Muhammad Ali dies at 74; boxing champion became worldwide celebrity

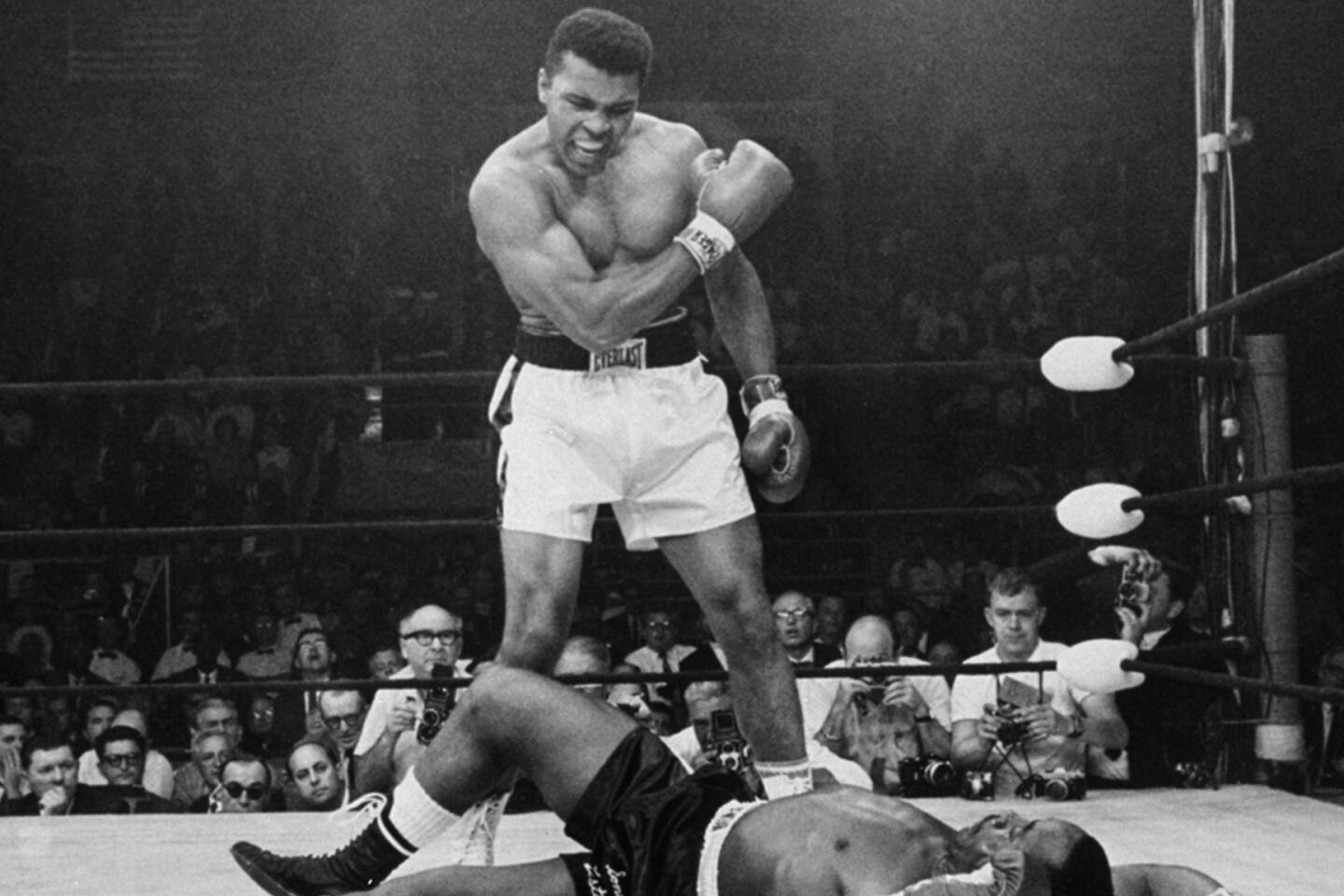

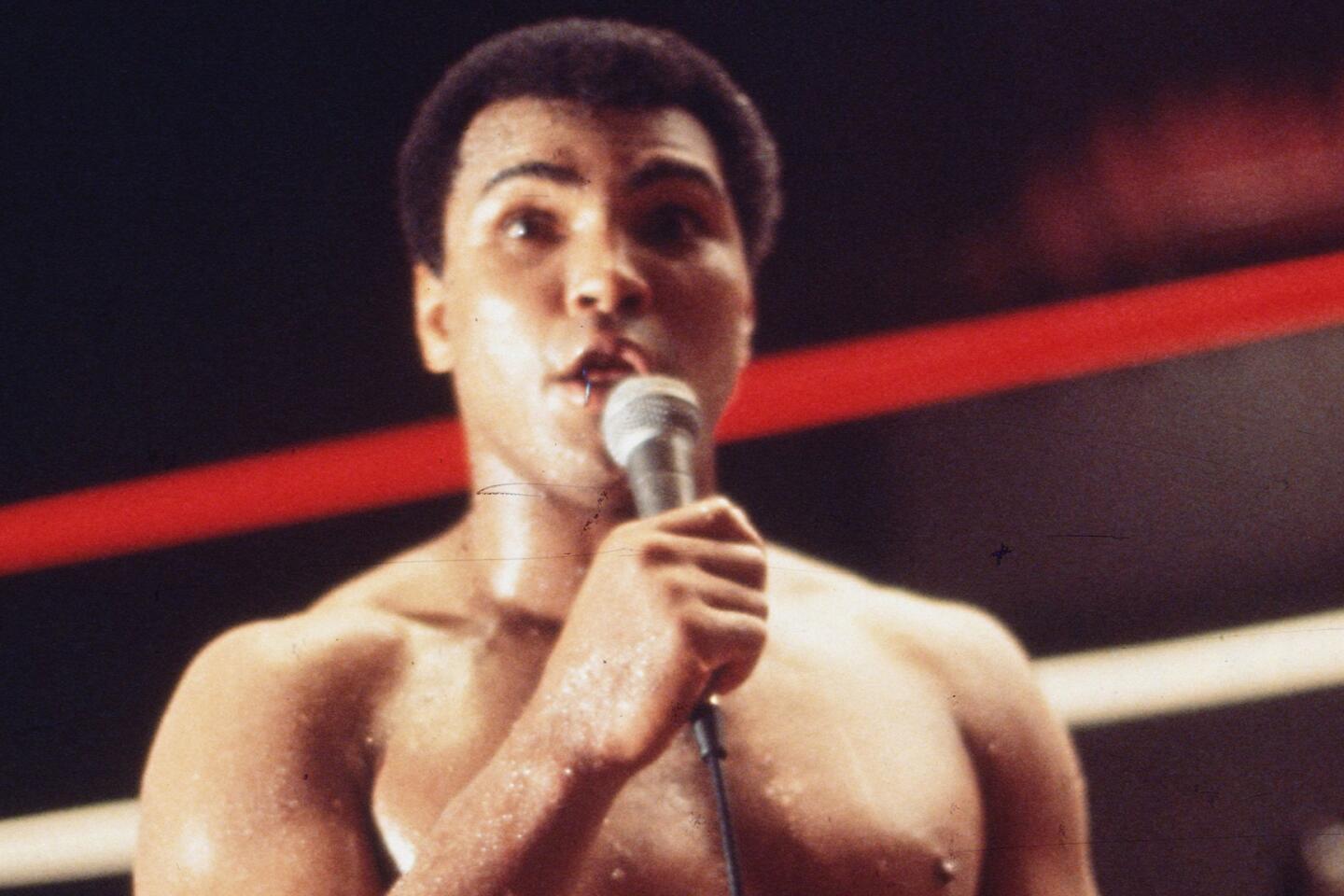

After defeating Sonny Liston in 1964, an ecstatic Muhammad Ali declared: “I shocked the world.”

Thrusting his arms into the air, he treated the victory as if it had been a knockout. Never mind that Liston denied him that honor by refusing to step into the ring for a seventh round. Ali’s win gave America a first glimpse of the young man who for the next 50 years would never stop shocking the world.

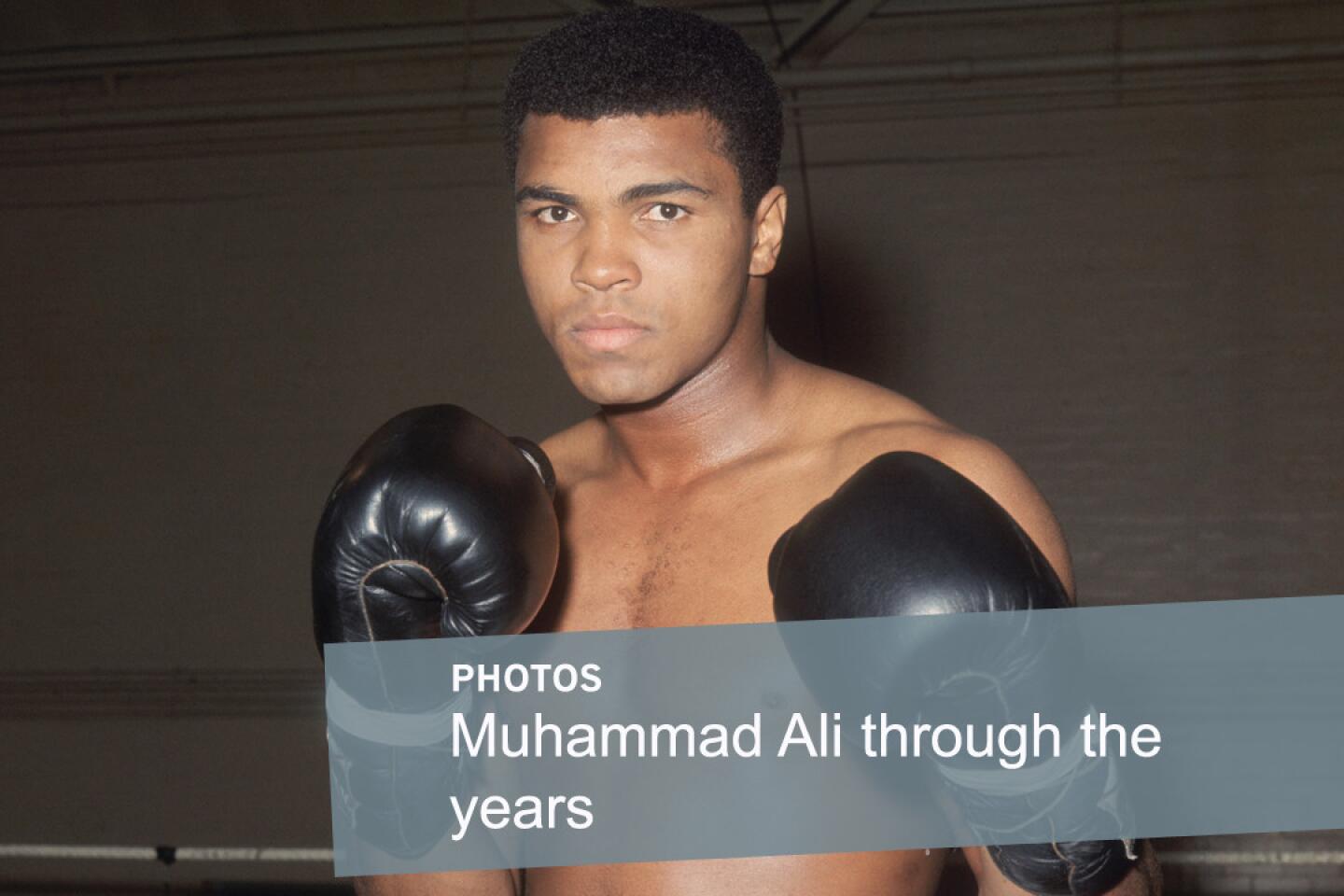

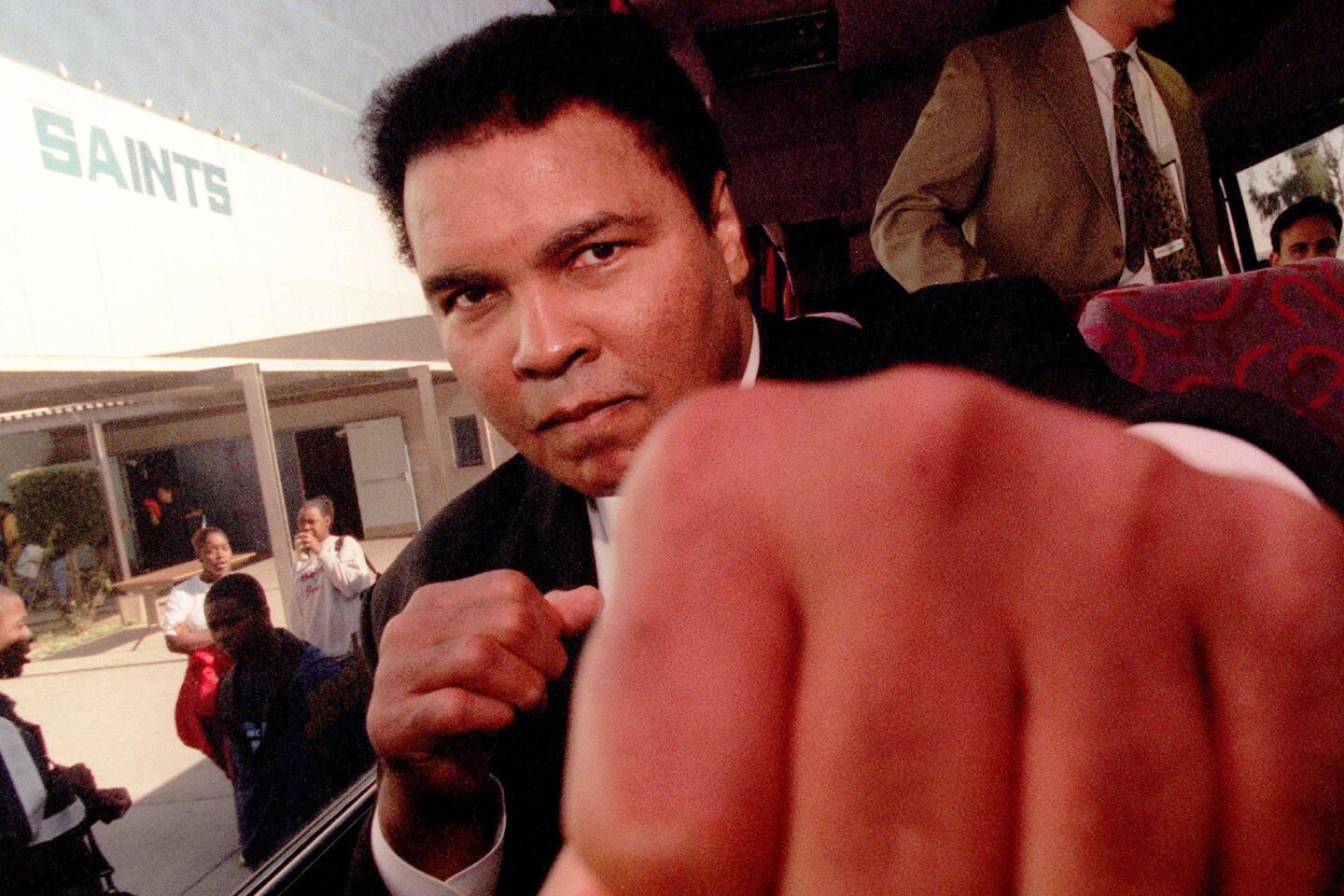

Ali, the brash and ebullient heavyweight boxer whose brilliance in the ring and bravado outside it made his face one of the most recognizable in the world, has died, according to a statement released by his family. He was 74. Ali had suffered from Parkinson’s syndrome for many years.

If Jesse Owens and Jackie Robinson opened the door for black athletes, Ali stormed through, making sure it would never close again. His celebrity transcended race and sports, for as dexterous as he was in the ring, he was equally skilled at challenging the status quo. Guided by his religion, bolstered by his popularity, he tempered his righteousness with an ever-quotable wit and a prevailing sense of cool.

Grandson of a slave, he was feted by presidents and kings. He defeated the Justice Department in the Supreme Court, worked as a humanitarian and an ambassador and became a hero to those who watched him light the Olympic flame in Atlanta in 1996, his body shaking with the emotion of the moment and the symptoms of the disease that had stolen his strength.

Since retiring from the ring in 1981, he lived with the tremors, slowness in gait and slurring of speech of Parkinson’s syndrome, which doctors attributed to the poundings he endured in the late stages of his career when he could no longer feint and dance his way out of harm’s way.

Yet even as he grew weaker he maintained a public profile. One of his last appearances came during the opening ceremony of the 2012 Summer Olympics in London.

“Ali was the great artist of the ring — in his prime an extraordinary combination of skill, swiftness, ingenuity and cunning as well as a sardonic playfulness and audacity not seen in boxing since Jack Johnson,” boxing aficionado and novelist Joyce Carol Oates told The Times in 2013.

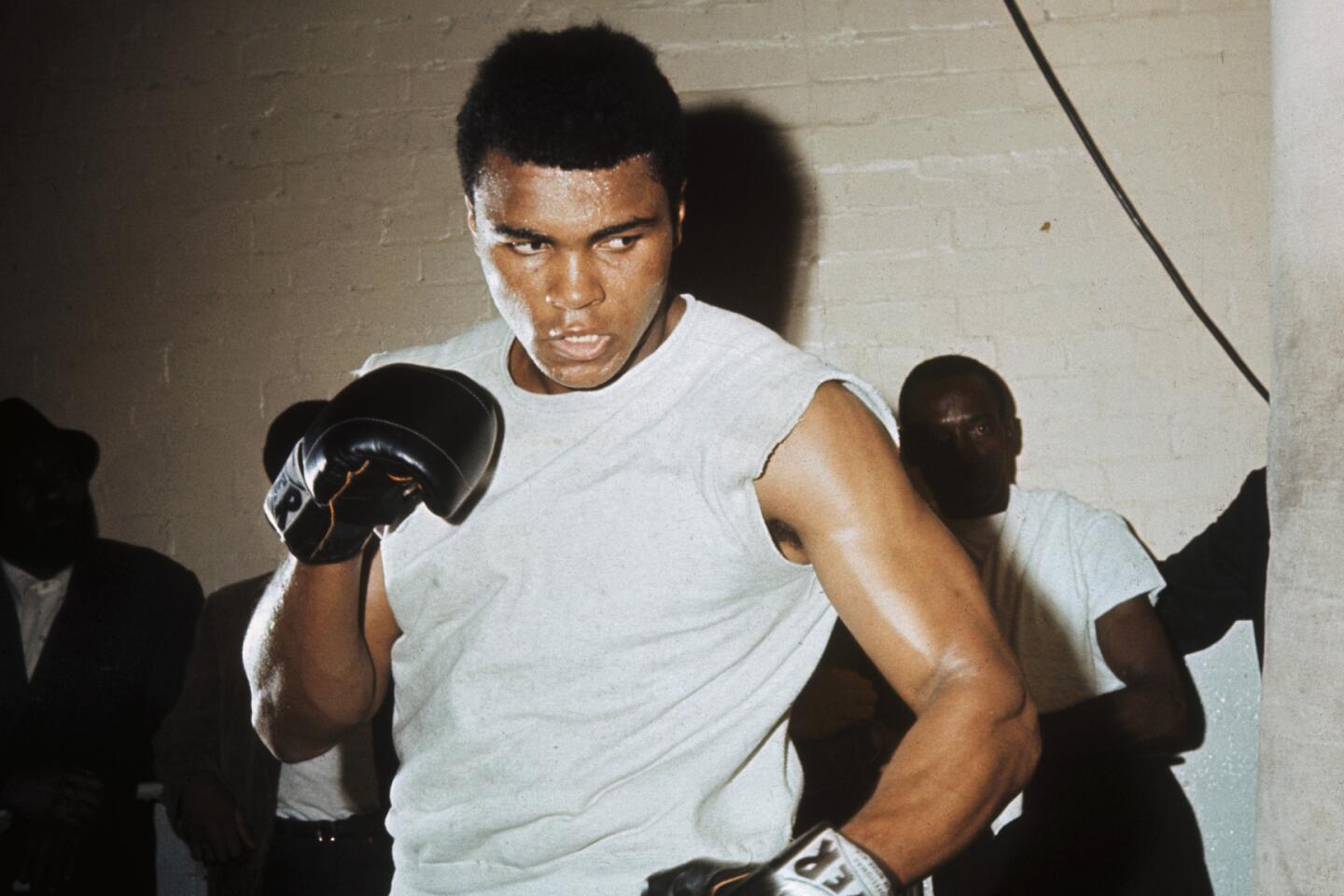

Inside the ring, Ali was a fighter who early in his career was known as Cassius Clay, and even though he held his hands too low and his punches were often glancing, he bettered opponents with his tenacity and versatility. In his long career, he lost only five professional fights, and two of those were after he came out of retirement.

Outside the ring, he was a rebel who never backed down from his principles.

The day after he defeated Liston, he announced that he was a member of the Nation of Islam, and a few weeks later he adopted a Muslim name.

“Cassius Clay is a slave name,” he said. “I didn’t choose it and I don’t want it. I am Muhammad Ali, a free name — it means ‘beloved of God’ — and I insist people use it when people speak to me and of me.”

The day he was classified as eligible for the Vietnam draft in 1966, he voiced his opposition to the war.

“I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong,” he famously told the gathered reporters.

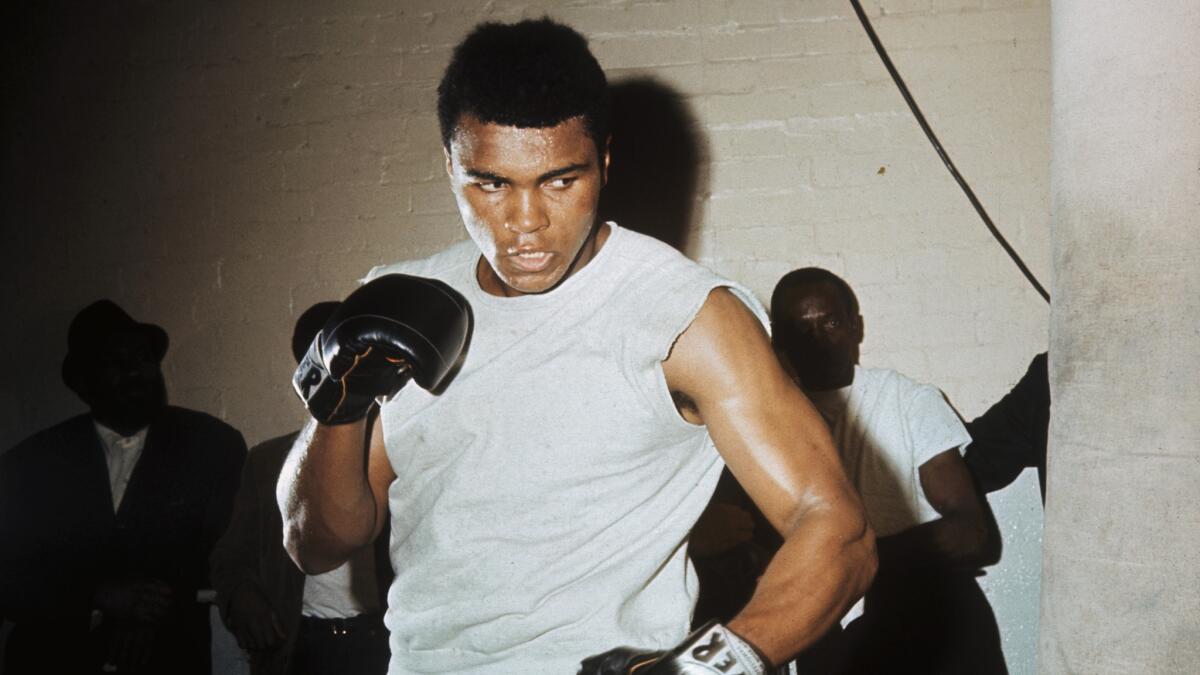

Brash, forthright and blunt, Ali never once doubted his worth and often expressed it with humor and style. Describing his steps in the ring, he delighted the media with doggerel. “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee,” he said, borrowing lines coined by one of his trainers. “Your hands can’t hit what your eyes can’t see.”

He turned bragging into an art form. “I’m so mean I make medicine sick,” he quipped, and “I’m so fast that last night I turned off the light switch in my hotel room and was in bed before the room was dark.”

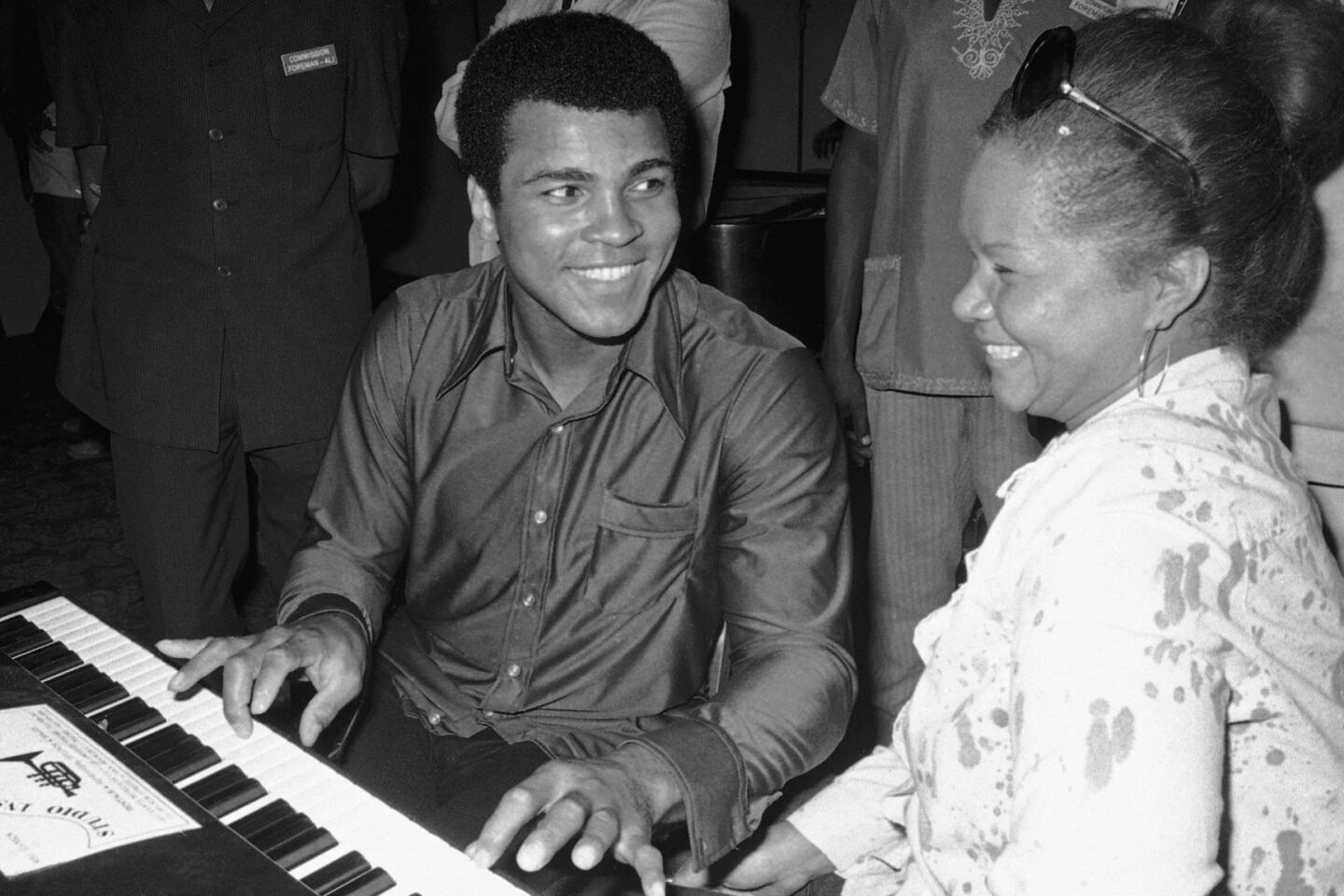

He understood the value of showmanship and humor. A few days before his bout with Liston, the Beatles — visiting Miami for a taping of “The Ed Sullivan Show” — stopped by the training gym. Photographers captured Ali tapping George Harrison with a punch that connected, domino-style, with the other three band members.

Throughout his career, Ali inspired some of the finest journalists — A.J. Liebling, Norman Mailer, George Plimpton, David Remnick — to put words to his charisma.

“He became so famous that in his travels around the world Ali could gaze out of airplane windows — down at Lagos and L.A., down at Paris and Madras — and be assured that almost everyone alive knew who he was,” Remnick wrote in “King of the World,” published in 1998.

Sports Illustrated writer William Nack described Ali’s life as “so brassy and daring, so filled with wonders and adventure and so enlarged by the magic of his personality and the play of his mind, that no one remotely like him has ever been seen on the sporting scene.”

Superlatives and hyperbole came to define him, and he was happy to let the claims stand unchallenged.

::

Muhammad Ali was born Jan. 17, 1942, in Louisville, Ky. He was named after his father, Cassius Clay, who in turn had been named after a 19th century white abolitionist.

Cassius Sr. was a sign painter and occasional muralist. Ali’s mother, Odessa Grady Clay, was a domestic and cook. Nicknamed GG by his mother, Ali was a child who made jokes and enjoyed being the center of attention. The family attended Mount Zion Baptist Church.

When asked how he started boxing, Ali often told the story about the time his bike was stolen. He was 12 and had ridden to Louisville’s Columbia Auditorium, where popcorn and ice cream were being handed out.

Leaving the hall, he discovered his $60 red-and-white Schwinn missing. He reported the theft to an off-duty policeman who ran a boxing gym. Ali said he wanted to “whup whoever stole it.”

The policeman invited him to start coming to the gym. Ali impressed his trainer not just with his speed and strength but with his discipline: When hit hard, he neither panicked nor got angry.

When not at the gym, Ali traded punches with his brother Rudy and his friends behind Leonard Tucker’s grocery store. In the mornings, he jogged the streets of Louisville, wearing heavy steel-toed work boots.

Growing up in the Jim Crow South, Ali knew about the two Americas, the one for whites and the one for blacks. He was 13 when the mutilated body of a black boy, Emmett Till, was retrieved from a Mississippi river and an all-white jury acquitted the white killers in just 67 minutes.

The injustice affirmed the role that boxing would play in his life. “I started boxing because I thought this was the fastest way for a black person to make it in this country,” he said.

He honed his skills as an amateur and in 1960 won the gold medal in the light heavyweight division at the Rome Summer Olympics, a debut he almost missed because of his fear of airplanes (he bought a parachute for the trip).

When a Russian journalist asked how he felt about winning a medal for a country where restaurants refused to serve him, Clay shot back: “Tell your readers we got qualified people working on that problem, and I’m not worried about the outcome. To me, the U.S.A. is the best country in the world, counting yours.”

That medal took on legendary status when Ali claimed in his 1975 autobiography, “The Greatest,” that he threw it into the Ohio River after being denied service at a restaurant. Later he said that he had simply lost it.

After turning professional, Ali was backed by a consortium of 11 Kentucky millionaires who offered him one of the most lucrative contracts in boxing history. His first professional match — he trained by sparring with his brother — took place on Oct. 29, 1960, a victory that came with a $2,000 purse.

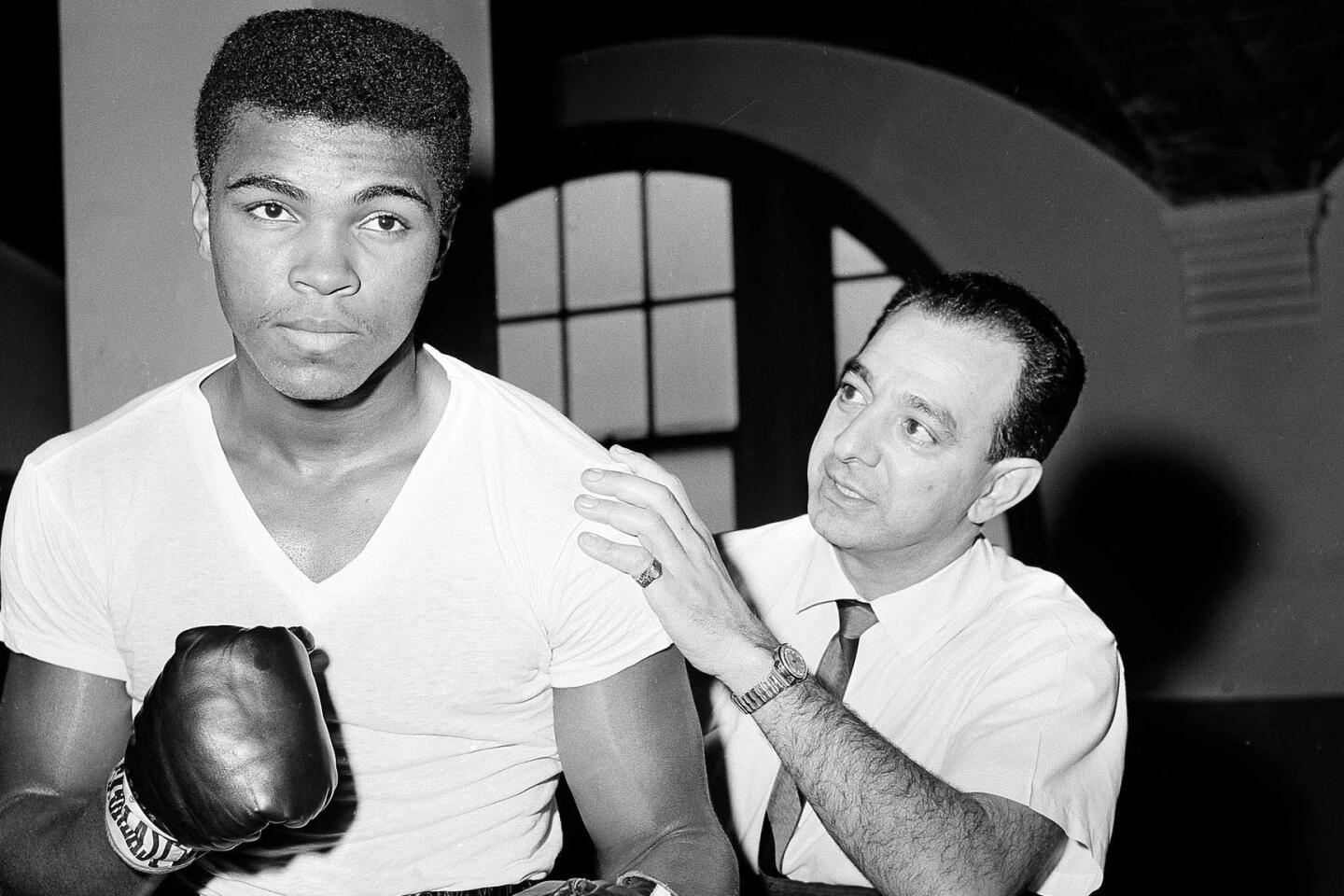

Afterward, Ali’s backers persuaded Angelo Dundee to become his personal trainer, and Ali moved to Miami to work out at Dundee’s Fifth Street Gym. Their relationship lasted until the fighter’s retirement 21 years later.

Ali never underestimated the power of self-promotion. One of his first lessons, he said, came in Las Vegas in 1961 when he met George Wagner, also known as Gorgeous George, a wrestler who never shied from the opportunity to call himself the greatest in his sport.

I started boxing because I thought this was the fastest way for a black person to make it in this country.

— Muhammad Ali

Dubbed Gaseous Cassius and the Louisville Lip, Ali worked the spotlight and once explained to Sports Illustrated the differences between other boxers and him. “I’ll break the news to you,” he said, “you never heard of them.”

During the 1963 newspaper strike in New York City, Ali took to the streets to promote a fight at Madison Square Garden, and that year he recorded a spoken-word album, “I Am the Greatest!” Poet Marianne Moore wrote the liner notes.

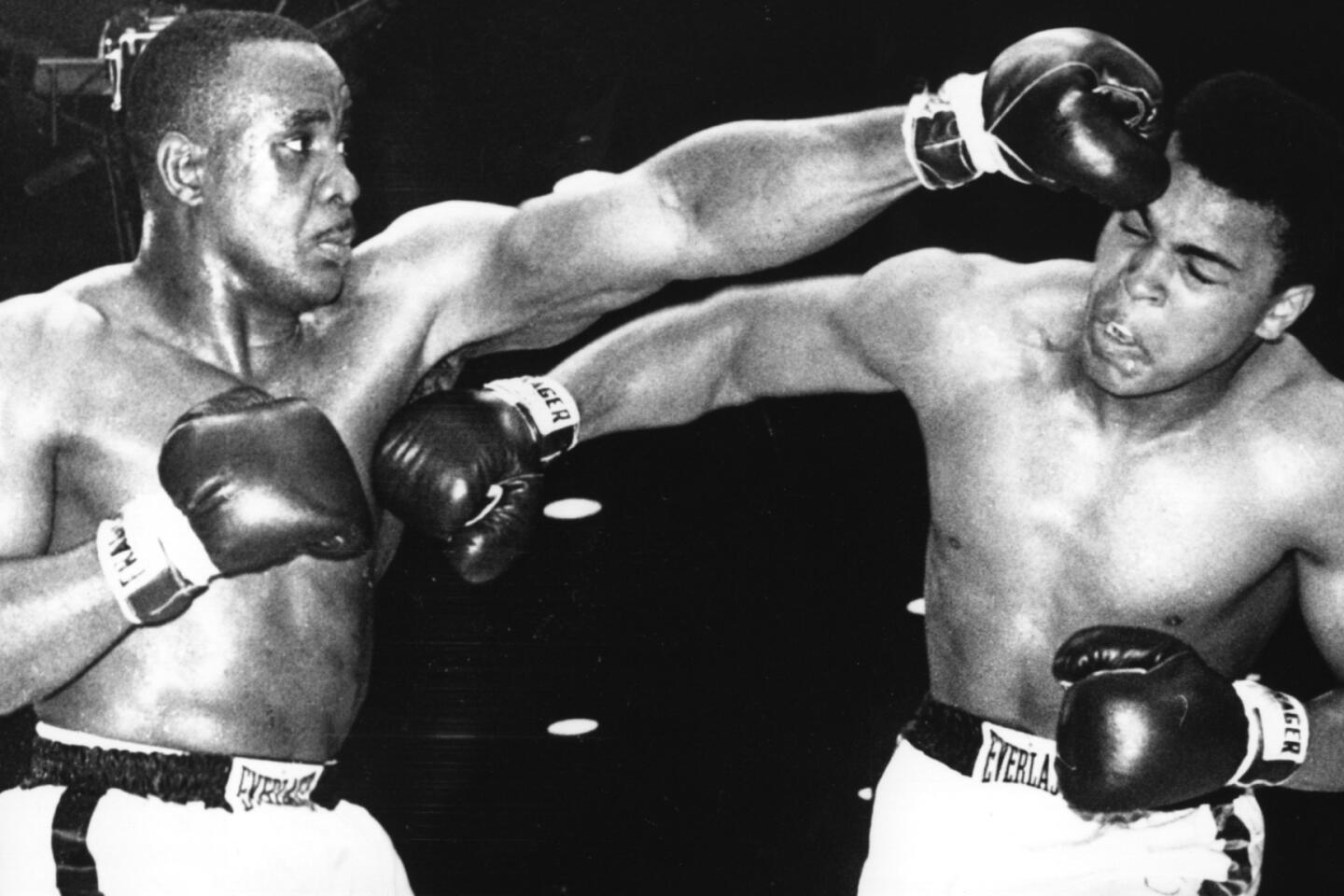

Before the Liston bout in 1964, Ali had won 20 professional fights (including a 1962 debut in Los Angeles at the Sports Arena), but sportswriters doubted him. He was 22, a 7-to-1 underdog whom no one expected to last three minutes in the ring against the Big Bear.

When the bell rang, he went about “running and slipping,” as one reporter wrote, “like someone killing time in a pool hall.”

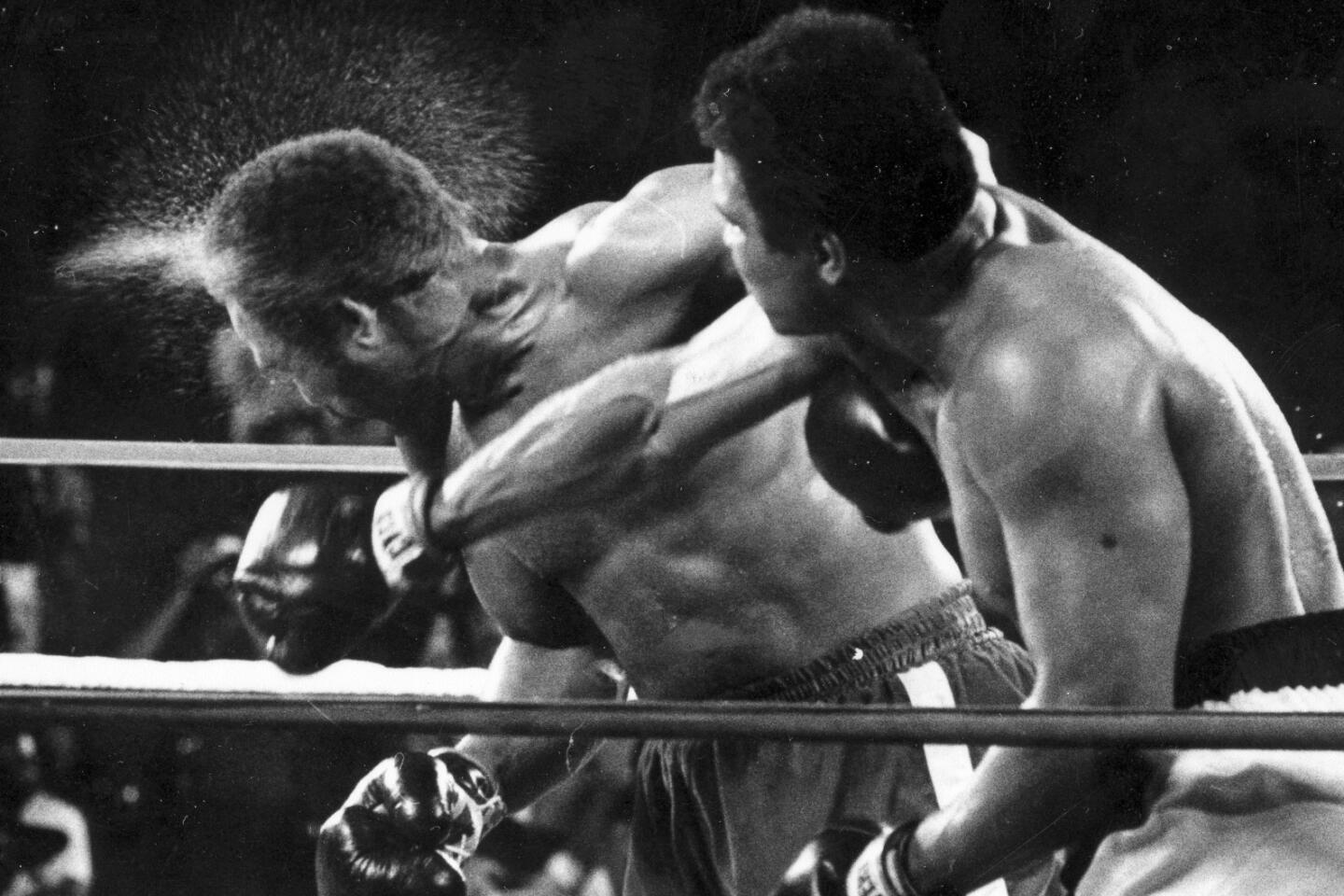

By the third round, he began to hit Liston with eye-blurring combinations that became his trademark. Momentarily blinded in the midst of the fight, Ali staggered, then regained his footing, taking Liston apart with left hooks and right uppercuts.

After those seven rounds, the world was a different place for him.

On a trip to Africa later that year, he was greeted as an international star. When he returned, he starting going out with a cocktail waitress, Sonji Roi. Thirty-two days later, they married.

Ali found himself defending his affiliation with the Nation of Islam. He had been intrigued with the sect since high school and knew that it was perceived as having a radical separatist agenda. His public stance — in the company of Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad — created a rift in his family and polarized fans.

Moderate blacks believed the Nation of Islam’s agenda too extreme for the civil rights struggle. They worried that the sect was taking advantage of Ali because of his celebrity status. Still they admired him for his confidence and pride, and how he disparaged the word “Negro” and wore his hair full.

“The act of joining was not something many of us particularly liked,” civil rights leader Julian Bond told the writer Thomas Hauser. “But the notion he’d do it; that he’d jump out there, join this group that was so despised by mainstream America, and be proud of it, sent a little thrill through you.”

“He was able to tell white folks for us to go to hell; that I’m going to do it my way,” comedian Dick Gregory told Hauser.

Ali denied that his beliefs were a passing trend. “A rooster crows only when it sees the light,” he told reporters. “Put him in the dark, and he’ll never crow. I have seen the light, and I’m crowing.”

Ali’s popularity grew when he refused to be inducted into the Army to fight in Vietnam. He said he was exempt because he was a minister for the Nation of Islam, but he also used race to argue his point.

“Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-call Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs,” he told Sports Illustrated.

Sportswriters denounced him as a traitor, as did the Kentucky Legislature, and the FBI subjected him to the same surveillance as Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

On June 20, 1967, Ali was convicted of violating the Selective Service Act, sentenced to five years in prison and fined $10,000. His boxing license was revoked, and he was stripped of his titles. As the case was appealed, he lectured on college campuses where he was greeted as a hero for being willing to sacrifice his income and stature in opposition to the war.

“I put him in the same category as Nelson Mandela, who stood up for a whole lot of folks by just staying where he was and saying what he believed in,” the late musician Gil Scott-Heron once said.

During this time, Ali divorced Roi and had their marriage annulled on the grounds that she failed to uphold Islamic beliefs. His next marriage to 17-year-old Belinda Boyd was arranged by her Muslim parents. He had met Boyd at her school, and after the wedding she adopted an Islamic name, Khalilah Ali. The couple had four children.

In 1970, the New York State Athletic Commission reinstated Ali’s license, and after a three-year hiatus he took on new fighters, most notably Joe Frazier in Madison Square Garden. Although both fighters were black, Ali expressed a disdain for Frazier that seemed to go beyond the usual taunts. “Anybody black who thinks Frazier can whup me is an Uncle Tom,” he said.

In the end, Frazier knocked Ali down and won by unanimous decision, marking Ali’s first loss as a professional.

Three months later, on June 28, 1971, Ali won a unanimous decision against the Justice Department in the U.S. Supreme Court. The charges of draft evasion were dropped, and for Ali, some of his best — and most brutal — fights lay ahead.

::

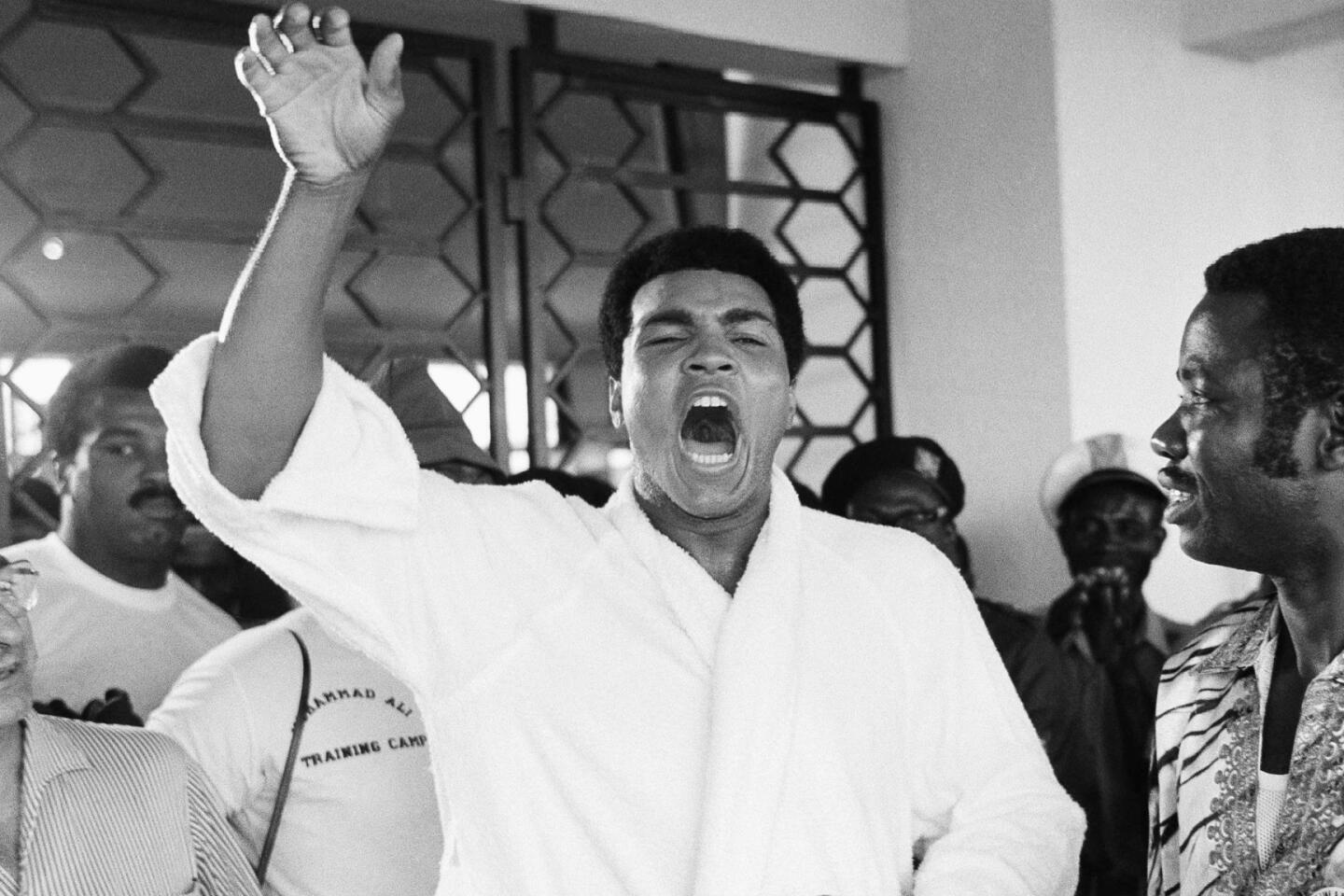

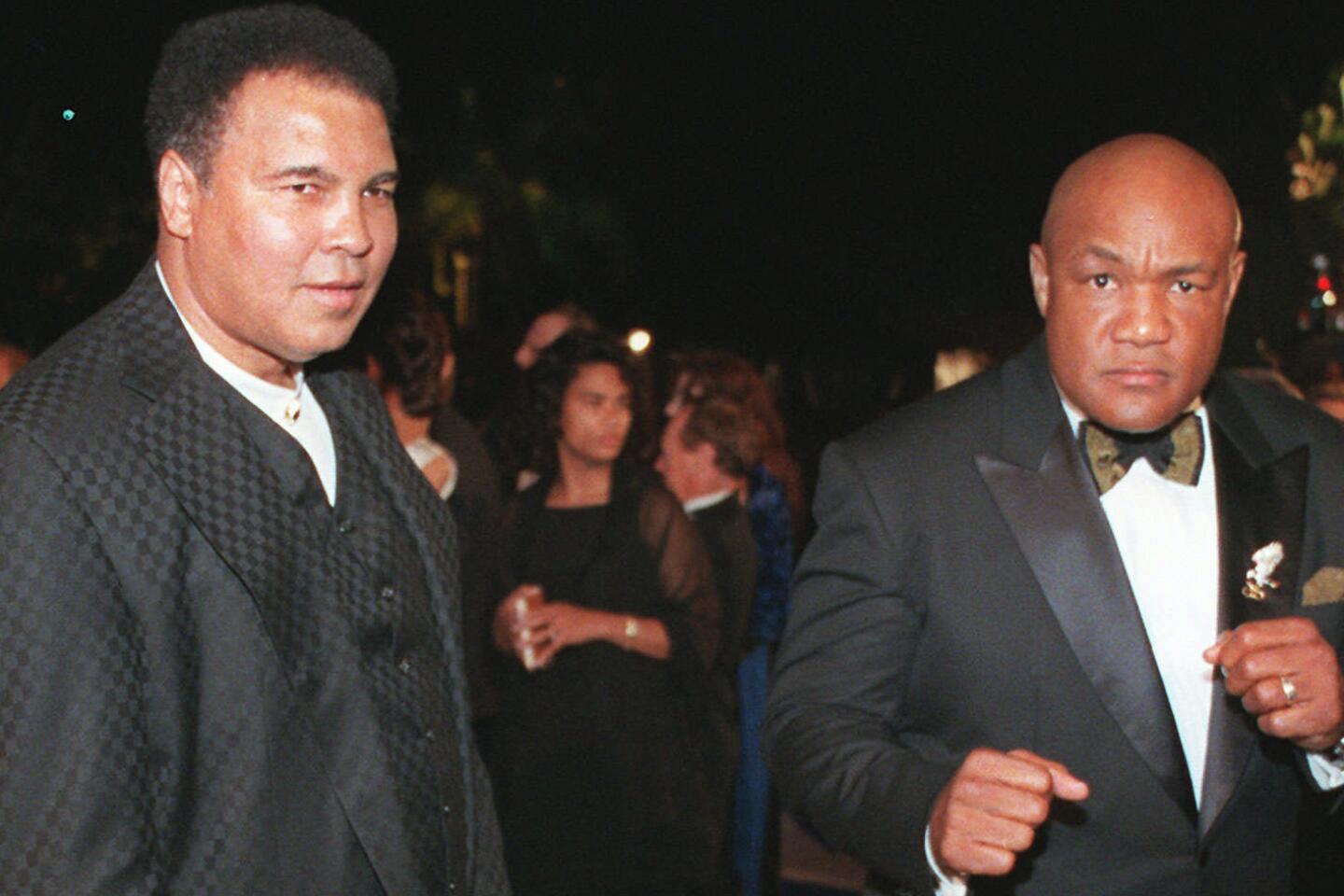

With no title to his name, Ali began a comeback that led to his 1974 match-up against heavyweight champion George Foreman.

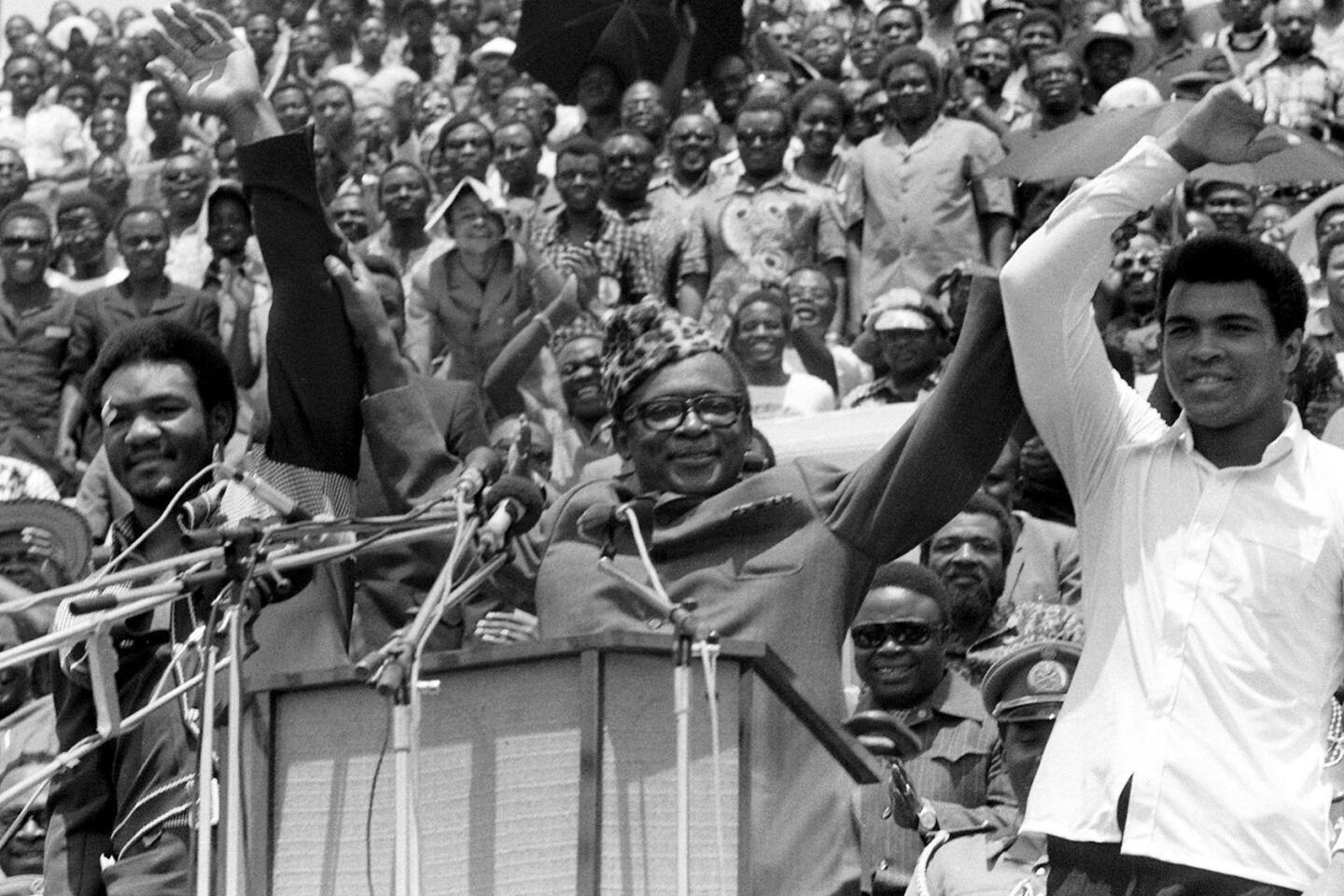

Billed as the “Rumble in the Jungle,” the fight was held in Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) and promoted by Don King, who arranged for the Zairian president to put up $5 million for each fighter, at the time the biggest payday in sports.

Arriving months earlier to train, Ali was never without an entourage, which came to include the crowds that followed him. The fight itself drew 60,000 spectators and millions of pay-per-view customers.

During the match, Ali stunned fans by allowing Foreman to pummel him in what became known as his “rope-a-dope” tactic. Ali had realized that in the heat he would not be able to dance and bob as planned. He hoped instead that the hard-punching Foreman would wear himself out.

In the eighth round, Ali delivered a blow that sent Foreman spinning around and down onto the canvas.

It was only the second time since Floyd Patterson that a heavyweight had regained the title.

A year later, Ali went up against Frazier for their final contest in what came to be known as the “Thrilla in Manila.”

Days before the fight, Ali created a public scene when he introduced Veronica Porsche, a former L.A. beauty queen who had traveled with him since the fight in Zaire, as his wife. Upon hearing this, Belinda flew from Chicago to Manila. Their argument in the hotel was loud and public. They divorced in 1977.

More than a fight, the bout with Frazier was a grudge match, and not until the end of the 14th round — with the fight evenly scored at 63-63 — did Frazier’s trainer concede. Frazier’s left eye was closed, his right eye was closing and he was spitting blood. Still, his punches — 440 hits — took a toll on Ali.

“If dying is that hard,” Ali said, “I’d hate to see it coming.”

Three years later, Ali lost his crown to Leon Spinks, a fighter 12 years his junior. Ali tried the rope-a-dope tactic, but he couldn’t pull it off. Seven months later, Ali won the rematch, earning the heavyweight title for the third time.

“I’d be a fool to fight again,” Ali said in 1979. But, still attracted to the money and glory of the ring, he agreed to two more bouts. He lost both, and in 1981 he hung up his gloves for good.

He was married at the time to Porsche. The couple had two daughters, including Laila Ali, who had a career as a professional boxer.

Ali’s diagnosis of Parkinson’s did not come as a surprise. His doctors had seen his deteriorating condition for years. It was especially cruel for a fighter who had worked hard to leave the sport without a broken nose or the cauliflower ears that disfigured other boxers.

Retirement was difficult for Ali. He hadn’t managed his earnings well. During one of his final fights, which carried an $8-million purse, he paid a third to his manager and $1 million to the promoter. Almost all of the rest went to taxes and training expenses.

Some estimates put his daily expenses at the time at $10,000, money that went to his properties in Pennsylvania, Michigan, Chicago and Los Angeles; to the Nation of Islam; to child support and alimony; and to his retinue.

In 1981, he was embarrassed by an embezzlement scheme involving a company he had endorsed. He also hired as his attorney Richard Hirschfeld, who would be convicted of securities violations. Ali was not implicated, but the associations suggested greater problems in his camp.

In 1985, he divorced Porsche and a year later married his fourth wife, Yolanda “Lonnie” Williams, whom he had known since childhood. They adopted a child, and together they slowly rebuilt his reputation.

Ali turned his attention to fundraising for charity and medical research. He converted his boxing camp in Pennsylvania into a home for abused children.

In 1985, he traveled to the Middle East on an unsuccessful trip to seek the release of four Americans and a Saudi diplomat held hostage in Lebanon. In 1990, he traveled to Iraq and won the freedom of 14 American hostages held by Saddam Hussein.

He was able to tell white folks for us to go to hell; that I’m going to do it my way.

— Comedian Dick Gregory

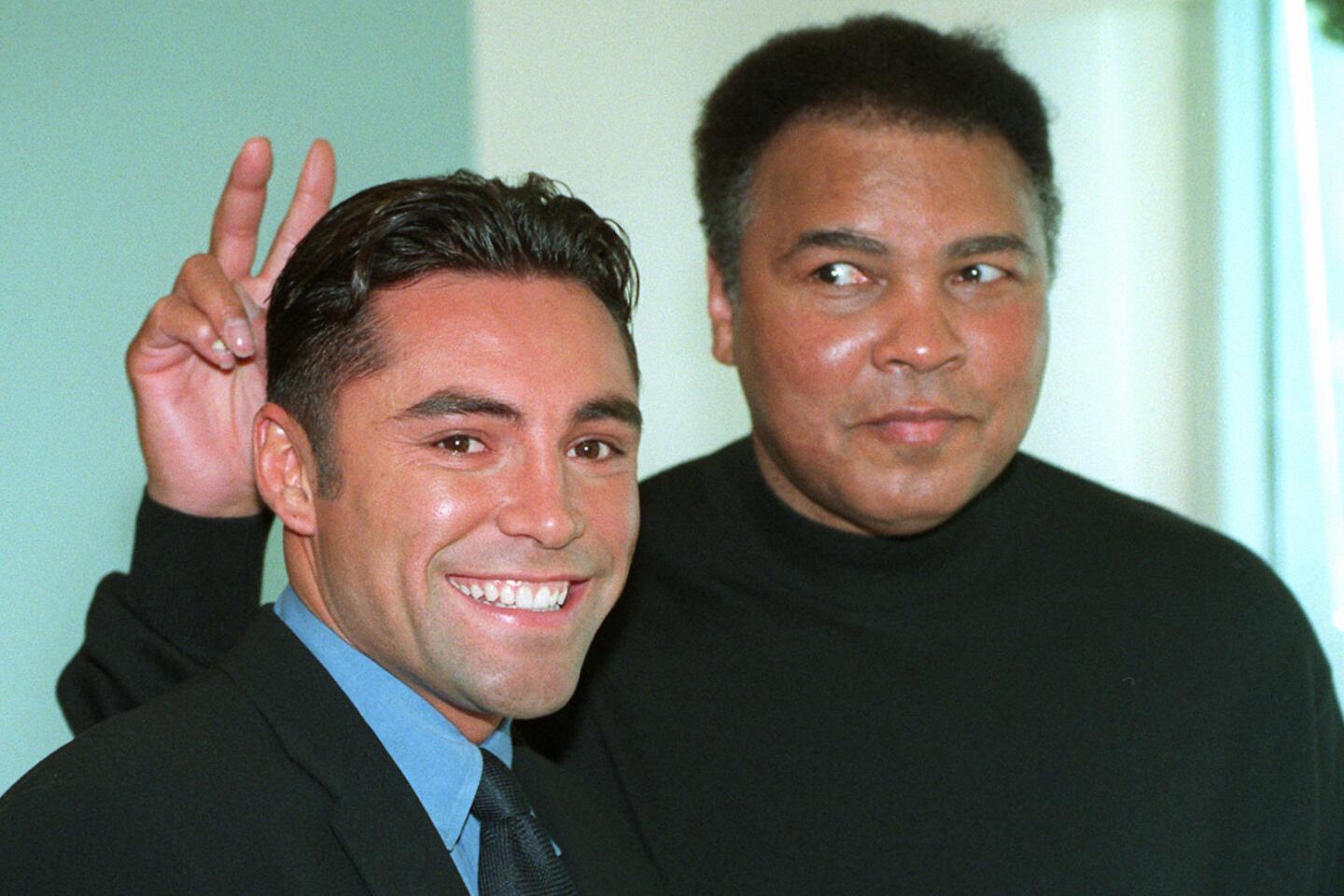

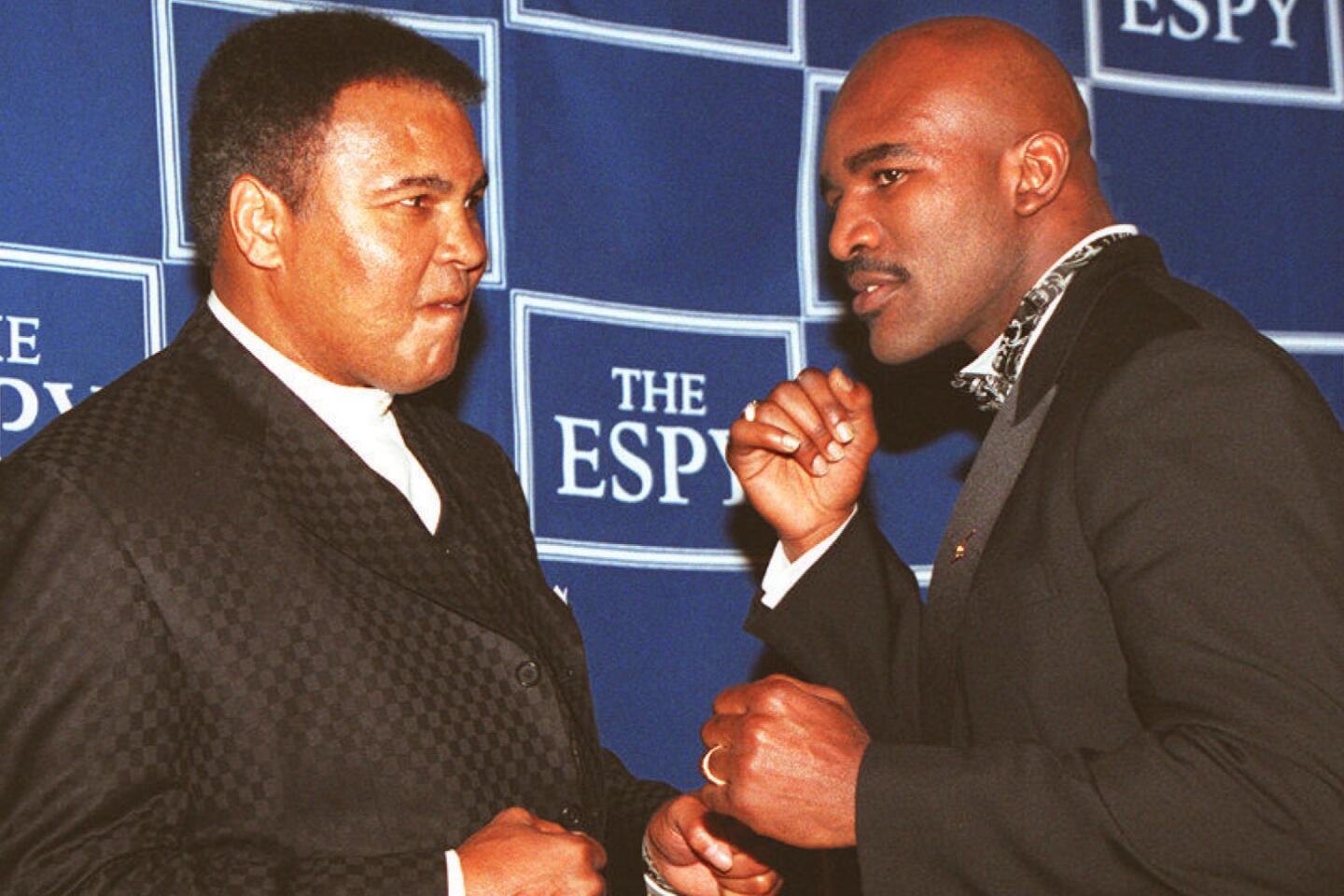

In 1996, he stepped out of isolation and stood before 83,000 spectators to light the Olympic flame in Atlanta. Three months later, “When We Were Kings,” the documentary of his fight against Foreman in Zaire, was released, and at the Academy Awards he received a standing ovation.

He was profiled in a segment on “60 Minutes.” A number of books helped frame his straight-talking wisdom, including an authorized biography and two memoirs.

In 2005, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian award, from President George W. Bush, who called Ali “the greatest of all time.” Later in the year, Ali presided over the opening of the $80-million Muhammad Ali Center, an education and cultural complex in Louisville.

In 2006, a New York entertainment company, CKX Inc., paid him and Lonnie $50 million for the commercial rights to the name and likeness of the boxer.

In his daily life, Ali, a devout Muslim, would pray five times daily and study Islamic texts. He once said that he received 12,000 letters a week, and he wrote up to 40 letters a day.

He recently moved from Michigan to Arizona, and though the world may have pitied his decline, he never gave it much thought.

“I know why this happened,” Ali told Remnick. “God’s showing me that I’m just a man like everyone else. Showing you, too. You can learn from me that way,” he said.

He is survived by his wife, Yolanda; his brother, Rahman Ali; seven children from three wives; and two children from two women he never married.

Kennedy is a former Times staff writer. Former Times staff writer Steve Springer contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.