Pop legend Whitney Houston dies at 48

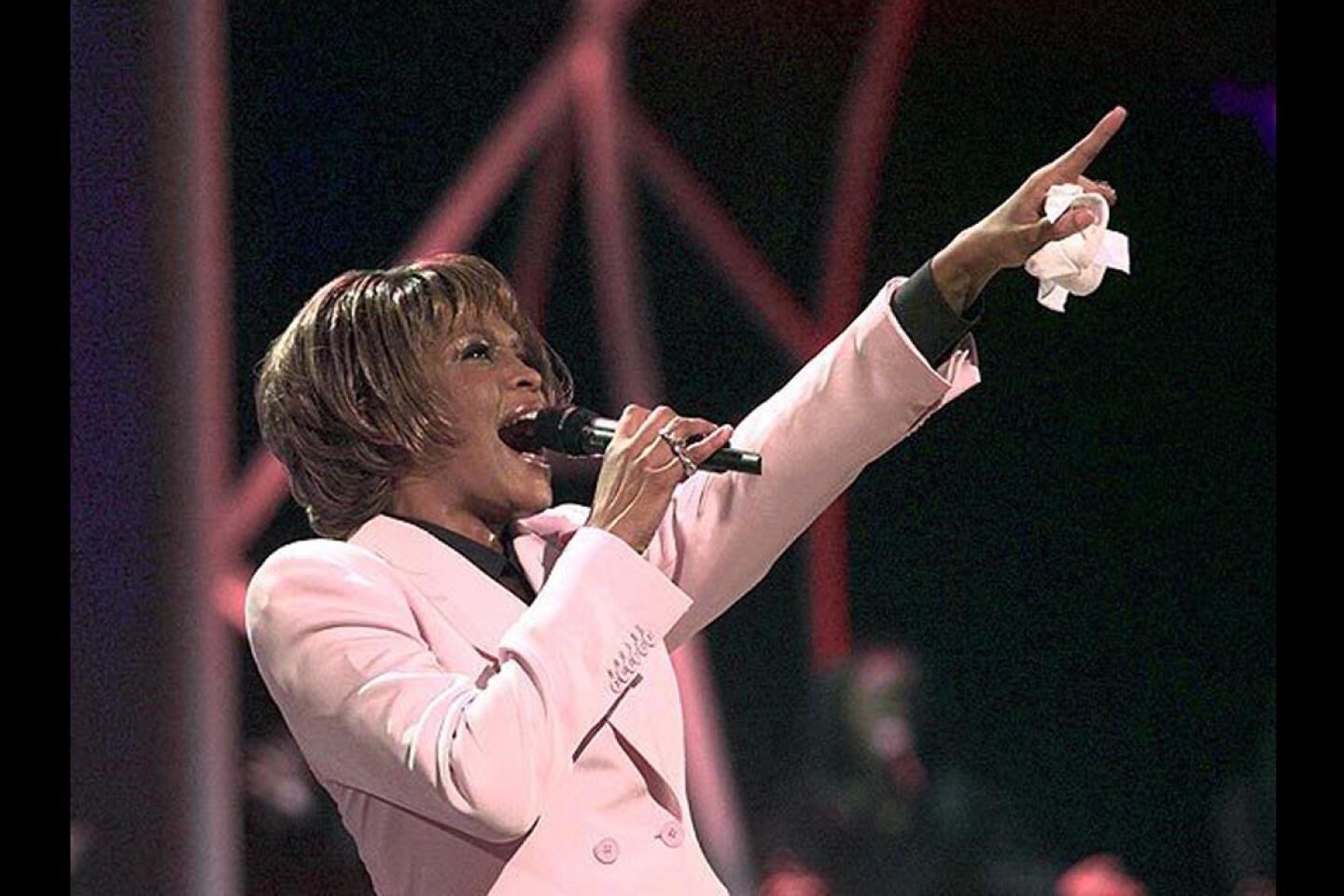

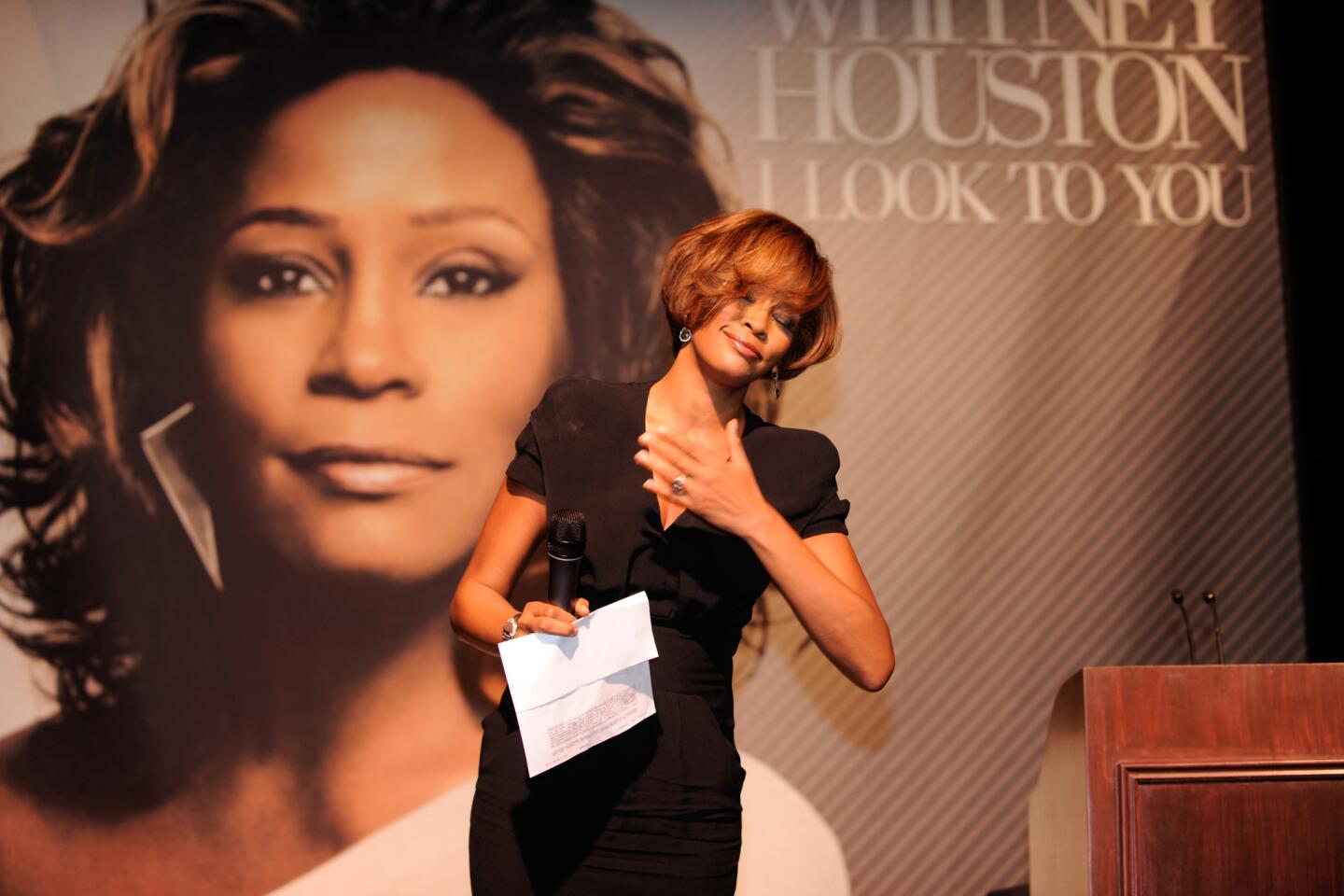

Whitney Houston, a willowy church singer with a towering voice who became a titan of the pop charts in the 1980s and 1990s but then saw much of her success crumble away amid the fumes of addiction and reckless ego, has died. She was 48.

Kristen Foster, a publicist, announced Saturday that the singer had died, and police sources later confirmed that she was found unresponsive in her room at the Beverly Hilton Hotel about 3:30 p.m. Paramedics performed CPR on her, but she was pronounced dead about 4 p.m., Beverly Hills Police Lt. Mark Rosen told KTLA News. An investigation into the cause of death is pending.

On Thursday afternoon at the hotel, Houston drew the attention of reporters and security staff with her erratic behavior, dripping sweat and disheveled clothes. The singer was disruptive at that day’s rehearsals for music mogul Clive Davis’ annual Grammy industry party and showcase; that party at the Hilton on Saturday night was supposed to include a performance by Houston.

PHOTOS: Whitney Houston | 1963-2012

Late Saturday, Davis told those assembled at the party that he had a “heavy heart” and was “personally devastated” by Houston’s death, but “simply put, Whitney would have wanted the music to go on, and her family has asked for us to carry on.”

The star’s professional decline had become a familiar part of her public saga. Her haggard appearance at times shocked fans who had once been drawn to the singer’s world-class smile and approachable glamour in music videos, album covers, concerts and, later, hit films. Songs like “I Will Always Love You” and “Saving All My Love for You” had women around the world singing along with the star, but by the end of the 1990s they barely recognized her.

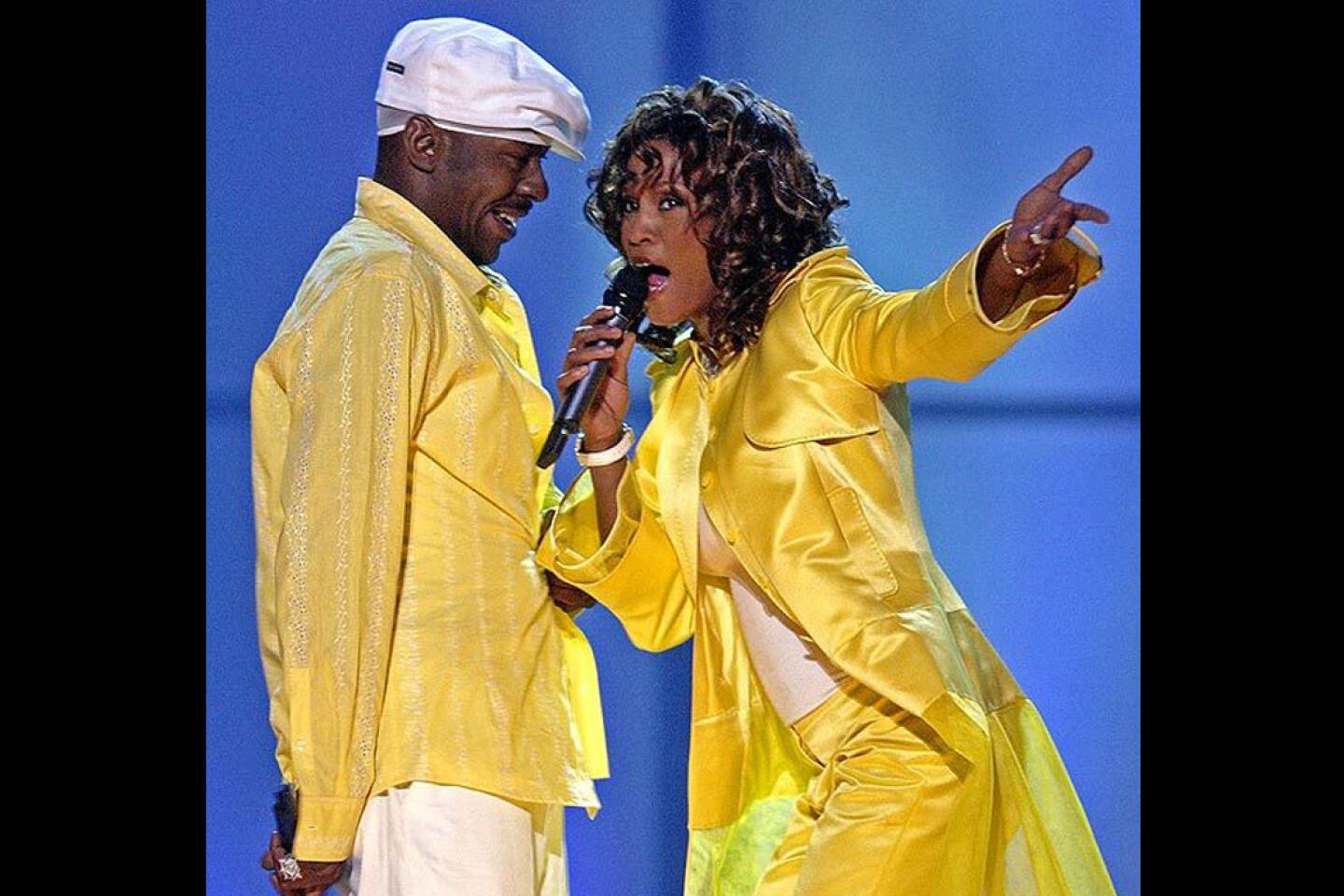

As Houston’s public persona veered into something darker and more volatile, many fans pointed to her relationship with Bobby Brown as the axis on which her life seemed to be spinning so madly. She acknowledged that she was immersed in drugs, and the toll on her voice and her appearance was difficult to watch.

“The biggest devil is me,” the singer told ABC’s Diane Sawyer in a notorious 2002 interview. “I’m either my best friend or my worst enemy.”

Brown was at Houston’s side as she said that. Their 14-year marriage, invariably described as tumultuous, was tarnished by drug abuse, Brown’s run-ins with the law and allegations of domestic abuse. It became fodder for the tabloids and entertainment shows and for a year was on display in the reality show “Being Bobby Brown.”

The two superstar singers met at the 1989 Soul Train Music Awards and married three years later. To some, it seemed an odd match, the glamorous pop star and the onetime New Edition bad boy. “When you love, you love. I mean, do you stop loving somebody because you have different images? You know, Bobby and I basically come from the same place,” she explained to Rolling Stone. “I am not always in a sequined gown. I am nobody’s angel. I can get down and dirty. I can get raunchy.”

Houston divorced Brown in 2007, winning custody of their daughter, Bobbi Kristina Brown. At the court session in Orange County, Houston testified that her daughter could not depend on her father. “He’s unreliable,” Houston said, according to the Associated Press. “If he says he’s going to come, sometimes he does. Usually he doesn’t.”

In his autobiography, Brown wrote that their marriage “was doomed from the very beginning,” saying that they separated in the first year and several times in the years after. He said he believed she had married him “to clean up her image.” Brown also admitted he was not faithful to Houston.

Whitney Elizabeth Houston was born Aug. 9, 1963, in Newark, N.J., and powerful female voices and the sound of choirs were in her ears before she could walk or talk. Cissy Houston, her mother, was a gospel singer and back-up singer who worked with the likes of Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett and Dusty Springfield. Aretha Franklin was the youngster’s godmother, and Dionne Warwick and Dee Dee Warwick were her cousins. There was little doubt that young Whitney would follow their career paths.

In her family’s basement — which was Madison Square Garden in her imagination — she would belt out “Respect” and bask in the applause that she might have considered her birthright. By high school she was singing back-up for Chaka Khan and Lou Rawls and had also embarked on a modeling career that put her in the glossy spreads of Seventeen and Glamour magazines.

At a showcase in Sweetwaters supper club in Manhattan — she could sing at 19 but wasn’t old enough to buy a drink — she was spotted by Davis, the music mogul who has become legendary for his ear and his success in guiding the early careers of Rod Stewart, Carlos Santana, Barry Manilow, Alicia Keys and Kelly Clarkson. Davis saw in Houston a rare bundle of raw talent, beauty and pedigree. He spent two years and $250,000 to prepare and package her before releasing her 1985 debut album, “Whitney Houston,” which would became a mega-seller.

“Whitney Houston” became the first album by a new female artist to yield three No. 1 singles: “Saving All My Love for You,” “How Will I Know” and “The Greatest Love of All.” Critics moaned that the material was too flimsy for such a prodigious instrument, but Houston reveled in the success. She became a major crossover star and, with her church background and relatively wholesome aura, she was the rare female recording star who was young and attractive but not overtly sexualized on stage and on screen.

Houston’s follow-up album, “Whitney,” in the summer of 1987, delivered hit after hit with “I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me),” “Didn’t We Almost Have It All,” “So Emotional,” and “Where Do Broken Hearts Go.” For her career, her sales totals would become dizzying: By some accounting, she sold more than 170 million albums, singles and videos in the pre-digital marketplace.

Houston’s stirring rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” at the 1991 Super Bowl became a signature as well and a massive fundraiser for the American Red Cross. More than sales units, Houston had stepped to the center of pop culture in a way that would make her a powerful influence on several generations of singers, especially Mariah Carey, Christina Aguilera, Alicia Keys, Queen Latifah and Jennifer Hudson.

Carey, one of the few female stars of Houston’s era who was on a competitive commercial footing, said Saturday she was reeling from the news.

“Heartbroken and in tears over the shocking death of my friend, the incomparable Ms. Whitney Houston,” Carey said. “My heartfelt condolences to Whitney’s family and to all her millions of fans throughout the world. She will never be forgotten as one of the greatest voices to ever grace the earth.”

From topping the pop charts, the next frontier was film, and in 1992 Houston starred with Kevin Costner in “The Bodyguard.” The soundtrack won the 1994 Grammy for Album of the Year and also yielded the hit “I Will Always Love You,” which became the best-selling single by a female artist in music history.

In 1995’s “Waiting to Exhale,” Houston showed that, like Diana Ross, she aspired to a more complex acting persona. And she had recently finished shooting “Sparkle,” a remake of a 1976 Irene Cara film that focuses on the backbeat of addiction in the music industry.

The Hollywood career was made wobbly by the personal issues and the bad press. In 1996, to promote the wholesome film “The Preacher’s Wife,” Houston spoke to the Washington Post about the struggles of separating her Sunday morning reputation from her Saturday night misadventures.

“I’ve just kind of prepared myself for what’s to be expected” from the media, she says. “It still bothers me to hear rumors, but now I’m taking it in stride. It angers me at times, but I’ve decided to have a Christian-like attitude. Being angry destroys the soul. ... It still [hurts]. Everybody wants good press. No one wants lies. Fame is a very curious game. Perfect strangers call you by name. I don’t know what transpires from making a record to ‘I know you.’ ”

Houston amassed rooms full of trophies through the years, including 22 American Music Awards — more than any other woman — and six Grammys. Any awards show she was on was must-see television, although the reasons for that changed through the years.

On Saturday, at Staples Center, rehearsals were underway for the 54th Annual Grammy Awards, which air Sunday on CBS, and news of Houston’s death arrived as a whispered bombshell while Rihanna was on stage singing “We Found Love.” Producers swapped stunned looks and immediately reached for the phones, scrambling to find the right tone and content for a memorial segment on the show. They decided on a short, austere performance by Jennifer Hudson, one of Houston’s clear contemporary disciples.

“It’s too fresh in everyone’s memory to do more at this time, but we would be remiss if we didn’t recognize Whitney’s remarkable contribution to music fans in general, and in particular her close ties with the Grammy telecast and her Grammy wins and nominations over the years,” said Grammy executive producer Ken Ehrlich, a key figure in the Grammys since the early 1980s.

Ehrlich said it was difficult for him to watch Houston’s decline through the years as addiction and chaos took away too much of her golden success story and her singular voice.

“It’s hard to think of an artist who had such an incredible instrument, not to mention beauty, which made her difficulties in recent years even harder to accept,” Ehrlich said.

Ehrlich recalled one shaky night in New York when word of Houston’s behavior leading up to the awards show spurred him to visit her dressing room at Madison Square Garden to gauge her ability to perform — and he marveled to find that she had already pulled herself together.

A fonder memory was, in the 1980s, watching Grammy director Walter Miller show the young singer how to walk down a set of “TV stairs” — the first ones she had ever navigated.

“She was like a young filly about to head out on the track for her first race, a race you knew she was not only going to win, but would set any number of records,” Ehrlich said.

FULL COVERAGE: Whitney Houston | 1963-2012

Los Angeles Times staff writers John Hoeffel, Randy Lewis, Gerrick Kennedy and Andrew Blankstein contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.