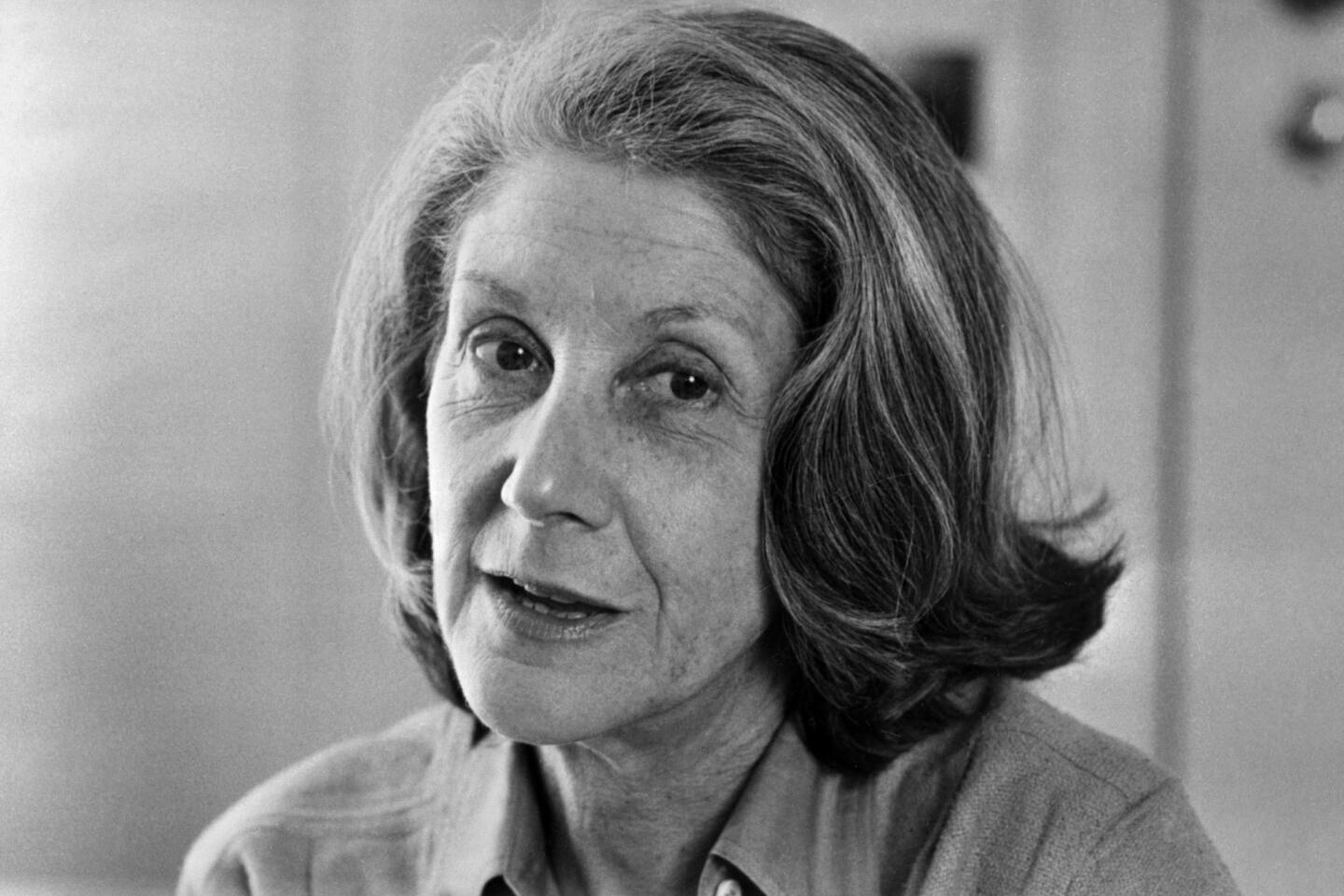

Nadine Gordimer dies at 90; Nobel laureate chronicled apartheid

Reporting from JOHANNESBURG, South Africa — From childhood, Nadine Gordimer understood the cruelties of apartheid.

“I went to the Convent of Our Lady of Mercy,” the daughter of poor South African whites recalled years ago, “but there was no mercy for blacks. I went to dancing classes, blacks were not allowed. The library, which was so precious to me, again, blacks were not allowed. It impinged on my consciousness. I began to ask why.”

By 15, Gordimer was doing more than asking — she began writing stories and then novels, building over the next eight decades a body of work that would earn her fame as one of the finest chroniclers of apartheid in South Africa.

Her characters were a panorama of South African society — blacks and whites, neo-colonials and revolutionaries and others in between — whose lives reflected the strains in a system that caused conflict and confusion for half a century.

Gordimer was a crusading Nobel laureate in literature whose work, including the novels “Burger’s Daughter,” “The Conservationist” and “July’s People,” probed the lives of ordinary South Africans to convey the visible and hidden wounds of racial injustice, corruption and abuses of freedom. She died Sunday in Johannesburg after an illness, her family said. She was 90.

A prickly, astute writer who quoted Franz Kafka to explain her view of literature as “an ax to break up the frozen sea within us,” Gordimer condemned the racist system that for decades was imposed by a white minority on a black majority, saying it cauterized the human heart.

She supported the African National Congress’ liberation struggle, and when Nelson Mandela was released from prison in 1990, Gordimer was among the first people he met. She later turned against the party, accusing it of corruption.

The author of 16 novels and more than two dozen collections of short stories and essays, including three books that were banned under apartheid, she won the Nobel Prize in 1991, the same year that apartheid was lifted.

That year, Times correspondent Scott Kraft wrote of how “this unassuming, strong-willed white woman has used her manual Hermes typewriter to give the world some of the most perceptive and uncompromising works of fiction ever written about her homeland, South Africa.”

But after apartheid, some black critics derided her as a white liberal, belittling her role in helping the world understand the barbarity of the apartheid system. In 1998, four years after the first free elections, “July’s People” was banned from study at schools by the ANC government of the country’s most populous state, Gauteng, which deemed the book “deeply racist, superior and patronizing.”

In her later years, she bitterly castigated the ANC government over a controversial secrecy bill, and wrote about its corruption and betrayal of its people.

Born Nov. 20, 1923, Gordimer was the child of Jewish immigrants. Her father had arrived as a threadbare teenager from Lithuania; he was relieved, Gordimer once said, that as a white in South Africa at least some people were lower than him on the social order. Her mother was a middle-class woman from Britain who felt charitable concern for the plight of blacks “all in a Lady Bountiful context,” Gordimer later said.

Gordimer was raised in a mining town, Springs, and educated at a Catholic convent school and at the University of Witwatersrand. She began writing as a child and, without revealing her age, sent her first short story to a magazine at 15. To her amazement, the magazine published it.

“Now that was an immense thrill, never mind the Nobel Prize,” she later said. “That was when I knew I would be a writer.”

But it was not until apartheid became law in 1948 that her writings achieved their full force. Her first novel, “The Lying Days,” was published in 1953. About 20 years later, in 1974, she won the Booker Prize for “The Conservationist,” considered by some to be her finest work.

When she won the Nobel Prize in 1991, the battle against apartheid was almost won. Mandela had been released from prison, and negotiations on the deal that would secure democratic elections and majority rule were underway.

“Gordimer writes with intense immediacy about the extremely complicated personal and social relationships in her environment,” the Swedish academy that bestows the award wrote. “At the same time as she feels a political involvement, and takes action on that basis, she does not permit this to encroach on her writings. Nevertheless, her literary works, in giving profound insights into the historical process, help to shape this process.”

Though she conceded that it was “nice” to have recognition, she said at the time: “I never thought about the prize when I wrote. Writing is not a horse race.”

She once said she was “not nearly as brave as being a South African has turned out to require” and in another instance described the pain of sitting alone to write while friends from the liberation struggle movement were arrested or had to flee apartheid’s assassins.

“You have to become involved with life, not only in personal relationships but for social causes. But at the same time, you have to stand apart to pursue your writing, to struggle with words to define the whole question of being and existence,” she told an interviewer after winning the Nobel. “They were being tortured and there I was, shutting myself away to write.”

An irony was that her books, extolled overseas particularly after the Nobel Prize win, were not widely read in South Africa, where educationists bemoan the lack of a reading culture. The impoverished, poorly educated black majority didn’t know her work, and some black intellectuals scorned it.

But she hoped her work would remain as a powerful legacy for future generations to discover.

At her best, critics compared her to Jane Austen. At the end of her life, however, her spare, powerful writing style became convulsed with complicated, labored syntax and odd punctuation, reviewers complained.

A South African reviewer wrote of her final book in 2012, “No Time Like the Present, “that her “convoluted stream-of-consciousness writing” was “very rough going.” A Los Angeles Times review noted “outbreaks of an abrupt, careless style, a throbbing undercurrent of arrogance evident in her novelistic methodology.”

The novel’s theme was post-apartheid disappointment with the ANC government; its leader, President Jacob Zuma, and other black liberation struggle figures who came to power only to enrich themselves at the expense of the impoverished population.

She told one interviewer that supporters of the ANC were naïve to believe that everything would change for the better once the liberation movement came to power.

“We were naive, because we focused on removing the apartheid government and never thought deeply enough about what would follow,” she said.

In “No Time Like the Present,” characters experience savage crime and agonize about which schools to send their children to, given the malaise of the education system, considered by some critics to be the ANC’s greatest failure.

Gordimer was herself a victim of violent crime in 2006, when thieves broke into her house in Parktown, one of Johannesburg’s leafy and privileged northern suburbs. The men dragged Gordimer and her female domestic worker upstairs. The domestic worker was punched in the face and the pair were locked in a cupboard while the men ransacked the house.

She later told journalists she felt no fear. She merely reflected that it was her turn to experience the violence that so many South Africans had experienced before.

Another 2006 incident, a row with her biographer, turned into a national polemic on white liberalism, with black critics condemning her insistence that embarrassing details of her life remain private, “thus maintaining her iconic status as a writer of conscience.” Prominent black writer and attorney Christine Qunta wrote that Gordimer’s books were boring and unreadable, describing her as a “white liberal” product of colonialism who was unconsciously racist.

Gordimer ignored the criticism and got on with her writing.

“The best way to be read is posthumously,” she said. “That way it doesn’t matter if you offend a friend or a relative or a lover. It’s absolutely fatal to your writing to think about how your work will be received. It’s a betrayal of whatever talent you have.”

Her first marriage, to Gerald Gavronsky, ended in divorce after three years. She married Reinhold Cassirer, an art dealer and refugee from Nazi Germany, in 1954; he died in 2001. Her survivors include two children, Hugo and Oriane.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.