, but he is alive. He still has his feet.

::

Getting aboard

Enrique guesses there are more than 200 migrants on board, a tiny army of them who charged out of the cemetery with nothing but their cunning.

Arrayed against them are Mexican immigration authorities, or la migra, along with crooked police, street gangsters and bandits. They wage what a priest at an immigrant shelter calls “la guerra sin nombre,” the war with no name. Chiapas, he says, “is a cemetery with no crosses, where people die without even getting a prayer.”

All of this is nothing, however, against Enrique’s longing for his mother, who left him behind 11 years ago. Although his effort to survive often forces her out of his mind, at times he thinks of her with a loneliness that is overwhelming. He remembers when she would call Honduras from the United States, the concern in her voice, how she would not hang up before saying: “I love you. I miss you.”

Enrique considers carefully. Which freight car will he ride on? This time he will be more cautious than before.

Boxcars are the tallest. Their ladders do not go all the way up. Migra agents would be less likely to climb to the top. And he could lie flat on the roof and hide. From there, he could see the agents approaching, and if they started to climb up, he could jump to another car and run.

But boxcars are dangerous. They have little on top to hold on to.

Inside a boxcar might be better.

But police, railroad security agents or la migra could bar the doors, trapping him inside. If the doors closed accidentally, he might die. Migrants say temperatures inside climb to 100 degrees, and people kneel to ask God to stop the train. Some suffocate, and others stand on their bodies to reach tiny air holes above the doors.

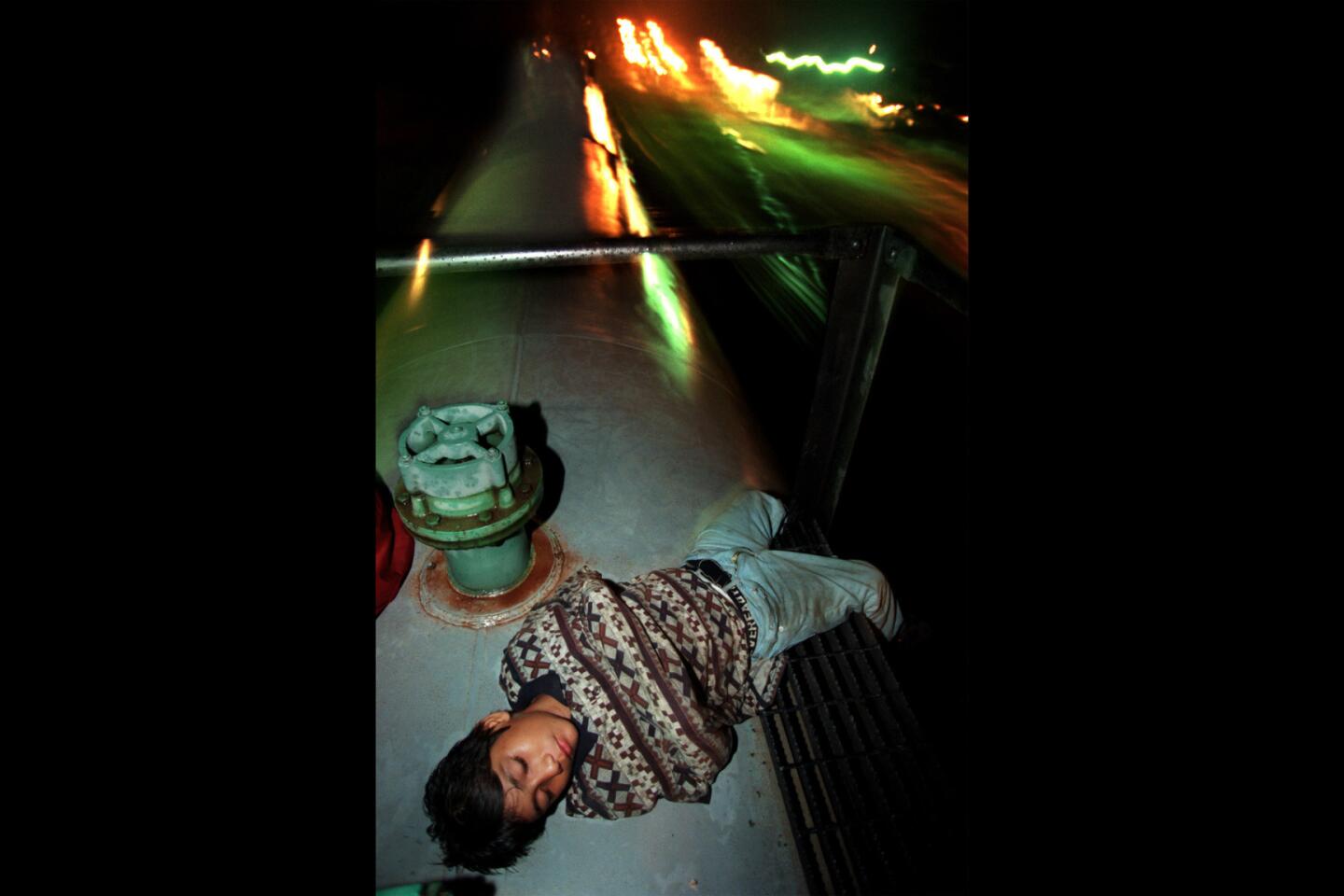

A good place to hide could be under the cars, up between the axles, balancing on a foot-wide iron shock absorber. But Enrique might be too big to fit. Besides, trains kick up rocks. Worse, if his arms grew tired, or if he fell asleep, he would drop directly under the wheels.

Enrique settles for the top of a hopper. He holds on to a grate running along the rim. From his perch 14 feet up, he can see anyone approaching on either side of the tracks, up ahead or from another car. Below, at each end, the hopper’s wheels are exposed: shiny metal, 3 feet in diameter, 5 inches thick, churning. He stays as far away as he can.

He doesn’t carry anything that might keep him from running fast. At most, if it is exceptionally hot, he ties a nylon string on an empty plastic bottle, wraps it around his arm and fills the bottle with water when he can.

Some immigrants climb on board with a toothbrush tucked into a pocket. Others bring a small Bible with telephone numbers, penciled in the margins, of their mothers or fathers or other relatives in the United States. Maybe nail clippers, a rosary or a scapular with a tiny drawing of San Cristobal, the patron saint of travelers, or of San Judas Tadeo, the patron saint of desperate situations.

As usual, the train lurches hard from side to side. Enrique holds on with both hands. Occasionally, the train speeds up or slows down, smashing couplers together and jarring him backward or forward. The wheels rumble. Sometimes each car rocks the other way from the ones ahead and behind. El Gusano de Hierro, some migrants call it. The Iron Worm.

In Chiapas, the tracks are 20 years old. Some of the ties sink, especially during the rainy season, when the roadbed turns soggy and soft. Grass grows over the rails, making them slippery.

When the cars round a bend, they feel as if they might overturn. Enrique’s train runs only a few times a week, but it averages three derailments a month, by the count of Jorge Reinoso, chief of operations for Ferrocarriles Chiapas-Mayab, the railroad. One year before, a hopper like Enrique’s overturned with a load of sand, burying three immigrants alive. Enrique rarely lets himself admit fear, but he is scared that his car might tip. El Tren de la Muerte, some migrants call it. The Train of Death.

Enrique is struck by the magic of the train--its power and its ability to take him to his mother. To him, it is El Caballo de Hierro. The Iron Horse.

The train picks up speed. It passes a brown river that smells of sewage. Then a dark form emerges ahead. “Rama!” the immigrants yell. “Branch!” They duck.

Enrique grips the hopper. To avoid the branches, he sways from side to side. All of the riders sway in unison, ducking the same branches--left then right. One moment of carelessness and the branches will hurl them into the air. Matilda de la Rosa, who lives by the tracks, recalls a migrant who came to her door with an eyeball hanging on his cheek. He cupped it near his face, in his right hand. He told her, “The train ripped out my eye.”

::

A dreaded stop

Each time the train slows, Enrique goes on high alert for la migra.

Immigrants wake one another and begin climbing down to prepare to jump. If the train speeds up again, everyone climbs back up. The movement down and up the ladders looks like a strangely choreographed two-step.

But slowing down at Huixtla, with its red and yellow depot, can mean only one thing: Coming up is La Arrocera, one of the most dreaded immigration checkpoints in Mexico.

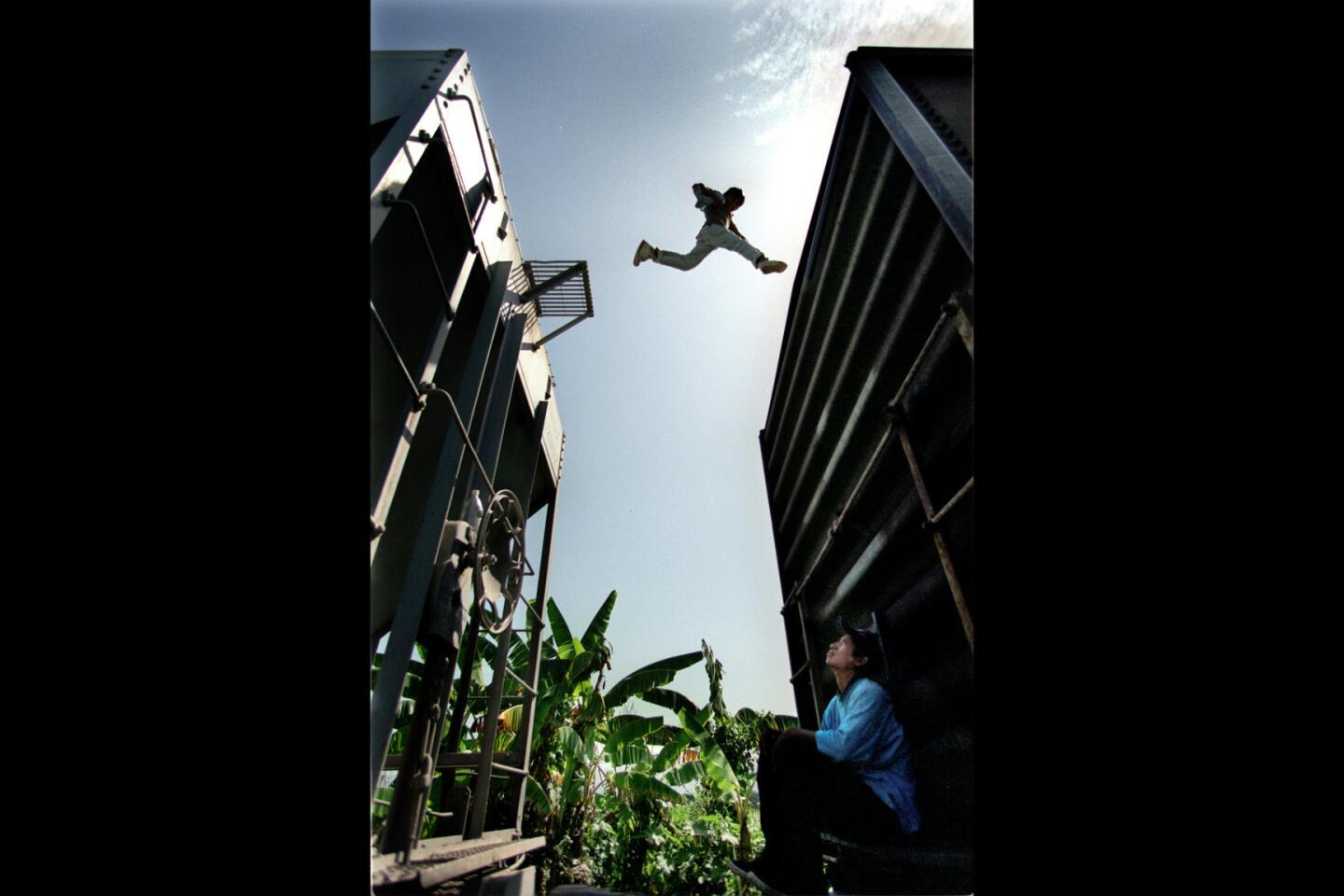

Enrique has defied La Arrocera before. This time, he arrives in the heat of noon. Tension builds. Some migrants stand on top of the train, straining to see the migra agents up ahead. As the train brakes, they jump.

The train lurches sideways. Enrique leaps from car to car, finally landing on a boxcar. The train stops. He lies flat, face down, arms spread-eagle, hoping la migra won’t see him. But several agents do.

“Bajate, puto! Get down, you whore!”

“No! I’m not coming down!”

There is no ladder all the way to the top. Maybe they won’t come up after him.

“Get down!”

“No!”

The agents summon reinforcements. One starts to climb up.

Enrique scrambles to his feet and races along the top of the train, soaring across the 4-foot gaps between cars. As he runs, three agents follow on the ground, pelting him with rocks and sticks, an experience many immigrants say they have here. Stones clang against the metal. Enrique flees from car to car, more than 20 in all, struggling to keep his footing each time he leaps from a hopper to a fuel tanker, which is lower and has a rounded top.

He is running out of train. He will have to go around La Arrocera alone. It may be suicidal, but he has no choice. More stones ping off the train. Enrique scurries down a ladder and sprints into the bushes.

“Alto! Alto! Stop!” the agents shout.

As Enrique runs, he hears what he thinks are gunshots behind him.

Except in extraordinary circumstances, Mexican immigration agents are barred from carrying firearms. According to a retired agent, however, most have .38-caliber pistols. Some of the shelter workers tell of migrants hit by bullets. Others tell of torture. Before long, Enrique will meet a man whose chest is pockmarked with cigarette burns. The man tells him that a migra agent at La Arrocera branded him.

In the scrub brush, though, Enrique worries less about agents than about madrinas with machetes. The name for these men is a play on words: These civilians help the authorities, as a madrina, or godmother, would, and administer madrizas, or savage beatings. Human rights activists and some police agencies say the madrinas commit some of the worst atrocities--rapes and torture--and are allowed by authorities to keep a portion of what they steal.

Enrique runs on. He crawls under a barbed wire fence, then under a double strand of smooth wire. It is electrified. At night, Guillermina Galvez Lopez, who lives at La Arrocera, hears the trains and, not long afterward, the piercing screams of immigrants, wet from the swampy grass, who run into the wire.

“Help me! Help me!” they wail.

Ten times in 10 months, train riders have carried to her front door men and boys without arms, legs or heads. In 1999, Clemente Delporte Gomez, a patrolman with Grupo Beta Sur, the government’s migrant rights organization, watched a young Salvadoran slip on railroad ties near La Arrocera. Train wheels cut him in two at the midriff. Delporte saw the Salvadoran’s heart flicker three times. Then it was still.

Enrique knows he has plunged deep into bandit territory. At least three, maybe five swarms of robbers, some with Uzis, some on drugs, patrol the three-mile dirt paths that immigrants must use to go around La Arrocera, authorities say. They seem to operate with such impunity that Mario Campos Gutierrez, a supervisor with Grupo Beta, thinks the authorities collaborate.

Before taking these paths, migrants hide their money. Some stitch it into the seams of their pants. Others put a bit in their shoes, a bit in their shirts and a coin or two in their mouths. Still others bag it in plastic and tuck it into intimate places. Some roll it up and slip it into their walking sticks. Others hollow out mangoes, drop their pesos inside, then pretend to be eating the fruit.

Enrique figures he doesn’t have enough money to bother.

Last time he sneaked past La Arrocera, he was lucky because he was careful. He stuck with a band of street gangsters. This time he is alone. He focuses on the thought that will make him run the fastest: “I cannot miss the train.”

If he misses the one he just left, he knows he will be a sitting duck, waiting for days in the bushes and the tall grass until another one comes.

Enrique races so fast he feels the blood pounding at his temples. The grass, growing in three-foot tentacles, lassos his feet. He stumbles, gets up and keeps running. He passes an abandoned brick house. Half the roof is gone.

The house is notorious. Not long before, Grupo Beta had found a bed of bricks inside, covered with emerald green leaves from a plant that looked like a bird of paradise--and two soiled pairs of panties crumpled on the dirt floor. Women are raped here, most recently a 16-year-old assaulted repeatedly over three days.

Many are gang-raped, including a Salvadoran woman, four months pregnant, who was assaulted at gunpoint by 13 bandits along the railroad tracks to the south. Nearly one in six immigrant girls detained by authorities in Texas says she has been sexually assaulted during her journey, according to a 1997 University of Houston study. Some girls journeying north cut off their hair, strap their breasts and try to pass for boys. Others scrawl on their chests: “TENGO SIDA. I have AIDS.”

Enrique does not stop. He reaches the Cuil bridge, where the railroad spans a 40-foot stream of murky brown water. This, migrants and Grupo Beta officers say, is the most dangerous spot. Bandits haul mattresses up into nearby trees, eat lunch and wait for their prey. As immigrants cross the bridge, the bandits drop out of the limbs and surround them. Other robbers hide along the tracks above and below the bridge, which is thick with bushes and vines. One fishes in the river or cuts grass with a machete, like a fieldworker, and whistles to the others to set a trap.

Just a month before, bandits ambushed five Salvadorans as they crossed the bridge at 4 a.m. They tried to run. The bandits shot one in the back. Four months later, three Salvadorans and a Mexican, all in their 20s, were killed. The Salvadorans, their hands tied behind them, were shot in the head. The Mexican was stabbed. All they had left was their underwear.

Enrique dashes across the bridge and keeps running. Mountains stand to his right. The ground is so wet that farmers grow rice between their rows of corn. He can feel heat and humidity rising from the loamy earth. It saps his energy, but he runs on.

Finally, he stops, doubled over, panting.

He is not sure why, but he has survived La Arrocera. Maybe it was his extra caution, maybe it was his decision to run, maybe it was his attempt to lie flat and hide atop the boxcar, which delayed his getting off the train and gave the bandits an opportunity to target migrants ahead of him.

He is desperate for water. He spots a house.

The people inside are not likely to give him any. Chiapas is fed up with Central American immigrants, says Hugo Angeles Cruz, a professor and migration expert at El Colegio de la Frontera Sur in Tapachula. They are poorer than Mexicans, and they are seen as backward and ignorant. People think they bring disease, prostitution and crime and take away jobs. Some cannot be trusted. People in Chiapas talk of being robbed by migrants with guns and knives. They tell of an older woman who welcomed an immigrant into her home and was beaten to death with an iron pipe.

Boys like Enrique are called “stinking undocumented.” They are cursed, taunted. Dogs are set upon them. Barefoot children throw rocks at them. Some use slingshots. “Go to work.” “Get out! Get out!”

Drinking water can be impossible to come by. Migrants filter ditch sewage through T-shirts. Finding food can be just as difficult. Enrique is counting: In some places, people at seven of every 10 houses turn him away.

“No,” they say. “We haven’t cooked today. We don’t have any tortillas. Try somewhere else.”

“No, boy, we don’t have anything here.”

Sometimes it is worse. People in the houses turn the immigrants in.

Enrique sees another migrant who has managed to make it around La Arrocera. He, too, needs water badly, but he doesn’t dare ask. He is afraid of walking into a trap. To immigrants, begging in Chiapas is like walking up to a loaded gun.

“I’ll go,” Enrique says. “If they catch someone, it will be me.”

He approaches a house and speaks softly, his head slightly bowed. “I’m hungry. Can you spare a taco? Some water?” The woman inside sees injuries from the train-top beating he took during his last attempt to go north. “What happened?” she asks. She gives him water, bread and beans.

The other migrant comes nearer. She gives him food too.

A horn blows. Enrique runs to the tracks. Other immigrants who have survived La Arrocera come out of the bushes. They sprint alongside the train and reach for the ladders on the freight cars.

Enrique climbs up onto a hopper. The train picks up speed.

For the moment, he relaxes.

::

Staying awake

The Iron Worm squeaks, groans and clanks--black tankers, rust-colored boxcars and gray hoppers winding north on a single track that parallels the Pacific coast. Off to the right are hillsides covered with coffee plants. Cornstalks grow up against the rails. The train moves through a sea of plantain trees, lush and tropical.

By early afternoon, it is 105 degrees. Enrique’s palms burn when he holds on to the hopper. He risks riding no-hands. Finally, he strips off his shirt and sits on it. The locomotive blows warm diesel smoke. People burn trash by the rails, sending up more heat and a searing stench. Enrique’s head throbs. The sun stings in his eyes, and his skin tingles. He moves around the car, chasing patches of shade. For a while, he stands on a narrow ledge at the end of a fuel tanker. It is just inches above the wheels.

He cannot let himself fall asleep; one good shake of the train, and he would tumble off.

Moreover, street gangsters, some deported from Los Angeles, prowl the train tops looking for sleepers. Many of the migrants huddle together, hoping for safety in numbers. They watch for anyone with tattoos, especially gangsters who have skulls inked around their ankles--one skull, police say, for every person they have killed. Their brutality is legendary. Immigrants tell of nine gangsters who hurled a man off their train, then forced two boys to have sex together or be thrown off too.

Some migrants nap on their feet, using belts or shirts to strap themselves to posts at the ends of the hoppers. Others struggle to stay awake. They take amphetamines, slap their own faces, do squats, talk to one another and sing. At 4 a.m. the train sounds like a chorus.

Today, Enrique is terrified of another beating. Every time someone new jumps onto his car, he tenses. Fear, he realizes, helps to keep him awake, so he decides to induce it. He climbs to the top of the tank car and takes a running leap. With arms spread, as if he were flying, he jumps to one swaying boxcar, then to another. Some have 4-to-5-foot gaps. Others are 9 feet apart.

The train passes into northern Chiapas. Mountains draw closer. Plantain fields soften into cow pastures. Enrique’s train slows to a crawl. As the sun sets, he hears crickets begin their music and join the immigrant chorus.

The train nears San Ramon, close to the northern state line. It is past midnight now, and the judicial police are probably asleep. Train crews say this is where the police stage their biggest shakedowns. One conductor says the officers, 15 at a time, stop the trains. They grab fleeing migrants by their shirts. The conductor has heard them say: “If you move, I’ll kill you. I’ll break you in two.” Then, “Give us what you’ve got, or we send you back.”

At nearby Arriaga, the chief of the judicial police, or Agencia Federal de Investigacion, denies that his agents stop trains in San Ramon and rob immigrants. The chief, Sixto Juarez, suggests that any robbing is done by gangsters or bandits who impersonate judicial officers.

Enrique greets the dawn without incident. He puts Chiapas behind him. He still has far to go, but he has faced the beast eight times now, and he has lived through it.

It is an achievement, and he is proud of it.

::

Acting Oaxacan

Around noon, he reaches Ixtepec, a southern crossroads in Oaxaca, the next state north, 285 miles into Mexico. As his train squeals to a stop, migrants jump down and look for houses where they can beg for a drink and a bite to eat. La bestia might be behind them, but most are still afraid. Two of them are too frightened to go into town. They offer Enrique 20 pesos and ask him to buy food. If he will bring it back, they will share it with him.

He takes off his yellow shirt, stained and smelling of diesel smoke. Underneath he wears a white one. He puts it on over the dirty one. Maybe he can pass for someone who lives here. He resolves not to panic if he sees a policeman, and to walk as if he knows where he is going.

He takes the pesos and walks down the main street, past a bar, a store, a bank and a pharmacy. He stops at a barber shop. His hair is curly and far too long. It is an easy tip-off. People here tend to have straighter hair.

He strides purposefully inside.

“Orale, jefe!” he says, using a phrase Oaxacans favor. “Hey, chief!” He mutes his flat, Central American accent and speaks softly and singsongy, like a Oaxacan. He asks for a short crop, military style. He pays with the last of his own money, careful not to call it pisto, as they do back home. That means alcohol up here.

He is mindful about what else he says. Migra agents trip people up by asking if the Mexican flag has five stars (the Honduran flag has, but the Mexican flag has none), or by demanding the name of the mortar used to make salsa (molcajete, a uniquely Mexican word), or inquiring how much someone weighs. If he replies in pounds, he is from Central America. In Mexico, people use kilos.

In Guatemala, soda is called agua. Here in Mexico, agua is water. A jacket is a chamarra, not a chumpa. A T-shirt is a playera, not a blusa.

At one point, Enrique glances into a store window and sees his reflection. It is the first time he has looked at his face since he was beaten. He recoils from what he sees. Scars and bruises. Black and blue. One eyelid droops.

It stops him.

He was 5 years old when his mother left him. Now he is almost another person. In the window glass, he sees a battered young man, scrawny and disfigured.

It angers him, and it steels his determination to push northward.

Next: Chapter Four: Inspired by Faith, the Poor Rush Forth to Offer Food

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.