Critics accuse Gov. Jerry Brown of neglecting California’s poor

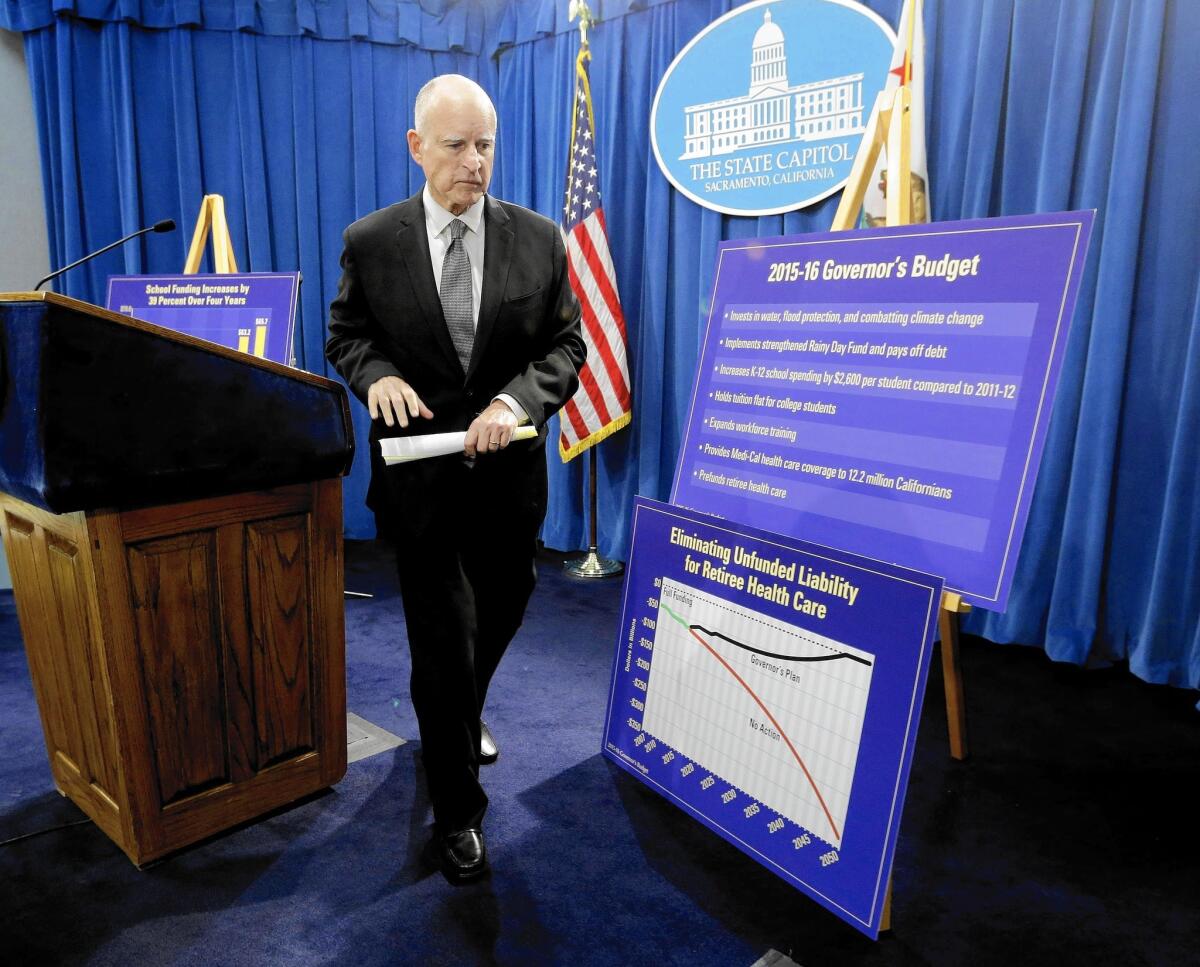

SACRAMENTO — When Gov. Jerry Brown unveiled his latest budget proposal last week and the topic turned to Californians’ financial struggles, he became uncharacteristically personal.

He described getting behind the wheel to drive mothers to shelters in Oakland, where he spent eight years as mayor. And he talked about a young relative who attended a $40,000-a-year university but lives at home because her salary is only $30,000 at a “so-called high-tech business in San Francisco.”

“These are challenges. They are challenges within my own family,” Brown said. “I don’t have all the answers.... I don’t know if anybody does.”

His sympathetic words, though, didn’t convince many of his critics, including some Democrats, who accused him of not doing enough for those mired in poverty or struggling to make a living.

They noted that welfare grants remain lower than before the recession, doctors willing to work for the state’s low payments can be hard to find, and a quarter of Californians still live in poverty.

Brown defended his record, saying that he’s raised the minimum wage, made more people eligible for public healthcare and directed more money to poor school districts — and that a third of his proposed general fund would help the needy.

The debate, which has simmered for years as Brown worked to stamp out deficits by keeping a lid on spending, threatens to boil over as liberal lawmakers make clear their desire to use the state’s rebound to increase aid to people passed over by the economic turnaround.

“We do have people that are suffering,” said Assembly Budget Committee Chairwoman Shirley Weber (D-San Diego). “We need to look at ways in which we look at not only the big picture and the long term, but also the immediate.”

The California Budget Project, a think tank that advocates for low-income families, issued a report Monday saying the governor’s budget failed to “lay out a plan to tackle California’s biggest challenges: high levels of unemployment and poverty, widening income inequality and a safety net severely weakened by years of funding cuts.”

Brown says there’s only so much the state can do with the money it has.

“There’s always someone in need. In fact, there’s millions of someones in need,” he said last week. “And we’re doing quite a lot. More than most states.”

Brown’s budget blueprint includes $17.7 billion from the general fund for healthcare for poor Californians and $1.7 billion in financial aid for university students. Home care for low-income elderly and disabled residents would get $3.4 billion, which includes $483 million to restore a recession-era cut in home care for the group.

But advocates say not enough money has been returned to government programs such as CalWORKs, California’s main welfare program, which provides cash assistance to 1.3 million Californians, of whom 1 million are children.

The governor previously agreed to increase welfare grants to a maximum of $704, starting in April. That’s equivalent to 2003 levels, but worth $200 less in today’s dollars because of inflation.

“They’re still a fraction of what they should be if we wanted to ensure that the poorest children in this state have a minimally decent standard of living,” said Frank Mecca, executive director of the County Welfare Directors Assn. of California.

A final budget is due at the end of June, and Brown will be negotiating the spending plan with two top lawmakers who have deep personal experiences with poverty.

Assembly Speaker Toni Atkins (D-San Diego) grew up without indoor plumbing in Virginia, where her father was a miner and her mother was a seamstress. Senate leader Kevin de León (D-Los Angeles) would tag along with his mother for two-hour bus rides to rich neighborhoods where she would clean houses. Both of them went to free clinics for healthcare.

Brown’s father, Pat, was governor of California, and the younger man attended UC Berkeley and Yale Law School.

One of Brown’s most dramatic encounters with poverty came in the 1980s, after he served his first two terms as governor, when he volunteered with Mother Teresa in India, and tended to impoverished, dying patients. He told a Times reporter that he wanted to break from “the sheltered perspective of California affluence.”

Years later, as mayor of Oakland, Brown lived in a gritty downtown neighborhood. He cited that experience last week.

“I came in contact with low-income people of many persuasions,” he said. “I think I do have a sensitivity to people’s difficulties in life.”

Assemblyman Mark Stone (D-Scotts Valley) wants California to join 25 other states in creating a tax break for the working poor.

Legislative analysts estimated that such a policy would cost the state $400 million to $1 billion a year, depending on how the tax credit was crafted, plus millions more in administrative costs.

Stone is confident there’s room in the budget for his proposal. He noted, for example, a cluster of corporate tax breaks that cropped up at the end of last year’s legislative session, despite Brown’s insistence on a tight-fisted spending plan months earlier.

“An earned income tax credit is the same kind of investment in our economy, it’s just getting the money in the pockets much further down the economic strata who need it the most,” Stone said.

The U.S. Census Bureau says California’s poverty rate is 23.4%, the highest in the country, when factors such as the cost of living are taken into account.

Sarah Bohn, a researcher at the Public Policy Institute of California, said part of the problem is a decades-long shift in the state’s labor market from skilled jobs in, say, manufacturing to a service economy with lower wages for jobs in restaurants or childcare, for example.

Low-paying work is a problem faced by Brown’s grandniece, the young relative who makes $30,000 a year and lives at home. Asked last week what he would tell her about her predicament, he responded:

“I’d say, we’re not going to adopt the socialist system with Leninism and all the rest of it.... The modern economy is based on individual reward, with most of the money moving toward the top. That’s the system.”

He added, “We try to mitigate that.”

Twitter: @chrismegerian

Twitter: @melmason

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.