Filmmaker John Singleton dies; ‘Boyz n the Hood’ was his own personal L.A. story

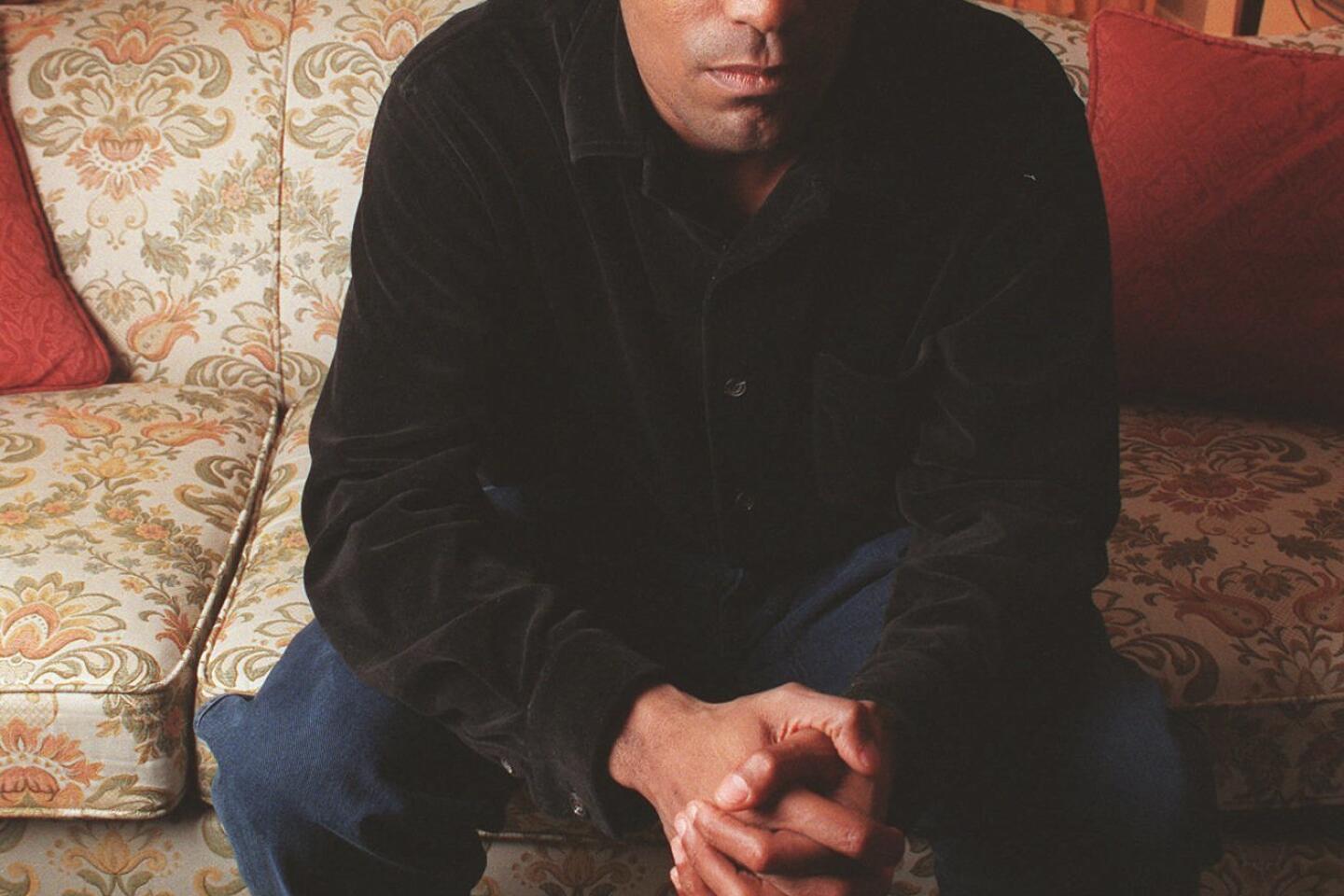

With his 1991 drama “Boyz N the Hood,” director John Singleton became the first African American filmmaker nominated for a directing Oscar. He died following complications from a massive stroke he suffered on April 17.

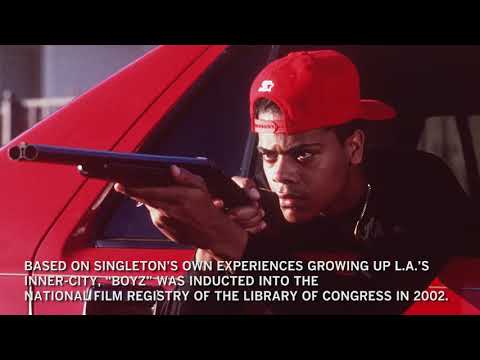

The streets of South L.A. were marked and divided by gang warfare when “Boyz n the Hood” arrived in America’s movie houses, a violent and profane yet somehow deeply sentimental look inward for a troubled city.

A coming-of-age story amid the destructive cross-currents of inner city life, the film marked the debut of a brash 24-year-old filmmaker, who’d polished off the script in just three and a half weeks during his senior year at USC. In every sense, it was his story, his neighborhood.

The 1991 film, nominated for two Academy Awards, pulled John Singleton into the company of emerging black moviemakers such as Spike Lee, Mario Van Peebles and Matty Rich. Relevant and thoughtful, Singleton remained prolific over the decades.

On Monday, 13 days after suffering a stroke, Singleton died after being removed from life support. He was 51. In a statement, his family said Singleton — like many African Americans — suffered from hypertension.

“John didn’t just make his feature film debut in 1991 with ‘Boyz n the Hood,’ he exploded into Hollywood, our culture and our consciousness with such a powerful cinematic depiction of life in the inner city,” said director and producer Thomas Schlamme.

Singleton’s family described him as a “supernova” as a child, a bundle of curiosity who found inspiration and role models in one of L.A.’s toughest neighborhoods.

He was just 24 when he directed “Boyz n the Hood,” becoming the youngest person to be nominated for an Academy Award in that category. The film, a harrowing tale of childhood, friendship and peril in South L.A., was based on Singleton’s own experiences and was also nominated in the original screenplay category.

The son of a mortgage broker father and a pharmaceutical company sales executive mother, Singleton was raised in separate households by his unmarried parents.

“My life changed when I went to school in the Valley, when I was in eighth grade,” he told The Times in 2017. “It was the first time I went on the 405 Freeway. They were rich in Encino, Tarzana. You see a different life. Everyone was changed by the crack problem in my neighborhood. I remember ice cream trucks and you realize the ice cream truck isn’t selling ice cream, they’re selling crack.”

Born Jan. 6, 1968, John Daniel Singleton grew up in South L.A. While only miles from Hollywood, his neighborhood might as well have been a world away from the studios and back lots.

His modest upbringing shaped his work, including his debut film, “Boyz n the Hood.” After graduating from Pasadena’s Blair High School in 1986, he attended USC’s film school where he landed an internship at Paramount and won three awards, leading to a contract with Creative Artists Agency during his sophomore year.

Elizabeth Daley, dean of USC’s School of Cinematic Arts, said Singleton was known to the professors there before he was even a student, roaming the hallways, sitting in on classes and engaging professors about their favorite films.

“He bulldozed his way into an industry that was not always welcoming, and did so with projects that reflected his community, his culture and his passions.” Daley said. “He is a giant in our hearts.”

Though Singleton’s only student film experience was directing a pair of silent 8-millimeter movies, his film school scripts were impressive, earning him the Jack Nicholson writing award two years in a row.

He wrote the script for “Boyz n the Hood” in just three and a half weeks and presented it as his senior thesis, and it was quickly snatched up by Columbia Pictures. Despite his inexperience, Singleton insisted that the only person who could possibly do justice to the film was himself. After a lengthy meeting on the studio’s lot, he earned a powerful ally in the studio’s chief, Frank Price.

“I thought John’s script had a distinctive voice and great insight,” Price told The Times in 1991. “But when we met, I was really impressed. He’s not just a good writer, but he has enormous self-confidence and assurance. In fact, the last time I’d met someone that young with so much self-assurance was Steven Spielberg.”

The movie, filmed for a mere $5.7 million, became the first all-black movie about L.A.’s inner-city struggles to be produced by a major studio and was inducted into the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress in 2001. When it screened at the Cannes Film Festival, the audience gave it a 20-minute standing ovation.

“Boyz n the Hood” arrived at the theaters as the L.A. gang wars were escalating and just nine months before the Rodney King beating and the deadly street riots that engulfed the city.

“When ‘Boyz n the Hood’ came out, it became part of this small uprising” in black cinema, USC professor and student of African American cinema Christine Acham said in 2011. “It had really been squashed since the early ’70s. To see these black films come to the forefront was something that was pretty significant. Instead of being represented, you have a case of people trying to represent themselves.”

The film went on to earn two Oscar nominations — best screenplay and best director, earning more than $60 million at the box office.

Following “Boyz n the Hood,” Singleton went on to direct “Poetic Justice” (1993) starring Tupac Shakur and Janet Jackson, “Higher Learning” (1995) and “Baby Boy” (2001), which featured Taraji P. Henson at the start of her career.

“This movie is like watching the soul of a black man on screen,” Singleton said of the latter film in a 2001 interview with The Times. “It may be dysfunctional, but it’s real.”

In those films and in later works, Singleton continued to explore the implications of inner city violence.

He directed, produced and wrote the screenplay for the remake of “Shaft” (2000), directed “2 Fast 2 Furious” (2003) and “Four Brothers” (2005), and produced “Hustle & Flow” (2005) and “Black Snake Moan” (2006).

In a departure from his film credits, Singleton directed the visual effects-heavy music video for Michael Jackson’s “Remember The Time,” which featured Eddie Murphy, the model Iman and Magic Johnson. His 1997 historical drama “Rosewood,” which explored racial violence, was entered into the 47th Berlin International Film Festival.

Singleton was passionate about increasing diversity in the film industry, embracing and working alongside Regina King, Tupac Shakur and Ice Cube.

“I want to do for the movie business what Jay-Z did in the music business,” he told The Times in 2006. “He’s the guy everyone goes to for guidance, which is a role I want to embrace, being a godfather to a new generation of filmmakers. I want to nurture the next generation, which is where our future will come from. I’m hoping I can give them what I always wanted, which is some real-life advice.”

In 2007, Singleton was involved in a car accident in Los Angeles where he struck and killed a pedestrian who was jaywalking. He was detained for questioning, but no charges were filed.

In 2017, Singleton produced the A&E documentary “L.A. Burning: The Riots 25 Years Later.” Most recently, he co-created and produced the FX series “Snowfall,” about the rise of the crack epidemic in 1980s Los Angeles.

“I don’t think I could ever have accomplished what I have if I started now,” he told The Times in 2017. “How do you break through the clutter, man? What everyone wants is to get their voice heard and by as many people as possible. But how do you quantify that in this world? I don’t know, I don’t know. It’s not for me.”

He also directed episodes of “Empire,” “Billions” and “The People vs. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story” and launched the BET police drama “Rebel,” which he wrote, directed and produced.

“I have a whole lot of stories to tell,” he explained in 2017. “With television, I’m like making a movie every week. What filmmaker doesn’t want to have the opportunity to do that?”

He is survived by his mother, Sheila Ward; his father, Danny; and children Justice, Maasai, Hadar, Cleopatra, Selenesol, Isis and Seven.

Twitter: @sonaiyak

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.