Enrique’s Journey | Chapter Five: A Milky Green River Between Him and His Dream

“You are in American territory,” a Border Patrol agent shouts into a bullhorn. “Turn back.”

Sometimes Enrique strips and wades into the Rio Grande to cool off. But the bullhorn always stops him. He goes back.

“Thank you for returning to your country.”

He is stymied. For days, Enrique, 17, has been stuck in Nuevo Laredo, on the southern bank of the Rio Bravo, as it is called here. He has been watching, listening and trying to plan. Somewhere across this milky green ribbon of water is his mother.

She left him behind 11 years ago in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, to seek work in the United States. Enrique is challenging the unknown to find her. During her most recent telephone call, she said she was in North Carolina. He has no idea if she is still there, where that is or how to reach it. He no longer has her phone number.

He had written it on a scrap of paper, but it blew away while he was being robbed and beaten almost four weeks ago while riding on top of a freight train in southern Mexico. He did not think to memorize it.

Of the estimated 48,000 youngsters from Central America and Mexico who go north illegally on their own every year, many do not memorize telephone numbers or addresses. They wrap them in plastic and tuck them into a shoe or slip them under a waistband. Some of the numbers are lost, others are stolen. Occasionally kidnappers snatch the children themselves, find the numbers and call the mothers for ransom.

Stripped of phone numbers and destinations, many of the children become stranded at the river. Defeat drives them to the worst this border world has to offer: drugs, despair and death.

It is almost May 2000, nearly two months since Enrique left home the last time. He is a hardened veteran of seven attempts to reach El Norte. This is his eighth. By now, his mother must have called Honduras again, and the family must have told her that he was gone. His mother must be worrying.

He has to telephone her.

Besides, she might have saved enough money to hire a smuggler, or coyote, who can take him across the river.

He remembers one number back home--at a tire store where he worked. He will call and ask his old employer to find Aunt Rosa Amalia or Uncle Carlos Orlando Turcios Ramos, who had arranged his job, and ask them for his mother’s number. Then he will call back and get it from his boss.

For the two calls, he needs two telephone cards: Fifty pesos apiece. When he phones his mother, he’ll call collect.

He cannot beg 100 pesos. People in Nuevo Laredo won’t give. Mexicans along the border, he notices, are quick to proclaim their right to immigrate to the United States. “Jesus was an immigrant,” he hears them say. But most won’t give Central Americans food, money or jobs.

So he will work by himself. He’ll wash cars.

::

A refuge

The encampment he has joined is a haven for migrants, coyotes, junkies and criminals, but it is safer for him than anywhere else in Nuevo Laredo, a city of half a million and swarming with immigration agents, or la migra, and all kinds of police, who might catch him and deport him.

The camp is at the bottom of a narrow, winding path that slopes to the river. Each evening, without fail, he summons his courage and goes to the Nuevo Laredo city hall with a large plastic paint bucket and two rags. From a spigot on the side of the building, he fills the bucket. Then he goes to parking places across the street from a bustling taco stand. One of his rags is red. Each time someone arrives to eat dinner, he waves the red rag to guide the customer into a parking space, like a ground crew ushering a jetliner to a gate.

Usually there is competition. Two or three others immigrants set up their buckets along the same sidewalk.

Enrique approaches a woman driving a yellow Chevrolet Impala with chrome-spoke wheels. She is talking on her cell phone. May he wash her car?

She ends the call and declines.

A man and his young daughter drive up.

“May I clean your car?”

“No, son.”

The woman with the Impala returns with her tacos. Enrique waits until traffic is clear, then waves his red rag and guides her out.

Suddenly, she reaches out her car window and presses 3 pesos into his hand.

Enrique approaches dozens of people, but just one or two say yes. By 4 a.m., when the stand closes, he has eked out 30 pesos, or $3.

::

A lifeline

The air around the taco stand fills with the aroma of barbecue. Enrique watches workers pull strips of meat from a vat, put them on large chopping blocks and cut them up. Customers sit at long stainless steel tables and eat. Sometimes, when the stand closes, the servers slip him a couple of tacos.

Otherwise, for his only meal every day, he depends upon Parroquia de San Jose, or St. Joseph’s Parish, and another church, Parroquia del Santo Nino, the Parish of the Holy Child. Each gives food cards to migrants. One is good for 10 meals and the other for five. Enrique can count on one meal a day for 15 days. The cards are like gold. Sometimes they are stolen and turn up on a meal-card black market.

Each day, Enrique goes to one church or the other to eat. It is safe; the police stay away. Like clockwork, Leti Limon, a volunteer, swings open the double yellow doors at San Jose and shouts, “Who’s new?”

“Me! Me!” men and boys cry out from the courtyard.

They rush to the door and jostle against it.

“Get in line! Get in line!” Limon is poor herself; she cleans houses across the river in Laredo, Texas, for $20 apiece. But she has helped to feed these immigrants for a year and a half, figuring that Jesus would approve. She issues the newcomers beige cards and punches the cards of those who enter. A parish priest counts 6% children.

One by one, the migrants stand behind chairs at a long table. At the head is a mural of Jesus, his hands extended toward plates of tacos, tomatoes and beans. Above him are his words: “Come to me, all you who are weary and find life burdensome.”

The lights dim, and two big fans spin to a stop, so everyone can hear grace. Some who have not eaten in two or three days cannot wait; from behind their chairs, they grab at the tacos with one hand, bread with the other.

Chairs screech as everyone pulls them out at once. Spoons of stew touch lips before bottoms hit the seats. In a clatter of forks against plates, beans, stew, tomatoes, rice and doughnuts disappear.

::

A smuggler

For permission to stay in the relative safety of the encampment, the leader, El Tirindaro, who is addicted to heroin, usually wants drugs or beer. But he has not asked Enrique for anything. El Tirindaro is a subspecies of coyote known as a patero, because he smuggles people into the United States by pushing them across the river on inner tubes while paddling like a pato, or duck. Enrique is a likely client.

In addition to smuggling, El Tirindaro finances his heroin habit by tattooing people and selling clothing that immigrants have left on the riverbank. Enrique stares as El Tirindaro lies on a mattress, mixes Mexican black tar heroin with water in a spoon, warms it over a cigarette lighter, draws it into a syringe and stabs the needle straight into a vein.

Besides migrants, the camp has 10 perpetual residents. Seven are addicts. They call heroin la cura, or the cure.

Also among the permanent campers are several immigrants who are stuck. One, a fellow Honduran, has lived on the river for seven months. He tried to enter the United States three times. Every time, he was caught. He has descended into depression and a life of glue sniffing.

Each time he tried to cross, he says, he went alone.

Enrique listens. They call him El Hongo, the mushroom, because he is quiet, soaking everything in.

Enrique is protected. Because he is so young, everyone at the camp looks after him. When he goes at night to wash cars, someone walks him through the brush to the road. They warn him against heroin. But leaving the camp scares him, and they give him marijuana to calm him down.

Car washing goes poorly. One night, he earns almost nothing.

The 15 days on his meal cards pass quickly. Now he needs part of his money to eat. Every peso he spends on food cannot go toward the phone cards. He begins to eat as little as possible--crackers and soda.

Sometimes Enrique does not eat at all. Friends at the camp share their meals. One teaches him to fish with a line coiled on a shampoo bottle. The line, fitted with a hook, has three spark plugs at the end to sink it. Enrique swings the spark plugs around his head, then casts toward the middle of the Rio Grande. The line whirs as it spools off the bottle. He hauls in three catfish.

Even El Tirindaro is generous; the sooner Enrique can buy a phone card and call his mother, the sooner Enrique will need his services. When one of Enrique’s meal cards is stolen, El Tirindaro gives him the unexpired card of a migrant who has crossed the river successfully. He knows that Enrique cannot swim, so he paddles him back and forth on the water in an inner tube to quiet his fears.

Enrique learns that El Tirindaro is part of a smuggling network. A middle-aged man and a young woman, both Latinos, meet him and his clients after they cross the river. Then they all drive north together, and El Tirindaro walks his clients around Border Patrol checkpoints, giving wide berth to the agents. After the last checkpoint, El Tirindaro returns to Nuevo Laredo, and the couple and others in the network deliver the clients to their destinations. The price is $1,200.

El Hongo listens as his camp mates talk about dos and don’ts: Find an inner tube. Take along a gallon of water. Learn where to get into the river, where not. They talk about the poverty they came from; they would rather die than go back. Enrique tells them about Maria Isabel, his girlfriend, and that she might be expecting.

Enrique talks about his mother. He says he is extremely depressed.

“I want to be with her,” he says, “to know her.”

“If you talk, it’s better,” a friend says.

But it gets worse. Enrique defends a friend against a street gangster and is spared a beating only by the intervention of another gangster from his neighborhood back home. Then his luck runs out with the authorities. He is arrested in town--twice, both times for loitering. Police call him a street bum and lock him up. In jail, the toilet runs over, and drunks smear the wall with its contents. Both times, Enrique wins his release by sweeping and mopping.

One night, as he walks 20 blocks back to the river from washing cars, it rains. He ducks into an abandoned house, finds some cardboard and places it on a dry spot. He removes his sneakers and puts them and his bucket near his head. He has no socks, blanket or pillow. He pulls his shirt up around his ears and breathes into it to stay warm. Then he lies down, curls up and tucks his hands across his chest.

Lightning flashes. Thunder rumbles. Wind wails around the corners of the house. The rain falls steadily. On the highway, trucks hiss their brakes, stopping at the border before entering the United States. Across the river, the Border Patrol shines lights on the water, looking for immigrants trying to cross.

With his bare feet touching a cold wall, Enrique sleeps.

::

Mother’s Day

It is May 14, 2000, a Sunday when many churches in Mexico celebrate Mother’s Day.

Finally, Enrique has saved 50 pesos. Eagerly, he buys a phone card. He gives it to one of El Tirindaro’s friends for safekeeping. That way, if the police catch him again, they cannot steal it.

“I just need one more,” he says. “Then I can call her.”

Every time he goes to Parroquia de San Jose, it makes him think about his mother, especially on this Mother’s Day. In addition to the refectory, on the second floor are two small rooms where up to 10 women share four beds. They have left their children behind in Central America and Mexico to find work in El Norte, and they have found this place to sleep. Each could be his mother 11 years ago.

They try to ignore a Mother’s Day party downstairs, where 150 women from Nuevo Laredo laugh, shout and whistle as their sons dance, pillows stuffed under their shirts to make them look pregnant. Upstairs, the women weep. One has a daughter, 8, who had begged her not to go. She asked her to send back just one thing for her birthday: a doll that cries. Another cannot shake a nightmare: Back home, her little girl is killed, and her little boy runs away in tears. Daily she prays: “Don’t let me die on this trip. If I die, they will live on the street.”

Enrique wonders: What does his mother look like now?

“It’s OK for a mother to leave,” he tells a friend, “but just for two or four years, not longer.” He recalls her promises to return for Christmas and how she never did. “I’ve felt alone all my life.” One thing, though: She always told him she loved him. “I don’t know what it will be like to see her. She will be happy. Me too. I want to tell her how much I love her. I will tell her I need her.”

Across the Rio Grande on Mother’s Day, his mother, Lourdes, thinks about Enrique. She has, indeed, learned that he is gone. But in her phone calls home, she never finds out where he went. She tries to convince herself that he is living with a friend, but she remembers their last telephone conversation: “I’ll be there soon,” he had said. “Before you know it, on your doorstep.” Day after day, she waits for him to call. Night after night, she cannot sleep more than three hours. She watches TV: migrants dying in the desert, ranchers who shoot them.

She imagines the worst and becomes terrified that she might never see him again. She is utterly helpless. She asks God to watch over him, guide him.

On the afternoon of the Mother’s Day celebration, three municipal police visit the camp. Enrique does not try to run, but he is jittery. They ignore him. Instead, they take away one of his friends.

Enrique has no money for food. He takes a hit of glue. It makes him sleepy, takes him to another world, eases his hunger and helps him forget about his family.

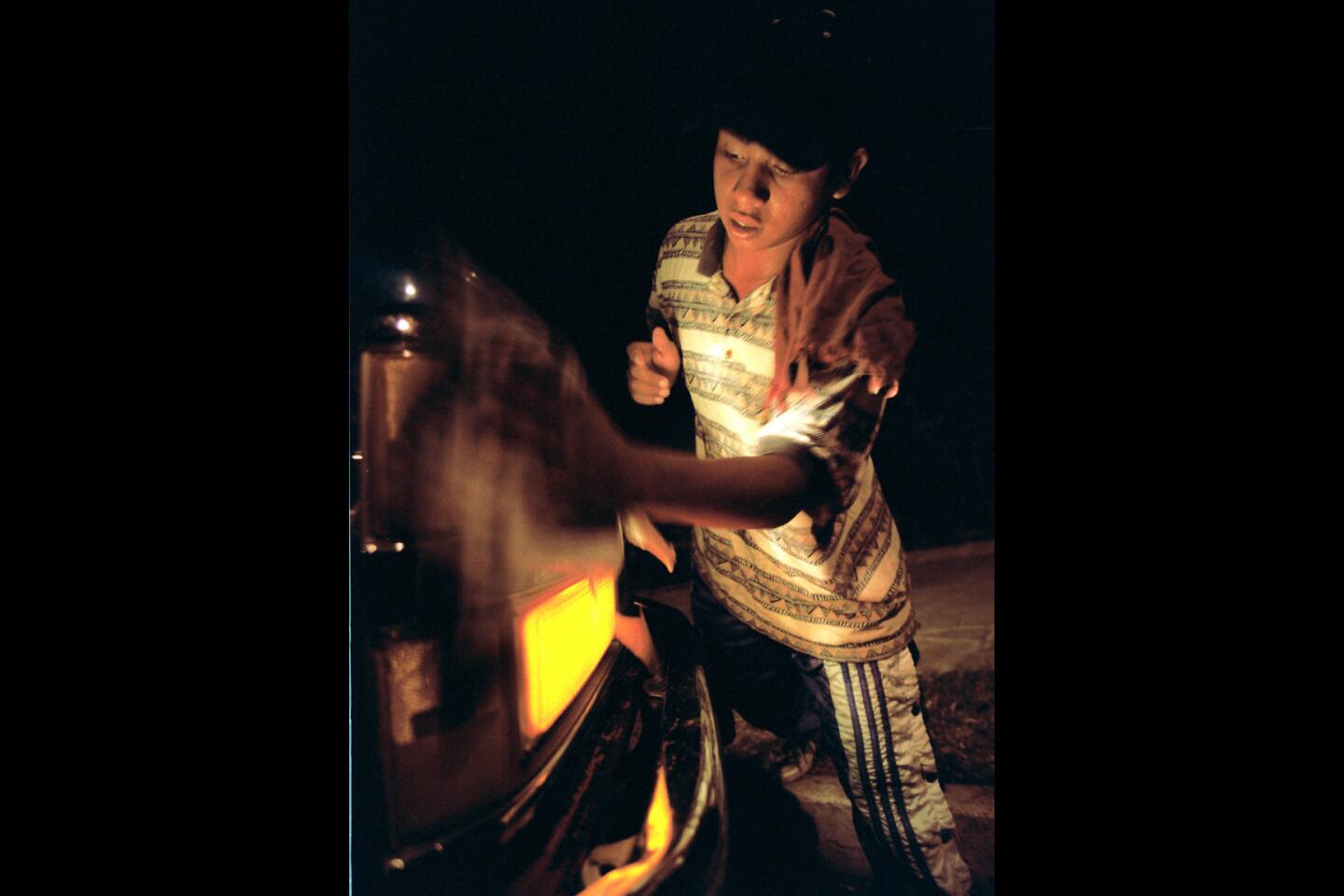

A friend catches six tiny catfish. He builds a fire out of trash. It grows dark. He cuts the fish with a lid from an aluminum can.

Enrique hovers nearby. “You know, Hernan, I haven’t eaten all day.”

Hernan guts the fish.

Enrique stands silently, waiting.

::

A setback

It is May 15. Enrique washes cars. He has a good night and makes 60 pesos. At midnight, he rushes to buy his second phone card. He puts only 30 pesos on it, gambling that his second call will be short. If his old employer finds Aunt Rosa Amalia and Uncle Carlos and gets his mother’s number, then it won’t take many minutes to call his boss a second time and pick it up.

Enrique saves his other 30 pesos for food.

He and his friends celebrate. Enrique drinks and smokes some marijuana. He wants a tattoo. “A memory of my journey,” he says.

El Tirindaro offers to do it free. He shoots up to steady his hand.

Enrique wants black ink.

But all El Tirindaro has is green.

Enrique pushes out his chest and asks for two names, so close together they are almost one. For three hours, El Tirindaro digs into Enrique’s skin. In gothic script, the words emerge:

EnriqueLourdes.

His mom, he thinks happily, will scold him.

The next day just before noon, he stirs from his dirty mattress. He is hungry. Hours pass. His hunger grows. Finally, he cannot stand it. He retrieves the first phone card from the friend who is holding it, and he sells it for food.

Worse, he is so desperate that he sacrifices it at a discount, for 40 pesos. He saves a few pesos for the next day and uses all of his money to buy crackers, the cheapest thing that will fill his stomach.

Now he has gone from two phone cards to one, worth only 30 pesos. He regrets surrendering to his hunger. If only he can earn 20 pesos more. Then he will go ahead and phone his old boss and hope that his aunt or uncle will call back on their own, so he won’t need a second card.

But someone has stolen his bucket. A friend at camp lends him one. He trudges back out to the car wash across from the taco stand. He sits on the bucket. Carefully, he pulls up his T-shirt. There, in an arch just above his belly button, is his tattoo, painfully raw.

EnriqueLourdes. Now the words mock him.

For the first time, he is ready to go back home. But he holds back his tears and lowers his shirt.

He refuses to give up.

::

The moment

He considers crossing the Rio Grande by himself. But his friends at camp warn him against it.

They talk about river bandits who kill, a man sucked under by a whirlpool, dogs at Border Patrol checkpoints that respond to German and can smell sweat, the 120-degree desert, diamondback rattlers, saucer-sized tarantulas and wild hogs with tusks. Some immigrants, dehydrated and delirious, kill themselves. Their leathery corpses sway from belts around their necks on whatever is sturdy and tall. Water jugs lie empty at their feet.

El Hongo listens. Finally, he decides against going alone. “Why should I die doing this?” he asks himself. Somehow, he will call his mother and ask her to hire El Tirindaro.

On May 18, he awakens to find that someone has stolen his right shoe. He spots a sneaker floating near the riverbank. He snags it. It is for a left foot. Now he has two left shoes. Bucket in hand, he hobbles back to the taco stand, begging along the way. People give him a peso or two. He washes a few cars, and it starts to rain. Astonishingly, he has put together 20 pesos in all.

That is enough to trade in his 30-peso phone card for one worth 50 pesos.

He will use the 50 peso card to call his old boss at the tire store. If the boss reaches his aunt and uncle, and if they know his mother’s number, and if his aunt or uncle will call him back ...

It is May 19. Father Leonardo Lopez Guajardo at Parroquia de San Jose is known to let migrants phone from the church if they have cards. Each day, he serves as their telephone assistant. In flip-flops, he pads to the door every 15 minutes or so and summons someone for a return call.

In late afternoon, Enrique reaches his old boss with his request. Two hours later, the padre bellows Enrique’s name. As always, word spreads through the courtyard like wildfire: Someone named Enrique has a phone call.

“Are you all right?” asks Uncle Carlos.

“Yes, I’m OK. I want to call my mom. I’ve lost the phone number.”

Somehow, his boss has neglected to tell them this. Do they have it with them? Aunt Rosa Amalia fumbles in her purse. She finds the number. Uncle Carlos reads it, digit by digit, into the phone.

Ten digits.

Carefully, Enrique writes them down, one after another, on a shred of paper.

Just as Uncle Carlos finishes, the phone dies.

Uncle Carlos calls again.

But Enrique is already gone. He cannot wait.

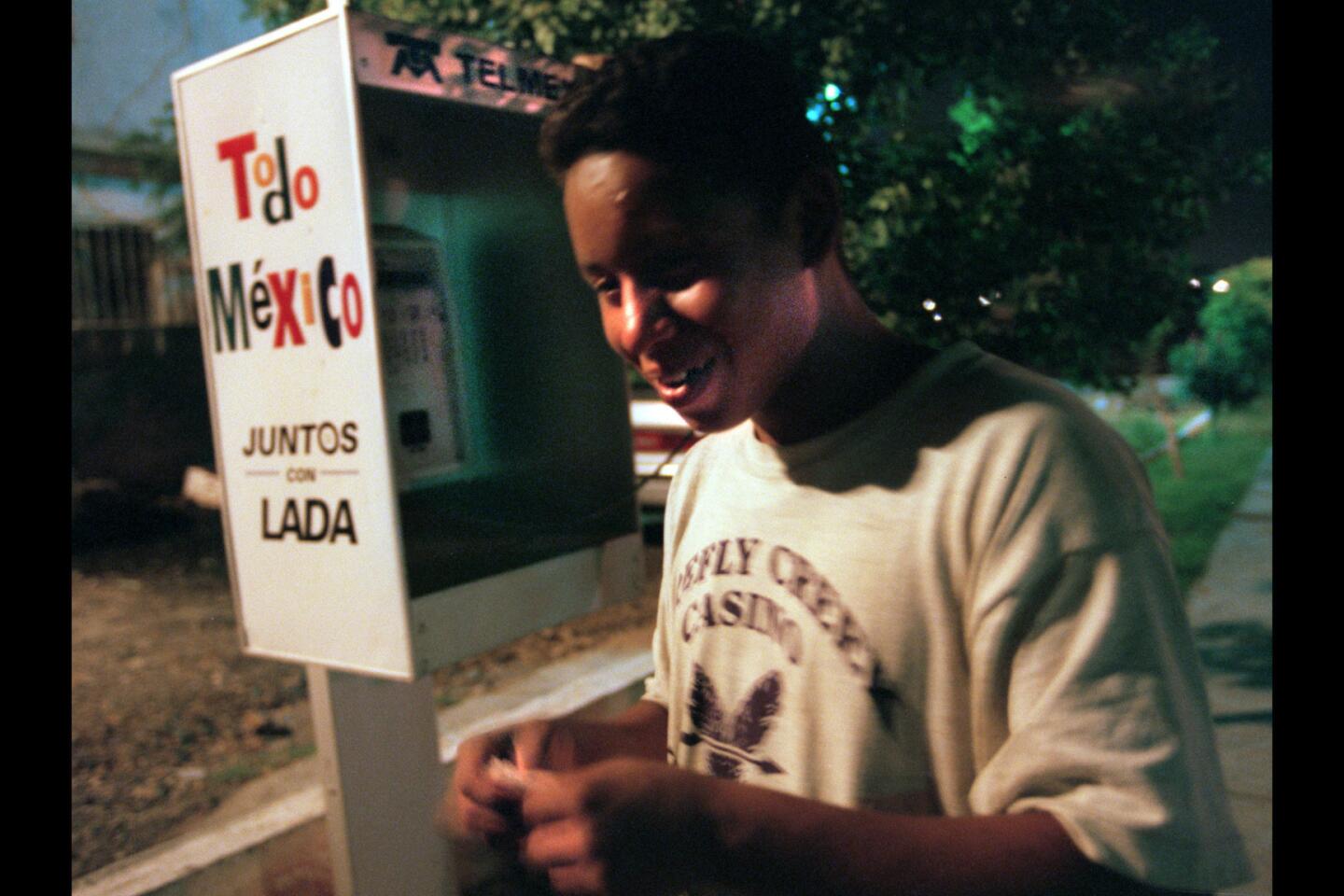

When he talks to his mom, he wants to be alone; he might cry. He runs to an out-of-the-way pay phone to call her. Collect.

He is nervous. Maybe she is sharing a place with unrelated immigrants, and they have blocked the telephone to collect calls. Or she might refuse to pay. It has been 11 years. She does not even know him. She had told him, even harshly, not to come north, but he has disobeyed her. Each of the few times they have talked, she urged him to study. This, after all, was why she left--to send money for school. But he has dropped out of school.

Heart in his throat, he stands on the edge of a small park two blocks from the camp. Next to the grass is a Telmex phone box on a pole.

It is 7 p.m. and dangerous. Police patrol the park.

Enrique, a slight youngster with two left shoes, pulls the shred of paper from his jeans. They are worn and torn; he is too tattered to be in this neighborhood. He reaches for the receiver. His T-shirt is blazing white, sure to attract attention.

Slowly, carefully, he unfolds his prized possession: her phone number.

He listens in wonderment as his mother answers.

She accepts the charges.

“Mami?”

At the other end, Lourdes’ hands begin to tremble. Then her arms and knees. “Hola, mi hijo. Hello, my son. Where are you?”

“I’m in Nuevo Laredo. Adonde estas? Where are you?”

“I was so worried.” Her voice breaks, but she forces herself not to cry, lest she cause him to break down too. “North Carolina.” She explains where that is. Enrique’s foreboding eases. “How are you coming? Get a coyote.” She sounds worried. She knows of a good smuggler in Piedras Negras.

“No, no,” he says. “I have someone here.” Many smugglers deliver their clients to bandits. Enrique trusts El Tirindaro, but he costs $1,200.

She will get the money together. “Be careful,” she says. Go to a hotel. Get the telephone number and the address of Western Union in Nuevo Laredo. She will wire money for a room.

“No,” he says. He is camping by the river. But he will call back with the Western Union information, so she can send a little money anyway.

The conversation is awkward. His mother is a stranger. This is probably expensive; he knows that collect calls to the United States from back home in Honduras cost several dollars a minute.

But he could feel her love. He places the receiver in its cradle and sighs.

At the other end, his mother finally cries.

Next: Chapter Six: At Journey’s End, a Dark River, Perhaps a New Life

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.