Thomas S. Monson, president of Mormon Church who oversaw an era of change, dies at 90

Reporting from SALT LAKE CITY — For more than 50 years, Thomas S. Monson served in top leadership councils for the Mormon Church — making him a well-known face and personality to multiple generations of Mormons.

A church bishop at the age of 22, the Salt Lake City native became the youngest church apostle ever in 1963 at the age of 36. He served as a counselor for three church presidents before assuming the role of the top leader of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in February 2008.

After a life of church service, Monson died Tuesday at his home in Salt Lake City, according to church spokesman Eric Hawkins. He was 90.

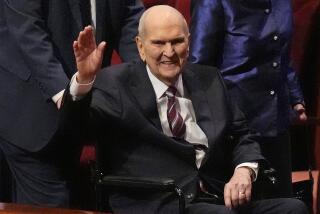

The next president was not immediately named, but the job is expected to go to the next longest-tenured member of the church’s governing Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, Russell M. Nelson, per church protocol.

Monson’s presidency was marked by his noticeably low profile during a time of intense publicity for the church, including the 2008 and 2012 campaigns of Mormon Mitt Romney for president. Monson’s most public acts were appearances at church conferences and devotionals as well as dedications of church temples.

Monson will also be remembered for his emphasis on humanitarian work; leading the faith’s involvement in the passage of the gay marriage ban in California in 2008; continuing the religion’s push to be more transparent about its past; and lowering the minimum age for missionaries.

Mormons considered Monson a warm, caring, endearing and approachable leader, said Patrick Mason, associate professor of religion at Claremont Graduate University. He was known for dropping everything to make hospital visits to people in need. His speeches at the church’s twice-yearly conferences often focused on parables of human struggles resolved through faith.

He put an emphasis on the humanitarian ethic of Mormons, evidenced by his expansion of the church’s disaster relief programs around the world, said Armand Mauss, a retired professor of sociology and religious studies at Washington State University.

Monson often credited his mother, Gladys Condie Monson, for fostering his compassion. He said that during his childhood in the Depression of the 1930s, their house in Salt Lake City was known to hobos riding the railroads as a place to get a meal and a kind word.

“President Monson always seemed more interested in what we do with our religion rather than in what we believe,” Mauss said.

A World War II veteran, Monson served in the Navy and spent a year overseas before returning to get a business degree at the University of Utah and a master’s degree in business administration from the church-owned Brigham Young University.

Before being tabbed to join the church’s governing Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, Monson worked for its secular businesses, primarily in advertising, printing and publishing, including the Deseret Morning News.

Monson married Frances Beverly Johnson in 1948. The couple had three children, eight grandchildren and 11 great-grandchildren. His wife died in 2013.

Monson’s legacy will be tied to the religion’s efforts to hold tight to its opposition of same-sex marriage while encouraging members to be more open and compassionate toward gay and lesbian people as acceptance of the LGBTQ community increased across the county.

At Monson’s urging, Mormons were vigorous campaign donors and volunteers in support of a measure to ban gay marriage in California in 2008. That prompted a backlash against the church that included vandalism of church buildings, protest marches and demonstrations outside church temples nationwide.

In subsequent years, the church began utilizing a softer tone on the issue. In 2015, the church backed an anti-discrimination law in Utah that gave unprecedented protections for gay and transgender people while also protecting religious freedoms.

But the religion came under fire again in the fall of 2015 when it banned baptisms for children living with gay parents and instituted a requirement that those children disavow homosexual relationships before being allowed to serve a mission. The changes were designed to avoid putting children in a tug-of-war between their parents and church teachings, leaders said.

The revisions triggered anger, confusion and sadness for a growing faction of LGBTQ-supportive Mormons who were buoyed in recent years by church leaders’ calls for more love and understanding for LGBTQ members.

One of the most memorable moments of Monson’s tenure came in October 2012, when he announced at a church conference that the minimum age to depart on missions was being lowered to 19 from 21 for women, and to 18 from 19 for men. The change triggered a historic influx of missionaries and proved a milestone for women by allowing many more to serve.

Monson also continued the church’s push toward being more open about some of the most sensitive aspects of the faith’s history and doctrine. A renovated church history museum reopened in 2015 with an exhibit acknowledging the religion’s early polygamous practices, a year after the church published an essay that for the first time chronicled founder Joseph Smith’s plural wives.

Other church essays issued during Monson’s tenure addressed other sensitive topics: sacred undergarments worn by devout members; a past ban on black men in the lay clergy; and the misconception that Mormons are taught they will get their own planet in the afterlife.

The growth and globalization of the religion continued under Monson, with membership swelling to nearly 15.9 million, with more than half outside the United States.

Like his predecessors, Monson traveled the world, visiting countless countries to give speeches, dedicate temples and preach to Latter-day Saints. Under his watch, 27 new temples were planned or built.

The man expected to take Monson’s seat, the 93-year-old Nelson, has been a church apostle since April 1970. Out of respect, his appointment will not be officially named until after Monson’s funeral services.

UPDATES:

9:36 a.m.: This article was updated with reaction and additional details.

This article was originally published at 12:25 a.m.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.