Capitol Journal: In the state budget, too many good programs can sometimes be bad

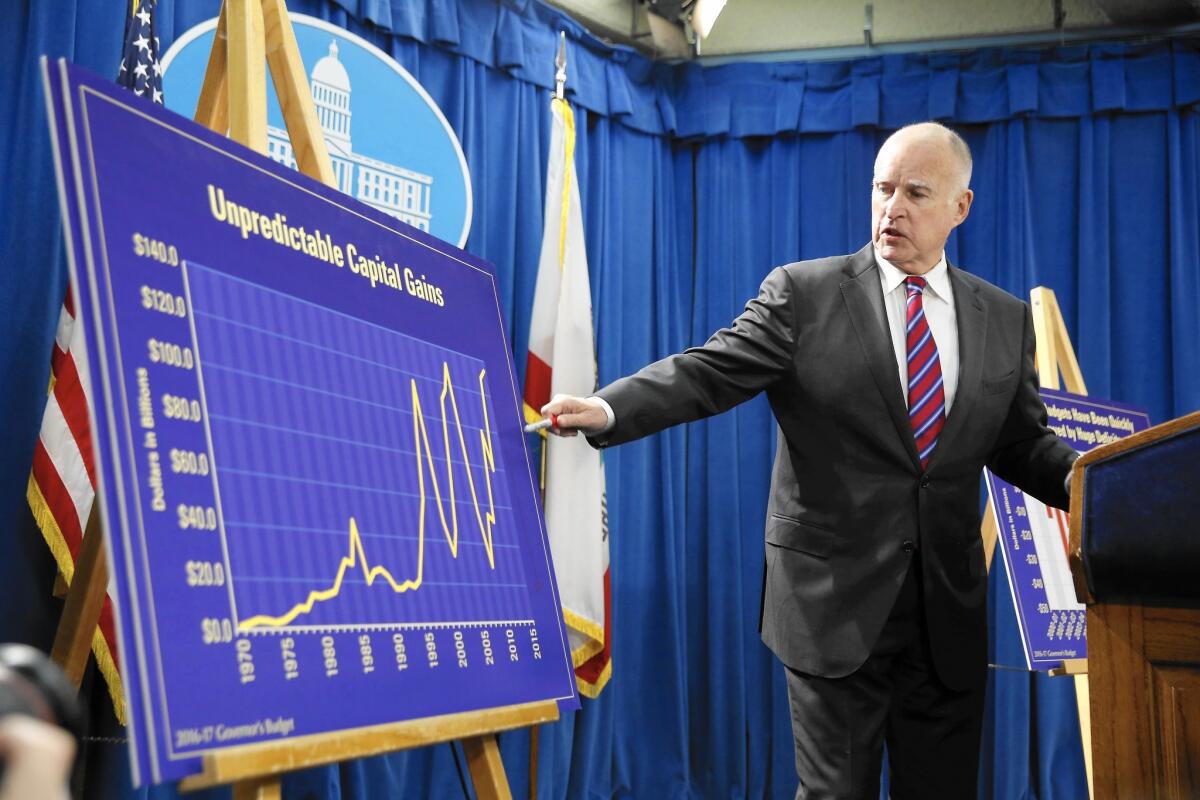

Gov. Jerry Brown discusses his proposed 2016-17 state budget.

SACRAMENTO — Gov. Jerry Brown’s new state spending plan could be called a chicken budget — as in the chickens are coming home to roost.

Not bad chickens, mind you. But expensive.

The birds I’m talking about are programs, mostly worthwhile, that Sacramento previously enacted. Now they have to be paid for.

Dig deep into Brown’s $171-billion budget proposal for the next fiscal year and you’ll find a flock.

California’s generous treatment of Obamacare, for example.

This state was the first to embrace the federal Affordable Care Act. We even bought into an option that expanded Obamacare’s usage through Medi-Cal, our healthcare program for the poor.

The feds gave us a free trial period for the optional expansion. But starting next year, we’ll have to share the cost. Brown budgeted $740 million for that. And he pointed out that by 2020, the state’s annual tab will approach $2 billion.

Medi-Cal also has been extended to immigrant children in the country illegally. Last week, the governor set aside $182 million for that.

In all, rapidly growing Medi-Cal covers more than a third of the state’s population. Obamacare has added 5 million people alone. Brown pegged the annual general fund cost for Medi-Cal at $19 billion.

“Compared to other states,” the budget document says, “California is providing higher levels of [Medi-Cal] services while receiving lower federal reimbursements and maintaining lower-than-average costs per case.”

That cost per case is because California offers about the lowest Medi-Cal doctor fees in the country. It angers physicians, and many refuse to treat Medi-Cal patients. So at some point, this also will need to be fixed with tax dollars.

All that is part of the reason Brown is trying to enact a new tax on managed care plans.

The Obama administration has ordered California to stop taxing only Medi-Cal plans, leaving a $1.1-billion budget hole. The governor last year proposed taxing all managed care plans — Medi-Cal or not — but Republicans objected. The governor now is suggesting a compromise.

Asked by reporters for details, Brown begged off. “It’s extremely complex,” he said. “Very few people understand it, so I’m not going to try to explain it to you because I couldn’t explain it to you if I wanted to.”

Basically it involves taxing Medi-Cal plans at a higher rate than the others. Also, there would be separate tax breaks for the non-Medi-Cal plans, so they’d actually come out ahead. The state would still qualify for a load of federal matching dollars.

Republicans shouldn’t oppose that. But who knows!

Another chicken: California last year began providing driver’s licenses to immigrants who are here illegally. That was long overdue because it assured that these motorists know the rules of the road.

But to handle the driver applications, four new processing centers were opened, office hours were extended at other DMV offices and 1,000 new employees were hired. More than 600,000 licenses were issued.

It’s one reason Brown proposed increasing the annual vehicle registration fee by $10. Without it, the budget document warned, some DMV offices might have to be shuttered.

Another example: On Jan. 1, the state minimum wage rose to $10 an hour, benefiting 2.2 million California workers. That doesn’t just hit businesses, it also affects state services, especially home care. Brown signed that minimum wage bill. And last week, he budgeted $250 million to pay for it.

But he cautioned against voting for a potential November ballot measure that would jack up the minimum to $15. That could cost the state $4 billion annually by 2021, he said.

“Raising the minimum wage can be good, but it has to be done very carefully,” Brown said. “It has to take into account what other programs can be cut to finance it. Or what taxes are going to be generated to pay for it.”

What a novel concept in Sacramento.

“These are all good things,” Brown continued, “but too many goods too quickly become bad.”

At another point, in commenting on a Democratic legislative proposal to spend $2 billion on housing for mentally ill homeless, the governor said: “That’s another good. We’ve got to weigh it, [but] this is not a candy store where you can pick out whatever you want. You’ve got to choose.”

Fortunately for the most financially vulnerable and politically weakest among us, Brown chose to provide the first benefit increase in a decade for the 1.3 million impoverished aged, blind and disabled.

But mostly he seemed like a doomsday preacher wearing a sandwich board proclaiming: “The End Is Near.”

“If you don’t remember anything else, just remember: Everything that goes up comes down,” he said, referring to the economy. We’re overdue for another recession, he warned. Although the treasury is overflowing now, if the state follows liberal Democrats on a spending spree “and we get a recession, you get a $43-billion deficit within three years.”

I didn’t hear anything about the $68-billion bullet train, however.

Brown proposed stashing more money in California’s new rainy-day fund that’s supposed to protect state services against the next downturn. But that fund would be a piddling in a deep recession.

What’s really needed is major tax reform that doesn’t rely so heavily on rich people’s roller-coaster capital gains. But there’s no stomach for that in the Capitol.

Meanwhile, Brown — as all governors — holds the best budget cards because he can sign or veto legislators’ bills. He rules the roost.

Twitter: @LATimesSkelton

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.