Trump left his mark on Atlantic City, for better and for worse

ATLANTIC CITY, N.J. — At Evo Restaurant in the now-closed Trump Plaza casino here, white linen and dusty water glasses are still set on the tables, as if someone expected, any minute, the return of the high rollers who once made this spot the quick-beating heart of Donald Trump’s casino empire.

Jack Przybyski of Brooklyn stands on the famed Boardwalk, peers through the window, shakes his head and calls the demise of this city “a shame.” A frequent visitor, he remembers a glitzier time, when Trump brought some of the biggest boxing matches in the world to the Atlantic City Convention Center next door.

That was before Trump lost control of the casinos after a series of bankruptcies and two decades of battles with banks and bondholders. It was also before the financial crisis and competition from other gambling venues pummeled the casino industry here, throwing thousands out of work and pushing the city to the edge of insolvency.

In his Republican presidential campaign, Trump sells himself as a brilliant businessman and consummate dealmaker. With his showman’s knack for positive spin, he depicts his history in Atlantic City, bankruptcies and all, as more proof of his genius for timing.

“I had the good sense — and I’ve gotten a lot of credit in the financial pages … I left Atlantic City before it totally cratered,” Trump said during the first Republican debate.

The real story of Trump’s rise and fall in Atlantic City is more complicated. His casinos were profitable early. As he expanded, though, Trump’s aggressive borrowing and go-go strategy left them laboring under high-interest debt. When he decided to leave, in 2009, the exit was far from smooth and graceful; he gave up after last-ditch battles with bondholders.

Today, some still love him here, even people who lost money. Others have bitter memories.

“He trampled everyone: the shareholders, the bondholders, the employees, the contractors,” said Sebastian Pignatello, who lives in Flushing, N.Y., near where Trump grew up. An investor who headed a stockholders’ committee that tried to recover losses in one Trump bankruptcy, Pignatello says many small businesses had to settle for “pennies on the dollar.”

Trump did not respond to requests for comment.

Trump had already made a name for himself as a brash, young New York developer when, in his mid-30s, he moved into Atlantic City. His first partnership, in 1982 with the Holiday Inn company to build the Trump Plaza, was sealed after a bit of Trump hokum. In his book “The Art of the Deal,” Trump said he had the site filled with earthmoving equipment to convince executives that construction was moving fast.

When Hilton Corp. failed to win a New Jersey gaming license, Trump snapped up its already-built casino and christened it Trump’s Castle; it opened a year after the Trump Plaza, in 1985.

Then, after a boardroom tussle over control of another firm, Resorts International, Trump ended up with the biggest property of all: the Taj Mahal, then the largest of the city’s casinos.

The Taj was a monument to excess — more than 500 feet high, 17 acres of minarets, mirrors, purple carpets, elephants and giant chandeliers. By the time it opened in 1990, Trump ruled as the undisputed king of Atlantic City, with 25% of the casino market.

At a cost of over $1 billion, financed at interest rates as high as 14%, the Taj Mahal was a huge gamble. It never paid off.

In 1990, when an industry analyst predicted the property would not generate enough money to pay off the bonds, Trump erupted in outrage and wrote a letter to the analyst’s employer, brokerage firm Janney Montgomery Scott, threatening “a major lawsuit.” The analyst, Marvin Roffman, was fired. But in October of that year, with the economy slowing down, Trump missed the first bond payment. The next year, the Taj Mahal was in bankruptcy court.

Roffman eventually won $750,000 from the brokerage firm in arbitration, sued Trump for defamation — reaching a confidential settlement — and started his own successful investment business.

The Taj Mahal’s “debt load was just outrageous,” Roffman said in an interview. “The interest alone was $95 million a year.”

With money running out, Trump’s father, Fred, sent a lawyer to Trump’s Castle to buy $3.5 million worth of casino chips, without playing them, in what amounted to an immediate cash infusion. State regulators later fined the casino $30,000 for the maneuver, but the business was allowed to keep the money.

The crash left Trump’s business hundreds of millions of dollars in the hole, but he avoided a personal bankruptcy, as he stresses in Republican debates. He was put under strict controls by his bankers, including an allowance that a former Trump representative put at $450,000 a month. Trump sold his 281-foot yacht, the Trump Princess, and his Trump Shuttle airline.

Trump and his lawyers convinced the banks that foreclosing on the casinos would be worse than allowing them to stay open in Trump’s hands and persuaded state casino regulators not to yank his licenses, even though operators were supposed to be financially stable.

“It was hard then, and it’s even harder now, to justify” that decision, said Steven P. Perskie, who chaired the state Casino Control Commission at the time. Perskie, a former Democratic state assemblyman who helped write the law that brought casinos to Atlantic City, said he wanted to avoid a fire sale of three casinos at once.

Many people, however, lost money, including contractors and other local businesses that were stuck with unpaid bills when Trump took his properties into bankruptcy court.

Bill Gamble, a carpet installer from Atlantic City, said he had to go to court after one Trump casino shorted him about $22,000.

“He’s a real conniver,” Gamble said. “He’s ruthless.”

“What kind of ethics are we talking about here?” said Pignatello, the head of the stockholders committee, who, along with other investors, ended up recovering some of his money in a bankruptcy settlement.

Trump was not the only Atlantic City operator to get badly overextended in the 1990s. When business picked up again, Trump recovered and went public, raising money in a stock sale.

“I have tremendous confidence in the future of Atlantic City and my hotels in particular,” Trump wrote in a 1997 book, “The Art of the Comeback.”

“Time, I believe, will prove me right.”

But the casinos again were dragged down by debt. By 2004, Trump was back in bankruptcy court; he came out of that one with just a 25% stake in Trump Hotels and Casino Resorts. In 2009, Trump Entertainment Resorts, a successor company, was in bankruptcy again after bondholders rejected Trump’s last-ditch proposal to retake control. That one ended with him controlling just 10%.

“From a financial point of view, he left Atlantic City with his tail between his legs,” said Perskie. Trump’s management of the casinos is “hardly a model of financial probity or business acumen,” he said.

In Perskie’s view, Trump “created an artificial situation in which he had no personal exposure and then ran away from the failure.”

Since then, Trump has continued to prosper as a reality television star and developer, but the fortunes of Atlantic City have continued to sink. Four casinos closed and three others are in trouble. Unemployment is among the worst in the country.

Trump can’t be blamed for the city’s collapse, but he doesn’t deserve credit for his casino management either, said one analyst who has followed the industry since the 1980s.

“You can’t deny the way he ran the properties while he was in charge led to the problems they confronted later on,” said Roger Gros, publisher of Global Gaming Business magazine. “He put his properties in so much debt that subsequent managers couldn’t manage them properly.”

Even so, some people in Atlantic City still love Trump — even those who lost money when his casinos landed in bankruptcy court.

Billy Gabriel Jr. is now the fourth generation involved in his family business, Paris Produce Co., which has been supplying Atlantic City hotels for nearly a century.

“The whole area took a beating” with the Trump bankruptcies, he said, adding that the pain was just as bad when other casinos went under. Gabriel said his company recovered most of what he was owed. And, in a phone interview, he said he still likes Trump — and was even wearing one of Trump’s “Make America great again” hats.

“If a guy used a loophole in the law to benefit himself, more power to him. Wouldn’t you do the same thing?” Gabriel said.

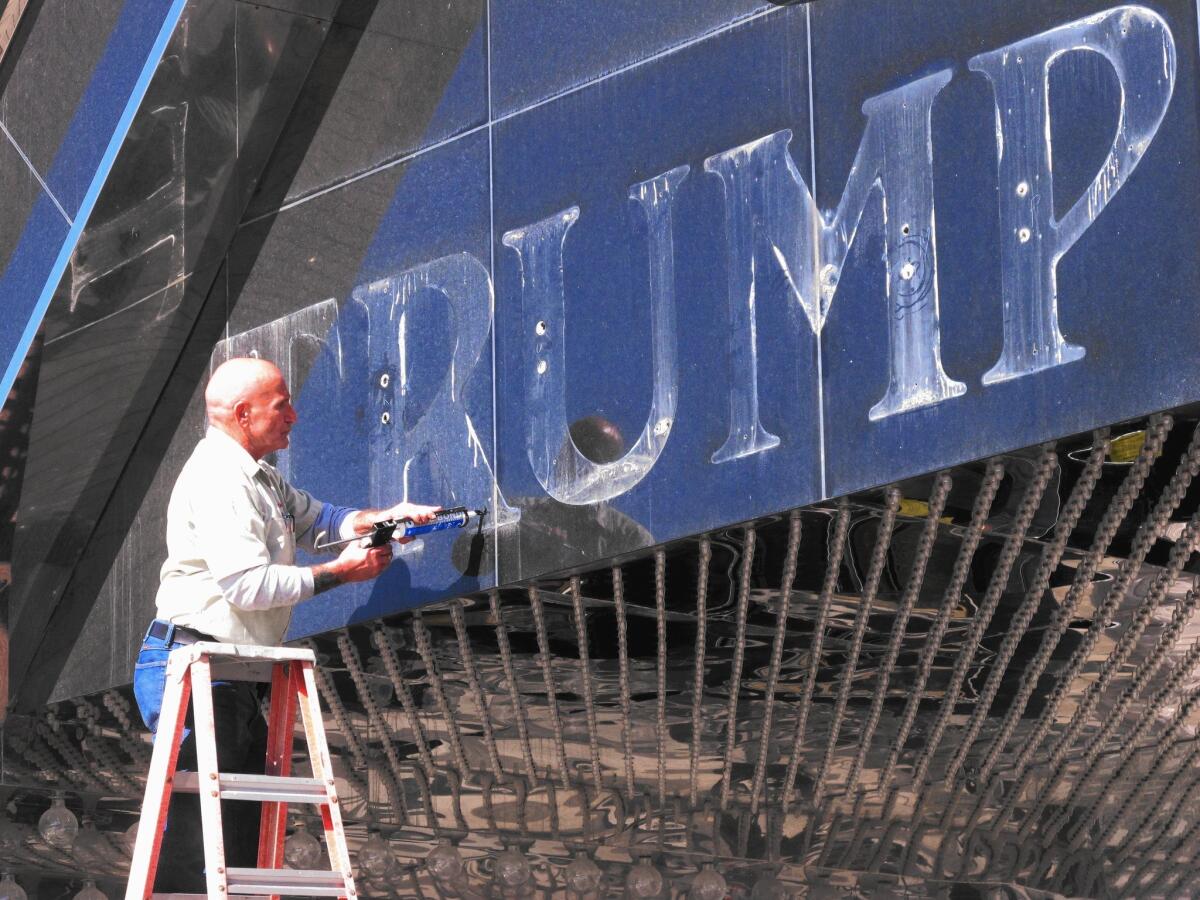

At one point, Trump sued to have his name taken off the casinos. At the end of the Atlantic City Expressway, at the old Trump Plaza, a giant white wall now greets cars entering the city. Trump struck a deal to leave his name on the Taj Mahal, where the massive casino floor is now mostly deserted, and Trump’s portrait still gazes out over a few customers in a gift shop.

“I like thinking big,” a sign quotes him as saying.

During the debate, Trump said his record of company bankruptcies here was nothing to be ashamed of. “I made a lot of money in Atlantic City, and I’m very proud of it. ... Very, very proud.”

Twitter: @jtanfani

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.