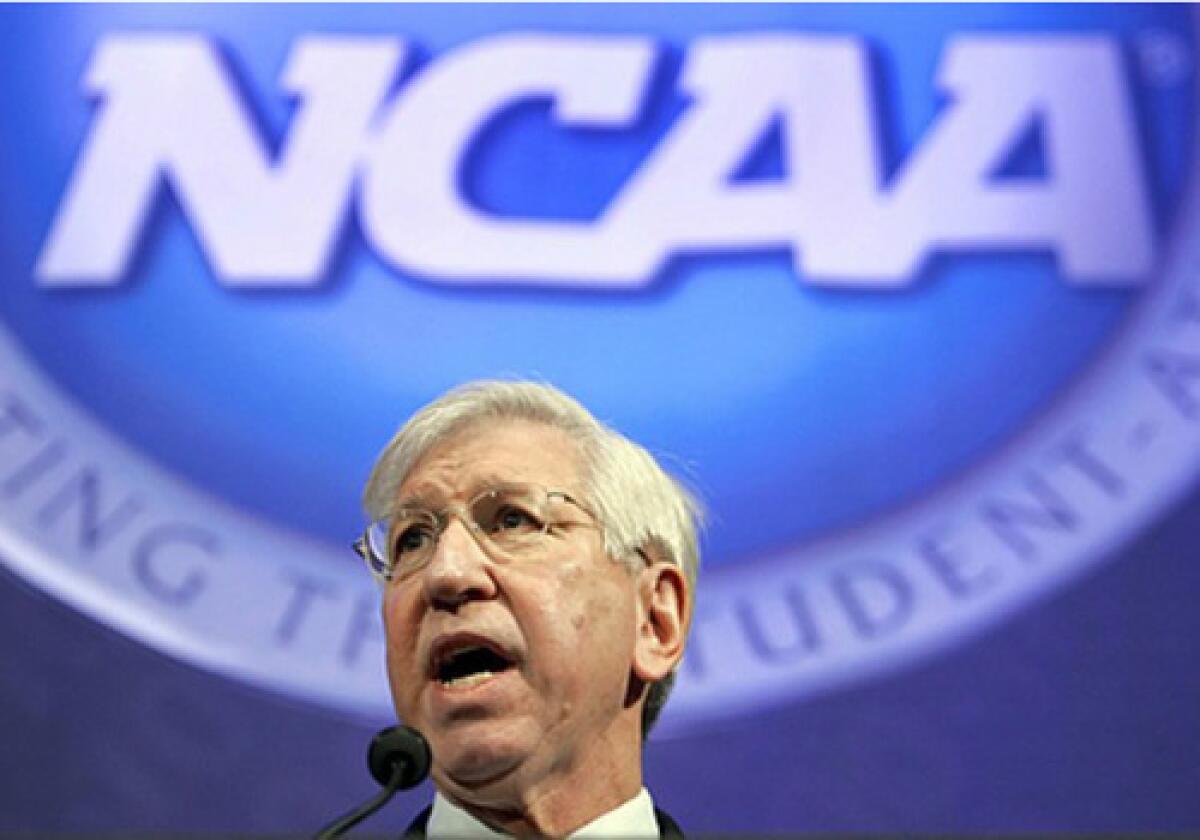

Myles Brand dies at 67; NCAA president

Myles Brand, the NCAA president who is credited with helping to streamline and reform the governing body of collegiate sports but is best remembered as the Indiana University president who fired legendary basketball coach Bob Knight, has died. He was 67.

Brand died Wednesday of pancreatic cancer at his home in Indianapolis, the NCAA announced. He revealed his diagnosis during the 2009 NCAA convention in January outside Washington, D.C.

Brand continued to work during his cancer treatment, saying in a news conference at the 2009 Final Four in Detroit, “the work has actually made it a lot more bearable.”

“Myles Brand was a tireless advocate for the student-athlete,” Michael Adams, president of the University of Georgia and chairman of the NCAA Executive Committee, said in a statement. “Indeed, he worked to ensure that the student was first in the student-athlete model. He will be greatly missed.”

Brand was named the NCAA’s fourth director in 2003, after he had 13 years as a university president. He was president at the University of Oregon from 1989 to 1994 and then at Indiana from 1994 through 2002.

As president of the Bloomington, Ind., university, Brand drew national headlines when, in September 2000, he fired Knight, one of the most successful and controversial coaches in college basketball history.

In 29 seasons at Indiana, Knight had led the Hoosiers to three national titles while running a program acclaimed for its high graduation rate and intolerance of NCAA rule-breaking.

Yet Knight’s fiery temper and domineering personality led to frequent run-ins with officials, players and administrators.

Brand took a stand in May 2000 when he put Knight on notice after footage showed the coach seemingly putting a brief chokehold on one his players, Neil Reed, at a 1997 practice.

Instead of firing Knight, Brand imposed a “zero tolerance” edict on the coach, warning that any further incidents would lead to immediate termination. Brand also fined Knight $30,000 and suspended him for three games.

Knight accepted Brand’s terms, but the peace wouldn’t last.

Less than four months later, on Sept. 10, after Indiana student Kent Harvey accused Knight of grabbing his arm during a hallway confrontation, Brand fired the coach.

The incident occurred after Harvey reportedly greeted the coach with “Hey, Knight, what’s up?”

Knight said he stopped Harvey only to give him a lesson on manners.

Brand called Knight’s continuing behavior “defiant and hostile” and in violation of the “zero tolerance” agreement.

“Unquestionably, this is the most difficult decision I’ve ever had to make,” Brand said at the news conference announcing Knight’s firing. “Bob Knight is a legendary coach at a school with a legendary basketball program.”

The news made national headlines and infuriated many. Brand and his wife, Peg, a professor of philosophy and gender studies, were forced to temporarily leave the campus’ presidential house after 2,000 students protested and burned Brand in effigy.

Brand argued that Knight’s larger-than-life persona gave the false impression that the university was obsessed with athletics. He told the Indianapolis Star that the role of athletics is “important but not the central role of the university” and that Knight’s firing could serve as a “teachable moment.”

Knight disputed the school’s findings regarding the Harvey incident and said he thought Brand set him up by invoking the “zero tolerance” policy that was almost impossible to adhere to.

Brand did not second-guess himself about initially allowing Knight to remain as coach.

“That was the ethical and moral thing to do,” Brand said at the time. “Coach Knight has contributed almost 30 years to this university and has been successful in many ways. I believed then and continue to believe we had to give him one last chance.”

Knight returned to coaching in 2001 at Texas Tech, where he eclipsed North Carolina Coach Dean Smith’s all-time record of 879 major college basketball victories. He retired from Texas Tech in 2008 with a record 902 victories.

Brand was born May 17, 1942, in Brooklyn, New York, and earned a bachelor’s degree in philosophy at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in 1964, before receiving his doctorate in philosophy from the University of Rochester.

After he was named to lead the NCAA, Brand quickly moved to make the organization, often criticized for its bureaucracy, more user-friendly.

The first sitting university president to ascend to the NCAA’s top executive position, Brand’s most notable program, “Academic Progress Rates,” held athletic departments publicly accountable for scholastic performance.

Schools that fell short were punished with the loss of athletic scholarships.

“That’s the only way to put teeth into reform,” he said in 2003.

Brand also worked to get university presidents more involved in policymaking and was generally seen as more sympathetic to athletes’ eligibility issues.

Brand had no power to change bylaws, but he helped shape policy and steer legislation toward enactment.

“I know I sound a little old-fashioned,” he once said, “but I believe one of the biggest advantages in this position is the bully pulpit, and I want to raise the value of intercollegiate athletics.”

The Times noted of Brand in 2006 that he moved the NCAA “into a more nimble organization.”

Greg Shaheen, the NCAA’s vice president of Division I men’s basketball, told The Times in 2006 that Brand’s management style profoundly changed how the NCAA functioned.

“He’s a trained philosopher,” Shaheen said. “He thinks through things until he’s heard what he needs to make a decision. He doesn’t relive it. He doesn’t re-digest.

“It has led to decisive action and led to an understanding within the organization that we’re going to make decisions, do the right thing and not feel that change is going to take years.”

Besides his wife, Brand is survived by a son, Joshua.

The Times noted of Brand in 2006

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.