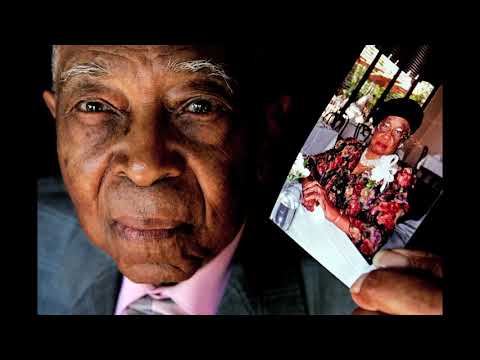

Lee Wesley Gibson, believed to be oldest surviving Pullman porter, dies at 106

Lee Wesley Gibson, believed to have been the oldest living Pullman porter, died as he lived — calm, quiet and in control — sitting in a chair at home Saturday with family members at his side.

Gibson was 106 years old.

For the record:

4:35 p.m. June 29, 2016A previous version of this article said Lee Gibson died Friday. He died Saturday, June 25.

“He had just celebrated his birthday five weeks earlier and he thanked everyone,” said family friend Rosalind Stevenson.

Gibson began work as a coach attendant with Union Pacific Railroad in 1936 at the height of the Great Depression. He was later promoted to Pullman porter, one of the uniformed railway men who served first-class passengers traveling in luxurious sleeping cars. It was a much-coveted job that improved the fortunes of many struggling African Americans at the time.

During a 38-year career, Gibson traveled the country, rubbing shoulders with celebrities and taking pride in the role, though it involved long hours and occasional indignities. Porters were required to respond to the name “George” after the founder of the Pullman Palace Car Co., George Pullman.

“It was hard, but it was fun,” Gibson told The Times in a 2010 interview.

Porter’s 38-year rail job lifted his family into the middle class.

He said the job helped him to “feed my family ... take care of them.”

Gibson purchased a brand-new family home in 1945 in South Los Angeles, and lived in it until his death.

The second child of West Gibson and Annie (Pugh) Gibson, Gibson was born May 21, 1910, in Keatchie, La. After his parents separated, his mother moved with the children to Marshall, Texas, where Gibson attended New Town Elementary School and Central High School, family members said.

When Gibson graduated from high school, he wanted to enroll in tailoring school, but the family couldn’t afford it. Instead, as a teenager his first job was working at Wiley College and Darco Corp., which made chemical cleaners for dry cleaning. He later worked as a presser at Moon’s Cleaners, and eventually bought the business.

In 1927, he married Beatrice Woods, his wife of 76 years. The couple had four children. Lee Jr., Gwendolyn and Barbara were born in Texas. Gloria arrived after the family moved to Los Angeles in 1935 in search of a better life. (Lee Jr. died in 1958 of Hodgkin’s disease. Beatrice died in 2004.)

Gibson initially earned his keep in L.A. making sandwiches at a tavern and doing cleaning for a food production company, he told The Times in 2010.

One day in 1936, a deacon at his church who worked for the Union Pacific Railroad as a coach attendant asked Gibson’s wife, Beatrice, if her husband would be interested in a job with the railroad. It was a golden opportunity, Gibson recalled in his interview with The Times.

The Pullman Co. ended operation of sleeping cars in 1968 and Pullman porters were transferred to Union Pacific and Amtrak. Gibson retired from the railroad in 1974, but kept working.

He served as a volunteer, assisting travelers at Los Angeles International Airport; managed income tax preparation offices for H&R Block; and was district director for the AARP tax preparation assistance program for seniors, family and friends said. Most recently, Gibson was featured in a TV commercial for Dodge entitled “Wisdom,” which honored centenarians, Stevenson said.

He was a devoted member of the 100-year-old People’s Independent Church in Los Angeles’ Hyde Park neighborhood for 77 years, and attended the Sunday before he died.

He raised his family in the church. He is etched in the framework and fabric of the history of the church.

— Bishop Craig Worsham, pastor of the historic house of worship

“He raised his family in the church,” said Bishop Craig Worsham, pastor of the historic house of worship. “He is etched in the framework and fabric of the history of the church.”

Gibson served as church treasurer, deacon, elder and an officer of the church credit union, Worsham said.

“He was a very polite gentleman, very encouraging of the work of the community,” Worsham said. “He had a pleasant spirit, he was gentle, and he excelled at being a father, grandfather and great-grandfather.”

Gwendolyn Reed, 84, Gibson’s eldest daughter, said her father doted on her and her sisters, Barbara Leverette, 82, and Gloria Gibson, 71.

When they were girls, the porter would utilize his sewing skills and tailored outfits for his daughters, including their flag girl uniforms. A couple of years ago, Gibson offered to hem a skirt that Reed wanted shortened, she recalled. He started the job, and when Reed finally insisted on taking the skirt to the dry cleaners to finish the job, the attendant marveled at Gibson’s seamstry, Reed recalled.

Known for his immaculate clothes — he often sported designer suits and custom-made dress shirts — Gibson credited his longevity to keeping things simple. He took only a daily vitamin until the day he died, family members said.

Into his 100s, he was fit and alert, taking no medication, seeing without glasses and still driving, until the family insisted he stop at age 102.

“He was such an inspiration,” Stevenson said. “He was a man who truly loved his family and his God. It was just the simplest way to live and he did so successfully.”

Over the years, Gibson received letters congratulating him on his longevity from President Obama, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, Los Angeles County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, and former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. He served as grand marshal for the Watts Christmas Parade in 2010.

“He was a man whose outlook on life was extremely positive,” Reed said. “He didn’t believe in the word ‘can’t.’”

In addition to his three daughters, Gibson is survived by six grandchildren, 18 great-grandchildren, 22 great-great-grandchildren, and three great-great-great-grandchildren.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.