Van Johnson, MGM’s boy-next-door, dies at 92

Van Johnson, who soared to stardom during World War II as MGM’s boy-next-door in films such as “A Guy Named Joe” and “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo” and became one of the era’s top box-office draws, died Friday. He was 92.

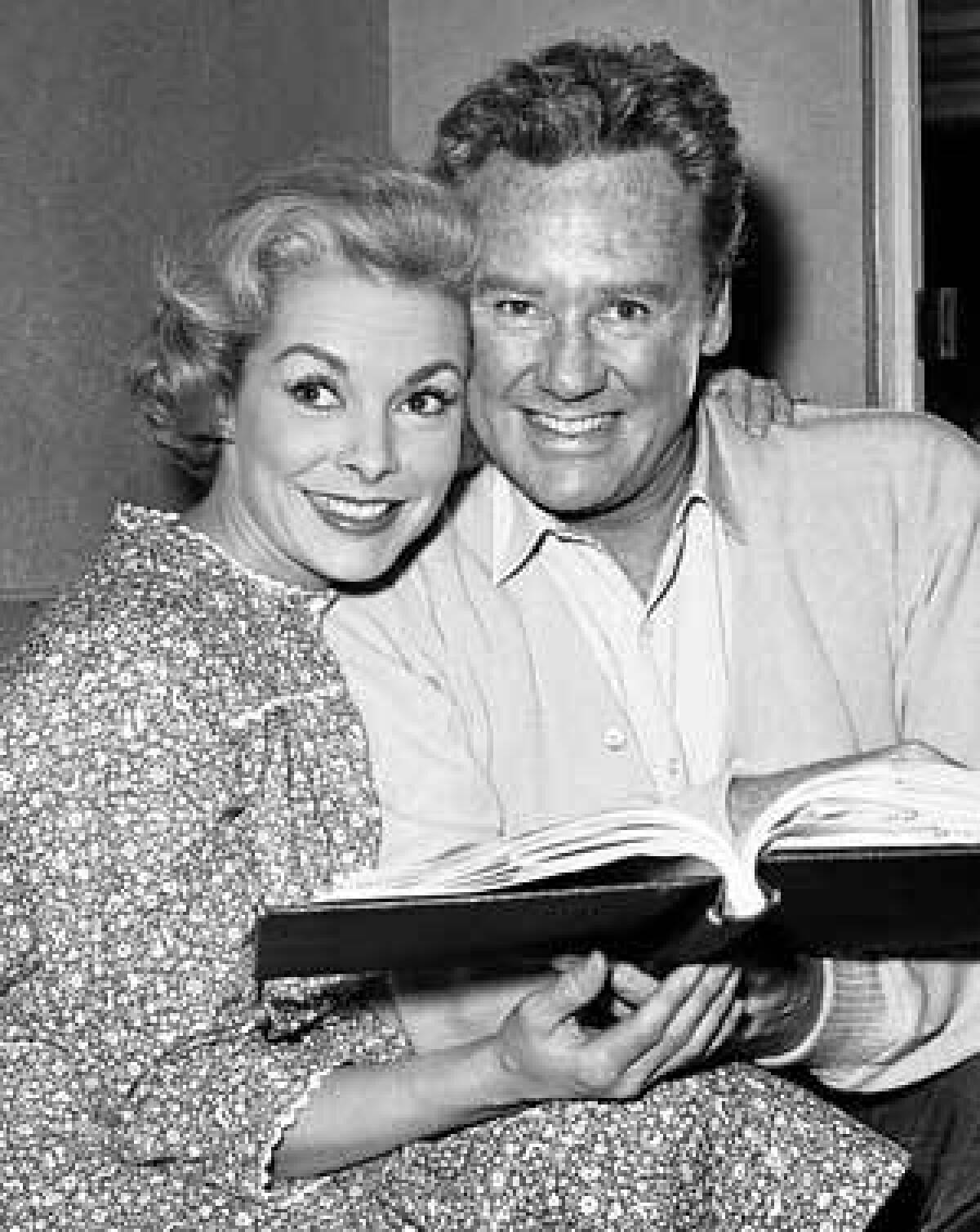

Johnson, who was most frequently cast opposite June Allyson and Esther Williams during his MGM heyday, died of age-related causes at a senior residence in Nyack, N.Y., said Wendy Bleiweiss, a close friend.

With his broad smile, red hair and freckled face, the tall onetime Broadway chorus boy personified the wholesome young American man, MGM-style.

“A Guy Named Joe,” the 1943 fantasy romantic-drama starring Spencer Tracy as a World War II pilot who is killed in action and returns to earth in spirit form to help novice pilots, provided a breakout, critically acclaimed role for Johnson: He played a young pilot who falls in love with Tracy’s girlfriend (played by Irene Dunne).

Johnson had become an MGM contract player only a year earlier, but his road to stardom nearly ended before he ever got in front of the cameras for “A Guy Named Joe.”

While he was driving to a screening at MGM with friends in March 1943, a car ran a red light at a Culver City intersection near the studio and smashed into the side of Johnson’s convertible, causing it to roll on its side.

With a fractured skull, severe facial injuries, a severed artery in his neck and bone fragments piercing his brain, Johnson underwent several surgeries. He was left with a severely scarred forehead and ametal plate on the left side of his head, which exempted him from military service.

But his near-fatal accident and three-month hospital stay provided the kind of publicity that not even MGM could buy: The fan magazines ate it up. And his 4-F status allowed him to continue his fledgling movie career at a time when many Hollywood stars were in uniform.

For his part, Johnson fought World War II on the big screen, the wardrobe department providing him with a constant change of GI garb.

Among other films of the period in which he played a serviceman are “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo” (1944), “Two Girls and a Sailor” (also 1944, and the first time he received top billing) and “Week-End at the Waldorf” (1945).

By war’s end, he’d later joke, “I’d been in every branch of the service, all at MGM.”

By the end of 1945, Johnson also had joined the ranks of the top 10 box-office stars for the first time, placing second (behind Bing Crosby) in the annual exhibitors’ poll.

So great was Johnson’s bobby-soxer following that the Hollywood columnists dubbed him “The Voiceless Sinatra.”

“He handled it very well,” Esther Williams told The Times in 2003. “He was probably one of the most charming, gregarious of the stars I worked with.

“If you look at any of his pictures, look at ‘Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo.’ You’ll see why he was a big star, because he had this wonderful, boyish quality with those freckles and that smile. He was so natural.”

June Allyson summed up the actor’s screen appeal this way: “He was very, very down-to-earth,” she told The Times in 2003. “I think he was the man every girl would like to marry. I just loved working with him. He was delightful, he was funny, and he was always prepared.”

Johnson’s high-flying popularity, however, was short-lived.

By 1946, he had fallen only slightly in ranking at the box office -- from second to third place -- but it was the last time he made the top 10 list.

In January 1947, Johnson married Eve Wynn, the former wife of his close friend, actor Keenan Wynn. Johnson married Wynn, the mother of two young sons, in Juarez, Mexico, only four hours after she had obtained a Mexican divorce. (The marriage, which produced a daughter, Schuyler, ended in divorce in 1968.)

Johnson’s marriage had a profound effect on his youthful female fan base. A widely circulated joke at the time said that when Johnson’s young female fans found out that he had gotten married, they wore their bobby socks at half-mast.

And fan magazines, which had previously written glowing articles about MGM’s golden boy, insinuated that the marriage to a woman who had been his best friend’s wife harmed Johnson’s career.

Although his popularity diminished, Johnson continued working steadily.

Between 1947 and 1954, he had co-starring and supporting roles in more than two dozen films, including “State of the Union,” “In the Good Old Summertime,” “Command Decision,” “Battleground,” “Brigadoon,” “The Last Time I Saw Paris” and “The Caine Mutiny.”

In 1954, after 12 years at MGM, he became a freelance actor.

Along the way, he had spent weekends at William Randolph Hearst’s San Simeon estate, shared gossip with Marlene Dietrich, painted with Henry Fonda, partied with Errol Flynn, gone on walks with Greta Garbo, lunched with the Duchess of Windsor and cruised on Aristotle Onassis’ yacht with Winston Churchill.

“I’m the luckiest guy in the world,” Johnson said in a 1997 interview. “All my dreams came true. I was in a wonderful business, and I met great people all over the world.”

He was born Charles Van Dell Johnson on Aug. 25, 1916, in Newport, R.I. His Swedish-born father was a plumber whose marriage to Johnson’s alcoholic mother ended when she walked out of their home in a boarding house when Johnson was 3.

Johnson, an only child, was raised by his humorless father and, until her death when he was 12, his paternal grandmother.

Growing up, Johnson studied singing, dancing and the violin -- and fell in love with show business. Intent on finding work singing or dancing after graduating from high school in 1934, he moved to New York City a year later.

By mid-1936, he was appearing in the chorus of the Broadway musical-revue “New Faces of 1936.”

A succession of other show-business jobs followed, including being a member of the chorus and the understudy for the three male leads in the 1939-40 Broadway production of the Rodgers and Hart musical “Too Many Girls.”

In 1940, he made his unbilled screen debut as a chorus boy in the Hollywood version of “Too Many Girls.” Later that year, he was hired for Rodgers and Hart’s new Broadway musical “Pal Joey,” in which Johnson sang a song, danced in the chorus and had some lines.

In late 1941, Johnson signed a six-month contract with Warner Bros. But after playing the leading role in only one movie -- as a cub reporter in the low-budget “Murder in the Big House” -- he was dropped by the studio.

Figuring he was “washed up” in Hollywood, Johnson planned to return to New York. But when his friends Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz learned he was leaving, they invited him to dinner at Chasen’s restaurant to say goodbye.

And as luck would have it, the person sitting at the next table was Billy Grady, head of talent at MGM, which had just signed Ball. She took Johnson over to Grady, pleading for him to keep Johnson in Hollywood.

The upshot: Grady invited the boyishly personable Johnson to do a screen test at MGM, which wound up signing him to a $350-a-week contract.

During his early months in Hollywood, Johnson began sporting what became his off-screen trademark: red socks.

Three years after leaving MGM in 1954, Johnson’s film career began to wind down. Among his later film credits: “Kelly and Me” (1957), “Wives and Lovers” (1963), “Divorce American Style” (1967), “Yours, Mine and Ours” (1968) and “The Purple Rose of Cairo” (1985).

In 1961, Johnson returned to the stage, starring in the title role of the London production of “The Music Man.” In 1962, he returned to Broadway, appearing opposite Carroll Baker in the drama “Come on Strong.”

Throughout the 1970s and ‘80s, he performed in regional and dinner-theater productions.

Over the years, Johnson also made occasional TV guest appearances, and he earned an Emmy nomination for his supporting role in the 1976 miniseries “Rich Man, Poor Man.”

A list of survivors was not immediately available.

McLellan is a Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.