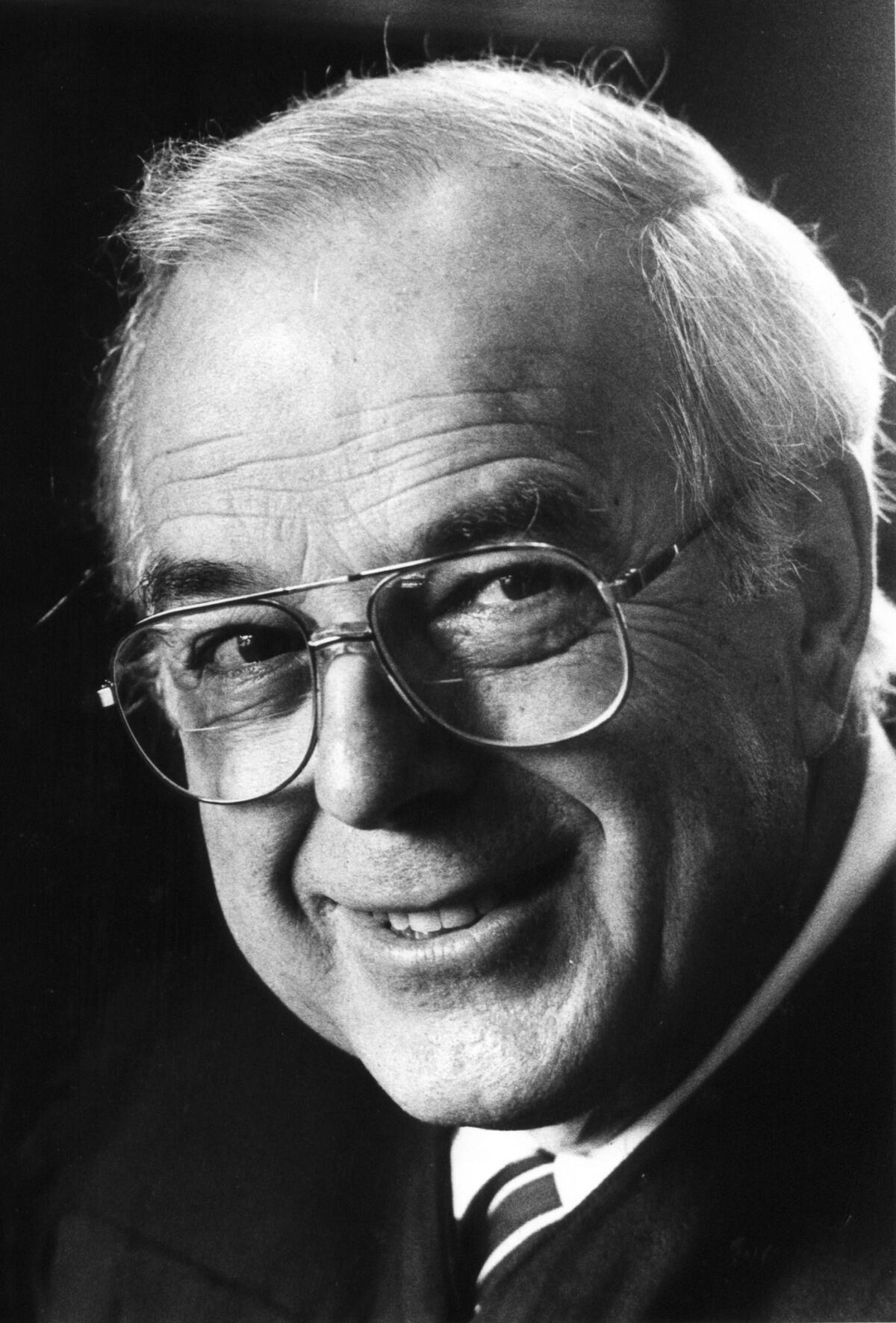

Manuel L. Real, judge who helped desegregate Southern California schools, dies at 95

Manuel L. Real, a towering legal figure who ordered the desegregation of a prominent Los Angeles County school district and approved an unpopular but mandatory busing plan to achieve integration in the classroom, has died. He was 95.

Real, who died Wednesday , was the nation’s longest-serving active federal judge. His death was announced by the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California.

The jurist’s 1970 decision to order Pasadena Unified School District to desegregate its schools was the first federal case of its kind on the West Coast, and one of the few outside the Deep South. Real’s decision came two years after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and as the civil rights movement in America was reaching a boil. At the time, Pasadena was deeply segregated along racial and economic lines, and the city’s schools reflected that.

The busing plan was met with protests, and enrollment in the school district, which then included schools in Altadena and other unincorporated communities, plunged as parents steered their children to private schools or other districts, according to reports in the Los Angeles Times.

With time, however, enrollment bounced back and Real’s ruling was hailed by many as a forward-looking decision.

In a 2016 interview with the Daily Journal, Real reflected on the ruling: “I certainly lost a lot of friends as a result of that decision, but it had to be done.”

Real was among the first district judges appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1966, the same year that the Central District was first established, and was the longest-serving district judge before taking senior status, a form of semiretirement, in November.

Both loved and loathed in the courtroom, Real was sometimes criticized for the way he treated defendants, yet praised for his rulings.

Real also kept an eye on the Trump administration’s immigration and anti-sanctuary cities policies. In February, Real barred Trump from requiring local law enforcement to cooperate with federal immigration officials in order to qualify for anti-gang money.

At the time, Real said in his ruling that the conditions “upset the constitutional balance between state and federal power by requiring state and local law enforcement to partner with federal authorities.”

The previous year, the judge ruled that the Trump administration’s use of similar conditions for community policing was unlawful.

But throughout his career, Real became known for recurrent reversals by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. Judge Stephen R. Reinhardt, who died last year, said at a 2016 event honoring Real’s half-century on the district court that they had some issues with Real on the circuit.

“Judges these days, they go along to get along. Not Manny. He continued to do whatever he felt right.”

Real also was the target of much scrutiny from critics who complained about his court conduct and domineering behavior.

In one such case in 2009, Real ordered the arrest of attorney Gary Dubin in a Honolulu hospital.

Dubin, who was sedated and deeply depressed after the death of his son, was handcuffed and taken to court still wearing his hospital gown to face charges of failing to file tax returns.

Still medicated, Dubin was forced to defend himself without his case files because Real would not reschedule the hearing. After a two-day bench trial, Real deemed Dubin guilty and the attorney spent more than a year and a half in federal prison, during which his house fell into foreclosure and his credit was ruined. In a letter years later, the IRS said Dubin had not violated any tax-filing laws.

His reputation as a tough judge — who decided his cases quickly — inspired his critics to denounce him as a judicial tyrant.

Victor Sherman, an attorney who clashed with the judge often, said in 1985 that Real had “no judicial temperament. … The appearance of justice is just as important as justice itself. In Real’s court, lawyers and defendants leave with a feeling that the whole system is capricious.”

But Real was unaffected by the criticism. “I don’t view my job as somehow having to satisfy the feelings of somebody I’m sentencing,” he said at the time. “I didn’t take this job as a popularity contest.”

Even then, many who knew Real said he was patient and gracious outside the courtroom.

Real was born in San Pedro to immigrants from Spain. His father was a neighborhood grocer.

As a student at San Pedro High School, Real wanted to be an actor, but that changed with World War II. He worked in a San Pedro shipyard for a year and then served in the Navy. In 1944, he received his bachelor’s from USC and graduated from Loyola Law School in 1951.

He then became an assistant U.S. attorney in Los Angeles, and after four years as a prosecutor, he spent the next 10 years doing private practice in San Pedro with his older brother, John, a lawyer who later became president of the StarKist tuna company.

In 1966, two years after serving as U.S. attorney in Los Angeles, President Johnson nominated Real as a judge for the Central District that September. He was confirmed by the Senate the following month and earned his commission in November.

After learning of his death, Circuit Judge Milan D. Smith told the Daily Journal that Real “was an enigma. In private or in social settings, he was the most gracious and genuinely nice person you could meet. Yet in the courtroom, many lawyers were in enormous fear of him. He had no qualms about ignoring what we told him to do.”

“Judge Real has been the heart and soul of our district since it was formed in 1966, and his passing leaves an unfillable void for us, his family, the legal world and the larger community,” Chief Judge Virginia A. Phillips said in a statement. “His legacy of public service is an inspiration beyond compare.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.